BOOK REVIEWS

The Transformation of Professional Values in Chinese Investigative Journalism

Alain Peter teaches at the School of Journalism (Centre Universitaire d’Enseignement du Journalisme – CUEJ), University of Strasbourg. CUEJ, Bâtiment l’Escarpe, 4 rue Blaise Pascal, CS 90032, 67081 Strasbourg Cedex, France (alain.peter@cuej.unistra.fr).

The early 2010s saw sweeping changes in the Chinese news media ecosystem. First, the economic model underpinning the growth of traditional media – including print – collapsed. Audience figures dropped and so did ad revenues. Commercial media outlets that emerged in the 1990s and 2000s had experienced boom years thanks to a strong increase in circulation and advertising revenue, but that slowed down (Zhao 2008). As a result, by 2012, the growth of the advertising market for traditional media (print, radio, TV) was only 4.5%, its lowest level in five years.[1] This average masked significant disparities: the advertising revenues of radio and television companies were still up by respectively 8.9% and 6.4% in 2012, whereas those of daily newspapers had dropped by 12.6%. The struggles of the traditional media were a result of the rise of online media, which began hogging audiences and ad revenues. In 2012, advertising revenue for online publications was up by 46.8%; two-figure growth rates were maintained during the entire decade.

Second, Xi Jinping’s 習近平 accession to power heralded an authoritarian takeover of news media companies and internet publications (Repnikova 2017a; Guan 2020; Strittmatter 2021).[2] As soon as he was inducted as the head of the Chinese Communist Party and of the state in 2012-2013, the country’s new strongman asserted his intention to “occupy the commanding heights of information and communication” by creating “a line of strong online armies,” arguing that “the Internet has become the main battlefield for the public opinion struggle (yulun douzheng 輿論鬥爭).”[3] On the occasion of visits to the editorial teams of three state-owned media outlets, on 19 February 2016, he announced that “the media run by the Party and the government are the propaganda fronts and must have the Party as their family name (bixu xing dang 必須姓黨).”[4] Submission to the Communist Party was naturally expected from all the official media outlets visited by Xi Jinping, but also from their commercial counterparts and the new media. All media outlets “must adhere to the correct guidance of public opinion (zhengque yulun daoxiang 正確輿論導向). The Party’s newspapers, radio stations, and television channels at all levels must receive guidance, just as the metropolitan papers and the new media outlets must also receive guidance,” he stressed.

These sweeping transformations on the media ecosystem have resulted in a 25% drop in the number of card-carrying journalists between 2014 and 2022.[5] They also affect investigative journalism, which has not disappeared altogether, but has been experiencing a decline that is reflected by several indicators. Faced with dwindling financial resources and tightened censorship, the commercial media are less often able to conduct investigations that question national Communist Party policies in the same way as earlier reports on Sun Zhigang’s 孫志剛death in a detention centre (2003),65 the pollution of the Songhua River (2005),7 or the earthquake in Sichuan (2008).8 These examples illustrate the eagerness of investigative journalists in the 2000s to critically question the actions of the national authorities in the name of the right to “supervision by public opinion” (yulun jiandu 輿論監督) initially introduced by the Communist Party to control the actions of civil servants, in practice mainly at the local level of the administration.9 Even though sensitive political subjects have always remained off-limits, these opportunities led to the birth of a Chinese form of investigative journalism, which was ostensibly aimed at informing the public and asserted a modicum of independence from the authorities. However, since 2013, the state has emphasised the need to perform “constructive supervision” (jianshexing jiandu 建設性監督). This is not new terminology per se, but the emphasis on that aspect during the Xi Jinping era leaves much less room for criticism. A second sign of decline is the decreasing number of investigative journalists – from 334 to 130 between 2010 and 2016 according to a study by researchers from Guangzhou’s Sun Yat-sen University.10 In fact, many experienced reporters did end their careers in the field in the 2010s; some joined internet or communication companies, other charities.

Yet, the editorial teams of some commercial media outlets still have investigative journalists on the payroll who attempt to reveal hidden truths to the public. New media outlets with openly stated investigative ambitions have been launched, such as The Paper (Pengpai 澎湃) app (Peter 2019). It remains to be determined whether the professional values of these journalists, meaning the principles and standards underlying their work, have remained identical or have changed. Of particular interest, for instance, is establishing whether or not the junior investigative journalists that began their careers after 2010 share with their colleagues who started in the 1990s and 2000s the same definition of investigation and of their social role. If changes are noticeable, are they attributable solely to the changes in the news media system, or are other factors involved?

Age differences between investigative journalists could be ignored in the 1990s and 2000s, when editorial teams were made up of junior reporters whose supervisors were in their thirties. For instance, Cheng Yizhong 程益中, the editor-in-chief of Southern Daily (Nanfang dushibao 南方都市報), was 38 years old in 2003, at the time of the Sun Zhigang affair, when he backed the work done by journalists Wang Lei 王雷 and Chen Feng 陳峰, then respectively aged 27 and 31. As most belonged roughly to the same age group, the community of investigative journalists was particularly tight-knit. Since the 2010s, age gaps between junior and senior reporters have widened. For instance, as of 2018, at Chinese Youth Daily (Zhongguo qingnianbao 中國青年報), Liu Wanyong 劉萬永, aged 47, supervised journalists who were 20 years younger.

The rise of Chinese investigative journalism in the 1990s and the 2000s has been abundantly documented. The major books on the subject have respectively given detailed accounts of landmark investigations (Bandurski and Hala 2010), analysed the tactics used by reporters and their role in environmental discourse (Tong 2011, 2015), discussed the relationships between investigative journalists and an authoritarian regime (Stockmann 2013), examined the values of investigative journalists (Svensson, Sæther, and Zhang 2013) and the ways in which they contribute to changing China (Hassid 2016), observed that some of the best specialists have exited the field (Wang 2016), and illuminated the dynamic ambiguity at the heart of the relationships between the authorities and the journalists (Repnikova 2017a). Under the categorisation of investigative journalists proposed by Jonathan Hassid (2011), the journalists discussed in this study are “advocacy professionals.”11 The nature of Chinese-style investigative journalism has been subject to much debate. Is it merely an instrument in the service of power considering that “Chinese media watchdogs are not only on the Party’s leashes but are also wearing an indisputable official jacket,” as Zhao Yuezhi (2000) reminds us? Or should our conclusion be that the reform of information has provoked a chaos “that cannot be described in black and white” as Qian Gang argues?12

On the other hand, the study of investigative journalists from a generational perspective is in its infancy. Bai Hongyi (2013) has noted that junior journalists are more attached to the idea of objectivity than their senior colleagues, and explained this by the need for them to protect themselves from accusations of bias at a time when the authorities have ramped up control over editorial boards.

Wang Haiyan’s recent study is the first in-depth analysis on the subject. Drawing on the work of German sociologist Karl Mannheim, who argued that a generation is defined less by the age of its members than by the experience of a shared history and of the same events, she has found that “young people entering journalism today confront different circumstances and their resultant views, as well as their journalistic activities, are significantly different, and less engaged, than those of their seniors.” (2021: 104) She observes that “the successful kinds of journalism today are not those that expose the very real social problems of contemporary Chinese society, which are just as pressing today as they were twenty years ago.” (ibid.: 122) Wang Haiyan explains this change by the transformations of the news media ecosystem in the early 2010s, and by the fact that “the younger generation of journalists are from more privileged backgrounds” (ibid.: 122), having grown up in a China in which “economic prosperity is no longer a novelty: for many, a degree of family wealth has become familiar and social inequality is perceived as a natural fact of life.” (ibid.: 114) This, she claims, make the young generation of journalists “passive,” compared to their “active” elders.

Based on the idea that a generation is defined by a combination of natural characteristics and shared social experiences, this article is intended as an extension of this effort to analyse Chinese investigative journalists from a generational angle. Its findings support those of Wang Haiyan and bring new elements to the interpretation of the differences between the two generations of journalists – the over 35 and the under 35. Setting the boundary at age 35 to distinguish the two generations is partly an arbitrary decision. The trends identified here would be basically the same had we set the limit at age 34 or 36 – only one journalist was aged precisely 35. However, that age has the advantage of echoing an observation made by media executives, who told me that they struggled to retain journalists “in their mid-thirties” in their staff.

The over 35 started between the late 1990s and the early 2000s, whereas the under 35 joined editorial teams after 2010. These two groups have come of age in very different economic and political environments that have shaped their historical experiences and professional practices. The first generation lived through China’s years of great economic growth and opening up to the world; it contributed to the marketisation of the media in the 1990s and to the emergence of investigative journalism. The second group entered the labour market as economic growth was slowing down and digital media were making inroads to the detriment of traditional outlets, and at a time when Xi Jinping restricted the freedom of investigative journalists to work.

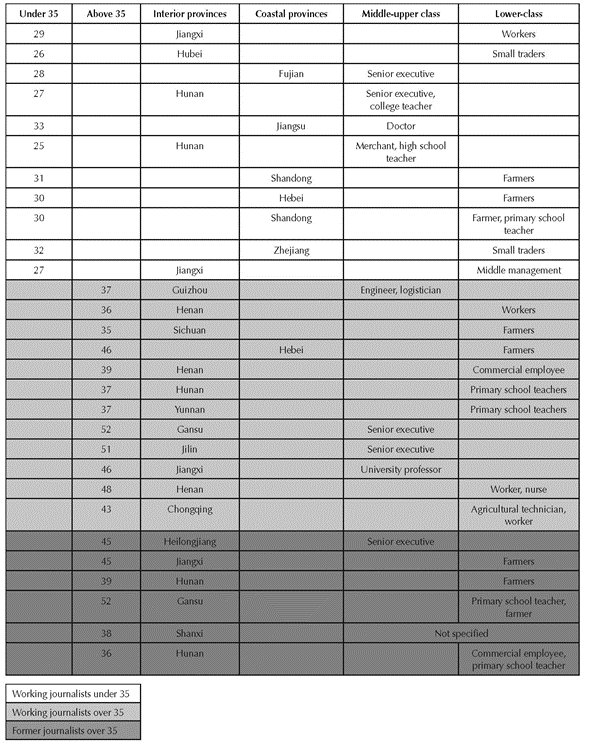

This study draws on semi-structured interviews conducted between 25 October 2016 and 19 November 2019 with 29 current and former investigative journalists in Guangzhou (eight), Beijing (16), Shanghai (four), and Shenzhen (one). This panel comprises 25 men and four women, divided into three subgroups: 11 were aged under 35 and worked as journalists at the time of the interview; 12 were over 35 and worked as journalists at the time of the interview; six were over 35 and no longer worked as journalists at the time of the interview. These individuals are or were investigative journalists in the main media outlets known for their forays in that genre: Nanfang dushibao, Zhongguo qingnianbao, News Probe (Xinwen diaocha 新聞調查) etc. Perhaps as a result of my own connections, print and online journalists are strongly overrepresented (27 out of 29). It should, however, be noted that four TV and radio journalists turned down my interview requests.

Interviews were conducted in Chinese (except for one in English and another in French), face-to-face; participants were assured they would remain anonymous. Most took 30 to 45 minutes; the shortest was 20 minutes, and the longest 80 minutes. They were recorded with the agreement of the interviewees and transcribed into French by a professional translator. The names of the interviewees were coded using a single letter.

Interviewees were selected in three ways: through recommendations by other journalists I met during the course of the study (13), recommendations by lecturers specialising in investigative journalism at Chinese universities in Guangzhou and Shanghai (12), and some of my own personal contacts during previous studies (four). Biographical data (age, training, geographic origin, parents’ occupations) were collected (see Table 1). Interviewees were asked questions designed to have them expand on their interest in investigation, their definition of investigation, their views on their relationship to the public and to the authorities, and their assessment of the current state of the news media.

Table 1. Age, geographical and socioeconomic origin of the interviewees

Source: author.

Twenty-nine interviews is too small a corpus to allow for statistical processing, and this calls for caution when drawing general conclusions. It does, however, permit qualitative analysis and the identification of general trends (Thomson 2011). The 23 interviewees who were active as investigative journalists at the time of the interviews made up 18% of the 130 members of this professional community in 2016, according to Sun Yat-sen University.

This article begins by observing differences in the professional values cited by the two generations of journalists who report a transformation. Then, it shows that these differences are correlated with changes in the academic training and social backgrounds of the two generations of journalists. In conclusion, the political implications of these findings are discussed.

A transformation of professional values

As all Chinese media are controlled by the Communist Party, none of the investigative journalists I interviewed cited independence from power as a core professional value, as their colleagues working in democratic countries would have done. On the other hand, Chinese journalists emphasise three essential values. The first consists in revealing misdeeds: “Investigative journalism is about revealing hidden misdeeds, things that were not spontaneously made public, that do not come from a press conference or a spokesperson,” says G. (interview in Guangzhou, 26 November 2018, age 33). The second value is being in the service of public interest: “The starting point is the defence of the public interest and of citizen’s rights,” as R. puts it (interview in Beijing, 23 August 2017, age 52). The third is reporting the facts accurately: “It’s the most important thing, because facts help the public know the truth,” according to V. (interview in Beijing, 18 November 2018, age 51).

While they unanimously assert these three values, the two generations of journalists differ in the ways in which they put them into practice, regarding the freedom to choose topics, the scope of their investigations, and their relationship to power.

The freedom to choose topics

The most noticeable divergence in the interviewees’ responses concerns the freedom to choose topics to cover, and revolves around the idea of the journalists’ “professional responsibility” (zhiye zeren 職業責任). Those aged under 35 more frequently mention it as a reason not to address sensitive subjects, whereas the over 35 tend to condemn what they perceive as a form of self-censorship.

This difference does not emerge immediately, but only when interviewees are called to elaborate on how they choose subjects they deem worthy of investigating. Indeed, as long as professional responsibility is conceived in ethical terms, it is a concern for both generations. Z.A., a 29-year-old man, says: “You just have to avoid doing harm to people when you’re breaking news when it wasn’t the initial intention” (interview in Guangzhou, 26 November 2018). Along the same lines, Z.C., a 43-year-old man, notes that “you don’t go looking for news on the private lives of underage individuals, you don’t overstep your bounds to chase scoops even though there’s a lot to find there” (interview in Guangzhou, 28 November 2018).

Additionally, professional responsibility is invoked by journalists of both generations as a reason not to pursue a sensitive topic. Z.A., for instance, explains his refusal to cover some subjects out of a fear of making them worse: “In a society, there’s always lots of problems. If by trying to resolve small problems you’re creating bigger ones, then that becomes a problem in itself…” He cites the prostitution of African women in China as that kind of topic:

Black men who live in China have to satisfy their sexual needs, since many of them are single or separated from their families. China has a ban on prostitution. But in effect, the Chinese police tolerate the prostitution of African women, and monitor it at the same time. I think it’s a good thing. If I were to investigate this subject to denounce police tolerance of African prostitution, I would effectively risk sparking an increase in crime and sexual violence towards women.

Young journalists are not the only ones to exert self-censorship because they fear they could make a situation worse. According to K., who is 37:

Some subjects should not be covered, for instance those that are too violent, or pornography, or other subjects that can impact public security. By public security, I mean news that you sometimes hear about that relate to state secrets, the army, or changes in the government. Even if I were free to do so, I would not cover these subjects. It has nothing to do with ideology. I think there are state secrets in each country and that they should not be discussed publicly, even if I will grant you that there are more in China. (Interview in Beijing, 23 November 2018)

The very experienced I. also considers that “the media should not cover state secrets, those that pertain to state security. In each journalist’s mind, there’s a ministry of propaganda – in other words, self-censorship. When you’re sent news, you ask yourself: can I cover that or not? But in fact, sometimes you do think too much” (interview in Beijing, 21 November 2018, age 47).

As for V., who is in his fifties, he says, “You can make concessions. I’m not an extreme journalist, asking to investigate all topics. Democracy and religion are powder kegs in China. Even a small incident could make great waves.”

However, only journalists above 35 reject the argument of professional responsibility when it is summoned to justify self-censorship on sensitive issues. To C., for instance:

The journalist’s mission is to report on the current reality. If I believe that a subject has journalistic value, I must investigate. This is why I think journalists have to report on all subjects freely. Some investigative journalists think that their investigations should depend on the political situation, when it comes for instance to revealing cases of corruption among civil servants, as has been the case over the past few years. I am among those who believe that there should be investigations on all major affairs, including environment and science-related ones, to reveal what they are concealing. (Interview in Guangzhou, 12 April 2017, age 35)

L., a 36-year-old, argues: “It’s not up to me to practise censorship, for instance on national security. I can do the piece and they can decide not to publish it. I think as a journalist, you shouldn’t censor yourself” (interview in Beijing, 20 October 2016).

However, in the Chinese context, this rejection of self-censorship has more to do with utopic thinking than actual practice, as 39-year-old H. suggests: “In my view, a journalist should freely report on all subjects. No forbidden topics. Ideally, of course” (interview in Beijing, 27 April 2018). Y., who is 38, argues that a journalist’s professional responsibility should lead them to investigate even when they already know that their work will remain unpublished: “As soon as I started working on a new story, I could assess whether it would be published or not. But even if I knew it wouldn’t be published, I’d do it anyway; at least that way my conscience was clean!” (interview in Beijing, 26 October 2016). The paper for which Y. was working in the 2000s was turning large profits.

The scope of investigation

During the interviews, journalists were asked to describe their best piece of investigation; responses revealed that the older generation’s scope of investigation is more ambitious.

While all the journalists can embrace J.’s assertion that their work aims to “unveil the truth hidden in darkness that the public cannot see, reveal illegal actions by civil servants, by certain organisations or companies,” (interview in Guangzhou, 13 April 2017, age 39), the under 35 tend to mention investigation with a local scope: on injustices suffered by individuals, investigations into accidents, falsifications of documents by local civil servants, etc.

On the other hand, journalists over 35 say that their best investigations are those that involved posted officials, “living tigers,” on the grounds that they are powerful individuals. C., for instance, is particularly proud of his investigation into Zhou Yongkang 周永康, then a member of the Politburo Standing Committee (2007-2012) and a former minister of Public Security (2002-2007): “Publishing a story about Zhou Yongkang meant taking a great risk: one word from him and you could spend your life in prison or die on the road and they would rule it an accident.” Q., for her part, is quite aware that “doing investigative journalism is monitoring public power: the corruption of power, the collusion between power and a variety of interests, the interests generated by the wielding of power” (interview in Beijing, 18 November 2018). Some of her revelations have led to the fall of high-ranking military officers and of the chief of police in a large metropolis.

In other words, the under 35 tend to mention investigation on local stories involving low-level officials, whereas to the over 35 only cases dealing with active officials and national-level matters qualify as investigative journalism.

Relationship with power

When asked to rank whom they work for by order of importance among a number of choices (“for myself,” “for the public,” “for my publication,” “for the government”),13 many journalists struggle to rank these answers in hierarchical order. E. sums up the dilemma: “If I absolutely have to choose, I’ll answer that I’m working for the public. But there is no question of ranking the answers, as I believe that all journalists must work for the public, for themselves, and for their publication, not for the government” (interview in Shanghai, 28 August 2017, age 45).

Despite this apparent unanimity, many journalists over 35 make a point of spontaneously adding that they are ranking the government fourth, but only because they are asked to do so for the purpose of the question. They would rather not have included it at all in the ranking. “I don’t work for the government, so I’m not selecting this answer,” H. decided. “Journalists must work for the public, not for the government,” E. commented.

Conversely, with a single exception, the under 35 agreed to rank the government among the possible answers, if only last. “I also have a responsibility towards the government,” S. grudgingly admitted (interview in Shanghai, 31 October 2019, age 27). B., for his part, accepted ranking the government fourth because “it provided funds for the launch of the publication” in which he is employed (interview in Beijing, 26 April 2018, age 26). “The interests of the public and of the government overlap. Except when the government is bad, it wants society to get better and better, as that way its power will be reinforced too,” according to Z.A. The only journalist who outrightly claims to be working for the government is under 35: F., aged 27, says: “The way I really feel, it’s the government; in China that’s what the job is like” (interview in Shanghai, 28 August 2017).

When asked if they think that investigative journalism is encouraged under Xi Jinping’s leadership, the vast majority of interviewees answer in the negative. On that question too, though, differences between the two generations emerge: out of the four journalists who express optimistic views on the subject, three are under 35. Thirty-year-old X., for instance, sees the existence of contests as an encouraging fact: “I think it’s encouraged. There are contests in which investigative journalists can receive prizes. It’s a recognition and an encouragement to do better. There’s also the sense of honour that comes with investigative journalism” (interview in Guangzhou, 12 April 2017). B. makes a more nuanced point:

Compared to the situation ten or 20 years ago, clearly investigative journalism is less encouraged now. If you do it properly, the government and the public will encourage you. If you do it improperly, you’ll get criticised, of course. The most important thing is to work the right way.

T., who is 31, has conflicted feelings:

Internally, two things are mentioned: (1) doing propaganda for the Communist Party and (2) supervising public opinion. But 1 is mentioned way more often than 2… As for the public, there is an interest in investigation and the genre is closely followed, even though people don’t always have enough patience to read long-form stories. At the governmental level it’s not very popular; they still see us as the workers of Communist Party journalism. Still, overall, in my view, it’s encouraged. (Interview in Beijing, 26 April 2018)

Only one journalist in the above 35 group (H.) is optimistic in his answer, but his situation is different, considering that his paper has absorbed the staff of a competing outlet:

Many publications have downsized or closed their investigation departments. But many are powering on. At my paper, we had 19 journalists in the investigation department when I joined in 2015, and now [in 2018] there’s 29.

Negative appraisals of the state of investigative journalism run the gamut from resignation in the younger interviewees to a sense of outrage in their older peers. M., aged 25, belongs to the former category, deploring that “the current government doesn’t like it when we say critical things and when we investigate things that do not reflect the central socialist values or fit the leaders’ desires” (interview in Beijing, 23 November 2018). Z.B., who is 32, complains about copy-and-paste culture:

An investigation requires a lot of time, travel, interviews, energy, and resources. But once you’ve put in the work, other journalists will just copy and paste it, with no respect for intellectual property. They just sit in front of their computers, use and alter your work and they have a good readership! You try to defend yourself but no one will help. They’ll say, this is public information, why wouldn’t other people be allowed to use it? This is why I’m saying that even within the profession, investigation isn’t encouraged. (Interview in Guangzhou, 29 November 2018)

The journalists over 35 have harsher words about the current situation. “A few years ago, once the story was written, it’d be published straight away, since no government department would intervene and tell you something. Now, at any moment, they can tell you that the piece won’t get published,” C. complains. I. goes further:

In the past we used the phrase “supervision by public opinion”; now it’s “constructive supervision.” They keep adding adjectives... But all these concepts are fuzzy. What does that even mean, constructive supervision? If I don’t want you to be supervising, I’ll tell you that what you’re doing isn’t constructive. That’s why all these preconditions are set. Of course, we want the problem we’re investigating to be resolved. But to me, solving the problem, finding a solution, that’s the authorities’ business. It’s not an obligation for me to take on.

“Now is the worst time for investigative journalism. I don’t need to add it’s the government’s fault, right?” asks V. sarcastically. He goes on to comment on a “worrying vicious circle”:

The traditional media have been challenged by the rise of the “personal media” (zimeiti 自媒體).14 Those reveal facts in a fragmented manner. They circulate things that are consumed very quickly. This impacts the investigative journalist’s work because in the past, you’d be able to go into the field for eight to ten days and work in peace, but now you’re working and the news has already been consumed. Then again, there are differences between your investigation and the piecemeal stuff that has spread on social media. When your story breaks, they tell you it’s false. So, the reputation of investigative journalism is harmed. The profession is losing credibility in the eyes of the public at the time when society most needs it. But neither the government nor civil society encourages it.

However, the most severe assessments of the state of journalism under Xi Jinping were made by journalists over 35 or individuals who were no longer journalists at the time of the interview. “There’s no more investigative journalism, so you can’t use the word encouragement!” A. asserts (interview in Shenzhen, 27 November 2018, age 45).

According to Y., “it’s a different time now. There’ll be an investigation or two occasionally, but there’ll no longer be investigative journalists. The profession will disappear. It’s like the cavalry in the army: it may have been powerful in the past, but it no longer exists.”

It is hard to say whether the severity of these former journalists reflects stricter professional values. It is, however, possible that it is easier for them to express critical views now that they are no longer on the job. At any rate, A., a former journalist from Nanfang dushibao, appears to have a selective memory as he expresses his nostalgia for a “golden age of journalism” that he dates back to “the late 1990s and early 2000s” but forgets that censorship and self-censorship on sensitive political topics also existed then. Such stances suggest to K., who is 37, that “people always tend to embellish the past and continually complain about the journalistic profession not being as good as it used to be.”

The role of social evolution

The responses of the investigative journalists interviewed for this study confirm that divergences in professional values between the two generations are partly explained by transformations in the news media ecosystem. The analysis of biographical data shows that changes in academic training and in social origins, as well as the key role of internship supervisors in passing on professional values, must also be considered.

The influence of academic training

Out of the 29 journalists, 12 studied in the journalism and communication department (xinwen chuanbo xueyan 新聞傳播學院) of a Chinese university. None was trained in journalism abroad. The other 17 studied Chinese, law, economics, etc., and more rarely scientific subjects such as mathematics or computer science.

However, the proportion of journalism and communication graduates is reversed between the two generations: only four out of the 18 journalists over 35 compared to eight of the 11 under 35. From one generation to the next, getting a degree in the journalism and communication department of a university has become the rule, when it used to be the exception. This has gone hand-in-hand with the increase in the number of journalism and communications programmes in universities, from 51 in 1989 to 124 in 1999 and 877 in 2008,15 the number of students serviced increasing from 723 to nearly 150,000.

Combined with the lengthening of studies, the spectacular boom of university programmes in journalism and communication has contributed to an increase in the skill levels of junior reporters. This is to some extent because these programmes increasingly include technical classes that are useful for information collection and processing. The older journalists recognise this: “In my newspaper, the new hires all have a master’s degree, often in journalism, and they have professional knowledge in technical areas,” Z.C. observes.

Yet, on the other hand, universities have been subjected to stricter ideological control since the 1990s, particularly in journalism and communication departments, contrasting with the more liberal atmosphere that prevailed on campuses in the 1980s. Since the repression of the 1989 demonstrations, universities are required to teach students Marxism, along with the thought of Mao Zedong 毛澤東, Deng Xiaoping 鄧小平, and now Xi Jinping. Additionally, the main journalism and communication programmes have operated under the “joint governance” (buxiao gongjian 部校共建) system since 2003. Initially adopted by the School of Journalism at Shanghai’s Fudan University in 2001, it has placed academic programmes under the supervision of the propaganda department.16 Joint governance gives lecturers less control over course materials, and foreign exchanges are subject to heightened control by the Communist Party. The objective is to ensure that students are trained to comply with the rules of socialist journalism, not familiarised with freedom of the press. Since Xi Jinping’s access to power, universities have also banned discussion on seven sensitive issues, including freedom of the press.17

Admittedly, it has been shown that some lecturers do retain some alternative discursive elements and that students only superficially support the Party’s ideology (Repnikova 2017b). Yet, the crux of the issue is not only the Party attempting to force ideology on students; it also obstructs access to some knowledge, particularly pertaining to the history of Chinese journalism. How else are we to explain the fact that the over 35s who did not study journalism at university are more proficient in the history of Chinese media than their younger counterparts who attended these classes? Some cite the influence of journalists and outlets from the end of the Qing dynasty and of the Nationalist period. For instance, R. brings up Huang Yuanyong 黃遠庸, who opposed the imperial restoration plans of Yuan Shikai 袁世凱 in the early twentieth century; C. expresses his admiration for Ta Kung Pao (Dagongbao 大公報), which was founded by Zhang Jiluan 張季鸞 in 1926 under the Nationalist regime and steadfastly refused to be affiliated with a party. Others mention Liu Binyan 劉賓雁 and his stories in People’s Daily (Renmin ribao 人民日報) in the 1980s. Not a single academic graduate under 35 brings up this type of reference.

More members of the over 35 group also cite foreign influence – especially from the US – on their approach to investigative journalism. Some mention having read books on the Watergate case and pieces by Pulitzer Prize winners: “We would learn from American journalists how they investigated and wrote,” Y. remembers. “We’d wait for the Pulitzer Prize announcements every year.” “At the university, I didn’t like Chinese journalists and Chinese journalism theories. I would read Pulitzer Prize winners, Wall Street Journal reporters, and books by foreign war correspondents,” says Z.C. Again, none of the under 35 journalists mention reading these kinds of books.

The importance of social origins

Only nine out of 28 investigative journalists18 were born in families in which at least one of the parents was a member of an upper socio-occupational category (executives, professors, engineers, etc.); the others have working-class backgrounds (workers, farmers, small business owners, schoolteachers). The distribution varies between the generations: the proportion of working-class backgrounds is far higher among the over 35 (nearly 75%). Conversely, nearly half of the under 35 journalists were born to upper-class parents.

Whatever their generation, many journalists from working-class families claim that their social origins strongly influence the way in which they see their job. “Many investigative journalists sincerely want to help provide solutions for the problems encountered by underprivileged individuals and groups,” notes N., the son of farmers (interview in Beijing, 19 November 2018, age 39). Also a son of farmers, I. says that his role consists in “trying to find a solution for people who are vulnerable, for the little guy.” This motivation led many of them to move to Guangzhou and join the Nanfang Media Group. For U., another son of farmers, who comes from a second-tier city in Hebei and is employed by a weekly in Guangzhou: “A great many investigative journalists from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s were from the countryside or from an urban working-class background. Most of them didn’t come from wealthy families; they were rather poor. They had an inferiority complex and they were very eager to share their perspective on society” (interview in Guangzhou, 30 November 2018, age 30). H., who comes from a village in Sichuan Province, is eloquent on the topic:

I came from the countryside; my parents were farmers. You have to understand what it means for country kids to leave their remote spot and come into the city, find a job, and get some success with their writing. My university tuition fees were paid by donations. This goes hand-in-hand with a commitment to social justice for farmers and the little people. Why do I do this, why do I keep getting to the bottom of the issues? I think it has to do with my origins. My background. Why do so many investigative journalists come from the country? And why are city people fewer in our profession? Because it’s a difficult, tough, badly paid profession, without guarantees and with risks. People who were born in the city have more opportunities: they can go abroad, they have better jobs and better wages. They’re in no hurry to bring justice to the lower social classes, because they’re not part of them!

Differences in geographical origin confirm the importance of social origins. A total of 21 journalists out of the 29 interviewees come from provinces in the interior of China (Gansu, Guizhou, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hunan, Jiangxi, Jilin, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Sichuan), whereas eight are from coastal provinces, from Guangdong to Liaoning: the journalists from the least developed provinces are clearly overrepresented, which reflects previous observations on the number of investigative journalists from the interior, which earned them the nickname of “Hunan gang” (Hunan bang 湖南幫).19 As in the case of academic training, there is a trend reversal between the two generations: aside from a single exception, the journalists over 35 all come from provinces in the interior, whereas only four out of the 11 in the under 35 group do. The geographical factor is particularly indicative of the importance of the social factor, in that most journalists from the interior of China were born in second-tier cities, not provincial capitals. Conversely, only among the under 35 do we find journalists who were born in wealthy coastal provincial capitals such as Hangzhou and Nanjing.

Having come to study and work in the big coastal cities, they have first-hand experience of the wealth gap between the Chinese provinces and between urban and rural dwellers (Tong 2013). They are also aware of the inequalities in rights resulting from the conditions of the hukou 戶口.20 In the 1990s and 2000s, these personal experiences fuelled an interest in social matters and in the defence of unprivileged social groups (ruoshi qunti 弱勢群體), illustrated by the Sun Zhigang case in 2003.

The crucial role of internship supervisors

Lastly, another contributing factor in the transformation of professional values in investigative journalists is to be found in the crucial role of supervisors during the journalism students’ internships in news media outlets. P. emphasises the essential role played by her supervisor when she interned at Southern Weekly (Nanfang zhoumo 南方周末):

It was my first job. I didn’t know anything about journalism. I couldn’t write even short stories properly. My supervisor really helped me a lot. Also his philosophy about journalism. He told me that if I wanted to be a journalist I should know that investigation is the most difficult challenge and also the most important for journalism. No other single person has had as great an influence on me as my supervisor. (Interview in Shanghai, 19 November 2019, age 37)

Likewise, U. also discovered investigation through his supervisor during an internship at Nanfang dushibao:

I wanted to become a writer, and my supervisor got me into investigation. With him, I discovered that this is a pure and simple way of doing things; you’re not affiliated with a given interest group. The investigative journalist will not say anything he doesn’t believe; he only writes about what he has seen and reflected upon, what he considers to be right.

“My internship supervisor taught me how to go the extra mile, how to investigate. Thanks to him, and thanks to the example of other journalists, I understood what you have to do to become a good journalist,” H. says.

In many cases, meeting their supervisor convinced students who were wavering that this was the job they should be doing. “By the end of my internship, I was no longer considering doing another job,” M. remembers. U. also clearly recalls that it was upon completing his internship that he “became set on working as an investigative journalist and gave up on [his] dream of being a writer.”

In the 1990s and 2000s, internship supervisors were experienced journalists, and often practitioners of investigation. The journalists aged 40 and over today thus encountered great names in the investigative journalism field of that time during their internships, such as Deng Fei 鄧飛, Luo Changping 羅昌平, and Wang Keqin 王克勤. These people taught them the tricks of the trade, and inspired them through their examples and their professional values. “During my internship at Nanfang zhoumo, I was able to meet many brilliant investigative journalists,” M. notes. “They were all brilliant. They were good people, meaning people with a noble ethic, who are not looking to further their own interest, who do things for the public interest and for the truth. These people inspired me.” The 2010s, however, saw an exodus of these experienced journalists, who were fired or quit after coming to the conclusion that they could no longer work in accordance with their ethos.21 This “Dunkirk of investigative journalists,” to use Y.’s phrase, interrupted the transmission of professional values between the old and the new generation.

Conclusions

The two generations of investigative journalists studied here express different views about the freedom to choose topics, the scope of investigation, and their relationships to power. This discrepancy on these three fronts appears to indicate an erosion of professional values among the under 35 journalists in comparison to journalists over 35. This is supported by claims made by former journalists about the death of investigative journalism and confirmed by a study that notes “a reinforced Party ideology on the individual level” (Chen 2021). In comparison to the work of Wang Haiyan, this study emphasises the importance of the academic factor in the evolution of professional values, due not only to the increase in the proportion of young journalism graduates, but also to their lesser exposure to knowledge outside of the Party narrative. Another central factor is the departure of the older generation of internship supervisors. Still, it cannot be said that a radical shift in professional values occurred between the two generations.

Additionally, since the latest interviews were conducted for the purposes of this study in November 2019, journalists have done work that shows that investigation is not dead, including sometimes on national topics. An example is provided by the work of a team of Caixin 財新 journalists led by Gao Yu 高昱 in Wuhan during the first weeks of the Covid-19 epidemic in 2020. Having spent 76 days in lockdown in Wuhan, they demonstrated that several weeks were lost in the fight against the epidemic because the authorities had stifled warnings from doctors about the emergence of a new virus.22 Other investigations deserve mention, such as those on food delivery couriers published by Renwu 人物 magazine in September 2020,23 and on the surrogate motherhood business in The Beijing News (Xinjingbao 新京報) in January 2021.24 Ultimately, while there has been a clear decrease in the number of investigative journalists and an effort by Xi Jinping to control the media closely, a form of “supervision by public opinion” still exists. As Maria Repnikova has noted, the “pockets of critical journalism have shrunk, but have managed to survive and redefine themselves in the Xi era” (2017a: 213).

Still, the freedom of investigative journalism has narrowed under Xi Jinping. On 7 April 2020, Gao Yu explained that his team found far more about the situation in Wuhan than was published in the magazine: “We’ve probably uncovered 75% to 80% of the truth. What we’ve published only amounts to 30% to 40%.”25 We are a long way from 2003, when Caijing 財經 demanded transparency from the authorities regarding the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic.26 In a podcast aired by Caixin in February 2021, a year after his investigation in Wuhan, Gao Yu regretted that “the lessons [of Wuhan] have already been ignored. And we can see few people even asking questions.”27 He attributes this to the attacks investigative journalists face by nationalist commentators. Instead of examining the facts, these “keyboard warriors” blame them for providing foreigners with arguments to criticise China. They “besiege anyone on Weibo who dares to reveal the scars” of natural and human-made disasters. “The ranks of the self-confident are swelling, while those with critical thoughts are busy with self-mutilation.” Gao Yu gathers from this that “all the efforts toward enlightenment over the past 30 years, they have failed. More and more of the people we hoped to help in breaking free from terror have become the ones who despise us more than those who oppress them.”

The rise of nationalism evoked by Gao Yu gives a further dimension to the transformation of the media ecosystem that has occurred since the early 2010s and to its impact on the professional values of investigative journalists. At their level, the changes in academic training and social origins evidenced in this paper also contribute to the transformation of these values. They are a discreet ingredient, but likely one with long-term effects in the growing tendency of investigative journalists to conform to Party expectations and to exercise less critical thinking.

Acknowledgements

This article was translated from French by Jean-Yves Bart, with support from the Maison Interuniversitaire des Sciences de l’Homme d’Alsace (MISHA) and the Excellence Initiative of the University of Strasbourg.

Manuscript received on 20 September 2021. Accepted on 27 September 2022.

References

BAI, Hongyi. 2013. “Between Advocacy and Objectivity: New Role Models among Investigative Journalists.” In Marina SVENSSON, Elin SÆTHER, and Zhi’an ZHANG (eds.), Chinese Investigative Journalists’ Dreams: Autonomy, Agency, and Voice. Lanham: Lexington Books. 75-90.

BANDURSKI, David, and Martin HALA. 2010. Investigative Journalism in China: Eight Cases in Chinese Watchdog Journalism. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

CHEN, Mengshu. 2021. Digital News and Negotiated Agency: The Digital Transition within China’s Newspapers. PhD Dissertation. Montreal: Concordia University.

GUAN, Jun. 2020. Silencing Chinese Media: The Southern Weekly Protests and the Fate of Civil Society in Xi Jinping’s China. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

HASSID, Jonathan. 2011. “Four Models of the Estate: A Typology of Contemporary Chinese Journalists.” The China Quarterly 208: 813-32.

———. 2016. China’s Unruly Journalists: How Committed Professionals are Changing the People’s Republic. London: Routledge.

PETER, Alain. 2019. “Negotiations and Asymmetric Games in Chinese Editorial Departments: The Search for Editorial Autonomy by Journalists of Dongfang Zaobao and Pengpai/The Paper.” China Perspectives 119: 45-52.

REPNIKOVA, Maria. 2017a. Media Politics in China: Improving Power under Authoritarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2017b. “Thought Work Contested: Ideology and Journalism Education in China.” The China Quarterly 230: 399-419.

STOCKMANN, Daniela. 2013. Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

STRITTMATTER, Kai. 2019. We Have Been Harmonized: Life in China’s Surveillance State. New York: Custom House

SVENSSON, Marina, Elin SÆTHER, and Zhi’an ZHANG (eds.). 2013. Chinese Investigative Journalists’ Dreams: Autonomy, Agency, and Voice. Lanham: Lexington Books.

THOMSON, Stanley Bruce. 2011. “Sample Size and Grounded Theory.” JOAAG 5(1): 45-52.

TONG, Jingrong. 2011. Investigative Journalism in China: Journalism, Power, and Society. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.

———. 2013. “The Importance of Place: An Analysis of Changes in Investigative Journalism in Two Provincial Newspapers.” Journalism Practice 7(1): 1-16.

———. 2015. Investigative Journalism, Environmental Problems and Modernisation in China. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

WANG, Haiyan. 2016. The Transformation of Investigative Journalism in China: From Journalists to Activists. Lanham: Lexington Books.

———. 2021. “Developing Mannheim’s Theory of Generations for Contemporary Social Conditions.” Journal of Communications 71: 104-28.

ZHAO, Yuezhi. 2000. “Watchdogs on Party Leashes? Contexts and Limitations of Investigative Reporting in Post-Deng China.” Journalism Studies 1(4): 577-97.

———. 2008. Communication in China: Political Economy, Power, and Conflict. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

[1] “China Advertising Industry Report, 2013,” Businesswire, 5 August 2013, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20130805005642/en/Research-and-Markets-China-Advertising-Industry-Report-2013 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

[2]François Bougon, 2018, Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping, London: Hurst Publishers.

[3] “Xi Jinping’s 19 August Speech Revealed? (Translation),” China Copyright and Media, 12 November 2013, https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2013/11/12/xi-jinpings-19-august-speech-revealed-translation (accessed on 10 September 2021).

[4] “習近平: 新聞輿論工作各個方面, 各個環節都要堅持正確導向” (Xi Jinping: Xinwen yulun gongzuo gege fangmian, gege huanjie dou yao jianchi zhengque daoxiang, Xi Jinping: In all respect, at all stages, the work of informing public opinion must comply with the proper orientation), Pengpai (澎湃), 19 February 2016, https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1433753 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

[5] “一圖速覽! ‘中國新聞事業發展報告(2022年發布)’,” (Yi tu su lan! “Zhongguo xinwen shiye fazhan baogao (2022 nian fabu),” Summary of the “Report on the development of journalism in China (Edition 2022),” Zhongguo jizhe wang (中國記者網), 16 May 2022, www.zgjx.cn/2022-05/16/c_1310594629.htm (accessed on 12 June 2022).

65 “被收容著孫志剛之死” (Bei shourongzhe Sun Zhigang zhi si, Detainee Sun Zhigang dies), Nanfang dushibao (南方都市報), 25 April 2003, https://news.sina.com.cn/s/2003-04-25/11111016223.html (accessed on 7 December 2021).

7 “松花江之痛: 沿江百姓知情權如何保證” (Songhua jiang zhi tong: Yanjiang baixing zhiqing quan ruhe baozheng, The pain of sending flowers to the Songhua River: How to guarantee the right of riverside residents to be informed)), Caijing (財經), 28 November 2005, http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2005-11-28/10518425200.shtml (accessed on 10 September 2021).

8 “奪命的是建築物而不是地震: 被忽視的抗震設防問題” (Duo ming de shi jianzhu wu er bushi dizhen: Bei hushi de kangzhen shefang wenti, Loss of life due to construction, not the earthquake: Problems of neglected anti-seismic fortifications), Nanfang zhoumo (南方周末), 29 May 2008, www.infzm.com/content/12756 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

9 The phrase “supervision by public opinion” (yulun jiandu 輿論監督) first appeared in official Party discourse at the Party’s Thirteenth National Congress in October 1987, in the introductory report presented by Secretary-General Zhao Ziyang 趙紫陽.

10 Zhang Zhi’an 張志安 and Cao Yanhui 曹艶輝, “中國的調查記者呈衰落之勢” (Zhongguo de diaocha jizhe cheng shuailuo zhi shi, Chinese investigative journalists show signs of decline), Sohu (搜狐), 7 December 2017, http://news.ifeng.com/a/20171207/53936712_0.shtml (accessed on 10 September 2021).

11 Hassid (2011) describes four ideal-types of Chinese journalists: Communist professionals, workaday journalists, advocacy professionals, American-style professionals.

12 Qian Gang 錢鋼, “中國傳媒的發展路向,” (Zhongguo chuanmei de fazhan luxiang, The meaning of the development of Chinese media), China Digital Times (中國數字時代), 17 January 2013, https://chinadigitaltimes.net/chinese/275021.html (accessed on 6 July 2022).

13 The Chinese term for government, zhengfu 政府, refers to the political authorities: the Communist Party and/or the state.

14 Zimeiti 自媒體 are social media accounts on which individuals post news, opinions, and comments.

15 Wu Tingjun 吳廷俊, “改革開放30年是新聞教育發展最快30年” (Gaige kaifang 30 nian shi xinwen jiaoyu fazhan zui kuai 30 nian, The 30 years of reform and opening up have seen an unprecedented development of journalism teaching), Sohu (搜狐), 27 October 2008, http://news.sohu.com/20081027/n260264900.shtml (accessed on 10 September 2021).

16 Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 中華人民共和國教育部, “共築新聞人才的成長搖籃: 部校公建高校新聞學院綜述” (Gongzhu xinwen rencai de chengzhang yaolan: Buxiao gongjian gaoxiao xinwen xueyuan zongshu, Building a cradle for journalistic talent together: The Ministry of Education and the Department for Propaganda are jointly developing university journalism departments), 16 September 2014, www.moe.gov.cn/s78/A08/moe_745/201409/t20140918_175094.html (accessed on 10 September 2021).

17 “關於當前意識形態領域情況的通報” (Guanyu dangqian yishi xingtai lingyu qingkuang de tongbao, Circular on the situation in the ideological sphere), also called Central Committee Document No. 9, April 2013. The document was circulated abroad by the journalist Gao Yu 高瑜, who in 2015 was sentenced to seven years in prison for divulging state secrets.

18 One journalist did not mention his parents’ occupations.

19 Zhang Zhi’an 張志安 and Cao Yanhui 曹艶輝, “中國的調查(…)” (Zhongguo de diaocha (…), Chinese investigative (…)), op. cit.

20 The hukou 戶口 is a system for registering and controlling the population in China. It classifies citizens as urban or rural dwellers; the former are granted more rights.

21 This exodus is still underway: three investigative journalists aged over 35 who participated in this research have left the profession since they were interviewed.

22 Gao Yu, Xiao Hui, Ma Danmeng, Cui Xiankang, and Han Wei, “In Depth: How Wuhan Lost the Fight to Contain the Coronavirus,” Caixin (財新), 3 February 2020, https://www.caixinglobal.com/2020-02-03/in-depth-how-wuhan-lost-the-fight-to-contain-the-coronavirus-101510749.html (accessed on 6 July 2022).

23 “外賣騎手, 困在系統里” (Waimai qishou, kun zai xitong li, Couriers trapped by the system), Renwu (人物), 8 September 2020, https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1677231323622016633&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 6 July 2022).

24 “地下代孕‘流水線’: ‘手術室’里的孕媽, 卵妹和被退單的棄嬰” (Dixia daiyun “liushuixian”: “Shoushu shi” li de yunma, luanmei he bei tuidan de qiying, The clandestine “assembly line” of surrogate motherhood: Surrogates, egg donors, and the resale of undesirable newborns in the “operating room”), The Beijing News (新京報), 25 January 2021, https://www.bjnews.com.cn/detail/161156385715113.html (accessed on 6 July 2022).

25 Fan Jiaxun, Hou Yuezhu, and Han Wei, “Reporter’s Notebook: Our 76 Days Locked Down in Wuhan,” Caixin (財新), 7 April 2020, https://www.caixinglobal.com/2020-04-07/caixin-reporter-our-70-days-and-nights-in-wuhan-101539718.html (accessed on 6 July 2022).

26 “SARS 催促行政透明” (SARS cuicu xingzheng touming, SARS calls for transparency from the administration), Caijing (財經), 20 April 2003, http://finance.sina.com.cn/g/20030420/2007333267.shtml (accessed on 6 July 2022).

27 Gao Yu’s original text was censored. Copies can be found, such as: “高昱:財新一位副主編的年終总結: ‘三十年启蒙失敗了’” (Gao Yu: Caixin yiwei fu zhubian de nianzhong zongjie: “Sanshi nian qimeng shibaile,” End-of-year thoughts by Gao Yu, Caixin deputy editor: “The thirty years of enlightenment have failed”), 21 February 2021. China Media Project published an English version: https://chinamediaproject.org/2021/02/24/thoughts-on-a-dark-year (accessed on 6 July 2022).