BOOK REVIEWS

The Shaping of “New Gentry” Discourse in the Context of China’s Rural Revitalisation and Heritage Conservation Strategy

Ruyu Tao is a PhD candidate at both City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, and Tianjin University, No. 92 Weijin Road, Nankai District, Tianjin, 300072, China (taoruyu1@gmail.com).

Pinyu Chen is Lecturer and Outstanding Young Scholar in the School of Social Science at Soochow University, No. 199 Ren’ai Road, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu, 215123, China (pychen66@suda.edu.cn).

Nobuo AOKI is Professor at the School of Architecture at Tianjin University, No. 92 Weijin Road, Nankai District, Tianjin, 300072, China (nobuoak@gmail.com).

Introduction

Rural revitalisation has been formulated as a national strategy in China in recent years, and under extensive experimental discussion aims to achieve balanced development between rural areas and cities in the context of rapid urbanisation and continuous decline of rural areas.

The redevelopment or reuse of cultural heritage sites in rural areas has become a potentially viable strategy for rural revitalisation lately, and is consistent with UNESCO’s principles for the sustainable development of cultural heritage.[1] With the redevelopment of cultural heritage and revitalisation of traditional culture, professional and official voices in China have increasingly reintroduced the concept of a particular group, “gentry” (xiangshen 鄉紳or xiangxian 鄉賢), in anticipation of its role in rural development, tracing back to the imperial period (Wittfogel 1955: 404-5; Zhang Z. 1955; Watson 1982). The rationale for this concept stems from the significant role of local gentry groups and elites in rural areas’ regional autonomy – conservative traditional small-scale farming economy, Confucian culture, and ideological norms – a “harmony” (hexie 和諧) status governed and led by local elites (Fei 1992). In the current social and economic context, the reestablishment of the notion of gentry in the countryside is accompanied by the systematic restoration of traditional buildings, establishment of private estates, inflow of capital, and intervention of elite groups and organisations. As this phenomenon occurs in contemporary society, we hereby refer to this particular group as the “new gentry.”

We selected Xixinan Village (Anhui Province) as a case study, focusing on the antinomy of the discourse in the process of shaping the new gentry group. We aim to interpret and answer the following questions: (1) How does the elitism of the gentry management system achieve legitimacy in the modern socialist society and how does it operate? (2) In the context of continuous privatisation and class differentiation in rural areas (Zhang Q. 2015: 343-4), how does the reuse of heritage echo the official discourse on the overall social transformation of contemporary China, and what potential risks and controversies does it entail?

We argue that curating the new gentry notion reflects a legitimisation of large-scale entry of private capital into rural areas and the privatisation of rural land and other assets. This process has received considerable support and acquiescence from local governments, and through it, the discourse on power and privileges among elite groups is gradually constructed. The restoration and redistribution of traditional buildings and heritage sites have been used to attract investors (Cooke 2018: 44). By doing so, it consolidated a local management structure of elites, landlords, and local bureaucrats in historically rural areas, brought urgently needed funds to rural governments, promoted the overall vitality of economic development, beautified the environment, and generated employment. This has effectively promoted community participation and enthusiasm for the reuse of historical areas and heritage sites (Hodges and Watson 2000). In addition, by extracting the concept of “harmony” from traditional culture, the official discourse can be effectively passed through the “traditional culture revival” (chuancheng hongyang Zhonghua youxiu chuantong wenhua 傳承弘揚中華優秀傳統文化) movement, in that way joining with various stakeholders in accelerating the reutilisation of cultural heritage. According to Herzfeld (2016: 11-8), this avoids public opinion controversies and promotes acceptance among original residents of the interventions by incoming elites. This topic requires critical theoretical thinking from a broader scope instead of being limited to ontological heritage research (Waterton and Watson 2013: 547). Therefore, we analyse concepts and theories from the dual perspectives of heritage and policy research – in combination with a case study – to interpret the importance and contradiction inherent in the new gentry notion and relevant groups in heritage development.

Literature review

The management system in imperial Chinese rural areas relied to a considerable extent on the local gentry who had the rights and responsibilities of managing relevant affairs. They had official authority as residents’ spokespeople and advisors to the local government and might receive various economic, honour, taxation, and legal privileges (Fei 1992). This reciprocal system, also endorsed by Confucianism, was centred on ethics and lineage since the Song and Yuan dynasties (McDermott 2013: 25-32). The gentry group therefore had a stabilised position with flexibility and variation in terms of occupation rather than being merely landlords or bureaucrats (Esherick and Backus Rankin 1990: 13-9). This was maintained through education, etiquette, and custom, rather than laws and violence (Fei 1953; Watson 1982: 601-6). This system had a far-reaching influence, even after the collapse of imperial society, until the early twentieth century. However, the gentry’s influence over local affairs also had the potential to facilitate opposition to the government, for example in the late Ming (Miller 2008). Thus, the power between the government and the local gentry was counterbalanced (Yang 2018).

After 1949, the Chinese Communist Party launched the Land Reform Movement, which eliminated the traditional gentry class and redistributed land to peasants (Fairbank and MacFarquhar 1987: 85-7). However, industrialisation redistributed privileged status to the urban minority, including the elites, while the rural majority was responsible for providing raw materials for capital accumulation through industrial processes in urban areas (Shue 1980; Davis 2000). Despite these changes, “class differentiation” was not eliminated. Current research on the gentry ends abruptly after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, and there is a lack of clear investigation into whether this group has disappeared or undergone transformation.

Since 2010, domestic Chinese academia has renewed its concern regarding the gentry in reference to rural development. Some introduced the notion of the new gentry, which initiated the cultivation of an elite group for rural governance (Zhang and Zhang 2014; Xiao and Ma 2018), and claimed that the imperial period experience could be refined and applied directly to promoting contemporary local autonomy (Cao and Zhang 2017). The new gentry have also been declared the essential executors and leaders in the rural revitalisation strategy from the national to local level.[2] In their study on gentrification in Hong Kong, Ley and Teo (2014) found that the terms “becoming rural gentry” (xiangshen hua 鄉紳化) or “the gentry in the villages/countryside” (xiangshen 鄉紳) were rarely used by the medias. This emerging logic and its correlation with multisubject discourse require further investigation.

Although this article uses the term new gentry to describe the phenomenon of the emergence of new rural groups, it differs from gentrification. Rural gentrification in Western countries usually involves leisure consumption and entertainment activities by high-paying urbanites in rural areas (Bessière 1998; Nelson and Nelson 2011). It is also described as a form of “amenity migration” (Alonso González 2017). However, as Ghertner (2015) submits, much research treats gentrification as the process by which private property becomes the dominant form of ownership without considering specific conditions. Ley and Teo (2020) caution against defining or taking sides on gentrification issues. Besides, the relevance of the term gentrification is questionable in many non-Western regions (Ley and Teo 2014). Rural gentrification has led to significant changes including informal behaviour and land systems in rural areas (Zhao 2019) and the redevelopment of historical areas (Zhu and González Martinez 2022), thus attracting research attention (Zhang et al. 2022). It may not harm local villagers, but allows coexistence with outsiders (Chen, Zhang, and Wang 2024). Although this study focuses on discursive construction, the research is related to rural gentrification, and given that the term new gentry has been coined to describe it, it is necessary to clarify the specific causes of the emergence of this group.

Research context and method

This study is based on theoretical and practical discourse analysis. The village of Xixinan, which is located in Huangshan City, Anhui Province, and is within a three-hour drive from both Shanghai and Hangzhou, was selected as a case study. Xixinan is one of the richest areas in Huizhou District, itself known for its so-called Hui-style (huipai 徽派) villages and architecture. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, Xixinan was home to numerous wealthy Huizhou merchants and celebrities. Today, it features a lot of vernacular historical remains, including buildings and cultural landscapes, and is considered a typical Hui-style village in eastern China (Lu, Chen, and Fu 2022). Urbanisation has caused a drastic economic decline in the village, threatening its historical heritage and inhibiting development. Nevertheless, the investment and intervention of new immigrants (xin yimin 新移民) (Chen and Kong 2021: 694) – represented by the new gentry – have drastically changed the overall situation.

Figure 1. Public pavilion and water canal in the centre of Xixinan Village, July 2021. This is a classical scene of a Hui-style village in eastern China, characterised by an abundance of water and a quiet, cosy ambience.

Credit: authors.

We conducted several field investigations and interviews from the Spring Festival of 2020 to March 2022. To access reliable data and first-hand information, our sources included official documents, manuscripts, news reports, propaganda materials, and interviews with residents and stakeholders. We applied a non-participatory observation approach to the research fieldwork. We selected 14 people from different backgrounds and professional sectors for semi-structured and open-ended interviews; some were interviewed multiple time to ensure clarity. The interviewees were divided into four main categories according to their status: A (local farmers), B (new gentry, including migrants and investors), C (local officials and scholars), and D (local NGO members and cultural enthusiasts). All names were replaced with codes to ensure anonymity. The interviews aimed at soliciting the opinions of subjects from diverse identities, positions, and interests, and demonstrating varied perceptions and attitudes towards the influence of new gentry groups in the context of a broader rural revitalisation.

The shape of new gentry discourse

Revitalise the countryside: The introduction of a modern gentry-oriented system

Since the implementation of China’s reform and opening up policy, the income and development gaps between rural and urban areas have been continuously expanding. The urban-rural inequality ratio has become the most important factor in the intensification of income inequality in China (Jain-Chandra et al. 2018); inequality in rural areas is higher than that in cities. Urbanisation and increasing urban-rural inequality have led to an influx of rural populations into cities. While this provides “blood transfusions” for cities, this labour force from rural areas is facing serious exploitation and is restricted by the household registration (hukou 戶口) system (Gu and Shen 2003). The prevailing situation in contemporary rural areas is that, after decades of population loss, they no longer have effective and sustainable self-productive capabilities. More importantly, the government did not permit rural real estate transactions, hindering rural property appreciation compared to that of urban areas (Li and Fan 2020: 3). As a result, rural areas face a shortage of young workers and funds. Remittances, rather than wages, from cities to rural areas are essential for the livelihood of rural residents.[3] The background of class and urban-rural differentiation, and rural economic decline with the lack of younger workforce lay the foundation for the introduction of the new gentry notion.

Since the start of the “Construction of a New Socialist Countryside” (shehui zhuyi xin nongcun jianshe 社會主義新農村建設) movement in 2005, the state aimed to enhance a “civilised lifestyle,” ensuring a tidy environment and democratic administration in the countryside (Thøgersen 2009: 10). Additionally, under the guidance of “economy first,” the central government partially granted power at the local level to entrusting entrepreneurs, businessmen, and other influential groups to provide advice on local development, while protecting their commercial rights to enhance the local economy. They were given investment and construction privileges through which they could “repay society” and “honour the family.”

In 2006, a media article reported that the “mobilisation meeting for building a new socialist countryside” was held in the county-level city of Hejin, Shanxi Province. The parking lot in front of the venue was filled with more than 500 luxury cars. These vehicles that symbolised wealth belonged to rich village officials in Hejin City. Ren Dianmin, a 37-year-old multimillionaire who served as the head of Renjiayao Village, was one of them. He said, “I have already done infrastructure construction like road hardening, without state investment, for the village, and the quality is higher than the official standard.”[4]

This media article reveals a trend of wealthy groups intervening in rural development. New gentry has indeed become a model for local management guided by elite groups, such as the wealthy, entrepreneurs, and highly educated officials and scholars. Their identity is symbolic (Cai et al. 2021: 56), as they are recognised by locals as high-wage professionals with higher political status and prestige. This aligns with the emergence of an upper-middle class, which is likely to spend revenue on creative products and services, seeking alternative country life in rural areas.[5] The emergence of the upper-middle class provides the prerequisites for extensive rural gentrification. The driving factors include amenity migration (Tan and Zhou 2022), increased average rent through tourism (Cai et al. 2021; Wang and Su 2021), and deliberate intervention by the authorities for commodification profits (Zhang and Wang 2017). This process is widely associated with nostalgia and idealism (Nelson and Hines 2018) and reconstruction of the identity system of the rural community (Rao 2020). It is also closely integrated with the official cultural revival strategy through the rural revitalisation policy.[6]

Moreover, although selected traditional concepts and measures have been borrowed, the new gentry notion – based on the contemporary economy and social administrative system – is significantly different from the old circumstances based on the small-scale farming economy hundreds of years ago. President Xi Jinping affirmed rural revitalisation by elites when he inspected Guangdong Province in 2018 and pointed out that:

Rural revitalisation also requires a vigorous, fresh force. We must let the elites come to the rural stage and do what they can, and let farmers and entrepreneurs grow and develop in the countryside. Both urbanisation and counter-urbanisation should develop synchronously.[7]

Revival of traditional culture in the authorised harmony heritage discourse

In the context of the transformation of contemporary Chinese society, comprehending the use of Chinese heritage without understanding the relevant ideology is impossible (Madsen 2014). Retrieving moral and cultural ideals from Confucianism to revive the countryside and alleviate rural-urban tensions began as early as the 1930s, as attempted in an experiment by Liang Shuming 梁漱溟 (Wu and Tong 2009). In the 1980s, cultural revival was evident in movements such as the New Confucianism (Makeham 2003; Oldstone-Moore 2003). Since the 1990s, the state has promoted Confucianism in education, which has become the core spiritual content of contemporary Chinese culture, as demonstrated by Confucius Institutes around the world or in the 2010 Shanghai World Expo (Hubbert 2016). “Useful values” were extracted from a rich database of Chinese Confucianism and applied to contemporary contexts (Hwang 2006, 2012). Meanwhile, the rapid development in contemporary China has not only caused growing inequalities, uncertainties, and anxiety, but has also raised concern about socioeconomic and cultural changes, stimulating interest of urban elites in social construction. This concern is ambiguous, filled with nostalgia for cultural traditions and the vision of an idealised, high-quality, modern, rural livelihood. Thus, an alternative cultural ideology that is acceptable to all ethnic groups and strata in China has been seen as needed to offset the ideological vacuum after the reform and opening up policy and to counter the “peaceful evolution” theory of the United States (Saussy 2001; Ong 2013). Traditional cultural values and entities that were condemned have therefore been rediscovered and defined, with “new vocabulary and ways to conceptualise the past” (Svensson and Maags 2018: 14) mobilised to reinterpret cultural heritage. Therefore, cultural heritage provides a means of communicating official discourse and cultural intentions (Denton 2005, 2014; Zhang R. 2017), enhances national pride, and inspires a reexamination of the history of China, its culture and its traditions, which were deemed to be an effective approach to alleviating social contradictions. With the “revival of traditional culture” becoming China’s national strategy,[8] the exploration and promotion of traditional culture became important tasks for local governments and cultural publicity departments, revealing the interrelated and interchangeable traits between history and heritage (Park 2013: 15; Fiskesjö 2019). Heritage reutilisation is seen as an effective method for fostering collective identity (Zhu and Maags 2020), enhancing rural development, and coordinating the balance between urban, rural, and authoritarian official power (Oakes 2013).

Yan (2015), coining the term “Chinese harmony discourse,” emphasises the official harmonious role of the conservation and use of heritage in social construction and politics. Under the guidance and support of this authorised heritage discourse (Smith 2006), the new gentry consider themselves capable of (and obliged to) exercising their rights in rural areas as “citizens of modern democratic society” and moralists of conserving traditional cultural heritage and essence, thus taking the lead as regional leaders in the construction of local society and group “consensus.”

Xixinan Village: A case study

Implementation of the new gentry notion in Xixinan

The new gentry group intervention was initiated around 2010. In 2009, Huangshan City, where Xixinan Village is located, implemented the “Hundred Villages and Thousand Buildings” (baicun qianzhuang 百村千幢) project. The plan was to invest RMB six billion in five years to promote the conservation and reutilisation of residential folk buildings in traditional villages.[9] The municipal government highlighted the preferential terms, providing permission and support for external private capital and individuals to legally acquire and reuse folk houses and collectively own buildings. In 2014, the World Bank approved a loan of USD 100 million for the “Huangshan New Countryside Construction Demonstration Project” to redevelop rural areas and conserve diverse cultural heritage sites.[10] In addition, a considerable portion of the cost would be used for the resettlement of native residents to create room for new functions and entrants. Consequently, many elite individuals and organisations from developed areas such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen came to Xixinan to buy or rent historical buildings, obtain usage rights to local land, and restore and reutilise historical assets.

In 2014, led by Kongjian Yu, a landscape scholar known for his ecological landscape design concept (Yu 2020), a subsidiary of Beijing Wangshan Investment Co., Ltd. (望山投資有限公司), the Turenscape, was established based on the reutilisation of historical buildings in Xixinan Village (see Figure 2). The company also conducted a series of international designer training projects and academic study activities with academic institutions. Moreover, in collaboration with the local government, new creative cultural industries and normalised academic and cultural exchange mechanisms were established. These measures and activities promoted the renovation of historical buildings and the investment of immigrants (Yu 2017). In 2020, the Huangshan Government once again claimed that Xixinan Village would be a model site in the Huangshan Municipal Investment Plan, which participated in the village’s international and elitist development.

Figure 2. Different views of the Turenscape (picture 2) and Wangshan Life workstation (picture 1), a major investment company in Xixinan, September 2021. This was based on historical warehouse reutilisation.

Credit: authors.

Xixinan Village has indeed undergone radical changes in its industrial and population composition. By 2021, more than 53 hostels and creative industrial centres had been constructed, of which 37 belonged to immigrant investors. There were 85 creative artists from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen and more than 20 cultural tourism marketing activities, including “Super cello,” “Squire music festival,” “Wangshan festival of ideal life,” and “Fengyang market.” Xixinan Village hence became a popular historical tourism destination in eastern China. By 2020, the village population had risen to 4,283 from 3,248 in 2005. The total private capital investment in 2018 was RMB 160 million, drastically rising to RMB 250 million in 2023.[11] The rising population mainly comprises immigrants. They have relatively high incomes, are well-educated, and had mostly engaged in the service industry and businesses before migrating to Xixinan Village.

These changes were typically “official-oriented” and continuously intensified privatisation, with the encouragement and guidance of the local government. In terms of performance, private capital mainly focuses on the service sector, establishing hotels, luxury restaurants, bars, and organic farms. Consequently, an exclusive, luxurious environment attracts people with similar identities and income levels, strengthening the formation of the regional new gentry and promoting Xixinan Village as an ideal paradise and a nostalgic haven (see Figure 3) for the petty bourgeoisie to escape the urban world rather than a communal rural area. Nevertheless, as we will explain later on, this paradise does not serve the interests of the original residents, who are farmers or craftsmen.

Figure 3. The picture figures a replicated memorial archway within the village, representing the nostalgia of a cultured gentry.

Credit: authors.

The process of rural revitalisation and heritage conservation – including the involvement of the new gentry – provided the investments and jobs urgently needed by local governments. Their needs and vision for the local communities also coincided with those of the central administration. Cultural heritage affairs are usually designated by official authorities. However, the sluggish designation process in the countryside allowed the new gentry to empower themselves: based on Chinese harmony discourse, district officials and media indeed held up the new gentry as examples in rural revitalisation, enabling them to play a more important role in the conservation of heritage assets, management, and operation of local affairs. Despite controversy, the traditional notion of “gentry” has been gradually revived by capitalising on the deficiencies in government functions. Confucianism is appropriated by the new gentry to develop a heritage discourse that legitimises these activities and gains the acquiescence of local residents.

Rooted in the countryside: The responsibility of creating a harmonious society

The shaping of the new gentry notion is consistent with the call to construct a harmonious society and with the policy of cultural heritage conservation. As described in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Law (2011), the process should be “conducive to strengthening the cultural identity of the Chinese nation, maintaining national unity and solidarity, promoting social harmony, and fostering sustainable development.”[12] Since 2012, the value of traditional villages has been highlighted anew because:

The foundation of China’s traditional culture is in the countryside. Traditional villages retain a rich and colourful cultural heritage and are important carriers of traditional Chinese civilisation (…). The conservation of traditional villages is (...) the conservation of tangible and intangible heritage and traditional culture.[13]

Consequently, the core of authorised heritage discourse is ostensibly using heritage conservation in rural areas to achieve the rural and cultural revitalisation.

Therefore, for the new gentry, gaining the legitimacy to extract rural resources and occupy the land of historical assets is derived from their abilities and the necessity to promote social harmony and grassroots governance (see Figure 4). The charisma of individual political leaders and the strong tradition of “rule by ethic” play an important role in shaping heritage landscapes (Cui 2018: 224). B1, an owner of a local hotel, who proudly identifies as a member of the new gentry, stated:

Immigrants should establish rules and play a supervisory role; however, it is more important to do so in practice rather than just shouting slogans. We should popularise the knowledge of the legal system among villagers and cultivate an awareness of modern life. (Interview with participant B1, male, February 2022)

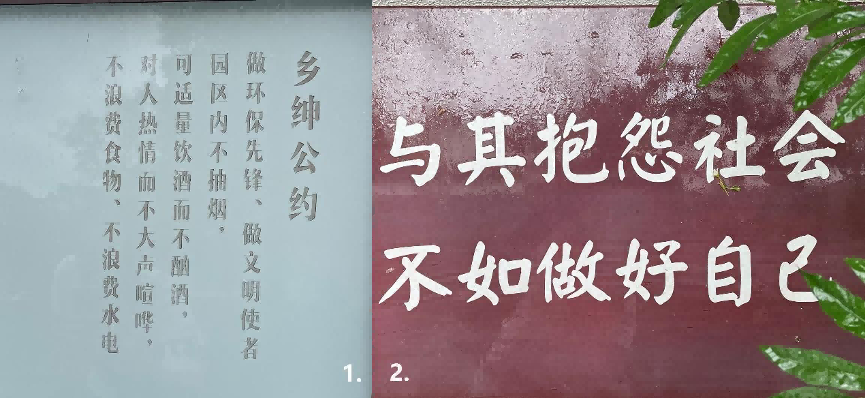

Figure 4. Pictures 1 and 2 are boards made by individuals from the new gentry, which aim to persuade villagers to be elegant, courteous, civilised, and to avoid complaining (September 2021).

Note: Picture 1 title: Gentry’s Pledge. Picture 2: Instead of complaining about society, it is better to improve yourself.

Credit: authors.

Due to sufficient capital and extensive personal relations, members of the new gentry such as the one quoted above have a strong voice and effective supervision capabilities at the local level:

In the case of illegal fishing or dumping garbage in the river, I would take photos and send them to cadres, who will immediately send people to investigate and manage it. We should create a better ecology for people and nature to live in harmony. (Interview with Participant B1, male, February 2022)

However, the contribution of the new gentry to local rural development and heritage conservation is contradictory. Different people have different attitudes, which reveal a differentiation based on subjective evaluations and standpoints. People living in Xixinan are mainly middle-aged and elderly people. When asked why young people did not stay to work, a local, A1, replied as follows:

There are few opportunities to earn money in the village. Investment in a hostel requires excessive funds, and I cannot compete with immigrants. Local jobs mainly involve housekeeping, which is unsustainable. Young people who want to earn money leave to look for work. (Interview with participant A1, female, February 2022)

A similar response was provided by another female local villager, A2. The greatest economic impact of the extensive intervention and investment by the elites is an increase in the price of homesteads in prime rural areas. This is speculation on the countryside’s most valuable assets (Perkins 2006) within the broader rural revitalisation movement under slogans such as “Rejuvenate idle rural assets” (panhuo xianzhi zichan 盤活閒置資產), which does not directly lead to productive investments and jobs. D1 is a rural asset agent. In a meeting he attended with bureaucrats from a neighbouring province, he said: “Major immigrants bought historic buildings and houses just for personal enjoyment.” The new gentry group has also been criticised for their approach in reusing historic buildings and the impact on the overall appearance of the village. Furthermore, D2, a local retired high school teacher, argued that exemplary representatives of the new gentry, such as B1, are still a minority, and that the immigrant community is a “mixed bag.” He emphasised that most members of the new gentry buy an asset and remodel it according to their preferences without considering the historic landscape. D3, a young local male cultural heritage activist, highlighted the dilemma of heritage conservation, where local authorities tend to neglect the preservation of authenticity and the overall appearance for short-term interests, such as asset selling:

We had a detailed conservation control plan for Xixinan with French heritage conservation experts years ago, but the conservation concept was empty talk, because local leaders would only consider whether they could make an immediate profit in five or six years or less. (Interview with participant D3, male, March 2022)

Furthermore, contrary to the new gentry’s self-claims and the views of some officials in series B, private voices such as D series, and male university scholars like C3 and C4, argued that the advantageous position and agglomeration effect of the new gentry had formed a self-closing identity group that had an oppressive effect on the villagers. Members of the new gentry believe they have a responsibility and obligation to educate locals; however, this paternalistic standpoint is underpinned by inequality. A retired local high school teacher, D2, complained that majority of the new gentry occupied the best plots and were reluctant to interact with locals:

Many investors lock the door through the year after buying a house, which is disappointing because you cannot visit as before. They come here when they are “happy” and go back (to the big city) if they do not want to stay. They do not have a sense of identity within the local culture or community. (Interview with participant D2, male, March 2022)

However, the new gentry has raised objections to this comment. A common perception is that local villagers lack gratitude and courtesy and are only concerned about benefits, making it difficult for migrant groups to effectively help local villagers. D3 responds to this as follows:

I think equality is essential when it comes to issues related to our own interests. Placing oneself in the right position is important, as this is a process of equivalent exchange rather than “noble people” (gaoguizhe 高貴者) helping “ordinary people” (putongren 普通人). (Interview with participant D3, male, March 2022)

Notably, local bureaucrats are willing to receive and cooperate with the demands of the new gentry and promote their functions as part of their political achievements. Investor/entrepreneur B1’s property is a complex, combining a hotel and an ecological farm, and employing local people. Thus, local officials describe his business as an exemplary model of regional development, showcasing it to guests and foreign government officials and seeking to replicate it. Although most of the new gentry come from big cities, they do not regard themselves as outlanders (waidiren 外地人). After settling, they often use interpersonal relationships to increase their investments. Consequently, over time, the new gentry has grown and shown increasing centripetal force: the upper-middle class continues to arrive in Xixinan Village to invest and spend, which has improved its reputation and economic level. In this process, Xixinan did not suffer from the obvious “free market solutions” of gentrification issues, leading local inhabitants to no longer being able to afford increasing land prices, goods, and services (Hwang and Lin 2016: 3). This is closely related to the Chinese land policy. Villagers have collective ownership of the land, so immigrants and investors can only negotiate with the villagers and “rent” the land for a limited time (generally 20 to 40 years), rather than gain ownership of the land. The government does not have the right to force villagers to sell their homesteads. However, with the continuous influx of immigrants and the return of original villagers who are attracted by investment, the limited land and high-quality historical building resources in Xixinan Village have gradually become scarce, causing a differential rent phenomenon (Economakis 2010; Loo et al. 2018).

Overall, the elite group-oriented development model in Xixinan undoubtedly has exploratory significance, but the tendency towards benefits and privileges for the new gentry remains controversial. Currently, district officials remain inclined to adopt this model.[14]

Discussion: Beyond the official narrative

Beyond the official narrative, examining the new gentry phenomenon in connection with historical village redevelopment should be done cautiously. Clearly, the new gentry is emerging as a critical driving force of gentrification in historical villages; however, members of this group have become spokesmen of privatisation interests and discourse brought to the fore. This process has some similarities with other rural gentrification studies. For instance, numerous research on gentrification and rural gentrification in China has critically pointed out that rent increases, improvements in community infrastructure, and disruptions in the development process do not necessarily undermine the interests of vulnerable groups (Benjamin 2005). Instead, locals and vulnerable groups tend to embrace the process and benefit from it depending on the degree of connection and participation between locals and elites in local development.

However, in the case of Xixinan, two questions arise: (1) As this process has increased profits and benefitted the majority, which group benefits more from the redistribution? (2) As locals and ordinary citizens may not directly oppose the development process and may even explore new economic opportunities, how long can the process sustain rapid profit growth? Essentially, the widening gap between urban and rural areas and stratification in China have been concealed by rapid economic growth for decades. However, once growth slows down, the discrepancy is magnified and notable consequences may emerge. The support received and benefits generated in the present are not sufficient to justify these discrepancies as reasonable in the long term.

The greatest contradiction that emerges from new gentry reinvention are the inequalities and group divisions associated with overall growth. Although returns on human capital have increased, social elites are still crucial in resource allocation. In Xixinan, investment in and premiumisation of the area have resulted in an improved community environment and overall living standards, as reflected in villagers’ higher expectations in terms of salary and working conditions. However, only a fraction of villagers enjoyed the benefits of development. For instance, some villagers are employed by new gentry as hostel managers and housekeepers, but such positions are limited. This process brings higher salaries and a sense of superiority to specific groups, but implicitly discriminates against other community members, exacerbating unfairness and inequity. Investor B1 complained that new hostel construction is not as profitable because the operating cost is higher, since the locals were seeking higher pay and privileges. Therefore, owners preferred to hire cheaper labourers from other areas, such as Qiankou Town in Huizhou District. Similarly, a local villager believed that the arrival of immigrants would promote the consumption and purchase of more local products; what he did not expect was that they would all shop online because the consumption needs of the new gentry are different from local output.

Similarly, the heritage-making process is also controversial. Multifaceted contradictions and dissonances are generated among different stakeholders due to lack of coherent actions and attitudes (Tunbridge and Ashworth 1997). The property rights of nonheritage historical buildings have been a grey area, as the transfer of collective property ownership is privately approved by village committees and villagers without the input of the central government due to a lack of legal basis. Ownership after property transfer is highly uncertain without legal guarantees or official recognition. Consequently, social and economic power prevail, thereby undermining the rights of vulnerable groups. In Xixinan, the most valuable, best preserved, and best-positioned public historical assets are occupied by the new gentry. By 2021, 21 of the 37 business assets run by immigrants were based on the renovation of historical buildings. Based on prominent influence, Wangshan Company has control of premium assets from land parcels to historical buildings (Chen and Kong 2021: 13), including a traditional Ming period house (laowuge 老屋閣) labelled as a major historical and cultural site protected at the national level (quanguo zhongdian wenwu baohu danwei 全國重點文物保護單位), and the remnants of a traditional Hui-style garden (guoyuan 果園). Participants D2 and D3 have criticised this control because the Turenscape firm utilises both public heritage sites as their profit proxy by using them for commercial activities and as customer attractions. Other historical buildings such as the Hetianli Hotel, which was transformed by the Xixinan commune, and Wangshangongshe, which used to be an old public primary school, are now commercially used by Wangshan Investment. Besides original historical assets, relocated historical buildings have also become very common in the village. For example, Wei Yanfu, a private investment project, owned 16 relocated historical buildings for leisure. Despite various heritage sites being revitalised under the reutilisation scheme, only private entities profited. The township government could share dividends through financial transfer payments from the higher-level district government according to Xixinan’s tax revenues. However, township bureaucrats were also concerned that the new gentry group controlled numerous resources, which may hinder official planning and profit distribution. Finally, native villagers rarely benefitted directly from the process, and the separation between residents and heritage sites became apparent, presenting a settlement concentration gap between native villagers and the new gentry. This difference in experience is also reflected in tourists’ feedback. Luxury establishments and properties owned by immigrants are inaccessible to most tourists. One university student visitor stated that these reutilised historical buildings are a deterrent because they look so expensive, she did not dare to visit or patronise them. Another local visitor was disappointed that they could not visit an old mansion that had been converted into a coffee bar, as it was open only to purchasing customers but not to visitors. Visitors can only access areas that are not occupied by the new gentry. The notion of new gentry is still politically sensitive and controversial – even with tacit support at the official level – because it gradually increases investment and the motivation for increased housing prices, thereby failing to promote local management and community construction. Conversely, the current local government is increasingly relying on the collectively-owned tourism company Langmanhong, established around 2020, to manage Xixinan’s development. Its intervention has led to an increasing number of tourists wanting to enjoy local food and buy souvenirs and local products. Economic opportunities for local villagers have increased, such as stores, restaurants, and street vendors, but these opportunities mainly come from tourists rather than from the new gentry. Therefore, even though closely tied to the revival of traditional culture and the reutilisation of heritage, whether the new gentry model can promote local democracy and enhance community autonomy is still questionable. Due to limited funds, sites and buildings with a low added value will inevitably lack attention and rely on the assistance of private elites, risking the separation of history from the local community (Hodges and Watson 2000: 232).

Conclusion

This research was conducted in the context of the current macro-ideological and cultural transformation in China. The reinterpretation and use of heritage discourse are currently associated with the privatisation and intervention of elite groups who dominate the process. Thus, the new gentry can select nostalgic memories and aspects of traditional cultural revitalisation to match the demands of contemporary social transformation and diversified aesthetic expressions. Behind these appearances is the seizure and division of rural land and resources by private capital and elites. This magnifies individual achievements and economic growth, while ignoring micro-cultural and sustainable social ecology at the local level. However, the harmonious official narrative in Xixinan presents the role of the new gentry group in social management and local investment as consistent with the traditional gentry groups centuries ago. A vision of a “top-down” oriented harmonious society is constructed. In this process, the role of the new gentry group is to compensate for the weaknesses in administrative capacity and funding at the local government level. Additionally, they form an intermediary and buffer zone between official and folk discourses. This creates an inseparable link between the new gentry concept, revival of traditional culture, heritage reuse, and “empowerment” of official Chinese ideology. The issue of class division and the unpleasant history of the countryside have been deliberately erased, but replaced by a vision of a prosperous, communal, and harmonious society led by the well-educated new gentry group.

The restoration, transformation, and reutilisation of heritage sites play a decisive role in the rural revitalisation, and heritage discourse becomes a tool to legitimise the elite’s role in this process. The dozens of luxury hostels, real estate projects, and the international conference centre in Xixinan Village highlight the unilateral process of “institutionalisation of symbols of elite cultural experiences as the epitome of ‘heritage’” (Waterton and Smith 2010: 11). This overshadows authentic grassroots discourse and inevitably leads towards gentrification in historical regions. However, it is still widely embraced by official discourse and adopted in the revitalisation of Chinese traditional villages and historical regions. The subjects of local power and official discourse form a close-knit, self-perpetuating bond, thereby coercing other groups into a predesigned development path without the opportunity to present counter-voices and possibilities. This transformation is unfolding at an alarming rate in historical villages in China without solid research, monitoring, and evaluation. Thus, further concerns should be raised in the relevant forums.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the residents and participants in Xixinan for their help in the research, their availability for interviews, and generous arrangement of site visits; as well as to Mr Wu Junhang (吳軍航), Mr Du Chunping (杜春平) and Mr Zhang Junxi (張俊西) for research material support. Our gratitude too to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments.

This work was supported by the National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences (Beijing, China), Grant number 21ZD01, and the Humanities and Social Science Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China. It has also been funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany in the framework of URBANI[XX] (project number: 01DO17037).

Manuscript received on 2 February 2022. Accepted on 21 September 2023.

References

ALONSO GONZÁLEZ, Pablo. 2017. “Heritage and Rural Gentrification in Spain: The Case of Santiago Millas.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23(2): 125-40.

BENJAMIN, Solomon. 2005. Productive Slums: The Centrality of Urban Land in Shaping Employment and City Politics. Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

BESSIÈRE, Jacinthe. 1998. “Local Development and Heritage: Traditional Food and Cuisine as Tourist Attractions in Rural Areas.” Sociologia Ruralis 38(1): 21-34.

CAI, Xiaomei 蔡曉梅, LIU Meixin 劉美新, LIN Jiahui 林家惠, and MA Guoqing 麻國慶. 2021. “旅遊發展背景下鄉村紳士化的動態表徵與形成機制: 以廣東惠州上良村為例” (Lüyou fazhan beijing xia xiangcun shenshihua de dongtai biaozhi yu xingcheng jizhi: Yi Guangdong Huizhou Shanglang cun wei li, Dynamic representation and formation mechanism of rural gentrification in the context of tourism development: A case study of Shangliang Village, Huizhou, Guangdong). Lüyou xuekan (旅遊學刊) 36(5): 55-68.

CAO, Zhenghan 曹正漢, and ZHANG Xiaoming 張曉鳴. 2017. “郡縣制國家的社會治理邏輯: 清代基層社會的‘控制與自治相結合模式’研究” (Junxian zhi guojia de shehui zhili luoji: Qingdai jiceng shehui de “kongzhi yu zizhi xiang jiehe moshi” yanjiu, The logic of social governance in a prefectures-and-counties state: On the origins of “dual-track system of regulation and autonomy” in Qing dynasty.” Xueshujie (學術界) 10: 216-27, 326-7.

CHEN, Peipei, Min ZHANG, and Ying WANG. 2024. “Beyond Displacement: The Co-existence of Newcomers and Local Residents in the Process of Rural Tourism Gentrification in China.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 32(1): 8-26.

CHEN, Pinyu, and Xiang KONG. 2021. “Tourism-led Commodification of Place and Rural Transformation Development: A Case Study of Xixinan Village, Huangshan, China.” Land 10(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070694

COOKE, Susette. 2018. “Telling Stories in a Borderland: The Evolving Life of Ma Bufang’s Official Residence.” In Christina MAAGS, and Marina SVENSSON (eds.), Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. 41-66.

CUI, Jinze. 2018. “Heritage Visions of Mayor Geng Yanbo: Re-creating the City of Datong.” In Christina MAAGS, and Marina SVENSSON (eds.), Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. 223-44.

DAVIS, Deborah S. 2000. “Social Class Transformation in Urban China: Training, Hiring, and Promoting Urban Professionals and Managers after 1949.” Modern China 26(3): 251-75.

DENTON, Kirk A. 2005. “Museums, Memorial Sites and Exhibitionary Culture in the People’s Republic of China.” The China Quarterly 183: 565-86.

——. 2014. “Introduction.” In Kirk A. DENTON, Exhibiting the Past: Historical Memory and the Politics of Museums in Postsocialist China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. 1-26.

ECONOMAKIS, George. 2010. “Differential Rent, Market Values And ‘False’ Social Value: Some Implications.” Critique 38(2): 253-66.

ESHERICK, Joseph, and Mary BACKUS RANKIN (eds.). 1990. Chinese Local Elites and Patterns of Dominance. Berkeley: University of California Press.

FAIRBANK, John. K., and Roderick MACFARQUHAR (eds.). 1987. The Cambridge History of China: The People's Republic. Volume 14 Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

FEI, Xiaotong. 1953. China’s Gentry: Essays on Rural-urban Relations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 1992. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

FISKESJÖ, Magnus. 2019. “Review of the book World Heritage Craze in China: Universal Discourse, National Culture, and Local Memory, by Haiming Yan.” Asian Perspectives 58(2): 401-4.

GHERTNER, D. Asher. 2015. “Why Gentrification Theory Fails in ‘Much of the World.’” City 19(4): 552-63.

GU, Chaolin, and Jianfa SHEN. 2003. “Transformation of Urban Socio-spatial Structure in Socialist Market Economies: The Case of Beijing.” Habitat International 27(1): 107-22.

HERZFELD, Michael. 2016. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics and the Real Life of States, Societies, and Institutions (3rd ed.). London: Routledge.

HODGES, Andrew, and Steve WATSON. 2000. “Community-based Heritage Management: A Case Study and Agenda for Research.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 6(3): 231-43.

HUBBERT, Jennifer. 2016. “Back to the Future: The Politics of Culture at the Shanghai Expo.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 20(1): 48-64.

HWANG, Jackelyn, and Jeffrey LIN. 2016. “What Have We Learned About the Causes of Recent Gentrification?” Cityscape 18(3): 9-26.

HWANG, Kwang-Kuo. 2006. “Constructive Realism and Confucian Relationalism.” In Uichol KIM, Kuo-Shu YANG, and Kwang-Kuo HWANG (eds.), Indigenous and Cultural Psychology: Understanding People in Context. Cham: Springer. 73-107.

——. 2012. Foundations of Chinese Psychology: Confucian Social Relations (vol. 1). Cham: Springer.

JAIN-CHANDRA, Sonali, Niny KHOR, Rui MANO, Johanna SCHAUER, Philippe WINGENDER, and Juzhong ZHUANG. 2018. “Inequality in China: Trends, Drivers and Policy Remedies.” IMF Working Papers 127. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/06/05/Inequality-in-China-Trends-Drivers-and-Policy-Remedies-45878 (accessed on 25 April 2024).

LEY, David. 1994. “Gentrification and the Politics of the New Middle Class.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 12(1): 53-74.

LEY, David, and Sin Yih TEO. 2014. “Gentrification in Hong Kong? Epistemology vs. Ontology.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38(4): 1286-303.

——. 2020. “Is Comparative Gentrification Possible? Sceptical Voices from Hong Kong.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44(1): 166-72.

LI, Chunling, and Yiming FAN, 2020. “Housing Wealth Inequality in Urban China: The Transition from Welfare Allocation to Market Differentiation.” The Journal of Chinese Sociology 7: 1-17.

LOO, Becky P., John R. BRYSON, Meng SONG, and Catherine HARRIS. 2018. “Risking Multi-billion Decisions on Underground Railways: Land Value Capture, Differential Rent and Financialization in London and Hong Kong.” Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 81: 403-12.

LU, Lin 陸林, CHEN Huifeng 陳慧峰, and FU Linrong 符琳蓉. 2022. “旅遊開發背景下傳統村落功能演變的過程與機制: 以黃山市西溪南村為例” (Lüyou kaifa beijing xia chuantong cunluo gongneng yanbian de guocheng yu jizhi: Yi Huangshan shi Xixinan cun wei li, Process and mechanism of function evolution of traditional villages under the background of tourism development: A case study of Xixinan Village, Huangshan City). Dili kexue (地理科學) 42(5): 874-84.

MADSEN, Richard. 2014. “From Socialist Ideology to Cultural Heritage: The Changing Basis of Legitimacy in the People’s Republic of China.” Anthropology & Medicine 21(1): 58-70.

MAKEHAM, John. 2003. “The Retrospective Creation of New Confucianism.” In John MAKEHAM (ed.), New Confucianism: A Critical Examination. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 25-53.

McDERMOTT, Joseph P. 2013. The Making of a New Rural Order in South China: Volume 1, Village, Land, and Lineage in Huizhou, 900-1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MILLER, Harry. 2008. State versus Gentry in Late Ming Dynasty China, 1572-1644. Cham: Springer.

NELSON, Lise, and Peter B. NELSON. 2011. “The Global Rural: Gentrification and Linked Migration in the Rural USA.” Progress in Human Geography 35(4): 441-59.

NELSON, Peter B., and J. Dwight HINES. 2018. “Rural Gentrification and Networks of Capital Accumulation: A Case Study of Jackson, Wyoming.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50(7): 1473-95.

OAKES, Tim. 2013. “Heritage as Improvement: Cultural Display and Contested Governance in Rural China.” Modern China 39(4): 380-407.

OLDSTONE-MOORE, Jennifer. 2003. “Book Review of Reinventing Confucianism/Xian dai xin rujia: The New Confucian Movement by Umberto Bresciani.” The Journal of Asian Studies 62(2): 574-6.

ONG, Russell. 2013. China’s Security Interests in the Post-Cold War Era. London: Routledge.

PARK, Hyung Yu. 2013. Heritage Tourism. London: Routledge.

PERKINS, Harvey C. 2006. “Commodification: Re-resourcing Rural Areas.” In Paul CLOKE, Terry MARSDEN, and Patrick MOONEY (eds.), Handbook of Rural Studies. 243-57.

RAO, Xiaofang 饒小芳. 2020. 傳統村落的鄉村紳士化過程及影響因素研究: 以黃山市徽州區西溪南村為例 (Chuantong cunluo de xiangcun shenshihua guocheng ji yingxiang yinsu yanjiu: yi Huangshan shi Huizhou qu Xixinan cun weili, Study on rural gentrification process and influencing factors of traditional villages: A case study of Xixinan Village, Huizhou District, Huangshan City.” Master’s Thesis. Shanghai: Shanghai Normal University.

SAUSSY, Haun. 2001. Great Walls of Discourse and Other Adventures in Cultural China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center.

SHUE, Vivienne. 1980. Peasant China in Transition: The Dynamics of Development Towards Socialism, 1949-1956. Berkeley: University of California Press.

SMITH, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

SVENSSON, Marina, and Christina MAAGS. 2018. “Mapping the Chinese Heritage Regime.” In Christina MAAGS, and Marina SVENSSON (eds.), Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. 11-38.

TAN, Huayun, and Guohua ZHOU. 2022. “Gentrifying Rural Community Development: A Case Study of Bama Panyang River Basin in Guangxi, China.” Journal of Geographical Sciences 32: 1321-42.

THØGERSEN, Stig. 2009. “Revisiting a Dramatic Triangle: The State, Villagers, and Social Activists in Chinese Rural Reconstruction Projects.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 38(4): 9-33.

TUNBRIDGE, John E., and Gregory J. ASHWORTH. 1997. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict. London: Belhaven Press.

WANG, Hua 王華, and SU Weifeng 蘇偉鋒. 2021. “旅遊驅動型鄉村紳士化過程與機制研究: 以丹霞山兩村為例” (Lüyou qudong xing xiangcun shenshihua guocheng yu jizhi yanjiu: Yi Danxiashan liang cun wei li, Tourism-driven rural gentrification: Cases study of two villages in Danxia Mount). Lüyou xuekan (旅遊學刊) 36(5): 69-80.

WATERTON, Emma, and Laurajane SMITH. 2010. “The Recognition and Misrecognition of Community Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16(1-2): 4-15.

WATERTON, Emma, and Steve WATSON. 2013. “Framing Theory: Towards a Critical Imagination in Heritage Studies.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19(6): 546-61.

WATSON, James L. 1982. “Chinese Kinship Reconsidered: Anthropological Perspectives on Historical Research.” The China Quarterly 92: 589-622.

WITTFOGEL, Karl A. 1955. “Book Review of The Chinese Gentry: Studies on their Role in Nineteenth-Century Chinese Society by Chung-li Chang.” The American Historical Review 61(2): 404-5.

WU, Shugang, and Binchang TONG. 2009. “Liang Shuming’s Rural Reconstruction Experiment and Its Relevance for Building the New Socialist Countryside.” Contemporary Chinese Thought 40(3): 39-51.

XIAO, Ziyang 蕭子揚, and MA Enze 馬恩澤. 2018. “鄉村振興戰略背景下的新鄉賢研究: 一項文獻綜述” (Xiangcun zhenxing zhanlüe beijing xia de xin xiangxian yanjiu: Yi xiang wenxian zongshu, Research on new rural talents in the context of rural “revitalisation” strategy: A literature review). Shijie nongye (世界农业) 12: 76-80, 85.

YAN, Haiming. 2015. “World Heritage as Discourse: Knowledge, Discipline and Dissonance in Fujian Tulou Sites.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21(1): 65-80.

YANG, Guoqiang. 2018. “The Gentry, the Power of the Gentry and State Power in the Late Qing Dynasty.” In Ruiquan GAO, and Guanjun WU (eds.), Chinese History and Literature: New Ways to Examine China’s Past. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing. 55-77.

YU, Kongjian 俞孔堅. 2017. “‘新上山下鄉運動’與遺產村落保護及復興: 徽州西溪南村實踐” (“Xin shangshan xiaxiang yundong” yu yichan cunluo baohu ji fuxing: Huizhou Xixinan cun shijian, New Ruralism Movement in China and its impacts on protection and revitalisation of heritage villages: Xixinan experiment in Huizhou District, Anhui Province.” Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences (中國科學院院刊) 32(7): 696-710.

——. 2020. “Kongjian Yu: Turenscape Landscape Architecture, Urban Design, Architecture, Beijing.” Harvard Design Magazine 33. https://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/articles/kongjian-yu-turenscape-landscape-architecture-urban-design-architecture-beijing/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

ZHANG, Juan 張娟, and WANG Maojun 王茂軍. 2017. “鄉村紳士化進程中旅遊型村落生活空間重塑特徵研究: 以北京爨底下村為例” (Xiangcun shenshihua jincheng zhong lüyou xing cunluo shenghuo kongjian chongsu tezheng yanjiu: Yi Beijing Cuandixia cun wei li, The characteristics of the life space remodeling of tourism village during rural gentrification: The case of Cuandixia in Beijing). Renwen dili (人文地理) 32(2): 137-44.

ZHANG, Qian Forrest. 2015. “Class Differentiation in Rural China: Dynamics of Accumulation, Commodification and State Intervention.” Journal of Agrarian Change 15(3): 338-65.

ZHANG, Qingli 張清俐, and ZHANG Jie 張傑. 2014. “發掘鄉賢文化的時代價值” (Fajue xiangxian wenhua de shidai jiazhi, Discover the contemporary value of rural virtuous culture). Dangzheng ganbu cankao (党政干部参考) 22: 1.

ZHANG, Qingyuan, Lin LU, Jianfeng HUANG, and Xiao ZHANG. 2022. “Uneven Development and Tourism Gentrification in the Metropolitan Fringe: A Case Study of Wuzhen Xizha in Zhejiang Province, China.” Cities 121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103476

ZHANG, Rouran. 2017. “World Heritage Listing and Changes of Political Values: A Case Study in West Lake Cultural Landscape in Hangzhou, China.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23(3): 215-33.

ZHANG, Zhongli. 1955. The Chinese Gentry: Studies on their Role in Nineteenth-century Chinese Society. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

ZHAO, Yawei. 2019. “When Guesthouse Meets Home: The Time-space of Rural Gentrification in Southwest China.” Geoforum 100: 60-7.

ZHU, Yujie, and Plácido GONZÁLEZ MARTÍNEZ. 2022. “Heritage, Values and Gentrification: The Redevelopment of Historic Areas in China.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 28(4): 476-94.

ZHU, Yujie, and Christina MAAGS. 2020. Heritage Politics in China: The Power of the Past. London: Routledge.

[1] UNESCO, “Policy for the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into the Processes of the World Heritage Convention,” https://whc.unesco.org/en/compendium/55 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

[2] Yin Jie 尹婕, “新鄉賢(詞說兩會),” (Xin xiangxian (cishuo lianghui), New gentry (words from the two sessions)), People.cn (人民網), 16 March 2016, http://lianghui.people.com.cn/2016npc/BIG5/n1/2016/0316/c402194-28201941.html (accessed on 22 May 2024); “新鄉賢是鄉村振興重要力量” (Xin xiangxian shi xiangcun zhenxing zhongyao liliang, New gentry is an important force in rural revitalisation), Xinhua.com (新華網), 23 November 2021, www.news.cn/comments/2021-11/23/c_1128089817.htm (accessed on 16 February 2023).

[3]Jim Yardley, “In a Tidal Wave, China’s Masses Pour from Farm to City,” The New York Times, 12 September 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/12/weekinreview/in-a-tidal-wave-chinas-masses-pour-from-farm-to-city.html (accessed on 14 August 2022).

[4] Jiang Mingzhuo 蔣明倬, “富豪村官的新鄉紳治理” (Fuhao cunguan de xin xiangshen zhili, The new gentry governance of wealthy village officials), 21 shiji jingji baodao (21世紀經濟報導), 21 March 2006, https://finance.sina.cn/sa/2006-03-21/detail-ikknscsi3191005.d.html (accessed on 26 April 2024).

[5] Dominic Barton, “The Rise of the Middle Class in China and Its Impact on the Chinese and World Economies,” In US-China Economic Relations in the Next 10 Years: Towards Deeper Engagement and Mutual Benefit, 2013, https://www.chinausfocus.com/2022/wp-content/uploads/Part+02-Chapter+07.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2024).

[6] The rural revitalisation strategy (xiangcun zhenxing zhanlüe 鄉村振興戰略) was introduced in October 2017 and then applied in 2018. China now has increasing concern for the development of rural areas. In February 2021, the National Rural Revitalisation Administration (Guojia xiangcun zhenxing ju 國家鄉村振興局) was formed. In April 2021, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Promotion of Revitalisation of Rural Areas (Zhonghua renmin gongheguo xiangcun zhenxing cujin fa 中華人民共和國鄉村振興促進法) was adopted at the 28th session of the Standing Committee of the Thirteenth National People’s Congress, https://leap.unep.org/countries/cn/national-legislation/law-peoples-republic-china-promotion-revitalization-rural-areas (accessed on 26 April 2024).

[7] “通稿之外, 習近平提‘逆城鎮化’深意何在?” (Tonggao zhiwai, Xi Jinping ti “nicheng zhenhua” shenyi hezai?, Beyond the announcement, what is the deeper meaning of Xi Jinping’s reference to “counter-urbanisation”?), CCTV.com (央視網), 8 March 2018, http://m.news.cctv.com/2018/03/08/ARTIBwxcnyB124XWInPskZIC180308.shtml (accessed on 13 August 2022).

[8] General Office of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, General Office of the State Council 中共中央辦公廳, 國務院辦公廳, “關於實施中華優秀傳統文化傳承發展工程的意見” (Guanyu shishi Zhonghua youxiu chuantong wenhua chuancheng fazhan gongcheng de yijian, Opinions on the Implementation of the Project of Inheritance and Development of Chinese Traditional Culture Essence), 2017, www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2017/content_5171322.htm (accessed on 16 February 2023).

[9] World Bank 世行, “世行貸款安徽黃山新農村建設示範項目環境影響報告書” (Shihang daikuan Anhui Huangshan xin nongcun jianshe shifan xiangmu huanjing yingxiang baogaoshu, Environmental Impact Report of the World Bank-financed Anhui Huangshan New Rural Construction Demonstration Project), June 2013, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/ar/247301468218388638/pdf/E42280v10CHINE00Box377376B00PUBLIC0.pdf, p. 12 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

[10] The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China 中華人民共和國中央人民政府, “安徽黃山新農村建設等4個世行貸款項目獲得批准” (Anhui Huangshan xin nongcun jianshe deng 4 ge shihang daikuan xiangmu huode pizhun, Anhui Huangshan new rural construction and other four World Bank loan projects have been approved), 8 January 2014, www.gov.cn/gzdt/2014-01/08/content_2561934.htm (accessed on 14 August 2022).

[11] “西溪南: 目及之處皆風景” (Xixinan: Muji zhi chu jie fengjing, Xixinan: Scenery everywhere you look), Huangshan Daily (黃山日報), 15 March 2023, https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20230315A08AIY00 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

[12] The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China 中華人民共和國中央人民政府, “中華人民共和國非物質文化遺產法” (Zhonghua renmin gongheguo feiwuzhi wenhua yichan fa, Intangible Cultural Heritage Law of the People’s Republic of China), 25 February 2011, http://www.gov.cn/flfg/2011-02/25/content_1857449.htm (accessed on 14 August 2022).

[13] The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China 中華人民共和國中央人民政府, “住房城鄉建設部, 文化部, 國家文物局, 財政部關於開展傳統村落調查的通知” (Zhufang chengxiang jianshe bu, wenhua bu, guojia wenwu ju, caizheng bu guanyu kaizhan chuantong cunluo diaocha de tongzhi, Notice by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-rural Development, the Ministry of Culture, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, the Ministry of Finance regarding the implementation of the traditional village survey), 2012, http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2012-04/24/content_2121340.htm (accessed on 14 August 2022).

[14] Development and Reform Commission of Anhui Province 安徽省發展和改革委員會, “西溪南創意小鎮: ‘新鄉賢’推動鄉村復興的典範” (Xixinan chuangyi xiaozhen: “Xin xiangxian” tuidong xiangcun fuxing de dianfan, Xixinan creative town: “New gentry” as a model for promoting rural revival), 2021, https://fzggw.ah.gov.cn/jgsz/jgcs/fzzlhghcsgmjjdybgs/ghjzc/146296841.html (accessed on 13 August 2022).