BOOK REVIEWS

Precarious Employment, Pension Participation, and Retirement Deferment in China

Xueyang Ma is a postdoctoral researcher at the School of Political Science and Public Administration, Wuhan University, 299 Bayi Road, Wuhan, 430072, China (xueyangma@yeah.net).

Zengwen Wang (corresponding author) is Professor at the School of Political Science and Public Administration and Deputy Director of the Research Centre of Social Security, Wuhan University, 299 Bayi Road, Wuhan, 430072, China (wzwlm922@163.com).

Jie Zhang is an assistant lecturer at the School of Humanities and Management, Southwest Medical University, 1 Xianglin Road, Luzhou, 646000, China (jiezhang518@126.com).

Jian Wu is Lecturer at the School of Health Policy and Management, Nanjing Medical University, 101 Longmian Avenue, Nanjing, 211166, China (wujian0304@njmu.edu.cn).

Introduction

In China, the statutory retirement ages of 60 for male workers and 50 for female workers have been in place since the Labour Insurance Regulations was introduced in 1951. At that time, the average life expectancy was below 45 years old (Jing et al. 2021) but has now reached 78 years old.[1] With an ageing society and slow population growth, some policymakers and scholars advocated raising the statutory retirement ages (RSRA) to cover the pension deficit and increase the workforce. The proposed new statutory retirement ages vary – for example, 55 for all women first, and then 60 or 65 for both genders. These proposals have received strong opposition from workers, especially those with precarious employment.

China’s precarious employment has expanded with the socioeconomic transformation after the 1970s, which has changed plentiful full-time employment into non-standard, part-time, casual or informal ones. Many commentors have noted that China’s important growth, poverty alleviation, and livelihood improvement, and the increased access to social insurances in the twenty-first century, resulted in part from this restructured employment (Tang 2002; Huang, Zhang, and Xue 2018). Negative outcomes may be observed not only among workers but also in the social welfare system. For instance, the establishment of an urban workers’ social pension system was primarily designed to cover employees in work units (danwei 單位), including state-own enterprises (SOEs) and cooperatives, and also commercial organisations, through well-regulated laws and the standardised and effective collection of funds from employees (Sun and Suo 2007). Even after it was reformed to theoretically include all types of employees (Yuan 2022: 19), the pension system has remained employment- and earning-related (Zhu and Walker 2018). As a result, when precarious and informal workers, who are rarely involved in work units and face the risks of underemployment as well as inadequate and interrupted income, became the mainstream of China’s workforce (Huang 2009), the pension system faced serious challenges as to its effectiveness, participation rates and duration, and other socioeconomic expectations.

The research developed in this article aims to explain precarious workers’ pension participation and attitudes towards RSRA through a sociological framework on China’s precarious employment. Unlike most conventional studies on China’s post-reform labour market such as those from informal and flexible employment perspectives, this framework focuses not only on the uncertainty of precarious employment (Chan 2013) but also on its consequences in and beyond employment. Drawing on literature on precarious employment and on China’s labour market reforms, this study finds that uncertainty in employment is characterised by instability, individualisation (in this article, individuals detaching from the collective or having no formal affiliation with any work units), and insecurity. Focusing on pensions including retirement policies, the field research reveals three understudied consequences in terms of (a) experience and cognition, (b) institutionalised inequality, and (c) the extension of precarity and inequality from employment into retirement. The framework contributes to analysing the complex mechanism behind the process in which the interplay between the labour market and public policies influences workers’ pension and retirement strategies and the outcomes of policies. This in turn contributes to clarifying the lasting effects of increasing precarity on China’s changed labour market institutions.

Through in-depth interviews with 68 individuals experiencing precarious employment, the article argues that precarious employment inhibits participation in the Urban Employee Basic Pension (UEBP, chengzhen zhigong jiben yanglao baoxian 城鎮職工基本養老保險),[2] and that the impact of this decreased participation is compounded if working life is extended. Individualisation, instability, and insecurity in employment boosts institutionalised inequality in the UEBP. Especially in a working environment that lacks coworkers who can promote understanding of the UEBP system, the pressure and anxiety resulting from an unpredictable livelihood, coupled with the lack of a compulsory contribution obligation, increasing UEBP premiums, and distinct contribution rate gaps among those with and without a work unit, discourages the participation of precarious workers in the UEBP. In theory, RSRA could enhance the accumulation of pension contributions by precarious workers; however, given these workers’ strategy to minimise their contributions, RSRA is likely to restrict their retirement arrangements, thus leading to more uncertainty, insecurity, and anxiety for them.

Precarious employment and basic pension structures for workers in China

In research on new institutionalism and its choice-within-constraints framework, Ingram and Clay (2000), as well as Petracca and Gallagher (2020), argue that an institution (the collectively shared and relatively permanent regulations, norms, rules and so forth) or institutional system coexists with other interconnected systems, social practices, and social interactions, which enables and constitutes people’s cognitive processes (and behaviour), in turn affecting the outcomes of the institution. Our study focuses on the interaction between the “rules of the game” in the labour market, and pension and retirement policies, and how their interaction works on workers’ pension and retirement decisions. These lenses further enable the present research to analyse and anticipate the policy outcomes of RSRA. Combining the literature reviewed below, the theoretical argument and explanation were constructed as follows: the UEBP formed on the basis of full employment and mainly protecting formal workers is mismatched with a labour market that has been reconstructed towards increasing precariousness and serves to amplify the precarity and inequality that precarious workers face. This incompatibility, in turn, reshapes precarious workers’ perception of and attitudes towards the UEBP, resulting in their decision to limit UEBP participation and resist RSRA.

Precarious employment in China: Instability, individualisation, and insecurity

Precarious employment, in contrast to the Fordist-Keynesian employment model, refers to unpredictability in having a paid job (for the employed) or profit-seeking activities (for the self-employed) (Kalleberg 2009). The term “precarious employment” can be synonymous with the more commonly employed Chinese terms of “informal employment (feizhengshi jiuye 非正式就業)” (emphasising economic and production sectors not well regulated by laws)[3] or “flexible employment (linghuo jiuye 靈活就業)” (underscoring how the organisation adapts the workforce to a changing environment through non-standard work arrangements; see Dettmers, Kaiser, and Fietze 2013). Relatively speaking, the term “precarious employment” highlights uncertainty and its results.

Employment (un)certainty denotes employment (dis)continuity (Allen and Henry 1997) and is also linked to contractualisation (Standing 2008). In China’s employment context, this is expressed in employment instability and individualisation, respectively. Market-oriented economic reforms undermined stable and standard employment as well as the iron rice bowl (a system of guaranteed lifetime employment). This entailed: large-scale layoffs of workers, especially in SOEs; a massive influx of rural migrant workers into cities; the encouragement of self-employment and mass microenterprises; and the legalisation of subcontracting, labour service relations,[4] and internships (Lee and Kofman 2012; Lee 2019). More recently, the digital economy (Sun and Chen 2021), culture and creative industries (Pun, Chen, and Jin 2024), and education industries (Si 2024) have become new containers of precarious workers. Hence, as in the West (Kalleberg 2009), somewhat challenging the dual labour market theory that sees inequality in the secondary labour market, precariousness may also be observed in the primary labour market, and not all precarious workers are in low-tier value chains or have low pay.

Why are precarious workers considered “vulnerable”? In addition to short-term employment periods that make livelihood unsustainable and life schedules irregular, the individual and uncontracted workers are usually excluded from formal protection, resulting in multiple forms of insecurity for them. For example, in the conceptualisation of precarious jobs, Kalleberg (2009) and Standing (2011: 10-3) identify multiple insecurities ranging from economic interests to emotional, bodily, family, social status, and political representation. As such, there are lasting consequences for people employed as “precarious workers” (Campbell and Price 2016).

Focusing on precarious workers’ pension participation and retirement strategies in China, the field research in this study underlined three key yet underexplored aspects of these lasting consequences: experiences and cognition; institutionalised inequality; and the extension of precarity and inequality from employment into retirement.

(a) Experience and cognition

Precarious employment shapes emotions and information sources in workers’ cognition and behavioural processes. While recent research stresses autonomy in precarious workers’ decision-making, employment precarity is often viewed as a chronic family stressor (Goldberg and Solheim 2021), especially in the absence of appropriate protection from the wider society. Given that literature suggests that the experiences of precarious employment harm workers’ mental health (Irvine and Rose 2024), it can be believed that the instability and insecurity of precarious employment creates concerns about unpredictable livelihood and life that may be amplified by uncertainty situated in other relevant institutions. For example, Collard (2013) notes that policy changes bring distrust towards the institution. Like the cognitive function played by institutions in shaping people’s rationality, emotion also contains an epistemic function and works on agency (Tappolet 2016: 118). Precarious employment and its interconnected institutions (here, pension and retirement policies) therefore inevitably have an impact on workers’ living arrangements, including pension participation and retirement strategies.

As to the sources of information, exchange, and learning likewise entailed by individualisation, learning theory and peer effects demonstrate the importance of observing and imitating others in forming one’s own cognition and behaviour (Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer, and Welch 1992; Ng and Wu 2010). An empirical study in the United Kingdom suggests that colleagues’ encouragement and participation in pension schemes can increase employees’ contribution rates and levels (Robertson-Rose 2019). Research about China’s rural pension scheme also illustrates peers’ influence on pension participation decisions and levels (Zhao and Qu 2021). As such, the lack of references and information sharing among individual workers with few long-term, stable, and sustainable interpersonal relationships in the workplace owing to mobility and dispersion (Sun and Chen 2021; Peng 2022) means that such workers have difficulty accruing sufficient information and motivation to participate in pension schemes that are geared towards full-time employment and industrial production.

Workers’ basic pension structures and inequality for precarious workers

Another point easily overlooked is that precarity extends from employment to social dimensions. With reform and opening up, pension and old-age insurance policies have been amended and adjusted many times since the 1990s to become “universal” but still “fragmentary,” as pension participants are divided among urban employees, government and public institution staff, and urban and rural residents (Liu and Sun 2016). The UEBP, which covers urban employees regardless their urban or rural household registration (hukou 户口), further classifies its participants as either work-unit enrollers or individual enrollers.

(b) Institutionalised inequality

“Law and custom shaped men’s preferences and institutionalized power and privilege, thus converting natural inequalities into more pernicious social inequalities” (Immergut 1998: 9). Some argue that the UEBP mainly protects those who have a formal and usually stable work relationship with a work unit, but not precarious workers (Mok and Qian 2019; Chan and Hui 2023). Although each work-unit employee must register for the UEBP, the self-employed and those without stable employment are merely “encouraged” to enrol in the scheme (Wang and Huang 2023). As such, these workers enjoy more autonomy, but it excludes a great many of them from the UEBP (ibid.).

The policy provides “flexible” workers (i.e., without regular work units or periods of employment), with two channels to UEBP enrolment. One permits a microenterprise or small-scale employer, which cannot be identified as a work unit, to enrol in the UEBP as a work-unit enroller – or, more accurately, work-unit emulator – when employing more than seven workers. The other way is for workers outside of a work unit to enrol as an individual.

Depending on the employer’s identity and status, it can be legal for employers not to enrol their employees in the UEBP. There are two types of employer-employee relationships. One is a labour relationship, where the law requires the employer to be a work unit, and the employee to have an affiliated relationship. This employer has the responsibility to enrol in and contribute to social insurance as a work-unit enroller. With the work unit contributing 16% of the total taxable payroll, a work-unit worker only pays a UEBP premium of 8% of his or her own average wage from the previous year. The other is a service relationship. Without affiliation between the employer and the employee, the employer has no obligation to contribute to employees’ social insurance. Some scholars have criticised this as an institutional loophole that inhibits relevant workers from social insurance participation (Chow and Xu 2018; Jiang, Qian, and Wen 2018). By not enrolling as a work unit, or by relying on a service relationship, small-scale employers, either individuals or organisations, can “legally” deprive precarious workers of the benefits of the UEBP, or can regard contributions to the UEBP as a negotiable issue with their employees (Guo et al. 2016).

As to the second way, enrolling as an individual also applies to the self-employed. This is a loophole to the provision of a pension, but the question then arises as to precarious workers’ ability to participate in the UEBP earnings-related scheme (Liu and Sun 2016). Without employer involvement, the idea that the UEBP represents “deferred wages” (Meng 2019: 22-58) is questionable. Individual enrollers have to cover all UEBP costs themselves, choosing to contribute an amount between “the provincial average wage x 20% x 60%” and “the provincial average wage x 20% x 300%.” Even if some informal workers have much higher wage rates than most formal workers, the impermanence of their lucrative incomes (Dong 2020) would constrain their (sustainable) ability and desire to participate in the UEBP. As was found in the UK, employees’ feelings regarding the settlement of their jobs, careers, and lives influence their future planning, so fixed-term contracts and erratic employment detract from voluntary pension participation (Robertson-Rose 2019); not to mention that in a developing country with prevailing middle-low wages (Zhou 2013) and a strong family-first tradition (Guo et al. 2016), expenditure on the UEBP seems outside of a worker’s budget (Zhao 2023).

(c) The spread of precarity and inequality from employment to retirement

Precarity may continue into retirement if workers contributed at a low level to the UEBP when employed. A worker must have at least 15 years of contributions before retirement in order to be entitled to a pension. For both individual and work-unit workers as UEBP enrollers, the monthly pension a retiree receives depends on the local average wage, the years of contribution, and the level of contribution (Zhu and Walker 2018). The policy sets an ideal replacement rate of UEBP pension at 60% of the average wage (Dong and Wang 2016). However, it was only 35% in Sichuan Province in 2021.[5]

Wang and Huang (2023) propose pension equality in terms of equal access, equal structures and rules, and equal benefit allocation, in relation to which workers in precarious employment could be assessed as “unequal.” As will be shown in the empirical sections, with different premiums, access to the UEBP was unequal for work-unit and individual enrollers. Those in the most precarious situations were excluded from the most basic pension, the UEBP. Further to that, the benefit was unequal when employment income decided the amount of pension received. Zhu and Walker (2018) therefore criticised the current pension institution because it privileged the advantaged.

RSRA would expand the negative effects on the ongoing welfare of those workers. Pressure produced by employment may carry on into retirement, not only because of the difficulty of precarious workers in participating in the UEBP, but also because a person’s financial situation, work experience, and health influence his or her retirement decisions and preferences (Furunes et al. 2015). Previous research supports the observation that precarious workers’ retirement life is risky (Dong and Wang 2016; Wang and Huang 2023), so they tend to engage in bridge employment – which means retiring but not completely exiting the labour market – in order to meet financial needs and maintain self-identity that is usually gained through career and work (Niesel et al. 2022). However, if the pension coverage and replacement rates are too low, bridge employment becomes a survival strategy instead of a choice (Kim, Baek, and Lee 2018). The positive effect of receiving a pension – compensating for the economic anxiety caused by precarious employment (Ashwin, Keenan, and Kozina 2021) – might be mediated by RSRA.

Data collection and analysis

“[F]ocusing more phenomenologically on lived experiences can form the basis of sharp critical analysis” (Wright and Patrick 2019: 599). This leads to the possible identification of shared attitudes by precarious workers towards the UEBP and delayed retirement in order to understand its dynamics. Fieldwork to this end was conducted in Sichuan Province from 2020 to 2022. With a purposive sampling and through snowballing recruitment, participants from 68 urban and rural households,[6] aged 24 to 61, were interviewed based on the precarious employment of themselves or their spouses. All participants gave consent before participation.

Table 1 shows their demographic information. Among the participants, 45 were classified as (once) working in public sectors: 15 were former employees in SOEs (including one labour dispatch worker), six were workers in public institutions (including four labour dispatch workers), and 24 were participants (once) in urban public welfare jobs (PWJ, an employment assistance programme providing fixed-term employment contracts with public institutions – e.g., cleaning). The other 23 participants were employed in the private sector as chefs, masseuses, beauticians, welders, mechanics, electricians, or miners, or as self-employed or agricultural workers. The Covid-19 pandemic had caused some to lose work, but all had been in employment regularly or casually. There were no economic thresholds for identifying “precarious workers” for recruitment; however, a minimum income level (not below two thirds of the local average wage) was set in assessing their economic capacity.

Table 1. Demographics of the 68 interviewees

| Age | Household registration | Gender | ||||

| 30 and below | 8 | Rural | 20 | Female | 31 | |

| 31-40 | 7 | Male | 33 | |||

| 41-59 | 52 | Urban | 48 | |||

| Four households, each of these households being treated as one participant, as their interview represents the attitude of their family, with wife and husband both answering. | ||||||

| 60 and above | 1 | |||||

Source: authors.

The interviews were in-depth and semi-structured on topics about employment and life, including social insurance. They included questions such as: “Why did you choose your current job?”, “How long have you already contributed to a pension scheme and why?”, “Do you think enrolling in social insurances is (un)important and why?”, and “What’s your plan(s) on retirement?” The interviews, lasting 45 to 90 minutes, were conducted in Chinese. With participants’ permission, interviews were audio-recorded, or fieldnotes were taken with another research assistant to ensure data accuracy and completeness.

Data collection ended when data saturation was reached, as a way to (re)check data confirmability and credibility. After each interview, preliminary coding was performed to identify important information, adjust follow-up interviews, and evaluate data saturation. After all interviews, data were formally coded in a non-identifiable way, and analysed through abductive thematic analysis strategies, following the steps suggested by Thompson (2022): to move back and forth between inductive and deductive analysis to constantly match and examine theories and empirical discovery.

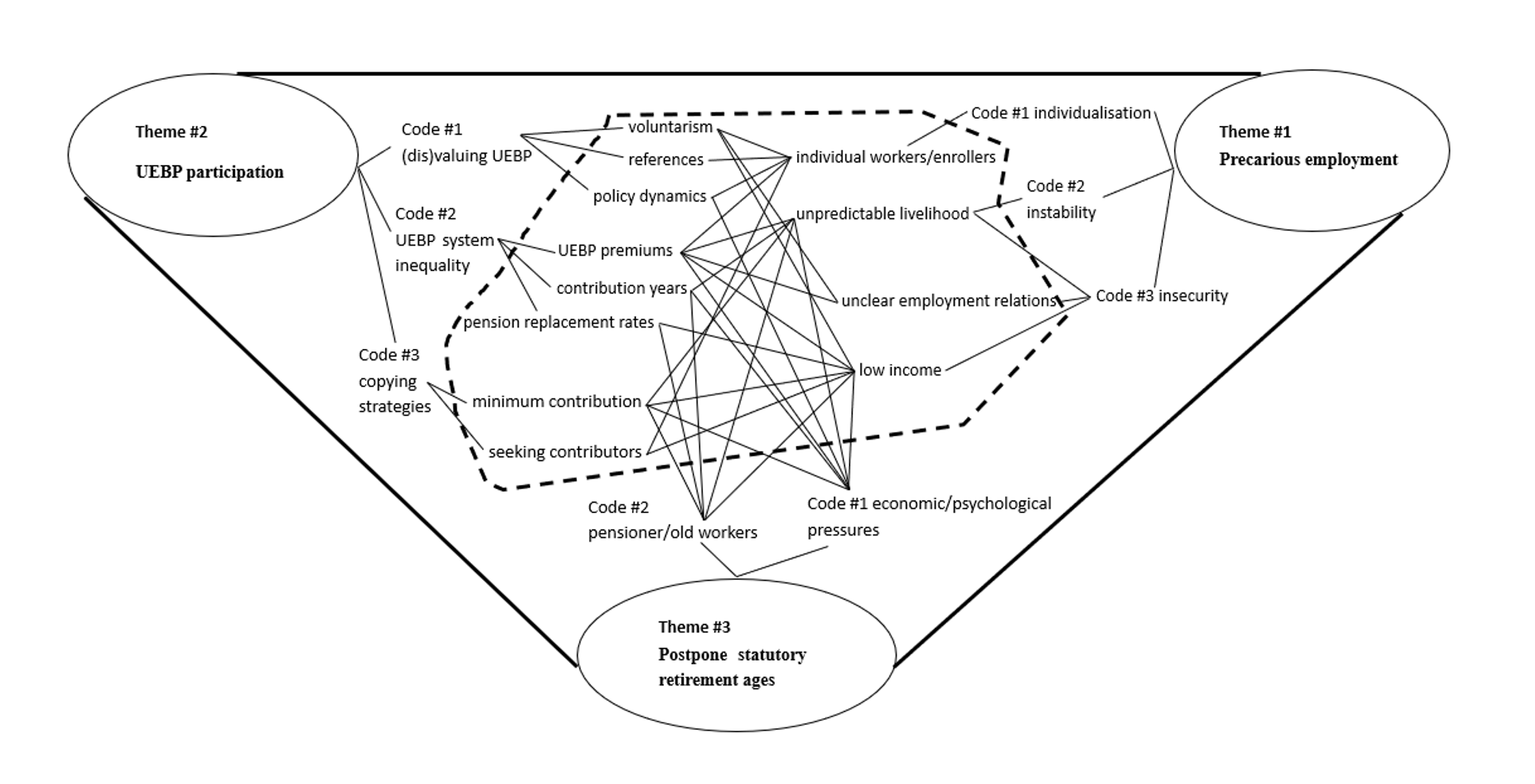

The most important aspects of the raw data were marked as key phrases (within the dashed lines in the figure below), and then summarised or classified into codes and themes (Code #x and Theme #x, respectively). For example, the potential reasons for the code of “(dis)valuing UEBP” were identified as rural background, age, and work-unit experience, yet the comparison showed that work-unit experience was most influential. Therefore, “individual workers/enrollers” was kept in the figure while others were omitted. In this process, the relationships between key phrases were also identified (see the networks in the figure). For example, “individual workers/enrollers” could participate in the UEBP voluntarily (“voluntarism”), had fewer “references” for learning about the UEBP, and were sensitive to “policy dynamics,” which explains why “individualisation” is linked to “(dis)valuing UEBP.”

In abductive thematic analysis, theoretical and empirical knowledge were complementary. For example, the unexpected explanation for the relationship between “individualisation” (a theory-driven code) and “(dis)valuing UEBP” (a data-driven code) was revealed by the corpus, which then generated and was supported by a wider theoretical explanation related to institutions, experience, and cognition. Conducting this iterative process thoroughly and repeatedly established a comprehensive understanding of precarious workers’ UEBP participation and attitudes towards RSRA.

Figure. The network of themes

Source: authors

To protect participants’ privacy and following requests by some interviewees, the full interview transcripts were not shared. The first author coded and analysed data, and the third one double-checked the analysis, as an additional measure to improve research reliability. The relevant extracts[7] were translated into English by the authors.

Precarious workers’ low UEBP participation

UEBP or self-saving? Experience of employment individualisation and knowledge of policy

The experience of individualisation and information asymmetry, rooted in employment but spreading to other aspects of life, has translated into workers’ planning for UEBP. Most participants without a work-unit affiliation, especially those who were younger or lived in rural areas, participated less in the UEBP compared to those who had once worked in a work unit, especially when policy changes (such as those related to participation and retirement eligibility) and employment individualisation cause rejection of, and scepticism towards, the UEBP.

Regardless of their income levels, individual workers tended to devalue the UEBP and preferred self-savings. For example, the 30-year-old rural PWJ RP-5 worked only one week per month without fixed working hours, so she had little interaction with her coworkers in the village committee. She had another part-time job making handmade toys at home. Although she was a “worker” and technically eligible for the UEBP as an individual enroller, she did not enrol but “would rather deposit the money in a bank” (interview, 12 December 2021). Her low wages from the two jobs might be a reason. However, RP-9, who had an annual income of RMB 200,000 to 300,000, also never enrolled (interview with RP-9, aged 30, male, self-employed agricultural worker who ran an orchard).

Although a rural background might be influential, their lack of work-unit engagement should be noted. In contrast to the two above participants, those with greater attachment to work unit(s) had higher trust in the UEBP. For example, UP-6, an urban resident after converting her rural hukou into the urban one about two decades ago, who had work-unit experience and 28 years of UEBP contributions, attributed “higher reliability” to the UEBP’s security than to other public social insurance schemes. While younger age discourages UEBP enrolment, the lack of work-unit engagement is still a significant factor. For example, O-5 (aged 24) admitted: “Anyway, this [enrolling in social insurances] is voluntary (…). I’m so young that I don’t need to buy it (…) until I’m in my thirties or forties” (interview, 16 May 2020 with a female beautician). In comparison with O-5, another relatively young interviewee, (O-2), was more aware of public social insurance. Whereas O-5 had never been employed in a work unit, O-2 had a SOE experience. Therefore, a lack of work-unit experience is more powerful than rural background and age in explaining low interest in UEBP voluntary participation. Individual workers had access to fewer peers who were potential contributors, and thus had less information about the UEBP than those who had worked in a work unit. The near 50-year-old wife of UD-1, a regular worker in the local village committee (and colleague of RP-5), believed that buying public social insurance is necessary because: “Nowadays people all want to buy public social insurance, so I think it is important” (interview, 12 December 2021). Likewise, when asked why she continued to contribute to the UEBP for over three decades, the urban PWJ worker UP-5 said: “I once worked in the factory [a SOE] and started contributions to public social insurance. I kept on doing it even after I had left [the factory]” (interview, 12 February 2022).

Little interaction or lack of affiliation with the pension institution encourages a sense of uncertainty towards institutions. For example, UP-11 (aged 48, with only a few years of work-unit experience from her PWJ and having only seven years of UEBP contributions) claimed that policy dynamics blocked her UEBP participation. When encouraged to consult the authorities about the latest policy, UP-11 refused:

It’s useless to know policy now, [because] the policy is changing, which makes [my action] in vain. So, [let’s] see it later (…). I will ask when [I reach retirement age]. (Interview, 16 February 2022)

The effect of policy dynamics on pension decisions seems different among those with and without work-unit experience. As a work-unit contribution is obligatory, policy modifications have little impact on employees’ pension enrolment, so when they leave the work unit, they have enough information on and confidence in the UEBP to motivate them to continue making contributions if they can afford to do so. In contrast, those who have always been individual workers have had limited contact with people who understand the scheme and are more sensitive to policy uncertainty. Given the lack of clarity regarding the contribution obligations of private employers, as discussed later, they naturally doubted, for example, their eligibility and returns from the scheme.

Insecure employment and access for individual UEBP enrollers

Some participants considered public social insurance as significant for their dignity and future livelihood once they are no longer employable, allowing them to be less of a burden on their children. However, even if they were eligible for the UEBP as individual enrollers and hoped to participate, employment insecurity created by labour service relationships and low pay discouraged their participation.

As mentioned earlier, private employers can legally escape a UEBP obligation through the establishment of a labour service relationship. For instance, the 50-year-old urban PWJ worker P-10 disclosed that her husband did not receive the appropriate public social insurance contribution from his employer:

In the last year when he [the husband] started this job, his boss said he would buy the public social insurance but never did. Later, [the boss] experienced a strict governmental inspection and bought two months of public social insurance. [My husband] did one year’s work but only got two months’ public social insurance! (Interview, 10 April 2020)

These workers did not complain to the authorities but just acquiesced to being deprived of their UEBP enrolment and contributions. This can be explained by the vague definitions of “labour service relations,” which reshape their rationality and deprive them of the ability to participate in the UEBP.

M-3 was laid off from a SOE in the 1990s, so he knew about public social insurance before he became employed as a precarious migrant worker. Almost all of his migrant job employers signed a “contract” but did not buy public social insurance for their workers:

The contract is like a “contract” but not really an [employment] contract (…) [more] like instructions for work. As long as you sign this, you are entered into his or her [the employer’s] records (…) [and this] confirms when you start this job until when you end it (…). [The “contract”] is different from what I signed in factories [in formal sectors] that stipulated buying public social insurance. After all, he or she [the employer in the informal and private sectors] pays you higher wages than the factory (…) meaning they include the cost of your public social insurance contributions. (Interview, 29 February 2020)

M-3 accepted this “contract” form because he regarded his jobs as casual, lasting from several months to a couple of years, and felt that having no contract provided flexibility in changing jobs. Similarly, the 47-year-old urban PWJ worker UP-2 reported that even with a contract, her husband’s employer negotiated with him to sign a letter accepting that he would be paid higher wages in lieu of buying public social insurance.

However, these respondents did not notice that this situation gave them no security and no ability to enrol in the UEBP. The wages they obtained to offset lack of work-unit contributions were not enough to support contributions to the UEBP as an individual enroller. As M-3 explained, he did not self-fund a UEBP account simply because he could not afford it. The gaps in UEBP contribution amounts between those with a work unit and those without were wide. For instance, a work-unit worker with an annual income equal to 60% of the provincial average wage (RMB 41,560)[8] only paid RMB 3,325 (41,560 x 8%); but individual workers should pay at least RMB 6,472 (64,717 x 20% x 50%).[9] The pressure of excessive UEBP contributions for individual workers is another indication of inequality within the public social insurance scheme.

Employment instability and strategies to minimise UEBP self-contributions

Although this analysis accepts that some workers have high wage rates, intervals in employment can lead to instability in economic status. They therefore participate in the UEBP only at the minimum rate level and for the minimum accumulation of years. For example, M-3 noted that intermittent unemployment for more than half the year was the normal situation in his life, and thus even with a wage rate of RMB 200-300 per day, his annual income was low. People such as M-3 were unable to predict their future income. When considering lifelong income, they spent earnings cautiously in their best years. Whatever their income levels, respondents usually said “[I/We] cannot earn [enough] money” or “no money.” It is not that they really had no money, but that they worried about having no money someday, since their job and their source of income was unstable. Therefore, rather than consistently contributing a large proportion of their money to the UEBP, they chose to reduce their current expenditure in case of any unexpected substantial expense. M-7, a 48-year-old male chef, who used to be a migrant worker, had had an income of RMB 7,000-10,000 per month and had contributed to the UEBP for more than a decade before becoming jobless for three months, makes this point:

[My personal expenditure is] about 1,000 yuan [monthly] (…) I shouldn’t spend all I earn (…) I don’t have a formal [job] (…) I must save some money (…) for old age (…) and in case of any disease. (Interview, 12 March 2020)

The retrenchment would become rather significant when involving the interests of their family. For example, UP-11 explained not purchasing a higher level of public social insurance in this way: “We need to support children. It’s impossible [for us] to use all our money to buy public social insurance. We must consider the children.” (Interview, 16 February 2022). Nonetheless, because these participants valued public social insurance, they tried to contribute as much as possible. A common way was to seek a work-unit contributor, as exemplified by a chef (M-6), aged 29, who as an individual worker did not buy into the UEBP. He planned to go to work in a government canteen in his forties, even though the wage might be lower than his current work. After observing many of his older coworkers, he assumed that, as a law-regulated work unit, a government canteen would buy public social insurance for him.

Similarly, some participants undertook PWJs when they neared retirement age, primarily because they could obtain a work-unit contribution to their public social insurance. PWJs provided subsidies only at the local minimum wage level. Eligible applicants before retirement could stay on welfare for three to five years. These jobs were usually simple or unskilled tasks, unlikely to match the skills of some applicants. The programme attracted many middle-aged precarious workers who had a higher income but no public social insurance contributions from their employer. For example, UP-5 chose a PWJ, even though previously she had earned at a higher rate than local average levels, because: “I considered that this job [PWJ] also supplies me with public social insurance. Otherwise, 1,280 yuan [her subsidies] is too low.” (Interview, 12 February 2022)

UP-4 claimed that without public social insurance she would never do a PWJ:

If it didn’t provide public social insurance, nobody would be willing [to do PWJs]. Put yourself in my shoes, [if I] ask you [to do this job] with such a low wage, would you take it? You will refuse. (Interview, 11 February 2022, with UP-4, a 46-year-old urban PWJ worker)

These examples suggest that workers either contributed to the UEBP at a minimum level as individual enrollers, or they waited for an appropriate time to transfer this economic commitment to a work unit, even if it meant lower wages.

The likely impact of RSRA on precarious workers

Given the nature of precarious employment and the difficulties in UEBP participation, economic challenges and pressures during precarious employment will likely have an impact on the period of retirement. RSRA is likely to reduce freedom in workers’ retirement arrangements, extending precarity and inequality in their lives.

When asked about their retirement plans, most participants remarked that they would continue to work if physically capable. Twelve of the households were involved in bridge employment. Some were working to keep healthy and fill their time, but for those who had accumulated little wealth during employment, receiving a pension (while still working) provided relief both economically and emotionally.

For example, T-1 (aged 47) had a full-time job in a company as a cleaner, with wages of about RMB 1,500 per month after contributing to public social insurance, doing occasional part-time jobs. Her husband had a PWJ with a disposable income of about RMB 1,300 per month, after being laid-off from a SOE and working as a precarious worker. She was unsure of when she would retire because of the potential policy of RSRA. At the time of the interview, her husband had just reached the current statutory retirement age and submitted his application for retirement.

During most of the interview, T-1 exhibited negative emotions when talking about jobs and life. Her depression appeared to be caused by issues such as their high-school daughter’s education fees, her husband’s illness, which she attributed to the huge pressure and anxiety from precarious employment, and their downward socioeconomic status from SOE formal workers to the “bottom” (her words) as precarious workers. Those worries were based on income limitations that prevented her from enjoying social activities and even visits to close relatives. When asked for her comments, she stated:

Where is justice? (…) I feel dissatisfied with my entire life (…). People despise (…) those who don’t have a good life (…). My pressure [is huge] (…) I feel inferior in my heart, but [I] adjust. (Interview, 14 January 2020)

Nonetheless, when chatting about her husband’s retirement, T-1’s emotions appeared more positive. As her husband had long-term UEBP contributions due to his long employment history in work units, she calculated that he would have a pension of RMB 3,900 per month: “My husband retired, [and] I feel a lot more relaxed.”

T-1’s household is fortunate, as precarity and inequality in employment could be recouped by steady higher income in retirement. However, other precarious workers may not have the same situation. As already outlined, some workers had made low or minimum contributions. The return for a 15-year contribution with the lowest premium, based on five pensioner workers’ reports, was around RMB 1,000+ per month. For those having relatively high employment incomes, this amount of pension plus their savings could maintain their lifestyle; but low-income workers with minimum contributions were very likely to become pensioner workers, more out of need than choice, and continued suffering inequality in their old age, even when precarity could be reduced by receiving a pension. Furthermore, the most disadvantaged group were low-income workers who did not meet pension eligibility when reaching the statutory retirement age. Their precarity and inequality in employment might be extended into their old age, as they were not even considered pensioner workers but simply older workers. UP-7 (aged 54), for example, had disposable income from employment of around RMB 1,200 per month and had only a couple of years of UEBP contributions. Before taking a PWJ, she did not buy public social insurance because her income was inadequate for the self-funded scheme. When discussing retirement, she said: “I may not [retire] until 60 years old [under the new policy] (…). [If the pension] money is not enough for living (…) I would seek another job.” (Interview, 14 February 2022). She was largely unaware that she could not receive a pension because she would have less than 15 years’ contributions when she turned 60. This gave her three choices: (a) continuing to pay premiums after she turns 60 years old; (b) transferring the UEBP to the pension scheme for urban and rural residents, which, in Sichuan in 2021, provided a pension averaging only RMB 105 per month;[10] (c) cashing out of the schemes and seeking another source of livelihood in her old age. For workers such as UP-7, whether or not RSRA is implemented, appropriate security in later life is a problem regardless of the three options.

Undeniably, according to pension calculation rules, if precarious workers maintain the minimum contribution rates and years, then RSRA can hardly increase their economic security in later life. Rather, RSRA means more pressure in meeting UEBP premiums and a delay in receiving a pension. For individual enrollers, the baseline for contribution is not their wages but the local average wages, where the average increment likely exceeds the income increases of most precarious workers. Some interviewees reported that public social insurance fees increased from RMB 5,000 to near 20,000 in a dozen years, while their wages seemed to stagnate.

Moreover, when those workers approach retirement age, their economic capacity is likely to decrease dramatically. Some middle-aged participants have taken a PWJ because they could not find a better job in the labour market. Turning 40 and 50 “in the current Chinese context is considered too old and unsuitable for many jobs” (Gao 2017: 84). If the statutory retirement ages are raised, earning money will likely become harder for people as they age, increasing the burden of their contributions.

Furthermore, delaying retirement means a prolonged precarious employment period and subsequently more life uncertainty. In the current situation, a pensioner’s active role in the labour market does not prevent him or her from receiving a pension (Xie et al. 2021). Pensions are additional money so that older workers in precarious employment can be less worried about their source of livelihood if they lose their jobs. This is especially important when middle-aged parents financially support members of their younger generation’s nuclear family who are often also in a precarious employment situation. Providing intergenerational support was another reason for bridge employment.

Taking care of grandchildren was another way that middle-aged parents supported their children’s family. RSRA may create a barrier to doing so. In particular, female workers are likely impacted more than their male counterparts, given their role as caregivers in the family. Some middle-aged skilled workers had higher wages than younger, unskilled workers, so RSRA might negatively affect the availability of the older generation to their family, and their access to income from bridge employment. However, when a mother could earn more than a grandmother due to younger age, RSRA can involve a significant financial loss and put more pressure on male members. The vicious circle of intra-household precarity is thus likely to be aggravated.

In addition, some participants hoped to retire as soon as possible because of poor health. With even a low pension, they could work less, but could not fully exit the labour market without fretting about their basic livelihood.

Hence, given the reduced freedom to choose their time of retirement and the longer periods of uncertainty and pressure they have to endure, workers in precarious employment were disadvantaged by RSRA.

Discussion and conclusion

Studies in other countries have shown that employers increasingly create precarious jobs where they promise to empower workers with more freedom; however, because of insecurity, the proposed individual agency and liberation just puts even relatively privileged workers into greater dependence and powerlessness (Chan 2013). Likewise, it was evident in the context studied that precarious employment can cause chronic marginalisation of workers in relation to employment, pensions, and retirement.

This article has developed a sociological framework to analyse China’s normalised precarious employment and its effects expanded by pension and retirement policies. Through a review of literature and the field research conducted, the framework highlights three features of China’s precarious employment (individualisation, insecurity, and instability), and their underexplored consequences in (a) experience and cognition, (b) institutionalised inequality, and (c) the extension of precarity and inequality from employment into retirement. In a word, the research reveals that labour market regulations, and pension and retirement policies are not well coordinated and often increase the inequality that precarious workers face.

Showing how precarious employment limits workers’ UEBP participation and why this situation is likely to deteriorate with RSRA, this research speaks to the disputes around workers’ reactions to employment reforms and the (in)equality of public policy in contemporary China. While a few embraced the flexibility and convenience of job-hopping, the workers interviewed in this research generally regarded precarious employment as a risk and feared it could lead to insufficient funds to maintain their livelihood. This somewhat argues against scholars who see precarious employment as a phenomenon related to freedom and sustainable livelihood (Huang, Zhang, and Xue 2018), or against some younger workers in the digital economy who associate insecure and uncertain employment with time autonomy, self-decision, and transitional choice (Sun and Chen 2021). Compared with the influence of the Covid-19 pandemic, which might enhance workers’ negative attitudes towards employment and life, the dissimilarity might be explained by the age brackets of workers, the experience before being in precarious employment, or the industries participants worked in. In any case, it is too early to link precarious employment to freedom or autonomy for these workers, especially when it is related to social reproduction – pension, retirement, and bridge employment in this article.

The worker pension and retirement strategies analysed also enhance the literature on how precarity and inequality become “lifelong” through the UEBP. The result of this study suggests that precarious workers tend not to enrol in the UEBP until midlife, at which time they would seek a work-unit enroller to minimise the burden of paying premiums, or they maintained a minimum contribution as self-funded individual enrollers. Due to their low levels of UEBP contributions, they are likely to experience precarious funding in retirement with little or no pension, and therefore become older workers or pensioner workers.

Consistent with the claim that long-standing institutions such as the work-unit system, and increased uncertainty in the labour market, are greater factors than education or income level in determining workers’ reaction to pension reform (Frazier 2010: 144), the present research found that those with little work-unit attachment trusted self-saving more than the UEBP. Detachment from a formal work relationship with an enterprise, individualised employment, and other related aspects appeared to cause rejection of information on, and scepticism towards, public and governmental protection. This does not deny information sharing and reciprocity among their colleagues (Peng 2022). The issue is that when unclear definitions of “labour relationships” and “service relationships” rationalise employers’ UEBP obligation exemption, coworkers who are also precarious workers may likewise have little interaction with the UEBP, so their information sharing may be less likely related to the UEBP. As for individual enrollers, if intervals between employment become frequent, their incomes (even high wages) are neither stable enough nor sufficient for them to pay UEBP premiums.

Delaying mandatory retirement for workers in precarious employment is likely to result in a longer period of unpredictability and instability, and thus more insecurity and anxiety. When increasing the UEBP contribution burden, such workers will not receive a larger pension because of the rules used to calculate the UEBP. Instead, they would have less freedom to manage a retirement life but more worries about their livelihoods. Similar to findings focusing on migrant labour dispatch workers (Feng 2019), this study found that most middle-aged participants experienced serious age discrimination in the job market. Research in another country has reported that, for lower-income households, the increased employment income from delayed retirement cannot compensate for the income loss from not receiving a pension (Cribb and Emmerson 2019). In China, the situation is likely to be similar. Hence, retirement deferment to encourage later working in an ageing society is likely to be disadvantageous to the 50+ workforce, which experiences a shift from government responsibility for the financial security of the labour market to self-security (Flynn and Schröder 2021).

Taking precarious employment into account, the underpinning rationales for RSRA seem questionable. The existence of pensioner workers likely weakens the credibility of RSRA increasing the workforce (Xie et al. 2021). And actuarial results suggest that RSRA may not be an optimal measure for the UEBP’s long-term finance balance (Jing et al. 2021; Yuan 2022).

Taking these findings all together, a salient policy implication is that implementing the RSRA policy should work in tandem with modifications to both labour market and UEBP regulations. At least three issues require rigorous debate. The first is to clarify the “service relationship” and “labour relations” in the employer-employee relationship, especially when no work unit is involved, in order to expand UEBP coverage and other kinds of labour protection.

The second issue is the compulsory enrolment of individual workers in the UEBP. Employers’ significant influence on employees’ perception of and ability to enrol in the pension scheme has been confirmed. In some countries, in order to mitigate the problem of little interest in pension saving, the employer is made responsible for automatically enrolling their eligible employees in a suitable pension scheme; the employee then can decide to participate or exit. This approach was evaluated as being effective for young people’s commitment to pension schemes (Collard 2013). This might be a good example for the UEBP to learn from, especially given the role the UEBP plays in “deferred wages.”

The third concern is UEBP contribution premiums. In a so-called partially funded system, individual enrollers have to comply with a fully individual fund. The UEBP could subsidise individual enrollers so that the concept of “deferred wages” could be applied to them in a different way. Equally, individual enrollers have a UEBP contribution base and rate higher than the standard (Yuan 2022: 72-5), which reinforces workers’ vulnerability. Reducing premiums would be conducive to their pension participation. Ongoing research should investigate the possible effects of these measures, especially by expanding the range of precarious workers to be examined.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on the manuscript. Thanks to Xiaolin Li and Peiling Luo of Wuhan University for their assistance in language and comments on the early draft of the manuscript. The work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China under Grant No. 23CSH057.

Manuscript received on 3 October 2023. Accepted on 6 May 2024.

References

ALLEN, John, and Nick HENRY. 1997. “Ulrich Beck’s Risk Society at Work: Labour and Employment in the Contract Service Industries.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 22(2): 180-96.

ASHWIN, Sarah, Katherine KEENAN, and Irina M. KOZINA. 2021. “Pensioner Employment, Well-being, and Gender: Lessons from Russia.” American Journal of Sociology 127(1): 152-93.

BIKHCHANDANI, Sushil, David HIRSHLEIFER, and Ivo WELCH. 1992. “A Theory of Fads, Fashion, Custom, and Cultural Change as Informational Cascades.” Journal of Political Economy 100(5): 992-1026.

CAMPBELL, Iain, and Robin PRICE. 2016. “Precarious Work and Precarious Workers: Towards an Improved Conceptualisation.” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 27(3): 314-32.

CHAN, Chris King-Chi, and Elaine Sio-Ieng HUI. 2023. “Pension Systems and Labour Resistance in Post-socialist China and Vietnam: A Welfare Regime Analysis.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 53(2): 233-52.

CHAN, Sharni. 2013. “‘I am King’: Financialisation and the Paradox of Precarious Work.” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 24(3): 362-79.

CHOW, Nelson, and Yuebin XU. 2018. “Pension Reform in China.” In Catherine Jones FINER (ed.), Social Policy Reform in China: Views from Home and Abroad. London: Routledge. 129-42.

COLLARD, Sharon. 2013. “Workplace Pension Reform: Lessons from Pension Reform in Australia and New Zealand.” Social Policy and Society 12(1): 123-34.

CRIBB, Jonathan, and Carl EMMERSON. 2019. “Can’t Wait to Get My Pension: The Effect of Raising the Female Early Retirement Age on Income, Poverty and Deprivation.” Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 18(3): 450-72.

DETTMERS, Jan, Stephan KAISER, and Simon FIETZE. 2013. “Theory and Practice of Flexible Work: Organizational and Individual Perspectives: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Management Revue 24(3): 155-61.

DONG, Keyong, and Gengyu WANG. 2016. “China’s Pension System: Achievements, Challenges and Future Developments.” Economic and Political Studies 4(4): 414-33.

DONG, Yige. 2020. “Spinners or Sitters? Regimes of Social Reproduction and Urban Chinese Workers’ Employment Choices.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 61(2-3): 200-16.

FENG, Xiaojun. 2019. “Trapped in Precariousness: Migrant Agency Workers in China’s State-owned Enterprises.” The China Quarterly 238: 396-417.

FLYNN, Matt, and Heike SCHRӦDER. 2021. “Age, Work and Pensions in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong: An Institutional Perspective.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 42(2): 248-68.

FRAZIER, Mark W. 2010. Socialist Insecurity: Pensions and the Politics of Uneven Development in China. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

FURUNES, Trude MYKLETUN, Per Erik SOLEM, Annet de LANGE, Astri SYSE, Wilmar B. SCHAUFELI, and Juhani ILMARINEN. 2015. “Late Career Decision-making: A Qualitative Panel Study.” Work, Aging and Retirement 1(3): 284-95.

GAO, Qin. 2017. Welfare, Work, and Poverty: Social Assistance in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

GOLDBERG, Renada M., and Catherine A. SOLHEIM. 2021. “Family Stress and Coping in the Experience of Employment Precarity: A Theoretical Framework.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 13(4): 411-27.

GUO, Yu, Mo TIAN, Keqing HAN, Karl JOHNSON, and Liqiu ZHAO. 2016. “What Determines Pension Insurance Participation in China? Triangulation and the Intertwined Relationship among Employers, Employees and the Government.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27(18): 2142-60.

HUANG, Gengzhi, Hong-ou ZHANG, and Desheng XUE. 2018. “Beyond Unemployment: Informal Employment and Heterogeneous Motivations for Participating in Street Vending in Present-day China.” Urban Studies 55(12): 2743-61.

HUANG, Philip C. C. 2009. “China’s Neglected Informal Economy: Reality and Theory.” Modern China 35(4): 405-38.

IMMERGUT, Ellen M. 1998. “The Theoretical Core of the New Institutionalism.” Politics & Society 26(1): 5-34.

INGRAM, Paul, and Karen CLAY. 2000. “The Choice-within-constraints: New Institutionalism and Implications for Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 26(1): 525-46.

IRVINE, Annie, and Nikolas ROSE. 2024. “How Does Precarious Employment Affect Mental Health? A Scoping Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence from Western Economies.” Work, Employment and Society 38(2): 418-41.

JIANG, Jin, Jiwei QIAN, and Zhuoyi WEN. 2018. “Social Protection for the Informal Sector in Urban China: Institutional Constraints and Self-selection Behaviour.” Journal of Social Policy 47(2): 335-57.

JING, Peng, Cai CHANG, Heng ZHU, and Qiuming HU. 2021. “Financial Imbalance Risk and its Control Strategy of China’s Pension Insurance Contribution Rate Reduction.” Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5558757

KALLEBERG, Arne L. 2009. “Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition.” American Sociological Review 74(1): 1-22.

KIM, Yun-Young, Seung-Ho BAEK, and Sophia Seung-Yoon LEE. 2018. “Precarious Elderly Workers in Post-industrial South Korea.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48(3): 465-84.

LEE, Ching Kwan. 2019. “China’s Precariats.” Globalizations 16(2): 137-54.

LEE, Ching Kwan, and Yelizavetta KOFMAN. 2012. “The Politics of Precarity: Views Beyond the United States.” Work and Occupations 39(4): 388-408.

LIU, Tao, and Li SUN. 2016. “Pension Reform in China.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 28(1): 15-28.

MENG, Ke. 2019. China’s Pension Reforms: Political Institutions, Skill Formation and Pension Policy in China. London: Routledge.

MOK, Ka Ho, and Jiwei QIAN. 2019. “A New Welfare Regime in the Making? Paternalistic Welfare Pragmatism in China.” Journal of European Social Policy 29(1): 100-14.

NG, Lilian, and Fei WU. 2010. “Peer Effects in the Trading Decisions of Individual Investors.” Financial Management 39(2): 807-31.

NIESEL, Christoph, Laurie BUYS, Alireza NILI, and Evonne MILLER. 2022. “Retirement Can Wait: A Phenomenographic Exploration of Professional Baby-boomer Engagement in Non-standard Employment.” Ageing and Society 42(6): 1378-402.

PENG, Xinyan. 2022. “‘You Cannot Make Friends at Work’? Relatedness in and beyond the Workplace and the Reconfiguration of Kinship and Gender in Urban China.” Modern China 48(6): 1265-93.

PETRACCA, Enrico, and Shaun GALLAGHER. 2020. “Economic Cognitive Institutions.” Journal of Institutional Economics 16(6): 747-65.

PUN, Ngai, Peier CHEN, and Shuheng JIN. 2024. “Reconceptualising Youth Poverty through the Lens of Precarious Employment during the Pandemic: The Case of Creative Industry.” Social Policy and Society 23(1): 87-102.

ROBERTSON-ROSE, Lynne. 2019. “Good Job, Good Pension? The Influence of the Workplace on Saving for Retirement.” Ageing and Society 39(11): 2483-501.

SI, Jinghui. 2024. “Higher Education Teachers’ Professional Well-being in the Rise of Managerialism: Insights from China.” Higher Education 87(4): 1121-38.

STANDING, Guy. 2008. “Economic Insecurity and Global Casualisation: Threat or Promise?” Social Indicators Research 88(1): 15-30.

——. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

SUN, Ping, and Julie Yujie CHEN. 2021. “Platform Labour and Contingent Agency in China.” China Perspectives 124: 19-27.

SUN, Qixiang, and Lingyan SUO. 2007. “Pension Changes in China and Opportunities for Insurance.” The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance. Issues and Practice 32(4): 516-31.

TANG, Jun 唐均. 2002. “非正規就業不可避免” (Fei zhenggui jiuye bu ke bimian, Informal employment cannot be avoided). Zhongguo gaige (中國改革) 12: 45-6.

TAPPOLET, Christine. 2016. Emotions, Values, and Agency. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

THOMPSON, Jamie. 2022. “A Guide to Abductive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Report 27(5): 1410-21.

WANG, Huan, and Jianyuan HUANG. 2023. “How Can China’s Recent Pension Reform Reduce Pension Inequality?” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 35(1): 37-51.

WRIGHT, Sharon, and Ruth PATRICK. 2019. “Welfare Conditionality in Lived Experience: Aggregating Qualitative Longitudinal Research.” Social Policy and Society 18(4): 597-613.

XIE, Lin, Yuan-yang WU, Ying-xi SHEN, Wen-chao ZHANG, An-qi ZHANG, Xue-yu LIN, Shi-ming TI, Yi-tong YU, Hualei YANG. 2021. “Effect of Retirement on Work Hours: Evidence from China.” Social Indicators Research 157: 671-88.

YUAN, Randong. 2022. Pension Sustainability in China: Fragmented Administration and Population Ageing. London: Routledge.

ZHAO, Chuanmin, and Xi QU. 2021. “Peer Effects in Pension Decision-making: Evidence from China’s New Rural Pension Scheme.” Labour Economics 69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2021.101978

ZHAO, Qing 趙青. 2023. “基于合理繳費負擔的靈活就業人員社會保險參保路徑研究” (Jiyu heli jiaofei fudan de linghuo jiuye renyuan shehui baoxian canbao lujing yanjiu, Extending social insurance coverage to flexible workers based on a reasonable contribution burden). Shehui baozhang pinglun (社會保障評論) 7(02): 94-108.

ZHOU, Ying. 2013. “The State of Precarious Work in China.” American Behavioral Scientist 57(3): 354-72.

ZHU, Huoyun, and Alan WALKER. 2018. “Pension System Reform in China: Who Gets What Pensions?” Social Policy & Administration 52(7): 1410-24.

[1] National Bureau of Statistics of China (eds.), 2023, China Statistical Yearbook 2023, Beijing: China Statistics Press.

[2] The UEBP originally targeted urban enterprises. With reform of the labour market and pension institutions, although still called “urban,” eligibility is not affected by employment in an urban versus a rural zone.

[3] “Informality and Non-standard Forms of Employment,” International Labour Organization, 2 October 2018, https://www.ilo.org/publications/informality-and-non-standard-forms-employment-0 (accessed on 28 January 2021).

[4] Labour service relations (laowu guanxi 勞務關系) is a kind of employee-employer relationship in which the employee provides service to the employer but there is no formal labour relationships (laodong guanxi 勞動關系) between them.

[5] Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Sichuan Province 四川省人力資源和社會保障廳,

“2021年四川省人力資源和社會保障事業發展統計公報” (2021 nian Sichuan sheng renli ziyuan he shehui baozhang shiye fazhan tongji gongbao, Statistical bulletin of human resources and social security development in Sichuan Province in 2021), http://rst.sc.gov.cn/rst/ghtj/2022/7/19/3ac847eeb00f438b8dd65bdb40b1ca23.shtml (accessed on 2 December 2022).

[6] Another four households were excluded because all nuclear family members living together had exited the labour market.

[7] We grouped the interviewees in different categories according to their status. This is why in the article, codes such as RP-x, UP-x, O-x, T-x, P-x, and M-x are cited where the relevant cases are involved.

[8] The average wage of Sichuan Province was RMB 69,267 in 2019, a year before the first fieldwork was conducted.

[9] Normally, the contribution base for individual enrollers should be between 60% and 300% of provincial average wages in the previous year. However, because of Covid-19, the lowest standard of contribution base was 50% of the provincial average wage in 2018 (RMB 64,717).

[10] Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Sichuan Province 四川省人力資源和社會保障廳, “2021年四川省(…),” op. cit.