BOOK REVIEWS

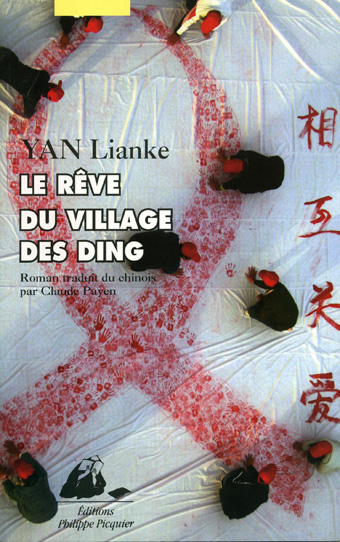

Yan Lianke, Le Rêve du Village des Ding

The HIV/AIDS epidemic that spread in Henan Province (and beyond) in the 1990s through unsafe blood collection represented – in many ways – a watershed for Chinese society in its interaction with the state. While official attitudes did not change perceptibly before the SARS outbreak of 2003, and remained reticent even after that (no senior official in Henan has been held to account; two of the provincial secretaries concerned, Li Changchun and Li Keqiang, hold Politburo standing committee positions today (1)), the perceived legitimacy of non-governmental organisations was greatly enhanced. Similarly, in a post-Tiananmen context in which writers and intellectuals were reluctant to embrace political agendas in the public arena, the type of social activism that grew out of the AIDS crisis offered a model of how to go about “changing mindsets” in a bottom-up manner, rather than offering the theoretical blueprints for democratisation for which the 1989 activists were so strongly criticised. Gao Yaojie played a central role in raising awareness among China’s independent intellectuals and journalists, in particular Ai Xiaoming, who has made several documentaries about AIDS: The Epic of Central Plains (Zhongyuan ji shi, 2006) deals specifically with Henan; her more recent film, made together with Hu Jie, Care and Love (Guan ai zhi jia, 2007) is dedicated to a village near Xingtai (Southern Hebei), where a woman who has been infected with HIV in a hospital sues the authorities for compensation. This social interest in the “underprivileged” (ruoshi qunti or weak groups), and its unrebuttable political legitimacy in holding the state to account, generated a new style of intellectual and social engagement.

Yan Lianke, the first fiction writer to become interested in the subject, also read Gao Yaojie’s early accounts of the situation in Henan in the mid- 1990s, and as a native of the province himself, he decided to pursue research on the matter. As he stated in an interview published in Southern Weekend in 2006, when Gao Yaojie explained in detail how “blood heads” would go around the fields to collect blood, using slightly bigger pouches to trick the peasants and making them lie down so as to feel less dizzy, “I felt that I had to write something.”(2)

Reportage literature (baogao wenxue) is a strong tradition in modern Chinese writing, with roots both in May Fourth (Mao Dun) and in the 1980s (Liu Binyan(3) and Dai Qing), but it seems that Yan Lianke was determined to use the fictional genre from the very beginning, forming the project of writing both a novel and a “document” in which he would record all the “unheard, unimaginable, and shocking matters” that are too terrifying to be used directly in fiction (he still plans to do so).(4) In another interview he refers to Ba Jin’s injunction that literature must “tell the truth” (jiang zhen hua). The French translation discussed in the present review, first published in 2007 and recently released in paperback, remains the only translation to date, and is therefore important in bringing Yan’s work to a wider audience, despite some shortcomings discussed below.

Yan, born in 1958 in Song County (near Luoyang), was originally a writer in the propaganda department of the People’s Liberation Army (like Mo Yan). He began writing satirical fiction in the 1990s, attracting attention with The Summer Sun Sets (Xia ri luo, 1994), which depicts career jostling within the PLA (a young army cook commits suicide, ruining his superiors’ prospects of advancement). The Joy of Living (Shou huo, 2004) portrays local officials bent on making money out of anything, even the remnants of Communism: a local cadre organises a group of disabled people into a travelling circus in order to make enough money to buy Lenin’s corpse.(5) After this publication, Yan was asked to resign from the PLA and became an employee of the Writers’ Association, which remains his “work unit” today. Serve the People (Wei renmin fuwu, 2005(6) ) attracted much attention in the West following the recall of the issue of the Guangzhou literary journal Huacheng in which it was originally published. Its depiction of a whole army camp thrown into havoc by the adventures of a division commander’s wife (who seduces his orderly), though sexually scandalous on the surface, is perhaps most noteworthy for its depiction of the impunity enjoyed by high-ranking officers during the Cultural Revolution: the commander volunteers to dissolve his entire division under a pilot scheme simply to rid himself of his wife’s many lovers.(7)

It was in the aftermath of these two works that Yan turned to seriously researching the AIDS crisis in Henan. He accompanied a Chinese- American medical researcher to a village near Kaifeng on a total of seven visits over three years, until Dingzhuang meng was published in 2006 by Shanghai wenyi chubanshe. Controversy followed: the authorisation of distribution was withdrawn by the General Administration on Press and Publications (supervised by the Central Propaganda Department, by this time under the leadership of Li Changchun), and reprints were forbidden. However, copies already in bookshops continued to be sold, and pirated versions circulated widely. Yan had originally intended the royalties to be paid to the village in which he had carried out his research, and consequently sued the publisher when, following the restrictions, the latter refused to pay the promised amount. A settlement was finally reached under which the publisher paid the author, who donated the money to the village.(8)

Yan highlights that his use of fiction is a way of toning down a reality that is in some ways inconceivably frightening. He has deliberately left out stories reported to him about collecting blood in plastic soy sauce or vinegar bags, and washing out the used bags in a pool that eventually turned red. He also chose to leave aside his first fictional idea of an imaginary country linked to the rest of the world by a blood pipeline through which local officials export blood to achieve the country’s rise to the rank of world power. These cuts should not be seen as mere self-censorship (at least not as purely political self-censorship), but also to reflect a preoccupation with finding an adequate form for what remains an untellable reality, a form that is both helpful to understanding the objective situation and true to the subjective experience of the villagers themselves. Here lies the originality of the book, which despite fantastic elements and overtones, never resorts to the sensationalism that characterises some of China’s contemporary fiction, most notably Yu Hua’s recent novel Brothers (Xiongdi).(9)

The story is narrated in the first person by a dead child, Ding Qiang, who died of eating a poisoned tomato given him by the villagers because his father is the “blood king” of Ding village. The story, though harrowing, is simple enough. Ten years before the time when the narration begins, after initially resisting a scheme formulated by provincial officials to attain development through selling blood, the Ding villagers are persuaded by a gesture made by the narrator’s grandfather, the respected elder Ding Shuiyang, who, scooping water from a muddy source by the river, proclaims: “It can’t be scooped dry: the more you scoop, the more it flows!” (p. 31; DZM, p. 23 (10)) This moment is all the more significant as the stream flows in the old bed of the Yellow River, the very source of inexhaustible Chinese civilisation.

After this, a blood craze breaks out: blood collection multiplies, first through various public channels, then by private “bloodheads,” in particular the narrator’s 23-year-old father Ding Hui. The main part of the action takes place eight years after this episode, when people begin falling ill from “the fever” and dying like “leaves falling from the trees.” While the narrator’s grandfather (who is not infected), having learned about the nature of the illness, tries to organise the villagers who have contracted the virus, bringing them to live in the school and work together in an autonomous, cooperative way, his leadership is soon contested by his nephews, who are hungry for power and seek to recreate a political hierarchy with privileges for the leaders within the school. Others steal rice from the common food supplies or clothes from other sick people. When the narrator’s uncle finds love with another infected woman, Lingling (both are married), the new selfproclaimed leaders of the school issue Cultural Revolution-style regulations punishing adultery with public humiliation that involves parading around the village with a dunce’s cap and being doused with HIV-infected blood. The utopian community that might have been possible, Yan Lianke hints, when the terror inspired by the illness breaks down oppressive political and social structures, quickly gives way to routinisation, bureaucracy, and new forms of exploitation. This bureaucratic evolution has no positive side: there is no hospital, no medication, no insurance paid by the authorities; it is simply used as a pretext to exert power over the weakened villagers. Without care and medication, the villagers die off one by one, and at the end of the novel, when Ding Shuiyang, the grandfather, returns to the village from the city, all seem to have fallen victim to the illness and the political struggles that have accelerated its spread.

However, this storyline is only the outside shell of the novel. As suggested by the title, the narrative actually moves back and forth between the events described by the narrator and his grandfather’s many dreams. The importance of dreams is underscored by the biblical epigraph taken from the Old Testament story of Joseph, in which the Pharaoh’s dreams prefigure seven years of plague. It is regrettable that the French translator has chosen not to reproduce the distinction between bold and ordinary type that appears throughout the original version, and which structures the novel into more realistic and more dreamlike modes, although the barriers are fluid (another difficulty is that the chapters in translation are numbered straight through from 1 to 20, whereas in the original they are structured into 8 parts or juan). The very first dream passage in bold alludes to Yan’s original idea for the book:

Grandfather had been dreaming the same dream for three nights. (…) Under the towns of Weixian and Dongjing a network of pipes spread out like a spider’s web: in every pipe, blood was flowing. From the cracks where the pipes had been badly connected, and in places where they curved, blood sprayed out like water, spouting heavenwards and falling like crimson rain, the stench of red blood irritating his nose. And on the plain, grandfather saw that the water in wells and rivers was all flaming red, exuding a pungent smell of blood. (p. 8; DZM, p. 8)

Several other dreams expand on this theme: the dream of gold (Chapter 4 of the French version), the dream of the coffin factory (Chapter 5), and the dream in which all trees are cut down to make coffins (Chapter 10). In these dreams, it becomes clear to the grandfather that his own son, Ding Hui, is responsible not only for the blood collection (the “dream of gold,” in which solid gold appears in all the fields where the peasants are working, waiting only to be picked up), but also for embezzling the money allocated by the government to provide free coffins for the dead (the coffin factory). By selling the coffins meant to be distributed for free, just as he has sold blood before, Ding Hui not only makes a fortune that allows him to buy a traditional courtyard house in the district town, with a safe in which he keeps millions in 100-yuan bills, but also to ascend the government hierarchy to an unassailable position. At the end of the novel, he strikes on a third gold mine: arranging marriages in the afterlife by “selling” dead people for a high fee. Worse yet, he does not hesitate to use his own dead son to “buy” into an alliance with the district secretary: he betroths the latter’s dead daughter (who, we are told, suffered from a limp and mental deficiency) to Ding Qiang, whose remains are exhumed to be lavishly reburied, far from home, with a photograph of the young woman.

At this point the grandfather draws the line: after his grandson repeatedly appears to him in his dreams, protesting bitterly against his forced remarriage in the nether realm, he finally uses a chestnut wood truncheon to kill his own son(11) – though not until after the reburial has been carried out. For this he is briefly arrested, and as he returns from prison to the village, the reader realises that this is the same event narrated in the first pages: the whole novel is a flashback. The grandfather remains alone, facing the desolation of the Great Central plains that stand for Chinese civilisation itself:

In each village, the houses were still there, but not a tree. They had all been cut to make coffins. (…) The plain was completely bald, all human beings and animals were dead. (p. 325; DZM, p. 284)

Yet the book ends with a glimmer of hope: in a torrent of cleansing rain, the grandfather sees a woman throwing up mud with a willow stick, thus shaping innumerable human figures who dance before his eyes. This ending is very difficult to interpret. Yan Lianke has shown skilfully how even within the calamity of the HIV infection, a space can be created for hope and for reinventing new forms of life in common, even of love (the narrator’s uncle and Lingling). In his interview, Yan speaks with conviction about the discrete but impressive resistance of the peasants of Henan: “They just continued to work in the field and they sat still and ate their bowl of rice in front of the door at home.”(12) At the same time, he highlights that mass death is no impediment to characters such as Ding Hui, who will use it to obtain wealth and power by selling not only blood, but also government- granted coffins and even dead relatives. The political system that provides incentives for such action, although not explicitly taken to task, certainly does not come away unscathed. Nonetheless, there is no moralising and no fingerpointing: in what some may see as an act of selfcensorship, the readers are left to draw their own conclusions.

In his postscript, which is entitled “The collapse of literature” (Xiezuo de bengkui, p. 286; the title is unfortunately omitted in French), Yan adds that even he found himself perplexed and crying the day he finished writing:

I couldn’t say why I felt such sadness. For whom was I crying? Why was I experiencing a previously unknown despair and helplessness? For my own life? Or for the world I live in? Or was it for Henan—my homeland—and for all the other provinces and places filled with calamity and suffering where innumerable AIDS sufferers were living their lives? Or could it be for the dead end my writing might be facing after finishing The Dream of Ding Village, because I had expended all psychological forces? (p. 325; DZM, p. 287)

There is no simple answer to these questions, except that all hypotheses probably apply equally. The radical quality of Yan Lianke’s writing does not spare even the author himself, when he goes so far as to suspect his own suffering of being triggered by narcissism. This is no doubt why the narrator is a dead child, the only figure that can truly appear “innocent.” Carlos Rojas, in a perceptive review, concludes by asking whether the grandfather is locked in a state of melancholy or whether he can start rebuilding new attachments and institutions, having gone through a stage of mourning.(13) Yet the grandfather remains a problematic figure, having himself initiated the blood craze by scooping up the bowl of water from the Yellow River, and taking justice into his own hands by killing his son to avenge the displacement of his grandson’s grave. The reader is surely not expected to condone such vengeance. No character comes away unscathed from the scandal: in this respect the implicit political responsibilities are only part of a more general moral and human breakdown in values. By concluding with the image of clay figures dancing on the Central Plains, which speaks both to Chinese creation mythology and to the Biblical epigraph, Yan Lianke is probably suggesting that humanity itself has fallen victim to the events that are alluded to in the book, and that humanity itself needs to be reshaped and rethought.