BOOK REVIEWS

Social Networks and Ethnonational Hinges in Hong Kong: A Relational Approach to Ethnonational Identification

Anson Au is Assistant Professor of sociology at the Department of Applied Social Sciences at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong (anson-ch.au@polyu.edu.hk).

Introduction

The empirical and theoretical study of ethnic identity in Hong Kong rests firmly on an enduring conceptualisation of a binary opposition, depicted as a kind of localist identity, juxtaposed against a staunchly Chinese nationalist identification (Ma and Fung 1999; Mathews, Ma, and Lui 2008).

The historical beginnings of this binary opposition are well-documented. From the 1970s onward, Hong Kong locals began identifying themselves based on perceived distance from the Mainland, amid popular constructions of Hong Kong as a modern, “forward” society emancipated from the “backward” Mainland (Ma E. 1999). Reflecting on city-wide surveys of ethnic identification from 1996 to 2006, Ma and Fung remark: “the greater the distance between Hong Kong people’s self-image and their image of Chinese, the stronger their sense of belonging to the localized culture of Hong Kong became” (2007: 173). Similarly, several case studies have descriptively shown that the rhetorical frames adopted by social movements articulate an indigenous Hongkonger identity as distinct from associations with a Chinese identity (Ma N. 2011; Ng and Lai 2011; Veg 2016; Fong 2020).

Simultaneously, a loosely bound literature on cultural identity has problematised the conceptualisation of a binary opposition. Fung (2004) argues that the Hongkonger ethnic identity is a “hybridised” one, neatly situated between “Hong Kong” and traditional “Chinese” and evinced by the birth of more nuanced identity categories in public opinion polls over the years, such as “Hongkonger in China”[1] (Lee S. Y. 2020). Veg (2017) also suggests there may be nuances in the evolution of ethnic identity in Hong Kong that have been glossed over, disaggregating layers of a Hongkonger ethnic identity that he argues is informed by different political and civic values.

This article advances this debate by adopting as its launching point Andreas Wimmer’s emphasis that the empirical and analytical questions raised by contentious ethnic identities and relations “cannot be solved by definitional ontology – by trying to find out what ethnicity ‘really is’” (2008: 294). That is, predetermining the meanings of ethnicity places a stranglehold on how we think of its social construction, overlooking the processes through which identities overlap and co-construct one another (Calhoun 1994; Sanders 2002; Chai 2005). Indeed, despite claims that vindicate and problematise an apparent binary opposition between Hongkonger and Chinese (ethnic and civic) identities, little has been done to empirically examine how these identities themselves are related on a city-wide scale. Though city-wide surveys have been conducted (Chan and Fung 2018; Steinhardt, Li, and Jiang 2018; Lee and Chan 2022), these studies largely trace the rise of the Hongkonger identity through demographic correlates. In assuming that one identity rises at the expense of the other, they implicitly accept their binary conceptualisation.

Taking this as a point of departure, this article directly analyses the relations between fine-grained identifications as Hongkonger and as Chinese, among other identities, using 2019 city-wide representative survey data on ethnic identifications. Adopting a processual approach to understanding ethnonational identity construction in Hong Kong, this article develops a novel set of identity indices and examines how varying (ethnic and civic) identifications affect respondents’ identifications as a Hongkonger. Connections drawn between the variables are further rationalised with interpretive accounts of identity-making from qualitative interviews. This article advances the concept of ethnonational hinges through which individuals are theorised to switch between a civic Hongkonger identity to appease nonfamilial ties and a pan-Chinese racial identity to appease familial ties, buttressed by deliberate and automatic forms of cognition that mandate conformity to a larger social unit. This article concludes with a discussion of the relational picture of the porous social bases of ethnonational identification in Hong Kong that defy essentialist depictions of a simple Hongkonger-Chinese binary.

Theorising ethnonational identification

Problematising the Hongkonger-Chinese binary

What makes a Hongkonger? Much scholarship on the Hongkonger identity, fixed on a binary opposition, has proposed that the degree to which individuals feel de-sinicised or anti-Sinoist is what defines the Hongkonger identity (Chiu and Kwan 2016; Veg 2017; Chan and Fung 2018). The 2019 protests that erupted in Hong Kong in response to a proposed extradition bill between the city and Mainland China further inflamed ethnic tensions in Hong Kong and fuelled academic conceptualisations of the Hongkonger identity as anti-Sinoist (Chung 2020; Lee S. Y. 2020). This event was perceived as a tension between the state and civil society (reflected among emergent discussions about them within families) that led to falling institutional trust in Hong Kong, and ultimately a rise in anti-Sinoist rhetoric in mainstream electoral politics (Ma N. 2011; Ip 2015, 2020; Steinhardt, Li, and Jiang 2018; Wong, Khiatani, and Chui 2019; Chow, Fu, and Ng 2020; Shek 2020; Chui, Khiatani, and Ip 2022).

This dichotomous conceptualisation of the Hongkonger identity filtered through into recent depictions of occupation and age as grounds for enacting this binary. This includes young students who have been popularly conceived as supporters of pro-independence social movements in Hong Kong (Veg 2016). As Ku (2020) observes, young students constituted a politically vibrant and vocal group in opposition to the extradition bill, leveraging new social media platforms such as Telegram, Twitter, and LIHKG (an anonymised blogging platform similar to Reddit, focused on Hong Kong affairs).

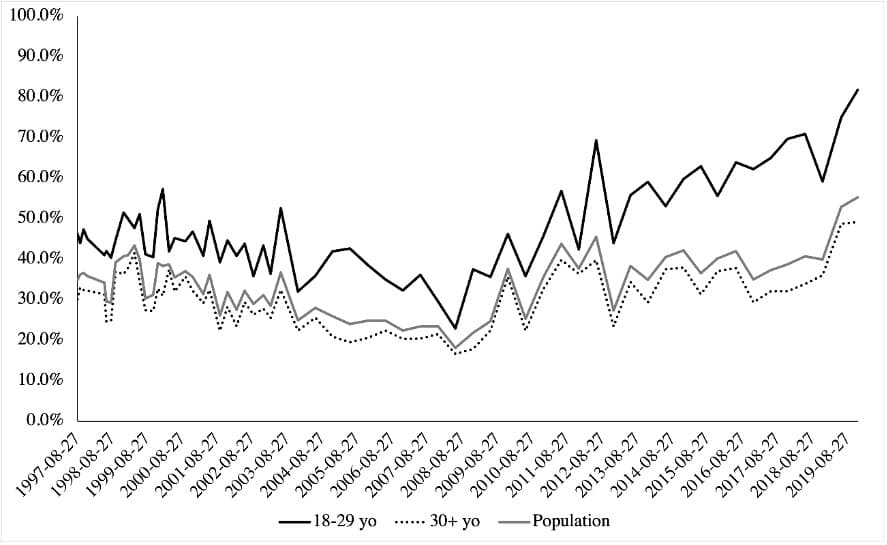

Figure 1. Identification as a Hongkonger (not Chinese)

Source: Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute.

A first glance at ethnic identification by age group appears to lend some support to this idea. Figure 1 presents preliminary data on the percentage of respondents who identify as a Hongkonger (not Chinese) in the period from the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to the People’s Republic of China until 2019, when the antiestablishment sentiments were the highest during citywide protests that swept headlines around the world. Identification as a Hongkonger among youth (aged 18 to 29) has always been higher than in the general population, but this difference has widened most in recent years, with 80% of youth choosing this identification (they were about 45% in 1997), compared to 49% of people aged 30 or older and 55% of the general population (Wong, Khiatani, and Chui 2019; Shek 2020).

Generational change and attendant shifts in values appear to lend credence to socialisation as an explanation for age and occupations being correlated to Hongkonger identification, particularly as younger individuals grow more likely to favour postmaterialist and liberal values (Kiley and Vaisey 2020). However, these accounts of the Hongkonger ethnonational identity as anchored in occupations, age groups, and even anti-Sinoist values are part and parcel of the prevailing essentialist paradigm concerning ethnonationalism (Lamont 2014). While potentially important for predicting individual psychological proclivities, these accounts evoke socialisation as an argument for a priori criteria for ethnic identifications but suffer serious theoretical limitations.

For one, empirical evidence on value shifts in China has been inconclusive and even deviant from the correlation between younger generations and liberal values typical of Western nations (Zhang, Brym, and Andersen 2017). Furthermore, as Siu-yau Lee (2020) argues in his own survey study of Hong Kong ethnic identity, socialisation based on generational differences does not account for variation among individuals with demographic similarities. Recent evidence adds to this complexity by showing that individuals’ choice of ethnic identification in the city oscillates when triggered by sporadic and evocative events, such as Legislative Council elections or demonstrations (Lee and Chan 2022). On the limitations of socialisation as inherently preoccupied with individual psychological proclivities, Swidler (2001) classically asserts that it fails to provide a sustainable account of the cultural process of ethnonational identification because it neglects its relationality. Actors build meanings about ethnonational categories not from their individual biographical details or psychological profiles, but by drawing from a repertoire of symbols, rituals, and worldviews that are relational and cultural. The causal significance of culture, moreover, is not in defining ends of significance, but in providing cultural components (symbols, rituals, worldviews) used to construct strategies of action such as ethnonational identification (Swidler 2001).

This is why (i) values such as anti-Sinoism are an insufficient explanation for identification, and (ii) meaning-making about ethnonational identities will often lead to contradictory meanings (of what it means to be a Hongkonger) that fall beyond the explanatory realm of an essentialist account of ethnicity. By way of (i), values do not explain why one individual adopts one identification versus another because values at best provide rationales for predetermined ends, but not scripts to adjudicate the appropriate course of action or thought (Swidler 2001: 86-7; Kaufman 2004: 340). Moreover, such scripts are not individual but rather relational in nature because they are learned from rituals and meanings shared by others in the same social setting (DiMaggio 1997).

This is why meaning-making itself, including the formation of values, is a contradictory process. Ethnic identifications as a cultural process are a sphere of practical activity. They group together symbols whose meanings themselves are contradictory, contested by people in different positions, loosely integrated across variegated spheres of activity into a whole, and subject to constant change (Goldstein and Stecklov 2016; Wallace 2017). An important illustration of the contradictory nature of ethnonational meaning-making, as Wuthnow (2018) recounts, is when people themselves do not understand their own meaning-making and their classifications of ethnonational identifications are not stable in a structuralist sense. Put simply, conceiving of the Hongkonger identity as a binary against a Chinese identity and based on anti-Sinoist values is an essentialist account of identification that theoretically straitjackets our understanding of the micro-cultural processes that inform said identification by denying their relationality.

A relational approach to ethnonational identification

In contrast to an essentialist account of ethnicity, this article theorises ethnonational identification as a porous and relational process. A relational approach of determining ethnonational groupness insists on recognising the inductiveness of individual self-identifications as the analytical objective, rather than predetermining the categories that individuals might use (Wimmer 2008, 2013). Individuals filter themselves into ethnonational group classifications using taken-for-granted schemas that are available to them from national cultural repertoires that surround them (Lamont and Thévenot 2000).

In The Dignity of Working Men (2000), Lamont adopted a similar approach to induction by uncovering who and how professionals felt superior and inferior to and different or similar to. Her inquiry unearthed not only the topography of the ethnonational lines that cleaved groups apart, but the criteria each used to draw distinctions from others. More importantly, these criteria were found to draw from multiple sources of meaning that spanned a range of “social phenomena, institutions, and locations” (Lamont and Molnár 2002: 169) and “social and collective identity, class, ethnic/racial and gender/sexual inequality, professions, science and knowledge and community, national identities and spatial boundaries” (Lamont 2014: 815). Indeed, as Ho (2022) finds in a topic modelling of constructions of Hong Kong nationalism, discourses about what it means to be a Hongkonger bleed across traditional demographic lines. Chew (2022) corroborates this account in interviews of offline settings in Hong Kong restaurants, finding that ethnoracial boundaries are performed in spaces where minorities are workers. Their performances are what Chew calls symbolic labour to reimagine the hierarchy of race and ethnicity, and even gain status by remoulding it.

This is consistent with Lamont, Beljean, and Clair’s theorisation that racial hierarchies are rigid in institutionalised structures, such as with the unequal distribution of material resources in the labour market, but plastic on the micro-level. Ethnonational identification and rationalisation comprise micro-cultural processes that are “centrally constituted at the level of meaning-making” (2014: 815) but draw upon the coordination of action under shared cognitive frameworks through which individuals perceive and make sense of their environment (Cerulo 2010; Lizardo 2021).

The point, therefore, is not that existing accounts of ethnonational identity have erred in identifying master categories of criteria for self-identification, but that the predetermination of identification criteria for such self-identification, of which a binary is a part, is a problem. In answering the call for a “general sociology of the properties and mechanisms of boundary processes, including how these are more fluid, policed, crossable, movable, and so on” (Lamont 2014: 815), this article demonstrates that ethnonational identification is a cultural process that is not contingent on dichotomous outcomes in constructions of an ethnonational Hongkonger identity.

The cultural history between Hong Kong and the Mainland lends well to a porous and relational conceptualisation of identification. The move to binarise the Hong Kong identification vis-à-vis the Mainland has been a recent phenomenon that largely kickstarted in the 2010s (Ip 2015, 2020; Veg 2017). The decades prior to this generally recognised the ties between Hong Kong families and their ancestral Chinese heritage (Mathews, Ma, and Lui 2008), although the Hongkonger-Chinese identification was still binary because Hong Kong was believed to represent advanced economic development compared to low economic development in the Mainland. Nonetheless, the fact that the social bases of this can shift (from developmental concerns in the pre-2010s to political ones in 2010s onward) suggests that identification is relational in nature.

Ethnonational hinges

This article advances the concept of ethnonational hinges through which individuals make ethnonational identifications. The concept of ethnonational hinges builds upon Maghbouleh’s concept of racial hinges that “open or close the door to whiteness as necessary” (2017: 5). Focusing on Iranians in twentieth century America, Maghbouleh observed a roster of legal cases in which Iranian minorities were inconsistently classified by courts as white in some cases and non-white in others. These variations in classification, she contends, became symbolic hinges through which subsequent Iranian claimants would vacillate between identifying with “clearly white” Iranians and distancing themselves from whiteness to legitimate their claims. The inconsistencies in Iranian ethnic identification determined by courts inadvertently offered Iranians the ability to shift their identity between white and non-white for instrumental gain.

Building upon this premise, this article theorises that individuals are not only subjects, but agents who shape and use ethnonational hinges. Ethnonational hinges draw attention to the micro-level, everyday contexts from which individuals draw meaning. As Abrutyn and Lizardo observe, relying on external forces such as values (e.g., anti-Sinoism) to explain action often “fall[s] flat when scrutinized by modern brain science, as distal causes do not appear to move the dial for mobilizing action (…). Instead, the proximate nature of rewards causes role-based behavior to occur” (2023: 205).

This article focuses on one particular proximate social space and prism through which contexts inform their identification: social networks. The density of Chinese social networks makes them an especially poignant space where the activation of cultural resources is visible to all actors and, by extension, encourages isomorphism in claims-making to identities. In China, social networks are the lifeblood of social and economic transactions as all interactions and relations are engrained in a traditional networking culture (guanxi 關係), that replete with rules that mandate reciprocity (renqing 人情) in the exchange of favours and value conformity (Bian and Ikeda 2018; Au 2022). Attaining an upkeep of reciprocity is key to sustaining the strength of a relationship (ganqing 感情), which in turn is moralised as the measure of one’s personal reputation (mianzi 面子) in their networks (Barbalet 2021).

The close coupling of network reputation and network performance is a significant driver of identity-making. Cultural resources and identities, such as being gay, being a fan of foreign music, and being a consumer of symbolically significant, high-status goods, are all “latent ways for members of peer groups and workplaces to evaluate the worthiness of their counterparts (…) such that an improved reputation has accordingly been linked to [occupational success and social attractiveness] and, conversely, a poorly evaluated identity (…) can serve as the basis of discrimination” (Au 2023: 77; see also Dickens, Womack, and Dimes 2019).

Thus, the embeddedness of contacts across social spaces (different workplaces and peer groups) into concentrated, dense networks forms the basis of the multiple rewards that motivate role performance (Abrutyn and Lizardo 2023). Like Iranians who make competing claims to both whiteness and non-whiteness to their personal advantage (Maghbouleh 2017), I theorise that Hong Kong individuals respond to simmering ethnonational tensions that appear to distance locals from Mainlanders (Veg 2016; Ku 2020) by conceptualising two separate ethnonational identities conjoined by a symbolic hinge: (1) a Hongkonger (civic) identity and (2) a pan-Chinese (racial) identity.

Individuals draw from everyday political realities in constructing (1) a Hongkonger civic identity to appease nonfamilial ties. Ethnic categorisation as a cultural process is subsumed into civic conflicts, leading to malleable identities that shift across time and space. In a study on state racialisation in Israel/Palestine, for instance, Abu-Laban and Bakan (2008) examine the unfolding of Charles Mills’ Racial Contract (1997) in Israel: they delineate a cultural assignment of an ethnic non-identity to Palestinians by the state, and by contrast, a conflation of Judaism (a religio-cultural set of ideals) with Zionism (a political ideology) in the ethnic identity construction of Israelis. In Hong Kong, ethnonational identity is similarly subsumed into civic disagreements born out of ongoing political events. The case of the 2019 unrest is a useful example. As Figure 1 demonstrates, the unrest kickstarted an uptick of identification as a “Hongkonger” in contradistinction from (Mainland) Chinese. Widely circulated in print and social media in Hong Kong and abroad with escalating incidents of police-protester conflicts on the ground, the unrest grew pervasive in Hong Kong society (Lee F. 2020). It is here that occupational roles influence this ethnonational civic identity: students and professionals are most strongly associated with this identity, because they were the most politically engaged in the 2019 unrest in conjunction with peers who attended (Ku 2020).

However, individuals also balance this civic identity with the other end of the ethnonational hinge, namely, to construct (2) a common Chinese racial identity to appease familial ties. Though not captured in many surveys on identification, familial networks are a separate social space from their occupations and peer or age groups, and exert a powerful influence on the cultural biases that they adopt. The family is moralised in Chinese networks as the primordial social unit towards which all relations are oriented. Confucianist notions of filial piety are filtered through networks to valorise obligations to familial ties (Barbalet 2021). As Miles and Vaisey (2015) find through surveys about moral dilemmas and decisions, the cultural biases (replete schemas and scripts) that people form as a result of family structure are distinct from and even more influential than those formed by occupations, peer groups, and age groups. The family is thus connected to individuals’ willingness to identify by separatist ethnic terms and, in response, to foreground race in their constructions of ethnonational identity. This gains credence from recent survey studies of Hong Kong families that find that while peer influence and media consumption were positively correlated with radical intentions in the 2019 unrest, family discussions about politics were associated with an opposite effect (Chui, Khiatani, and Ip 2022).

The immediacy of the two network segments in everyday life (peer groups and families) drives individuals to “inherit from the social environment[s] (…) a set of heuristics, hunches and shallow (but useful because they work most of the time) practical skills that allow persons to best interface externalized structures, contexts and institutions” (Lizardo and Strand 2010: 206). This set of heuristics and skills, namely, conformity-seeking in Chinese social networks, is indicative of the forms of cognitive associations through which the two identities and their interlocking hinge take shape.

For (1) the Hongkonger civic identity, overt political participation reflects a form of deliberate and rule-based reasoning that renders ethnicity a ground on which to draw national lines. Individuals expend considerable amounts of time pondering choices about the most ideal ways to signpost solidarity with politically active friends and present their selves in amicable fashion; that is, a Hongkonger civic identity is earned through performances of loyalty.

For (2) the pan-Chinese racial identity inspired by familial obligations, by contrast, identity-making draws upon cultural stores that are automatically more than deliberately activated. The moral significance of family is externally scaffolded in institutions such as the media and education that render familial obligations a readily available cultural code and an orderly behavioural pattern. A pan-Chinese racial identity, therefore, is not earned, but inherited, as if by heavenly mandate. The significance of this sense of obligation to family above all else, pervasive in Chinese society, accounts for why individuals treat this action as an “internalized detailed, highly structured cognitive and normative template” (ibid.).

The ideation of these two interlocked identities, therefore, is bulwarked by both conscious (deliberate) and unconscious (automatic) cognitive associations that stretch across racial and ethnic boundaries – as well as fluid switches across their interlocking ethnonational hinge to preserve these dual identities and appease actors in dislocated parts of their social networks. On multiple levels, then, individuals are motivated to “switch” their identifications across ethnonational hinges to appease their reference groups by conforming their identity-making and to bolster their network reputation among contacts from work, family, peer groups, and other domains at once – and because, on a fundamental level, doing so “just feels right.” Just as Bourdieu’s respondents in Distinction (1979) “just see” what good art is, individuals formed unconscious, schematic habits of interpretation about the moral worth of conformity that guide action and inform social scripts (Miles and Vaisey 2015).

Methodology

Survey data and analysis

The representative dataset analysed comes from a city-wide survey, “2019 Hong Kong People’s Ethnic Identity survey”, conducted by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (formerly the Public Opinion Programme) at the University of Hong Kong. The target population of the survey was Cantonese-speaking adults in Hong Kong aged 18 or above. The sample was weighted according to the gender and age distribution of the population of Hong Kong. The survey was conducted at the end of 2019, in December, after the brunt of the demonstrations that rocked the city months prior.

Questionnaires were conducted by interviewers through randomly generated telephone numbers, based on prefixes provided by the Office of the Communications Authority. Invalid numbers were eliminated according to dialling records to produce the final sample (N = 1,001). Following successful contact with households, one member was selected for an interview using the “next birthday” rule to efficiently produce a sample that represents the household (O’Rourke and Blair 1983).

The dataset includes a novel set of indices for directly gauging respondents’ ethnic identification. These are called the identity index of being: (1) a Hongkonger (Hoeng gong jan 香港人), (2) a Chinese citizen (Zung gwok jan 中國人), (3) a citizen of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) (Zung waa jan man gung wo gwok gung man 中華人民共和國公民), (4) a member of the Chinese race (Waa jan 華人), (5) an Asian (Ngaa zau jan 亞洲人), and (6) a global citizen (sai gaai gwok man 世界國民). Each index is scaled out of 100 and calculated with questions posed to respondents about the strength and importance of a given identity, rated from 1 to 10. These indices parse out and gauge the multiple and complex ways in which respondents create their ethnic identities from ideations of race, ethnicity, culture, and citizenship at multiple geographical levels (Hong Kong, China, Asia, and the globe). Understanding the relationships between them therefore offers an insightful vista into the boundaries and processes that prefigure respondents’ ideations of what a Hongkonger identity is – and how strongly they identify with it.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of all variables analysed

| Percentage | Mean | Standard deviation | ||||

| Identity index | ||||||

| Identity index of being a Hongkonger | 83.03 | 20.51 | ||||

| Identity index of being a Chinese citizen | 66.60 | 30.86 | ||||

| Identity index of being a citizen of the PRC | 56.33 | 32.76 | ||||

| Identity index of being a member of the Chinese race | 68.00 | 31.07 | ||||

| Identity index of being an Asian | 74.14 | 22.51 | ||||

| Identity index of being a global citizen | 63.52 | 26.15 | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| Primary or below | 19.8 | |||||

| Secondary | 47.4 | |||||

| Tertiary or above | 32.8 | |||||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Administrative and professional worker | 31.7 | |||||

| Civil and service staff | 21.1 | |||||

| Labourer | 8.3 | |||||

| Student | 4.8 | |||||

| Homemaker | 10.4 | |||||

| Other | 23.7 | |||||

| Place of birth | ||||||

| Hong Kong | 67.9 | |||||

| Mainland China | 30.0 | |||||

| Other | 2.1 | |||||

| Family class | ||||||

| Lower class (<HKD 9,500/month) | 32.5 | |||||

| Middle class (HKD 9,500-55,000/month) | 35.7 | |||||

| Upper class (>HKD 55,000/month) | 31.8 | |||||

| Age | ||||||

| 18-29 years | 17.6 | |||||

| 30-49 years | 34.1 | |||||

| 50-69 years | 35.5 | |||||

| 70 years or above | 12.8 | |||||

Source: author.

The dependent variable was the identity index score of being a Hongkonger, which offered a direct measurement of the strength and importance of a Hongkonger identity.

A factor analysis was conducted on the five remaining identity indices of being a Chinese citizen, a citizen of the PRC, a member of the Chinese race, an Asian, and a global citizen. Factor analysis is a method that accounts for the common variance among a set of items by their linear relations to latent dimensions or factors. It is causal, whereby the latent dimensions are assumed to cause the responses on the individual indices (van der Eijk and Rose 2015). Thus, factor analysis reduced the dimensionality of the five indices, as barometers of the strength and importance of different identities, to distil from them factors that could then be treated as ideations of identity.

Multivariate regressions were conducted to examine the correlations between these ideations of identity as independent variables and the identity index of being a Hongkonger. Additionally, to triangulate the effect of these ideations with greater nuance, multivariate regressions were conducted using each of the five identity indices described in the table. Demographic variables were then controlled for, including age, education, and place of birth.[2] Younger individuals are more likely to be associated with postmaterialist values that run against rule under the Chinese Communist Party and reject identifications as Chinese (Fong 2020). Ages were categorised into four groups: 18-29 years, 30-49 years, 50-69 years, and over 70 years. Respondents’ educational levels were controlled for, given that higher education is also related to stronger identification with postmaterialist values (Zhang, Brym, and Andersen 2017). Place of birth was also controlled for, as the geographical location of where an individual is born has a strong influence on the nature (civic, ethnic, racial, etc.) of their self-identification (Lapresta-Ray, Huguet-Canalís, and Janés-Carulla 2018).

The professional and economic backgrounds of respondents were also controlled for, namely, their occupational role and family class. Class was based on monthly family income grouped into three categories: general lower class (below HKD 9,500 per month), general middle class (between HKD 9,500 and HKD 55,000 per month), and general upper class (over HKD 55,000 per month).

Multicollinearity diagnostics were conducted on each set of variables in the statistical models to ensure that they were not multicollinear, using variance inflation factor (VIF) scores. Tests confirmed that variables were not multicollinear, with VIF scores below 5. Standard goodness-of-fit tests, and adjusted R2 and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), [3] were also conducted to compare the variance explained between model specifications.

Interview data and analysis

To supplement the quantitative results with an investigation of the meaning-making that informs ethnonational identification, this article draws on a larger project consisting of two waves of semi-structured interviews with Hong Kong youth in 2017/2018 and 2019/2020. Youth comprise a demographic category that represents symbolic contestation – and change – over ethnonational identification, especially in the Hong Kong context, where they are most commonly associated with antiestablishment sentiments (Maghbouleh 2017).

Forty-three participants, born and raised in Hong Kong, were recruited from local universities with an age range of 18 to 29. Both waves were sampled with a nonrandom sampling scheme to capture the gender proportions of youth and university students in Hong Kong.[4] Interview questions were guided by themes about how they conceived of their identities in-person and on social media, the ways their interactions with others transpired and were structured online versus in-person, and contrasts between online and offline behaviour. No differences in findings were identified across gender or the online-offline threshold, and findings converged across both waves. Data analysis was carried out through cross-comparative analysis (Attride-Stirling 2001). Preliminary themes were labelled, with the most salient used to recursively code the data again to ensure data saturation – and make sense of the different ways participants developed ethnonational identifications and the ideas behind them.

Statistical results: Chinese race and Hongkonger ethnonationalism

The results of the factor analysis are presented in Table 2. Two factors with eigenvalues above 1 were extracted using factor analysis. Factor 1 explained 42.416% variance and Factor 2 explained 26.327% variance.[5] Factors 1 and 2, and the clear demarcation between them, reveal two separate ideations that distinctly order how respondents cognise the strength and importance of their identities as measured in the indices.

Table 2. Results of factor analysis on five identity indices using varimax rotation

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| Identity index of being a Chinese citizen | 0.865 | - 0.002 |

| Identity index of being a citizen of the PRC | 0.814 | 0.054 |

| Identity index of being a member of the Chinese race | 0.789 | 0.324 |

| Identity index of being an Asian | 0.286 | 0.705 |

| Identity index of being a global citizen | - 0.064 | 0.843 |

Source: author.

The correlations of the identity indices of being a Chinese citizen, a citizen of the PRC, and a member of the Chinese race with Factor 1 can be interpreted as an ideation of Chinese identity. Simultaneously, the correlations of the identity indices of being an Asian and a global citizen can be interpreted as an ideation of cosmopolitan identity, a cognisance of belonging that surpasses Chinese and Hong Kong society.

To understand how ethnic identification is related to the strength of identification as a Hongkonger, a series of ordinary least squares regression models were conducted to explore how ideations of Chinese identity and of cosmopolitan identity are related to participants’ identity index scores of being a Hongkonger. The results are reported in Table 3.

Table 3. Results of ordinary least squares regressions of the ideations of identity against identity index of being a Hongkonger

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| Ideations of identity | ||||

| Ideation of Chinese identity | - 0.134 | 0.470* | ||

| Ideation of cosmopolitan identity | 0.316* | 0.170 | ||

| Education (ref: primary or below) | ||||

| Secondary | - 0.610 | |||

| Tertiary or above | - 0.242 | |||

| Occupation (ref: other) | ||||

| Administrative and professional worker | 0.676** | |||

| Civil and service staff | 0.978*** | |||

| Labourer | - 0.302 | |||

| Student | 0.420* | |||

| Homemaker | 0.321 | |||

| Place of birth (ref: other) | ||||

| Hong Kong | 0.690** | |||

| Mainland China | 0.387 | |||

| Class (ref: lower class) | ||||

| Middle class | 0.090 | |||

| Upper class | -0.616** | |||

| Age (ref: 18-29 years) | ||||

| 30-49 years | -0.178 | |||

| 50-69 years | 0.076 | |||

| 70 years or above | 0.010 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.047 | 0.355 | ||

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 13.08 | 9.34 | ||

Note: *p < 1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Source: author.

From Table 3, it is observed that in Model 1, only ideations of Chinese identity and of cosmopolitan identity were included. The findings show that only ideation of cosmopolitan identity is positively and significantly correlated with the identity index of being a Hongkonger. However, once education, occupation, place of birth, class, and age are controlled for in the full model (Model 2), the results surprisingly show that ideation of Chinese identity is significantly related to a higher identity index score of being a Hongkonger. Age and education level are not related to identifying as a Hongkonger. In terms of class, being general upper class is significantly related with lesser identification as a Hongkonger. Unsurprisingly, Hong Kong as place of birth is significantly related to identifying as a Hongkonger. In terms of occupations, administrative and professional workers, civil and service staff, and students are significantly related to identifying as a Hongkonger.

Model fit tests give credence to the explanatory power of the full model. Adjusted R2 showed that whereas the factors alone only explained 4.7% of variance, the full model explained 35.5% of variance in the identity index of being a Hongkonger. The RMSE results were consistent with this improvement, showing a marked decrease in the full model that indicates improved model fit.

Ordinary least squares regressions on the identity index of being a Hongkonger were conducted using the individual identity indices. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Results of ordinary least squares regression of identity indices on identity index of being a Hongkonger

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| Identity index | ||||

| Identity index of being a Chinese citizen | - 0.037 | 0.285 | ||

| Identity index of being a citizen of the PRC | - 0.202 | - 0.433 | ||

| Identity index of being a member of the Chinese race | 0.057 | 0.881** | ||

| Identity index of being an Asian | 0.138 | - 0.169 | ||

| Identity index of being a global citizen | 0.214 | 0.155 | ||

| Education (ref: primary or below) | ||||

| Secondary | - 0.433 | |||

| Tertiary or above | - 0.047 | |||

| Occupation (ref: other) | ||||

| Administrative and professional worker | 0.748** | |||

| Civil and service staff | 1.184*** | |||

| Labourer | - 0.223 | |||

| Student | 0.759*** | |||

| Homemaker | 0.333 | |||

| Place of birth (ref: other) | ||||

| Hong Kong | 0.647** | |||

| Mainland China | 0.270 | |||

| Class (ref: general lower class) | ||||

| General middle class | 0.037 | |||

| General upper class | - 0.970*** | |||

| Age (ref: 18-29 years) | ||||

| 30-49 years | - 0.109 | |||

| 50-69 years | 0.405 | |||

| 70 years or above | 0.332 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | - 0.038 | 0.631 | ||

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 12.23 | 6.24 | ||

Note: *p < 1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Source: author.

Model 1 shows no significant correlations. Model 2 shows new predictors of identification as a Hongkonger. The results in Table 4 corroborate those in Table 3 in terms of occupations, place of birth, class, and age. Age is nonsignificant. Being upper class significantly predicts lower odds of identifying as a Hongkonger. Meanwhile, membership in administrative and professional, civil and service, and student occupations significantly predict higher odds of identifying as a Hongkonger. However, Model 2 also shows that, by way of identity indices, identifying as a member of the Chinese race has a significantly positive effect on the odds of identifying as a Hongkonger.

Corresponding with the non-significance in Model 1, the adjusted R2 for it was negative (indicating no explanatory power). The full model (Model 2) showed however a significant improvement by explaining 63.1% of the variance with identification as a Hongkonger (corroborated by a markedly lower RMSE score).

Qualitative findings: Ideating ethnonational hinges

The perplexing interrelationships between the two separate identities are elaborated upon by interviewees as refractions of everyday realities. Participants drew attention to dual pressures to conform from everyday interactions with the nonfamilial and familial segments of their social networks that prompted them, in response, to develop two separate identities that they performed for each (a civic Hongkonger identity and a pan-Chinese racial identity).

According to Jason, a 26-year-old manager at a local business:

I just keep a low-profile. But a lot of my friends (…) are very concerned about the city. I just have a look at their stuff on social media… If I made a post, I might feel like I was part of a big group, like we were all in solidarity. But I also have to be a part of another group (…) I am concerned too (…) about the reaction of my family (…), my parents actually. I think that if I just make one comment on a post, it will most likely cause a discussion that lasts the whole night. So, maybe I just agree with my friends in private messages, and hide them from my family. In front of my family, I switch to a different, nonpolitical person. (Interview, July 2017)

Jason sought to expunge overt discussions of politics on social media on account of his family, especially his parents, whose views he did not wish to appear at odds with. In his account, the risk felt considerable, given the upspring of political opinions voiced from his nonfamilial ties who were sympathetic to the ongoing unrest and expected him to follow suit. Mediating these competing pressures for conformity, Jason reported switching between the two identities, flexibly migrating between two sets of performances that he kept in isolation from one another, namely, private messaging about politics with his peers while discussing nonpolitical issues with his family.

For Esther, a 23-year-old law student, the ubiquity of imagery from the movement on Instagram and Facebook made it an inescapable topic of discussion among her friends and a source of pressure to constantly signal her support. Even after her concern for the movement had diminished, the pressure she felt to conform with her peers loomed large in her derivations of a (civic) identity. In her own words:

Some of my friends posted something like “I will never be afraid” on the public biography section at the front of their Instagram profiles. This was a bit extreme to me. It made me feel a bit suffocated (…), like I also had to keep waving the flag for it by resharing news and stories on my own personal stories. (Interview, August 2019)

When her friends’ preoccupation with the movement had outlasted her own initial interest, she continued to signal loyalty and to cultivate her sense of belonging with the group by sharing individual posts and news articles on the ongoing unrest. This was especially the case among law student and lawyer circles, especially solicitors, who assumed active roles in demonstrations during the unrest (Liu, Hsu, and Halliday 2019). However, Esther carefully traced the motivation for such performances to pressures for conformity in her peer reference groups. When prompted to position her family within this narrative, Esther referenced separate identities:

- I feel like I do have two identities. One outside the house (…). One inside the home, when I’m with family. - Interviewer: Where does national belonging fit into that? - Well, I think that I belong to a unique Hong Kong society [but] I also want to belong with my friends and my family. But they require different things (…). My family doesn’t agree with the movement, perhaps because they’re older. But I think my identity is different in the family. Outside the home, we can negotiate our nationality because that is just politics and government, but race is something more… essential. More genetic. It’s what my parents and grandparents and ancestors are. We are all the same race. (Interview, August 2019)

Friends and family occupied two dislocated parts of social networks, in Esther’s account, and whose boundaries were closed. Yet, the same upkeep demands for conformity and reciprocity held true across both domains. In response to these competing tensions, Esther loosened the social psychological boundaries between race and ethnicity to preserve her sense of belonging in both spheres. Political unrest in 2019 prompted her to continually demand her to perform or demonstrate her belief in a unique Hongkonger civic identity within her friendship ties. Salient in her account, however, was the politicisation of this identity and its demarcation from her racial identity, which she saw to be an essentialist and genetic characteristic that her family (and her sense of belonging in her family) was structured by.

Additionally, the two identities were not merely balanced, but switched across in participant accounts. As Chen, a 20-year-old student, remarked:

When I say I am a “Hongkonger,” I think of national identity, which is something political, yes. It has to do with getting to decide laws and policies. But that doesn’t mean I’m an entirely different species than Mainland Chinese. My family does identify as Chinese, and I see that I am part of them too. I also don’t want to cut off ties with my family by creating a big scene at home over political issues. I think the family is where we are all together, when we can put politics to the side. So, I embody one identity on Instagram with friends and another when I’m with [my family]. (Interview, July 2017)

Evident in his account is the practice of switching across the ethnonational hinge, between a civic identity that demarcates Hongkongers from Mainland China on the basis of politics and a Chinese racial identity that transcends this divide. Moreover, the switch itself was not merely to cultivate favourable evaluations among in-group members, but to preserve a sense of personal security in individuals such as Chen himself. That is, maintaining personal reputation in his social networks was important, but so was ideating the existence of an ethnonational hinge itself. On a meta-level, this hinge helped him cope with the perceived tensions between the separate parts of his social networks whose political views clashed, offering him the assurance that he had a coping mechanism to preserve his reputation among the two groups and prevent himself from being torn apart. In similar fashion, Katy, a 29-year-old business consultant, remarked:

- I think some [locals] were uneasy about integrating with Mainland China. The flare-up was part of that (…). I just stepped outside in Central. Tonnes of colleagues talk a lot about it. I might agree with the sentiment of the event, but I won’t want it to be my whole identity. I live with my parents, my husband, and my two-year-old daughter, and I don’t want to talk about it in front of them.

- Is being of Chinese race an important part of that conversation with your family?

- It’s the only thing [that connects us all]! Maybe when my daughter is older, we can have a conversation about identity. I want her to be informed, but I don’t want her to grow up thinking she lives in a divisive city, where A is different from B, and they have to hate each other. I don’t want her to be involved in adults’ [political] battles. (Interview, July 2019)

Like Esther and Chen, peer groups in nonfamilial spaces such as work prompted Katy to politicise her construction of (ethnonational) identity in light of the ongoing unrest. Family was the fulcrum that pivoted her identity-making to the other end of the ethnonational hinge, leading her to stress commonality through a pan-Chinese race as the most essentialist and obvious phenotypical link through her entire family.

This switch across the ethnonational hinge demonstrates, for participants such as Chen and Katy, a desire to uphold rather than disrupt the status quo of their social relations. In this manner, ethnonational hinge-switching reflects a conceptualisation of identity as a grounded response to the immediacy of their environments, one that can shift their identity (both in self-perceptions and to their peers) fluidly between a Hongkonger civic identity and a pan-Chinese racial identity. This finds resonance with cognitive cultural theory: it demonstrates that while political identities among friendship ties draw from deliberate and rule-based reasoning (rendering ethnicity a ground on which to draw national lines), identities rooted in families draw upon declarative stores of culture that are activated automatically (invoking race in identity-making as a form of autobiographical, habitual thinking).

Discussion

Adopting a relational approach to the ethnonational classification of the Hongkonger identity, this article contributes to the literature from which it draws by casting new light on nuances in the interrelationships between variegated occupational statuses and demographic attributes in their effects on identifying as a Hongkonger.

This article finds that while being a student is positively correlated with identifying as a Hongkonger, age groups surprisingly do not (as Figure 1 might otherwise lead us to believe) and neither does level of education (as the postmaterialist argument might otherwise suggest). Furthermore, students were not the only occupation that predicted identification as a Hongkonger, as commonly described by mainstream media and academic scholarship: administrative and professional workers, and civil and service staff also did. A latent class dimension was observed in identification as a Hongkonger, namely, that individuals belonging to higher classes were less likely to do so. This article also finds that identification as part of the Chinese race is associated with identification as a Hongkonger.

According to interviews with young Hong Kong locals, the demographic category where political dissatisfaction is most prevalent, this association between identification as part of the Chinese race and identification as a Hongkonger was ideated as two ends of an ethnonational hinge. Individuals made use of this ethnonational hinge to “open or close the door” to dislocated parts of their social networks as necessary (Maghbouleh 2017: 5). Put differently, identification with “common Chinese race” recognises the influence of family and race from which individuals draw symbols, rituals, and worldviews to inform another side of their ethnonational identification (Swidler 2001: 202). Torn between competing demands for conformity between peer groups and family, as in the cases of Jason, Esther, Chen, and Katy, was responded to by conceptualising identity as a dual civic Hongkonger identity and pan-Chinese racial identity across which individuals could switch depending on their interlocutors (whether they were nonfamilial or familial ties).

Ultimately, the porousness of boundaries between Chinese racial identification and Hongkonger ethnonational identification is a useful heuristic for the contradictory nature of ethnonational meaning-making that moves beyond conceptualisations of a binary and beyond the explanatory power of one-dimensional typecasting under values such as anti-Sinoism (Swidler 2001: 86-7). Ethnonational identification as a cultural process is not neat, orderly, or based on individual proclivities, but is relational in nature. In the case of the Hongkonger identity, it emerges that meaning-making is fluid, naturally unstable, and draws from multiple sources that move beyond fixed occupational roles or age groups (such as to include the family) to bring countervailing and contradictory meanings of what it means to be a Hongkonger into the process of ethnonational identification.

Given that participants appear to change their answer depending on their context, it may be inferred that their research participation is no different. However, methodological tests of survey responses and subsequent behaviour, for instance, find that what people say they will do generally coincides with what they do (e.g., how they vote, Hainmueller, Hangartner, and Yamamoto 2015). It also emerges that individuals tend to “switch” across their ethnonational hinges based on interactions with reference groups, or groups of individuals they closely interact with repeatedly and from whom they ultimately learn norms and practices (as opposed to one-time research participation).

A line of future research this article lends support to is ethnonational identification as a latent source of inequality in Hong Kong. As Lamont, Beljean, and Clair (2014) theorise, inequality is not just about the distribution of material resources, but also of symbolic resources that involve status signals and networked segregation on the basis of these signals. The association of a “common Chinese race” with a Hongkonger identity could portend important variations in the enactment of inequality based on hitherto neglected criteria, such as if individuals identifying with the Hongkonger ethnonational identity exclude other residents based on their country of birth.

Manuscript received on 16 December 2022. Accepted on 24 August 2023.

References

ABRUTYN, Seth, and Omar LIZARDO. 2023. “A Motivational Theory of Roles, Rewards, and Institutions.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 53(2): 200-20. ABU-LABAN, Yasmeen, and Abigail BAKAN. 2008. “The Racial Contract: Israel/Palestine and Canada.” Social Identities 14(5): 637-60. ATTRIDE-STIRLING, Jennifer. 2001. “Thematic Networks: An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 1(3): 385-405. AU, Anson. 2022. “Guanxi in an Age of Digitalization: Toward Assortation and Value Homophily in New Tie-formation.” The Journal of Chinese Sociology 9(1): 1-19. ——. 2023. “Framing the Purchase of Human Goods: The Case of Cosmetic Surgery Consumption in Capitalist South Korea.” Symbolic Interaction 46(1): 72-93. BARBALET, Jack. 2021. The Theory of Guanxi and Chinese Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. BIAN, Yanjie, and Ken’ichi IKEDA. 2018. “East Asian Social Networks.” In Reda ALHAJJ, and Jon ROKNE (eds.), Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining (2nd ed.). Cham: Springer. 679-701. BOURDIEU, Pierre. 1979. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. CALHOUN, Craig. 1994. Social Theory and the Politics of Identity. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. CERULO, Karen. 2010. “Mining the Intersections of Cognitive Sociology and Neuroscience.” Poetics 38(2): 115-32. CHAI, Sun-ki. 2005. “Predicting Ethnic Boundaries.” European Sociological Review 21(4): 375-91. CHAN, Chi Kit, and Anthony FUNG. 2018. “Disarticulation between Civic Values and Nationalism: Mapping Chinese State Nationalism in Post-handover Hong Kong.” China Perspectives 114: 41-50. CHEW, Matthew. 2022. “How the ‘Commercialized Performance of Affiliative Race and Ethnicity’ Disrupts Ethnoracial Hierarchy: Boundary Processes of Customers’ Encounter with South Asian Waitpersons in Hong Kong’s Restaurants.” Sociology 56(2): 333-50. CHIU, Chi-Yue, and Letty Yan-Yee KWAN. 2016. “Globalization and psychology.” Current Opinion in Psychology 8: 44-8. CHOW, Siu-lun, King-wa FU, and Yu-Leung NG. 2020. “Development of the Hong Kong Identity Scale: Differentiation Between Hong Kong ‘Locals’ and Mainland Chinese in Cultural and Civic Domains.” Journal of Contemporary China 29(124): 568-84. CHUI, Wing Hong, Paul KHIATANI, and Ping Lam IP. 2022. “Emerging Adults’ Intentions to Participate in Radical Protest Actions: The Role of the Parents in the Midst of Extra-familial Influences and the Offspring’s Political Characteristics.” British Journal of Social Work 52(7): 4057-76. CHUNG, Hiu-Fung. 2020. “Changing Repertoires of Contention in Hong Kong: A Case Study on the Anti-extradition Bill Movement.” China Perspectives 122: 57-63. DICKENS, Danielle, Veronica WOMACK, and Treshae DIMES. 2019. “Managing Hypervisibility: An Exploration of Theory and Research on Identity Shifting Strategies in the Workplace among Black Women.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 113: 153-63. DiMAGGIO, Paul. 1997. “Culture and Cognition.” Annual Review of Sociology 23: 263-87. FONG, Brian. 2020. “Stateless Nation within a Nationless State: The Political Past, Present, and Future of Hongkongers, 1949-2019.” Nations and Nationalism 26(4): 1069-86. FUNG, Anthony. 2004. “Postcolonial Hong Kong Identity: Hybridising the Local and the National.” Social Identities 10(3): 399-414. GOLDSTEIN, Joshua, and Guy STECKLOV. 2016. “From Patrick to John F.: Ethnic Names and Occupational Success in the Last Era of Mass Migration.” American Sociological Review 81(1): 85-106. HAINMUELLER, Jain, Dominik HANGARTNER, and Teppei YAMAMOTO. 2015. “Validating Vignette and Conjoint Survey Experiments against Real-world Behavior.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112(8): 2395-400. HO, Justin. 2022. “Understanding Hong Kong Nationalism: A Topic Network Approach.” Nations and Nationalism 28(4): 1249-66. IP, Iam-chong. 2015. “Politics of Belonging: A Study of the Campaign Against Mainland Visitors in Hong Kong.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 16(3): 410-21. ——. 2020. Hong Kong’s New Identity Politics: Longing for the Local in the Shadow of China. London: Routledge. KAUFMAN, Jason. 2004. “Endogenous Explanation in the Sociology of Culture.” Annual Review of Sociology 30: 355-87. KILEY, Kevin, and Stephen VAISEY. 2020. “Measuring Stability and Change in Personal Culture Using Panel Data.” American Sociological Review 85(3): 477-506. KU, Agnes S. 2020. “New Forms of Youth Activism: Hong Kong’s Anti-extradition Bill Movement in the Local-national-global Nexus.” Space and Polity 24(1): 111-7. LAMONT, Michèle. 2000. The Dignity of Working Men: Morality and the Boundaries of Race, Class, and Immigration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ——. 2014. “Reflections Inspired by Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks by Andreas Wimmer.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37(5): 814-9. LAMONT, Michèle, Stefan BELJEAN, and Matthew CLAIR. 2014. “What is Missing? Cultural Processes and Causal Pathways to Inequality.” Socio-Economic Review 12(3): 573-608. LAMONT, Michèle, and Virág MOLNÁR. 2002. “The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences.” Annual Review of Sociology 28: 167-95. LAMONT, Michèle, and Laurent THÉVENOT. 2000. Rethinking Comparative Cultural Sociology: Repertoires of Evaluation in France and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. LAPRESTA-REY, Cecilio, Ángel HUGUET-CANALÍS, and Judit JANÉS-CARULLA. 2018. “Opening Perspectives from an Integrated Analysis: Language Attitudes, Place of Birth and Self-identification.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21(2): 151-63. LEE, Francis. 2020. “Solidarity in the Anti-extradition Bill Movement in Hong Kong.” Critical Asian Studies 52(1): 18-32. LEE, Francis, and Chi Kit CHAN. 2022. “Political Events and Cultural Othering: Impact of Protests and Elections on Identities in Post-handover Hong Kong, 1997-2021.” Journal of Contemporary China. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2022.2159756 LEE, Siu-yau. 2020. “Explaining Chinese Identification in Hong Kong: The Role of Beliefs about Group Malleability.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 43(2): 371-89. LIU, Sida, Ching-Fang HSU, and Terence C. HALLIDAY. 2019. “Law as a Sword, Law as a Shield: Politically Liberal Lawyers and the Rule of Law in China.” China Perspectives 116: 65-73. LIZARDO, Omar. 2021. “Culture, Cognition, and Internalization.” Sociological Forum 36: 1177-206. LIZARDO, Omar, and Michael STRAND. 2010. “Skills, Toolkits, Contexts and Institutions: Clarifying the Relationship between Different Approaches to Cognition in Cultural Sociology.” Poetics 38(2): 205-28. MA, Eric. 1999. Culture, Politics, and Television in Hong Kong. London: Routledge. MA, Eric, and Anthony FUNG. 1999. “Re-sinicization, Nationalism and the Hong Kong Identity.” In Clement SO, and Joseph CHAN (eds.), Press and Politics in Hong Kong: Case Studies from 1967 to 1997. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. 497-528. ——. 2007. “Negotiating Local and National Identifications: Hong Kong Identity Surveys 1996-2006.” Asian Journal of Communication 17(2): 172-85. MA, Ngok. 2011. “Values Change and Legitimacy Crisis in Post-industrial Hong Kong.” Asian Survey 51(4): 683-712. MAGHBOULEH, Neda. 2017. The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race. Stanford: Stanford University Press. MATHEWS, Gordon, Eric MA, and Tai-Lok LUI. 2008. Hong Kong, China: Learning to Belong to a Nation. London: Routledge. MILES, Andrew, and Stephen VAISEY. 2015. “Morality and Politics: Comparing Alternate Theories.” Social Science Research 53: 252-69. NG, Sik Hung, and Julian C. L. LAI. 2011. “Bicultural Self, Multiple Social Identities, and Dual Patriotisms among Ethnic Chinese in Hong Kong.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42(1): 89-103. O’ROURKE, Diane, and Johnny BLAIR. 1983. “Improving Random Respondent Selection in Telephone Surveys.” Journal of Marketing Research 20(4): 428-32. SANDERS, Jimy M. 2002. “Ethnic Boundaries and Identity in Plural Societies.” Annual Review of Sociology 28: 327-57. SHEK, Daniel. 2020. “Protests in Hong Kong (2019-2020): A Perspective Based on Quality of Life and Well-being.” Applied Research in Quality of Life 15(3): 619-35. STEINHARDT, H. Christoph, Linda Chelan LI, and Yihong JIANG. 2018. “The Identity Shift in Hong Kong since 1997: Measurement and Explanation.” Journal of Contemporary China 27(110): 261-76. SWIDLER, Ann. 2001. Talk of Love: How Culture Matters. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. van der EIJK, Cees, and Jonathan ROSE. 2015. “Risky Business: Factor Analysis of Survey Data-assessing the Probability of Incorrect Dimensionalisation.” PLoS ONE 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118900 VEG, Sebastian. 2016. “Creating a Textual Public Space: Slogans and Texts from Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement.” Journal of Asian Studies 75(3): 673-702. ——. 2017. “The Rise of ‘Localism’ and Civic Identity in Post-handover Hong Kong: Questioning the Chinese Nation-state.” The China Quarterly 230: 323-47. WALLACE, Derron. 2017. “Reading ‘Race’ in Bourdieu? Examining Black Cultural Capital among Black Caribbean Youth in South London.” Sociology 51(5): 907-23. WIMMER, Andreas. 2008. “The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 113(4): 970-1022. ——. 2013. Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. WONG, Mathew, Paul KHIATANI, and Wing-hong CHUI. 2019. “Understanding Youth Activism and Radicalism: Chinese Values and Socialization.” The Social Science Journal 56(2): 255-67. WUTHNOW, Robert. 2018. The Left Behind: Decline and Rage in Rural America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ZHANG, Tony, Robert BRYM, and Robert ANDERSEN. 2017. “Liberalism and Postmaterialism in China: The Role of Social Class and Inequality.” Chinese Sociological Review 49(1): 65-87.[1] Hong Kong PORI (Public Opinion Research Institute), “Categorical Ethnic Identity,” www.pori.hk/pop-poll/ethnic-identity-en/q001.html?lang=en (accessed on 14 March 2024).

[2] Gender is not included because it is not theoretically linked to the nature of one’s identification in Hong Kong/China, nor empirically demonstrable to have any effect on this identification (Lee S. Y. 2020). Its exclusion also reduced the variance that the models accounted for.

[3] Unlike the adjusted R2 that measures proportion of variance explained, RMSE is used as a relative measure to compare model fit across model specifications, where a lower value suggests better fit.

[4] The University of Hong Kong, 2016, “A Profile of New Full-time Undergraduate Students,” www.cedars.hku.hk/publication/UGprofile/UG1516FullReport.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2024).

[5] Rotated using varimax with Kaiser normalisation (rotation converged in three iterations).