BOOK REVIEWS

Revisiting Deliberative Governance: The Case of Land Transactions in Rural China

Rongxin Li is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the School of Government, and research assistant at the Research Centre for Chinese Politics, Peking University. No. 5 Yiheyuan Road, Haidian District, Beijing, People’s Republic of China, 100871 (johnsonli2.aiesec@gmail.com).

Renhao Yang is a PhD candidate at the Division of Geography and Tourism, KU Leuven. Celestijnenlaan 200e, 3001 Leuven, Belgium (renhao.yang@kuleuven.be).

Introduction

A normative shift on the study of deliberative democracy in authoritarianism (He 2006, 2014; He and Warren 2017; He and Wagenaar 2018) provides a solid theoretical backdrop for further exploration of deliberative governance in the Chinese context with the rather paradoxical coexistence of authoritarianism and deliberation. Also, Chinese official propaganda in the last two decades has facilitated the image of deliberative governance, especially in the grassroots of autonomous regions, without eroding the regime’s authoritarianism. Flourishing grassroots deliberative practices in the last two decades have motivated many authors and practitioners to further rethink this possible public empowerment method (or potential bottom-up quasi-democratic reform in China’s grassroots) in authoritarianism.

To many, the deliberative concept of democracy endorses a way in which the empowered public can actively participate in interactions between the public and government. However, this ideal varies in different political contexts, in China as elsewhere. Self-admitted authoritarian states most often adopt a deliberative method with a factionalist side to further solve practical problems on the one hand, while simultaneously maintaining social order and enhancing the local regime’s legitimacy on the other hand. Unlike Western democratic and procedure-based deliberation, this hybrid deliberative governance in China’s grassroots reconciles some traditions which many authors have identified as Confucian deliberation (Lyon 2004; He 2014), while presenting itself in some modern settings such as the Village Council (cunmin yishihui 村民議事會) and the Village Committees-Collective Asset Management Company (cunmin weiyuan hui 村民委員會 – jihe zichan guanli yewu 集合資產管理業務, hereafter VC-CAMC) in our case. These designs carefully check and balance villagers’ resistance brought about by benefit misdistribution, and they facilitate a stable yet controllable policy implementation. For this purpose, we chose for our case study a village land transaction in which confrontations among officials, investors, and villagers and some potential uncertainties were deliberatively dispelled in grassroots governance.

China’s unprecedented urbanisation process has pumped up great demand for urban construction land in and around its major cities (Yang and Yang 2021). Moreover, a considerable amount of underutilised rural construction land has remained undeveloped due to dichotomous land ownership, i.e., dual-track land ownership between the state and rural collectives – the state owns urban land, while the rural collectives own rural land communally. According to China’s Land Administration Law, state expropriation is the only way to commandeer rural land for urban development. This precipitates considerable rural unrest mainly by causing compensation incongruence between the state’s offer and peasants’ demands. Additionally, in practice, under-the-table trading in rural land between urban and rural authorities is pervasive and rampant, adding corruption to the reasons for rural discontent.

To maintain high-speed economic development and alleviate the rural unrest caused by land expropriation, the Chinese state introduced market-oriented reform under the name of Rural Collectively-owned Commercial Construction Land (農村集體經營性建設用地 nongcun jiti jingying xing jianshe yongdi, hereafter RCCCL) in 33 pilot areas in 2015. Unlike traditional ways of expropriating land from villagers, RCCCL enables external investors to purchase usage rights for nonfarm use for 40 to 50 years from rural collectives. Also, RCCCL is transforming illegitimate transactions into legal trade in the land commodification process, as a result of which more capital is flowing into the countryside, producing an enormous amount of construction land that becomes a commodity, and which can be bought and sold in a “fictitious market.” Meanwhile, it also means an increasing number of forces have been taking part in rural affairs, leaving questions open about whether this new wave of land commodification in rural Chinese villages can be safely folded into grassroots governance, and whether a more active deliberative approach can be an effective tool in a pragmatic sense.

We begin by theoretically revisiting the general idea of deliberative governance and its special application in the Chinese context. We next present case studies on RCCCL reform in rural Chinese villages in order to further look into the interactions between and among various stakeholders. In this way we examine how a deliberative approach is adopted to quell grassroots uncertainties (e.g., the villagers’ protests and petitions), and how this equilibrium can be efficiently handled in grassroots politics. Unlike land expropriation in the past that needed to convert collectively owned land to state-owned land (the nationalisation of land) for urban construction, RCCCL allows for a direct transaction of collectively-owned land to external investors. This means that the state is no longer the only proprietor of construction land. Therefore, this reform introduces more diverse participants into grassroots governance, and poses new challenges.

Deliberative governance in democracies and authoritarian states revisited

Deliberation is not naturally interlinked with democracy. In a minimal definition, deliberation refers to “mutual communication that involves weighing and reflecting on preferences, values, and interests regarding matters of common concern” (Bächtiger et al. 2018: 31). Although deliberation was initially understood as something specific to elite, even Bessette (1997), who proposed this idea, also discussed deliberation in American bureaucracy. Nonetheless, deliberation was still endowed with some positive meanings, where people’s justifications, preferences, and judgements are likely to be transformed by free and equal deliberations among them. Habermas (1983) expands the frontiers of deliberation into the public sphere in his concept of two-track deliberation, as when deliberation was democratically linked with democracy and conceptually contrasted to aggregative democracy in the modern representative system.

Before discussing how deliberation can be differently reconciled with governance both in democracies and authoritarian states, it is necessary to be wary of deliberation on some occasions being conceptually stretched and empirically generalised.[1] Sartori (1970) and Collier and Levitsky (1997) warned of the dangers of stretching the concept in political science, and more recently, Steiner (2008) has criticised the fact that deliberation per se has become virtually a “synonym for talk of any kind.” This concern is justified; though the study of deliberation or a more faddish idea of deliberative democracy is fruitful and rigorous, the special meaning of deliberation should be kept. Statements of this kind are firmly based on the classical definitions of deliberation, where “reason” and “common good” are the sole criteria for assessing if an interaction or communication qualifies as deliberation, or if it is a good or bad deliberation (Habermas 1983). In this sense, the increasing literature on empirical studies of deliberation is misleading where the concept is defined as something opposite to such a definition.

If this is the case, deliberation is likely to be only ideal. Two pathways nevertheless can dispel this dilemma by revisiting the two central questions of what constitutes a democratic deliberation and how to understand deliberation in a deliberative system. When Mansbridge (2007) distinguished between deliberative democracy and democratic deliberation, she adopted a “neo-pluralist” tradition by expanding the frontiers of rational discourse and common good. Deliberation should not be exhausted only by reason (what others describe as skills, capacities, good manners, reasonableness, etc. (Rosenberg 2007)); certain dialogue practices, reason-like in communication, could also be deliberative – for example, emotion, storytelling, rhetoric, and even some dialogues of disempowerment, especially when they sincerely respond to practical deliberation. The same understanding could also be applicable in the core of the common good, where a meta-consensus (Landwehr 2015) could aid participants by identifying common concerns rather than forcing them to do so.

A “deliberative system” proposed by Mansbridge et al. (2012) can also respond to this dilemma. Such a systemic approach provides the possibility of rethinking deliberative capacities beyond a single deliberative institution, while simultaneously helping to depict a broader deliberative image in large-scale societal terms by including various communicative forms. This means that a deliberative system more likely emphasises interactions and complementary roleplay among different parts in a dynamic whole. Therefore, a crucial assessment of deliberation seems not so important. This analysis facilitates finding a way to introduce deliberation into governance where government and society are intricately interlinked and interact in an organic system. A systemic approach could therefore rectify some irrational overemphasis, thus optimising governance in a more coordinated manner. These two traceable clues of a return to the core pillars of deliberative democracy and a “deliberative system” approach are theoretically and practically helpful in analysing a government-led and functionalist-oriented type of deliberation in China.

Deliberative governance can be traced back to John Stuart Mill’s ideas of “government by discussion.” Qualified deliberations in governance are described as communicative interactions that can shift the normative governmental model to more citizen-inclusive and legitimised decision-making. It helps citizens “make sense together” by figuring out individual preferences deliberatively (Mill 1975). In this sense, deliberative governance can facilitate these constructive conversations to avoid irrational outcomes, and create a shared sense of the common good and better voting (Bohman 1998; Chambers 2003). As Rehg and Bohman (1996: 79) would have underscored, “political decision-making is legitimate insofar as it follows upon a process of public discussion and debate in which citizens and their representatives, going beyond their mere self-interest and limited points of view, reflect on the public interest or common good.” In modern governance, a deliberative approach redraws the relationship between representatives and the represented.

There are good reasons to reemphasise the importance of (deliberative) governance. First is the emergence of bad governance, which in turn leads to a democratic crisis where “lagging economic growth, poor public services, lack of personal security, and pervasive corruption are commonly seen, and citizens of such countries understandably feel disappointed by democracy” (Plattner 2015: 7). Diamond (2015) has criticised the bad governance that afflicts most (although not all) nondemocratic countries and new democracies. However, if this is the case, how is it possible to explain the extreme incompetence of governance in some established democracies? This question is particularly relevant at a time when the legitimacy of many democracies around the world depends less on the deepening of their democratic institutions than on their ability to provide high-quality governance.

In terms of good governance, a deliberative approach is analytically useful in thinking about a different type of deliberation that operates in some authoritarian settings, especially in the case of adopting more pragmatic deliberative techniques for good governance, rather than those assumed by democratic theories. Indeed, the seemingly widespread establishment of various deliberative institutions in Chinese governments at all levels constitutes a more up-to-date governance model and hybrid regime type, which is commonly seen as the key to China’s authoritarian resilience. Some successful instances have assumed public form in the cases of interactions between cadres and citizens. Even in some Western Chinese studies, deliberation is not always antagonistic to coercion (e.g., authoritarian deliberation in China).[2] Conversely, deliberation may travel more easily in some authoritarian regimes. This logic explains why deliberation in authoritarianism is likely being adopted to provide good governance in a controllable way, or to achieve collective and substantial goals, rather than for the purposes of empowerment.

In essence, prudent deliberation rather than elections is more acceptable to regimes that for whatever reason seem unlikely to adopt liberal electoral democracy.[3] Although a deliberative approach cannot achieve a very decisive role in producing collective outcomes, it is still possible to develop some ideas about how governance in practice may succeed or fail in deliberative terms. We therefore summarised three implications of (grassroots) deliberation in China’s authoritarianism, namely, functionalist and legitimacy considerations, and a pursuit of democratic-like political reforms. First, the quality of authoritarian governance heavily relies on its responsiveness to citizens’ complaints (although most of these complaints are not deliberative). These hierarchical communicative interactions simply transmit underlying messages from the public to higher levels. A quantitative study conducted by Chen and Xu (2017) indicates that more than half of the public complaints are properly resolved via some deliberation-like method. This pragmatic consideration facilitates responsive governance while also alleviating large-scale citizens’ collective actions.

Second, a deliberative concept of good governance is interlinked with legitimacy; this linkage is consolidated in non-Western-style regimes such as China and Singapore. Yu Keping, for example, concludes that “good governance will be the most important source of political legitimacy for human society in the twenty-first century.” (2011: 16) This legitimacy transformation based on good governance, or even deliberative governance, may potentially serve as the main source of political legitimacy in contemporary China. Third, modern authoritarianism is based on democratic-like political reform, rather than on a monolithic one. A society may accommodate deliberations that are far removed from state power. Such deliberative governance works more easily at the autonomous grassroots in China, in particular.

These three dimensions of good governance, regime legitimacy, and empirical feasibilities depict deliberative governance in Chinese authoritarianism. To justify how such a deliberative approach can possibly be embedded in and reconciled with Chinese governance, and especially how it is developed to address the hard issue of land transactions, we have methodologically combined both the political and capital nexus[4] in practice and conducted our case studies with a focus on mutual interactions amongst various participants, and a deliberative equilibrium retained after this deliberation.

Methodology

We conducted three rounds of fieldwork in Pidu District in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, which was in the first batch of 33 county-level pilot regions for RCCCL reform. From February 2017 onward, our preliminary fieldwork in Pidu’s Baiyun Village amassed close connections with local informants and eased the way for accessing core sectors such as the Village Committees (VCs), urban construction offices at the town(ship) level, and some land project sites. From July 2019 to January 2021, we reexamined our fieldwork in Pidu to check on the policy implementation and deliberative resolutions, which confirmed our conclusions. We thus expanded the scope of our fieldwork to two other villages, Hanjiang and Koujiaba (bound together in one RCCCL project), besides Baiyun. All three villages are located in Hongguang, a town in western Pidu District.[5]

Our empirical information was collected from these three villages and Hongguang Town, including interviews with 52 village cadres, villagers, and investors, as well as some other stakeholders, such as policy consultants and government staff, in order to disentangle the perplexing political relationships amongst these main participants. Simultaneously, textual analysis of village genealogies and official/legal documents at various levels was also carried out in field sites, with a further contextualisation of the transcriptions of interviews and field notes. These primary and secondary data and documents paved the way for the even more ambitious goals of understanding the political power-capital relationships and interactions amongst those stakeholders in RCCCL reform via qualitative approaches. We also worked on a focus group (in which villagers disagreed with the compensation proposed by village cadres or investors, and then resorted to petitions, non-cooperation, and refusal to transfer land) by analysing their behavioural logic and way of thinking, and how they changed their minds and came to a compromise after communicating and deliberating with the others.

Disentangling diversity in deliberative governance in rural Chinese villages: A RCCCL case

To dissect the nuances of deliberative governance in rural Chinese villages, we proposed three discursive dimensions of stakeholders and conflict moments in RCCCL reform from a practical perspective. In the first place, we figured out the main stakeholders in the deliberation during the land transactions and focused on those organisational and procedural settings for understanding the internal/external relations and interactions. Second, we dissected the most critical conflict moments and corresponding tactical strategies adopted for solving or mediating the main challenges; these observations are practically helpful in understanding how and why these dilemmas are handled in a (quasi-)deliberative approach, and how villagers’ preferences are transferred before and after deliberation. Third, we called for a rethinking of grassroots governance with this deliberative approach as political innovation in an authoritarian context via a power-capital nexus in both political and market domains.

Status quo of RCCCL reform in rural Chinese villages

Since authorising the implementation of relevant laws in the 13th Meeting of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee, 33 county-level regions were chosen as pilot experiments, and these have witnessed vast changes and facilitation in the usage and transfer of rural collectively-owned construction land.[6] Transactions have been carried out on more than 10,000 RCCCL parcels to date, covering more than 90,000 mu (6,000 ha) with a total investment of 25.7 billion RMB, among which 228 RCCCL parcels have been used as collateral for mortgages[7] totalling 2.86 billion RMB. Most pilot areas have evolved with the relatively well-developed policy kit for promoting RCCCL transactions, including the implementation of policy propaganda, villagers’ mobilisation, and conflict resolution.

Our case villages are located in Hongguang Town (a 40-minute drive from the centre of Chengdu). Unlike some agriculture-oriented villages, these suburban villages are located between urban and far-flung areas, and villagers no longer rely on traditional farming for their livelihood. Instead, they work in nearby cities or provide necessities for urban citizens. In 2007, an investment agreement signed by Xuyan Company and the Hongguang Town government promised the construction of a tourism project covering the three villages. To do so, these investors firstly encouraged villagers to demolish their old houses and resettle in newly-built apartments (which were not built until villagers later petitioned). According to the blueprint provided by Pidu officials, the plan of 35 m2/per person for these new apartments was much less than the per capita living space (132.29 m2) in the village’s self-constructed housing; that allowed large-scale rural residential land to be saved for profitable use. Second, land investors persuaded villagers to transfer their cultivated land by offering a higher rent (around 2,275 RMB per year) than their agricultural incomes (less than 1,000 RMB). This tempting deal facilitated the early demolition mobilisation.

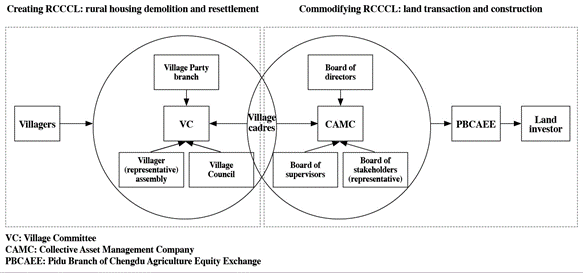

This RCCCL project was a transaction of rural residential land occupied by villagers’ houses rather than directly renting collective land. Rural collectively-owned land can generally be divided into three types (Figure 1): (1) farming land, including cultivated land, orchard land, and perennial plantations; (2) rural construction land, including RCCCL, rural residential land for rural housing, and public infrastructure and facilities (e.g., village school and hospital); and (3) undeveloped land. Land developers of the two projects were to transfer rural residential land to the RCCCL.

Figure 1. Classification of rural land-use types in China Credit: authors.

Credit: authors.

The Pidu government initiated this land transaction in the three villages of Baiyun, Hanjiang, and Koujiaba in 2007; nevertheless, this plan was interrupted due to a shortage of funds, and was subsequently continued by two subprojects of Tony’s Farm (duoli nongzhuang 多利農莊) in Baiyun Village in 2013 and Moshang Blossoming (moshang huakai 陌上花開) in Hanjiang and Koujiaba Villages in 2017. The former project of Tony’s Farm planned to profit from building and selling villas, but the blueprint stalled due to the state policy “prohibiting the building of villas and commercial houses on collective land.” The later project, Moshang Blossoming, has also been making slow progress since 2017. From 2012 to 2020, the postponement of these three projects triggered continual conflicts between villagers and developers about rent and resettlement housing issues. Our analyses also focused on such conflicts, as well as on the communicative and deliberative thinking and logic among these participants. This observation may serve as a prime example of grassroots deliberative governance in land expropriation.

Stakeholders and deliberative settings

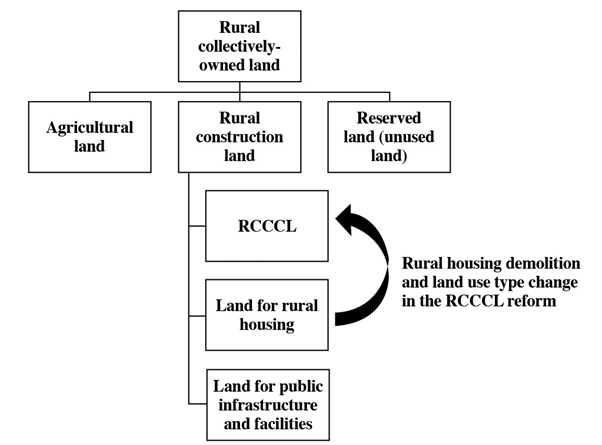

Our first focus investigates various stakeholders and their intertwined interactions in the RCCCL transaction. Generally speaking, two main types of participants are involved in influencing both the procedures and, sometimes, the decision-making (Figure 2). The first refers to those who participate directly in the land transactions and governmental administrative issues, for instance, the rural village cadres who hold both political and capital power in the VC and CAMC.[8] As the main player with regard to land issues, and with its dual administrative and economic attributes, the VC-CAMC can peacefully embed itself within a complex relationship between the government and the villagers. Such institutions also include the Pidu Branch of Chengdu Agriculture Equity Exchange (PBCAEE) mentioned below. On the one hand, they are endorsed by the government with regard to land deals, while on the other, their more flexible identities enable them to be more trusted in terms of their participation in the marketing. Villagers are another class of main stakeholder, whose land could be taken for the land deal, and who could often dominate the deliberations and negotiations before land transactions. Nevertheless, some sociopolitical changes in the last two decades – for instance the loss of the young population, the intervention of intermediaries, and the government-buy-service – have created a more complex composition of the rural village structure, and posed more obstacles to the early mobilisation of villagers’ participation and deliberation.

Figure 2. Governance in RCCCL transactions

Another important group of stakeholders are the land investors who engage in land business and undertake RCCCL projects. In most cases, these investors are not members of the villages/rural collectives, with only a small proportion being native entrepreneurs. That said, they are more likely antagonistic to local inhabitants and are driven merely by their financial interests. These investors, in most cases, have endorsements from the town(ship) government in the land deal. They work with village cadres to mobilise villagers’ participation, while also carefully handling villagers’ grievances and resistance. A rough interaction among villagers, village cadres, and investors (sometimes the town(ship) governments are involved) with their related interests maintains an equilibrium in grassroots land deals.

Indirect participants create a large external web for grassroots deliberative governance by providing technical and consultative guidance or services. First are those vertical administrative agencies that follow a process of top-down regulation making, policy implementation, and empirical experimentation. Second are the parallel market sectors: the broad market-driven forces that provide necessary services and technical support for professional questions. Third are (semi-)official management agencies such as the PBCAEE. These agencies have inextricable relationships with the town(ship) government. In such settings they facilitate a way to obtain more administrative support from higher-ups; meanwhile, as land deal brokers, they sometimes proclaim an affinity with villagers, especially in mobilising villagers’ participation and deliberating in compensation matters.

These (in)formal deliberative settings are compatible with three discursive arrangements. First are approval deliberations in the village assembly and representative assembly; these two de facto decision-making bodies can decide directly on RCCCL projects according to the latest revised Land Administration Law from early 2020, with the approval of two-thirds of villagers or villager representatives. The village Party branches (cun dangzhibu 村黨支部) and town(ship) Party branches mobilise, lobby, and agitate villager involvement in RCCCL deals. This mobilisation, based on observation of some propagandistic documents, includes tempting offers and warnings of the serious consequences of disagreeing with the land transfer. According to one notification, “We will offer generous compensation (…). [L]and transfer benefits all the villagers, and disobedience is a violation of national policies and will be dealt with in accordance with laws and regulations.”[9]

Two more deliberative settings are more informal and unstructured with regard to some interest deliberations after the confirmation of land transfer. First, the Village Council provides an arena for discussing some critical details such as compensation standards, the schedule, and the potential reconstruction project. These intra-village discussions involve a larger group of villagers, rather than only Village Committee cadres. This ensures that the RCCCL, as part of collectively-owned assets, can benefit the majority of villagers. The CAMC participates in this process by providing some professional knowledge on land transactions. The last takeaway is that since the land transactions come after demolition, individual contracts need to be signed with every household. That said, this tedious deliberative process is usually interlinked with villagers’ unreasonable demands and later resistance.

It is interesting to note that neither the VC-CAMC nor the PBCAEE mentioned below is an official institution in the full sense (although the VC-CAMC has an official background).[10] For example, the PBCAEE was spawned by a market economy (it is inextricably linked with the Pidu government, but still belongs to a relatively independent economic entity-company). This is very different from the previous government’s large-scale package for land transfer. Free economic entities can directly participate in land issues; such reform reduces some cumbersome administrative procedures and eases the tension between the higher government and the village. According to our fieldwork conducted in cities and provinces near Sichuan, such as Chongqing, Guizhou, Yunnan, and other underdeveloped regions, nongovernmental economic organisations have become increasingly active in grassroots governance.

Main conflict moments and incentives for deliberation in conflict resolution

The main conflict moments in RCCCL are focused on villager mobilisation and participation at the early stage and resistance after the land deal. In the former case, this reluctant participation has multiple causes, for example, the compensation consideration, forced demolition, and distrust of grassroots (village) cadres. For whatever reason, the village cadres and land investors have to dispel villagers’ misgivings by deliberating with them. Village cadres especially are mediating in the midst of various incentives, for example, economic considerations. They generally strive for investment for economic motivations (as well as “grey income”) and to gain political performance points for maintaining stability. Village cadres always try to limit (potential) resistance and resolve it within the village, since an ability to resolve conflicts effectively, as well as economic performance, are key criteria for their performance evaluation in Pidu.

Deliberations and compromises made in private between and among the stakeholders are almost always a better alternative than more radical petitions and redundant legal procedures. Some interviewees complained that they recognised that they could not fight against a powerful government, but as long as the compensation was acceptable, they would not take extreme action. The second moment is dealing with villagers’ resistance. When deliberative efforts failed to clinch a deal, resolving villagers’ grievances becomes a political task for grassroots cadres. In this sense, petitions are allowed only at the lower (town(ship)) level, and this privity based on a preexisting understanding between village cadres and the higher governments gives petitioners a say while also exhausting their patience through hierarchical pressure. Most often, these controllable yet accessible complaints and petitions enable a flexible problem-solving mechanism while maintaining social order.

Patient struggle: Villagers’ mobilisation and participation

Based on our observations, procedural deliberation and information disclosure commonly took place in the following stages before the land investment project in Pidu. Village group leaders first disseminated some basic information about the land project according to the village cadres’ instructions. Then, a village assembly (village representative assembly in some villages) was held, based on villagers’ preliminary understanding of the land deal. To conclude the agreements, land projects can only be launched with the voted approval of at least two-thirds of the villagers. Nevertheless, reaching an agreement was difficult in Pidu given the paradigm of “first demolition, then RCCCL transaction.”[11]

This policy is common in rural land transfers in Chinese villages, where projects are first rubber-stamped (as shown by some cases in Shandong, in Northern China), and villagers are wary of this process. Since once their dwelling is demolished, villagers have little leeway to renegotiate with the investors, they simply have to accept “good-enough” compensation. Both investors and villagers want to seize this initiative for further self-benefit. In Pidu, although the land transfer project was passed with a high vote at the VCs, only eight households signed agreements in the following month, while the majority of other villagers were waiting to seek a better deal through collective pressure on village officials and investors.

Usually, villagers protest by exercising their disapproval before voting and refusing to sign the agreement, and this collective resistance is dispelled when the deal caters to their expectations. Villagers’ conformity operates as a check and balance in negotiation with others. In some villages in Hongguang Town, after the first month of consideration, 90% of the villagers agreed in the second month, although many of them still worried about relocation. Nonetheless, a fraction of households (about 10%) still persistently disagreed with the deal, either out of nostalgia for their land, lack of professional skills to make a living, or dissatisfaction with the compensation. For whatever reason, they tried to challenge authority by petitioning and refusing to move.

The first effort was the launching of propagandistic incitement through hearsay, social media (WeChat), and informal policies by village cadres and investors in Pidu to facilitate the demolition and deal with (potential) uprisings. Most often, this top-down propaganda contained threats and sometimes intimidation, for example, listing the consequences of resistance. As an official from the urban construction office in Pidu put it, “Our policy publicity is not only carried out within and among the villagers, but also well-deliberated with the higher-ups and investors. Once villagers accepted our proposals, they must abide by this collective decision in the subsequent implementation.”[12]

Unlike political mobilisation in the Mao era,[13] current centralised decision-making in rural Chinese villages is more driven by interest incentives. As some village cadres in Pidu complained, “Decision-making after ‘democratic centralisation’ is becoming more formalised as a rubber stamp given the difficulty of mobilising and concentrating villagers for common deliberation and voting.”[14] The sociopolitical transformation of village structures and population outflow is partly to blame, while land issues in Chinese villages are always entangled with villagers’ practical considerations. Although most migrant workers in cities seem to have weak links with their home villages, they still possess land in the villages, and seldom have urban hukou (residency permits); for them, related land transactions still concern their vital interest. Hence, this perplexing land-related chaos can easily create potential uncertainties that lead villagers to petition for scrapping the previous consensus and to adopt more radical methods of self-protection.

Compromised deliberation: Dismissing villagers’ complaints and petitions

Key conflict moments after RCCCL transactions are further concerned with the compensation dwelling and rent for cultivated land. Compensation after demolition is the core deliberative issue for villagers who have lost land (or home), and for those who have no permanent dwelling after demolition other than renting apartments in the town(ship)s nearby or migrating somewhere more distant to live and work. While the resolutions provided by investors or the CAMC usually ignore the close villager-house-land linkage in rural villages, villagers who eke out a living from the land and lack professional skills always have difficulties without better alternatives. This is very true for protests and petitions caused by investors’ failure to provide the timely new apartment settlement promised before the land transaction. Resistance concerning compensation for demolition has always created potential uncertainties at the grassroots level.

How is this tension eased in a (semi-)acquaintance society?[15] (For discussions about Confucianism-based Chinese villages, for example, see Fei 2001; He and Wagenaar 2018). Very often, village cadres and sometimes village elites undertake this mediation deliberation with villagers, but such deliberations are neither the legal method nor are they deliberations in the modern democratic sense; they are more likely based on kinship through traditional communicative forms, lobbying, coercion, moral pressure, or persuasion (by family members and friends). This moral governance is sometimes more efficient than legal- and procedural-based methods. We interviewed village cadres in Hongguang who dealt with villager’s petitions resisting the land deal.

This petitioner recently rejected the land transfer agreement signed at the village assembly, and we failed in deliberating with him with extra compensation. We therefore recommended that he petitions the higher level [Pidu] (…) We warned him of the possible legal consequence of unreasonable resistance, but when the last effort fails, petitioning is allowed (petitioning is not strictly prohibited as generally thought). This compromise was based on pre-communication with the higher level for further ensuring that his petition will not reach the higher level. By doing so, he can submit his appeals and grievances to the higher level while at the same time calming down and venting his dissatisfaction in the process.[16]

This equilibrium is maintained via compromise and deliberation amongst the villagers, village cadres, and higher-ups. It benefits most from village cadres’ top-down and bottom-up mediation. This type of kinship-based relationship between and among village cadres is premised on more easily diffusing persuasive and deliberative influence in a (semi-)acquaintance society. Additionally, this interactive process is often highlighted by village cadres to produce responsible and responsive governance. For whatever reasons, village cadres are the ones who confront grassroots resistance and instability. Nevertheless, limited empowerment by the town(ship) governments constrains village cadres in fulfilling their role and ensuring that mild countermeasures are priorities in cooperation with both, as opposed to more radical approaches. Another concern is economic considerations; village cadres are core members of the CAMC director group, and some concessions for meeting demands from both sides can bring extra grey income.

The second and more sensitive topic is rent for cultivated land, which is the compensation paid to villagers who lose their farming land (except for those villagers who refuse either the renting of cultivated land or demolition). It is always tough to make decisions, especially for elderly villagers who are incapable of finding new jobs but rely upon rent for their livelihood. Once decided, the rent deal will persist for the duration of the land transaction. When land investors successfully dealt with villagers without paying the promised rent (due to funding shortfalls in this case), potential unrest built up at both the village level and in the Hongguang Township government. Usually, strong economic incentives facilitate a pre-land-reform deal. In Pidu, the investors described their post-demolition plan by saying, “First of all, the most important thing is to get the bid, and follow-up issues can be discussed gradually.” This heralded inevitable uncertainties in later policy implementation.

In 2014, villagers in Hanjiang and Koujiaba decided to petition the higher-level government because of Xuyan Company’s bankruptcy. This petition was later resolved by the town government by urging the investors to pay two months’ rent.[17] Ironically, the higher-level government, being an outsider, was not involved in this free land-market transaction, but strong administrative interventions can nevertheless force one side to change its trading practices. Although the town government claimed to protect villagers’ interests, the critical point is always whether administrative interventions that override a free land deal can cultivate a lasting property market.

Unlike the traditional top-down pressure of governance through blind suppression of villagers’ petitions, our case demonstrates that compromise deliberation for conflict resolution in land transactions is more likely based on capital accumulation incentives rather than mere political manipulation. Petitioning was allowed, but was based on preexisting compromises between the well-informed village cadres and the higher-level town(ship) government. Hierarchical political power from higher-ups exerts its influence in capital operations through the power-capital nexus, while simultaneously, this model handles and rebalances the interests of all parties, sometimes including the administrative side (mainly the village cadres and semi-official CAMC) and investors.

As we have argued, grassroots deliberations are mainly interest-based deliberations, and it is easier to mobilise villagers in deliberation over interests rather than over abstract politics. This interest-deliberation (with less political coercion) is likely to produce more dynamic interactions. These interactions and communications are mixed with the public’s own deliberative ideas and behavioural logic (a cultural influence) and are practised in formal and informal deliberative institutions. Conflicts can also be resolved in these deliberations, such as village cadres’ top-down and bottom-up mediative deliberations, and compromise deliberations between higher-level government figures and grassroots resistance. They are not just hierarchical political deliberations in the traditional sense.

What we observed is that the multi-interactions in a land transaction, whether by the government administration or in economic actions between villagers and investors, can have deliberative influences and are very likely to change the participants’ preferences and behaviour. For example, in order to reach a land transaction agreement, village cadres and investors will bargain and negotiate with villagers; the higher-level government will also deliberate with petitioners when petitioning is unavoidable and will make concessions. These interactions enable administrative and economic activities to remain relatively stable. If we embrace a broader understanding of deliberation (as many scholars such as Mansbridge et al. (2012) have endorsed in a genealogical analysis of deliberative democracy), deliberative influence can be found in many methods such as rhetoric, storytelling, protest, speech, emotion, and even silence; this understanding is by no means meant to loosely define deliberation but rather to facilitate ways of conducting deliberative politics in real life.

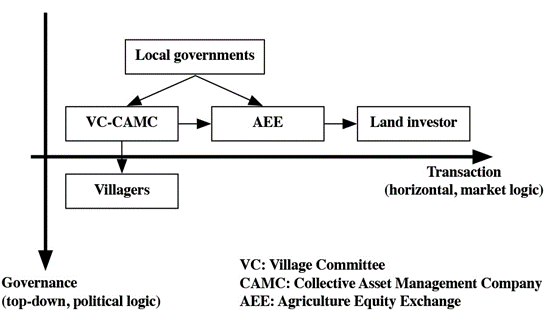

The political-capital nexus and its representative: VC-CAMC

Administrative interventions in the market economy are nothing new in China. In a governance analytical framework, this political-capital equilibrium is deliberatively maintained in complex interactions between various stakeholders in collective affairs through both vertical trickle-down political power-sharing and a horizontal capital accumulation process. It is important to understand the procedural discussions and stakeholder decision in these two-way interactions. This power-capital nexus connects both political power and capital accumulation. In our cases, it was practised through specific institutions such as the VC-CAMC, within which political deliberations and interest deliberations could be conducted simultaneously and further rebalanced in grassroots governance (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Political-capital nexus Credit: authors.

Credit: authors.

The vertical logic of this deliberative governance is a trickle-down process of political power combined with a bottom-up process of villager discussions. On the one hand, the legitimised and empowered village decision-making bodies as well as the Party-state apparatuses at all levels enact the land policies, including the RCCCL transaction and specific management bureaus, thus, for example, delving into procedural regulations and implementation, as well as the requirements for RCCCL. Both the Party-state and some management bureaus can exert additional influence on Village Committees and rural cadres indirectly. Villagers, on the other hand, are constrained outside the opaque intra-discussion, even with the village assembly and village representative assembly as deliberative venues. The capital accumulation logic in the horizontal dimension is interpreted with the market behaviour among various stakeholders. Those investors and transferers of land (village collectives/villagers) conduct transactions via intermediaries (the Agricultural Equity Exchange-capital intermediaries and the VC-CAMC political intermediaries). This political-capital nexus is intertwined with various types of deliberations from all sides and further maintains an equilibrium in grassroots governance.

More precisely, the design of the VC-CAMC as the power-capital nexus was composed of and controlled by the same group of grassroots (village) cadres in Pidu. Nevertheless, it functioned according to its role shifting. The VCs in Hanjiang, Koujiaba, and Baiyun were the core political power in the RCCCL, and village cadres in the VCs undertook the political work of propaganda and mobilisation with the town(ship) governments’ empowerment and simultaneously sustained intimate capital relationships with the land broker of AEE. On the other hand, the VC-CAMC linked both the internal (within the village) and the external (village-intermediary/AEE-investor) deliberations; in other words, pressure on both sides required the RCCCL decision-making body of the VC-CAMC to constantly rebalance both the internal and external deliberation without going to extremes.

To note, this political dimension was threefold. Firstly, hierarchical policy implementation of relocation and demolition was usually accompanied by various forms of communications such as threats, persuasion, lobbying, and deliberation. Secondly, the administrative endorsement of the higher-ups guaranteed the launch of the land project. Additionally, in terms of investors fulfilling their side of the bargain, the township government in Pidu could use its administrative power to force investors to pay compensation rather than going through the court system. Thirdly, when villager resistance (e.g., petitioning) was inevitable, the higher-level government always served as a buffer to resolve villagers’ grievances in cooperation with the frontline village cadres. Another capital line put the sometimes-antagonistic buyers and sellers at the same table through intermediaries such as the PBCAEE, balancing the two sides’ claims while also avoiding some unreasonable market behaviour. The complex role of the VC-CAMC, along with state agencies such as the PBCAEE and market forces, functioned in the midst of nuanced grassroots deliberative governance through the dual nexus of power-capital by creating a reasonably inclusive and equally deliberative space. In a nutshell, money and politics were deliberatively equilibrated in the interactions among these stakeholders.

Such a mechanism, which we describe as a “deliberative equilibrium,” indicates how grassroots stability and social (villager) resistance are rebalanced through multi-interaction and deliberation, how interests are redistributed after this type of deliberation, and how this deliberative governance facilitates good governance in the long run. In such a toolbox, politics (administration) and capital can have a reciprocal relationship. For example, a top-down administration can guarantee a relatively safe land transaction between villagers and investors, while at the same time safeguarding villagers’ interests by forcing investors to fulfil their responsibilities, as well as dealing with villagers’ resistance in a peaceful way. The capital dimension says more about how all participants work together for the benefit of all without going to extremes. All these activities are regulated in seemingly standardised deliberative intuitions such as the VC-CAMC, within which modern deliberative procedures and traditional norms work together and further contribute to the modernisation of China’s (deliberative) governance.

Conclusions

Mainstream Anglo-American studies of deliberation or deliberative democracy have persistently focused on reason and common good. However, in our analytical framework, we reconstruct a paradoxical interlinkage between deliberation and authoritarianism in Chinese grassroots governance. These efforts, however, are not an attempt to loosely define a conceptual understanding of deliberation, but rather to expand ideas of deliberation to a broader acknowledgement of various communicative forms such as persuasion, rhetoric, and even coercion, and destinations where deliberation should end. In this sense, a more down-to-earth and inclusive deliberation should be the aim of further research by students in this field. There may be doubts about the democratisation of the Chinese regime, but the autonomous grassroots (the villages) nevertheless provide a proper locus for authentic deliberation and deliberative-like influence.

Our second effort is to disentangle a more vibrant grassroots deliberative governance-based equilibrium by introducing the case of land transactions. Unlike traditional state-controlled and government-led deliberation, grassroots governance indicates another deliberation image, in which the participants interests’ (the villagers, village cadres, investors, and sometimes higher-level government), social stability, and political power-sharing are all kept in equilibrium through interactions between them. Indeed, this intertwining of power and capital allows more leeway for deliberation. In the best conditions, all parties can gain a relatively satisfactory response through such deliberation. Even if there are (potential) uncertainties, they can also be dealt with by mediation and compromise deliberations. Since maintaining stability is still the top priority in grassroots governance, this deliberative equilibrium can fulfil its role in this toolbox for further facilitating policy implementation.

This pragmatic-based deliberation, as many authors are convinced, does facilitate good (grassroots) governance. As indicated in the cases above, these interactions are far more than mere hierarchical (in a top-down sense) and pressure-orientated deliberations; they are intertwined with more interactive and communicative forms for their function. If stable and responsive governance is regarded as a criterion of “good governance” in the Chinese context, then a deliberative equilibrium constitutes an important part of this toolbox. Moreover, this equilibrium further describes a very dynamic process of administrative and economic interaction, and this takeaway may contribute to a pluralistic understanding of deliberative democracy in different contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the reviewers’ critical comments and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Manuscript received on 30 June 2021. Accepted on 22 June 2022.

References

AUSTEN-SMITH, David, and Timothy J. FEDDERSEN. 2008. “In Response to Jurg Steiner’s ‘Concept Stretching: The Case of Deliberation.’” European Political Science 7(2): 191-3.

BÄCHTIGER, André, John S. DRYZEK, Jane MANSBRIDGE, and Mark WARREN (eds.). 2018. The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

BESSETTE, Joseph M. 1997. The Mild Voice of Reason: Deliberative Democracy and American National Government. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

BOHMAN, James. 1998. “Survey Article: The Coming of Age of Deliberative Democracy.” Journal of Political Philosophy 6(4): 400-25.

CHAMBERS, Simone. 2003. “Deliberative Democratic Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 6(1): 307-26.

CHEN, Jidong, and Yiqing XU. 2017. “Why do Authoritarian Regimes Allow Citizens to Voice Opinions Publicly?” The Journal of Politics 79(3): 792-803.

COLLIER, David, and Steven LEVITSKY. 1997. “Democracy with Adjectives: Conceptual Innovation in Comparative Research.” World Politics 49(3): 430-51.

DIAMOND, Larry. 2015. “Facing Up to the Democratic Recession.” Journal of Democracy 26(1): 141-55.

DRYZEK, John S. 2009. “Democratization as Deliberative Capacity Building.” Comparative Political Studies 42(11): 1379-402.

FEI, Xiaotong. 2001. Plurality and Unity in the Configuration of the Chinese People. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

HABERMAS, Jürgen. 1983. Interpretive Social Science vs. Hermeneuticism: Social Science as Moral Inquiry. New York: Columbia University Press.

HE, Baogang. 2006. “Western Theories of Deliberative Democracy and the Chinese Practice of Complex Deliberative Governance.” In Ethan LEIB, and Baogang HE (eds.), The Search for Deliberative Democracy in China. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 133-48.

———. 2014. “Deliberative Culture and Politics: The Persistence of Authoritarian Deliberation in China.” Political Theory 42(1): 58-81.

———. 2019. “Orderly Political Participation in China.” In Jianxing YU, and Sujian GUO (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Local Governance in Contemporary China. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 347-63.

HE, Baogang, and Hendrik WAGENAAR. 2018. “Authoritarian Deliberation Revisited.” Japanese Journal of Political Science 19(4): 622-9.

HE, Baogang, and Mark E. WARREN. 2017. “Authoritarian Deliberation in China.” Daedalus 146: 155-66.

LANDWEHR, Claudia. 2015. “Democratic Meta‐deliberation: Towards Reflective Institutional Design.” Political Studies 63: 38-54.

LYON, Arabella. 2004. “Confucian Silence and Remonstration: A Basis for Deliberation?” In Carol S. LIPSON, and Roberta A. BINKLEY (eds.), Rhetoric Before and Beyond the Greeks. New York: State University of New York Press. 131-45.

MANSBRIDGE, Jane. 2007. “‘Deliberative Democracy’ or ‘Democratic Deliberation?’” In Shawn W. ROSENBERG (ed.), Deliberation, Participation and Democracy: Can the People Govern? London: Palgrave Macmillan. 251-71.

MANSBRIDGE, Jane, James BOHMAN, Simone CHAMBERS, Thomas CHRISTIANO, Archon FUNG, John PARKINSON, Dennis F. THOMPSON, and Mark E. WARREN. 2012. “A Systemic Approach to Deliberative Democracy.” In John PARKINSON, and Jane MANSBRIDGE (eds.), Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy at the Large Scale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1-33.

MILL, John Stuart. 1975. Three Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

PLATTNER, Marc F. 2015. “Is Democracy in Decline?” Journal of Democracy 26(1): 5-10.

REHG, William, and James BOHMAN. 1996. “Discourse and Democracy: The Formal and Informal Bases of Legitimacy in Habermas’ Faktizität und Geltung.” Journal of Political Philosophy 4(1): 79-99.

ROSENBERG, Shawn W. 2007. “Types of Discourse and the Democracy of Deliberation.” In Shawn W. ROSENBERG, Deliberation, Participation and Democracy: Can the People Govern? London: Palgrave Macmillan. 130-58.

SARTORI, Giovanni. 1970. “Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics.” American Political Science Review 64(4): 1033-53.

STEINER, Jürg. 2008. “Concept Stretching: The Case of Deliberation.” European Political Science 7(2): 186-90.

TANG, Beibei. 2015a. “Deliberating Governance in Chinese Urban Communities.” The China Journal 73: 84-107.

———. 2015b. “The Discursive Turn: Deliberative Governance in China’s Urbanized Villages.” Journal of Contemporary China 24(91): 137-57.

XIA, Zhiping 夏支平, and ZHANG Bo 張波. 2010. “熟人社會還是半熟人社會: 轉型期自然村性質的再探討” (Shuren shehui haishi ban shuren shehui: Zhuanxing qi zirancun xingzhi de zai tantao, An Acquaintance Society or a Semi-acquaintance Society: A Re-examination of the Nature of Village in Transition). Yulin shifan xueyuan xuebao (玉林師範學院學報) 31(4): 60-4.

YANG, Renhao, and Qingyuan YANG. 2021. “Restructuring the State: Policy Transition of Construction Land Supply in Urban and Rural China.” Land 10(1): 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010015

YU, Keping. 2011. “Good Governance and Legitimacy.” In Zhenglai DENG, and Sujian GUO (eds.), China’s Search for Good Governance. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 15-21.

ZUO, Jiping, and Robert D. BENFORD. 1995. “Mobilization Processes and the 1989 Chinese Democracy Movement.” Sociological Quarterly 36(1): 131-56.

[1] See the debate between Jürg Steiner (2008) and David Austen-Smith and Timothy J. Feddersen (2008).

[2] The concept of authoritarian deliberation proposed by He Baogang and Mark E. Warren (2017) is more likely to distinguish how a Chinese case (deliberation in authoritarianism) could be different from a Western one. He and Warren rightly expand the frontier of deliberative democracy studies into more plural forms. Nevertheless, our analyses favour relating Chinese practices back to a more general idea of deliberative democracy, by seeking some common ground between the two.

[3] According to Dryzek (2009), lacking electoral or constitutional terms in authoritarian regimes, officials with a background in deliberative public space or strong willingness to carry out deliberative governance are more easily accepted by the public and avoid the impact of elections.

[4] Given that a possible deliberation could only exist in China’s grassroot rather than at the authoritarian regime level, previous studies prefer an analysis outside formal political organisations in China. See for example Tang (2015a, 2015b).

[5] These three villages are geographically adjacent; they are located in southwestern Sichuan, and are structurally consistent in political and sociological terms. Like many other midwestern villages we have observed, the village Party secretary in these villages also concurrently serves as the village head (yijiantiao 一肩挑), which facilitates both the connection and top-down surveillance between the village and the higher-level government at the same time. As for the leadership team, the village head in Baiyun Village has a higher level of education (university degree); he is more willing to embrace emerging governance methods (deliberative governance) and more timely handling of villagers’ resistances.

[6]全國人民代表大會常務委員會關於授權國務院在北京市大興區等三十三個試點縣(市, 區)行政區域暫時調整實施有關法律規定的決定 (Quanguo renmin daibiao dahui changwu weiyuanhui guanyu shouquan guowuyuan zai Beijing shi Daxing qu deng sanshisan ge shidianxian (shi, qu) xingzheng quyu zanshi tiaozheng shishi youguan falü guiding de jueding, Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on authorising the State Council to provisionally adjust the implementation of the provisions of relevant laws in the administrative regions of 33 counties (cities and districts) under the pilot program including Daxing District in Beijing Municipality).

[7] The RCCCL can use land use rights as collateral for applying for bank loans, this being a new measure in grassroots land reform that is intended to enhance the feasibility and legitimacy of land circulation.

[8]The CAMC is a special institution established to run collectively-owned assets managed by Village Committees with three configurations: a shareholder representative board, a directors’ board, and a supervisory board. Commonly, the VC is responsible for the final land transaction decision-making, while the CMAC takes charge of the implementation of concrete policies, demolition compensation, villager resettlement, and so on. But it should be noted that village cadres are the main stakeholders in both the VC and the CAMC at the same time. See more at http://gk.chengdu.gov.cn/govInfoPub/detail.action?id=1630178&tn=2 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

[9] A notice posted in the village’s WeChat group.

[10] The VC-CAMC and PBCAEE are two very substantive operating agencies in the village collective economy. These entities, although themselves regulated by local administrative regulations (the local government does not intervene directly in their land business), operate in market economy conditions like other enterprises. In fact, such in-between institutions are quite commonly seen in Chinese localities. For more details see http://gk.chengdu.gov.cn/govInfoPub/detail.action?id=1630178&tn=2 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

[11] As the RCCCL indicates, land investors can carry out building demolition and project construction before site selection, reconstruction, compensation, and other related issues, which is precisely the problem that villagers worry about.

[12] Official in the Urban Construction Office in Hongguang Town, interviewed by the authors, Chengdu, 6 July 2020.

[13] For more descriptions of political mobilisation in the Mao era, see Zuo and Benford (1995).

[14] Village cadre in Hongguang, interview by the authors, Chengdu, 9 September 2020.

[15] The famous formulation of “acquaintance society” by Fei (2001) for describing close kinship-based village society is now eroded by a higher-level of modernisation, especially in the eastern coastal villages, for instance with emerging administrative villages (villages formed after demolition, resettlement, etc.). Thus, Xia and Zhang (2010) have reexamined this view by proposing a more feasible model of semi-acquaintance society to account for this change. Nevertheless, the deconstruction of traditional rural culture is far more irreconcilable. To date, the (semi-)acquaintance society-based deliberation within Confucian culture and tradition naturally gives rise to informal deliberations. According to those village cadres, “means of compromise for further dealing with trouble-makers are sometimes reluctant action, within which village cadres and elites play the role of peacemaker” (ibid: 61).

[16] Cadre of Hanjiang Village, interview by the authors, Chengdu, 10 July 2019.

[17] The Pidu government used an administrative order (red-letterhead document) to require investors to pay compensation instead of legal methods.