BOOK REVIEWS

Beijing’s “Rule of Law” Strategy for Governing Hong Kong: Legalisation without Democratisation

IntroductionSince the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China, the central government has continuously emphasised the importance of respecting, and adhering to, the rule of law as provided in the Basic Law, in particular in governing Hong Kong issues. It has consistently made the claim that Beijing and the Hong Kong government have largely operated within the parameters of the Basic Law. Undoubtedly, the Basic Law has been actively litigated in Hong Kong courts, and the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee (NPCSC), as the highest organ of state power in the Chinese constitutional structure, have made interpretations of, and decisions in relation to, the Basic Law to give meanings to provisions therein to settle important disputes. The Basic Law has become the focal point in governing the growing interaction between China’s legislature and Hong Kong courts and between Hong Kong’s common law system and China’s civil law system. For the central authorities, the Basic Law is not a sham constitutional document, a window dressing that can be easily swept aside and ignored. Instead, the Basic Law forms the foundation for the constitutional design of “one country, two systems.” Nevertheless, in response to the changing socio-political landscape of Hong Kong in the past decades, the central government has resorted to aggressive legality in managing increasing pro-democratic activism and ever-deepening divisions in Hong Kong society. At several critical junctures, the central government has efficiently used legal mechanisms as established by the Basic Law to neutralise political resistance, to resolve thorny issues, and to stifle pro-independence voices. Legal mechanisms have been effectively employed to legitimise the stance of the central government on the pace and depth of democratic reforms in Hong Kong. In this sense, the Chinese government seems to have successfully assimilated the strategy of the British government to “regain legitimacy without (full) democratisation” (Delisle 2007) during the colonial era. China’s aggressive legality has caused serious concerns in the local and international communities. The prevailing perception is that imposing the legality of the Chinese way will eventually put Hong Kong’s liberal legal order at existential risk, and legitimise China’s political interference in the name of law (Yu 2017: 60). The rule of law in present-day Hong Kong presents a complicated puzzle. It is not enough to simply laud the 20-year implementation of the Basic Law or to demonise Hong Kong just because of the looming shadow of authoritarian China. There is abundant literature on the evolution of political strategies in Beijing’s governance over Hong Kong (e.g., Kwong 2018; Fong 2015; Lau 1988), but rarely from a legal perspective. Questions with regard to how the central government has deployed the law to govern Hong Kong and the impact of Beijing’s “interference” in Hong Kong’s legal affairs de-serve more nuanced analysis. This article will examine the evolution and effects of legal strategies that the central government has used in managing Hong Kong affairs. By evaluating the influences of Beijing’s legal discourses and strategy over Hong Kong’s legal community, it highlights the dilemma of their struggle between the thin and thick versions of the law and poses the question of whether Hong Kong’s liberal common law system can amicably coexist with an authoritarian central authority. The central argument is that over the past thirty years, under the entrenched “legalisation without democratisation” strategy, Beijing’s legal strategies for Hong Kong have become more hands-on and assertive, often at the expense of some core values in Hong Kong’s rule of law. The flaws and instrumentalism of Chinese-style “rule of law,” or rule by law, have become increasingly salient, giving rise to deepening conflicts with the Hong Kong common law system. Under Beijing’s legal strategies, the law in Hong Kong continues to serve as the handmaiden for a flourishing market economy but as an obstructer of liberal political pluralism. Legalisation without democratisation has given rise to a worrying trend of rising authoritarian legalism in Hong Kong. Political and rule-of-law advocates in Hong Kong have begun to share the same fate as their mainland counterparts – struggling between rule by law, which emphasises the formalistic and technical sides of legality, and the version of thick rule of law with democratic morality.

Historical review: The rise of authoritarian legalism and conflicts between two legal systems

Law is always intertwined with politics, and this is particularly the case with the Basic Law. In post-1997 Hong Kong, three critical junctures mark turning points in the Beijing government’s ruling policy over Hong Kong: the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, the 1 July 2003 protest against the Article 23 legislation, and the 2014 Occupy Central Movement (OCM). The 1989 event cemented Beijing’s hostility toward a fully democratised HKSAR and gave rise to long-term distrust between Beijing and the pro-democracy camp. The massive 2003 protest prompted Beijing to change its governing strategy from self-restrained non-interference to a more active posture. This new strategy generated an unexpected impact on the relationship between the mainland and Hong Kong, and increased confrontations between the two legal systems. To resist the erosion of its high degree of autonomy and the stifling of democratic development, Hong Kong’s civil society initiated a series of public protests and campaigns, which culminated in the 2014 OCM and the ultimate rise of the pro-independence ethos. These “[p]opular protests have generally had a correlation with Central Government interference to advance its preferences” (Davis 2015b: 295). In responding to the OCM and pro-independence activism, Beijing turned to a sovereignty discourse and multiple actions to further restrain the political space in Hong Kong. In the post-OCM era, Beijing has proactively promoted the “integration” strategy that was initiated in 2003. Coupled with the changing governing strategies, Beijing also adjusted its legal discourse and action. Although “legalisation without democratisation” has remained the central feature characterising Beijing’s strategy over Hong Kong from the outset, Beijing has turned from a hands-off non-interference policy to a more hands-on, assertive stance in legalising its authority over Hong Kong. Influenced by Beijing’s hardening legal measures, Hong Kong has witnessed the potential rise of authoritarian legalism, as the central and local authorities have increasingly used the institutions and mechanisms of law to bolster their exercise of power and curtail political opposition.

1989 June Fourth Incident: The adoption of the“legalisation without democratisation” strategy and mutual-non-interference policy

In designing the political system for post-1997 Hong Kong, Beijing intentionally inherited the colonial political-economic system without any at-tempt at full democratisation (Deng 1987). However, in the 1980s the decolonisation process itself triggered pro-democracy demands in Hong Kong civil society and bottom-up pressure for more democratic input into the Basic Law (Ma 2017). During the drafting of the Basic Law, pro-democracy forces actively bargained for full democracy while Beijing opted for slow-paced, limited democratisation, but the two sides managed to maintain a relatively amicable relationship, partly because the latter regarded the democrats as “patriots” who supported the transfer of sovereignty, and partly because the democrats were not politically influential and were not perceived as a political challenge. The 1980s also witnessed a relatively open environment regarding political reform in the mainland. Some open-minded central leaders, such as Hu Qili, even championed freedom of speech in Hong Kong. Hu once urged mainland officials to consider allowing Hong Kong newspapers and magazines to enter the mainland after 1997 and to reform media regulation in the mainland (Wu 1998: 31). This liberal-minded attitude was never seen again after 1989. As many have noted, the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown was a major watershed for democratic development in Hong Kong. The event also had a significant impact on the drafting of the Basic Law as tension and distrust intensified between Beijing and the pro-democracy camp. After the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, Beijing took a tougher approach with regard to Hong Kong affairs and a more cautious attitude toward full democracy, in fear that democratisation in Hong Kong would effect political change in the mainland. The tougher stance was best illustrated by the different versions of Article 23 of the Basic Law before and after the Tiananmen crackdown (Petersen 2005: 17-20).[1] It was in this period that Beijing coined the famous maxim “the well water does not intrude on the river” (jingshui bufan heshui 井水不犯河水) (ibid.: 18), i.e., a policy of separation and mutual non-interference. It was also viewed as a “veiled threat that Hong Kong should not become involved in mainland politics.”[2] Since the 1989 crackdown, the “legalisation without democratisation” strategy has become entrenched as one of the national strategies for both Hong Kong and the mainland. Since the promulgation of the Basic Law, the central government has frequently used it as the basic anchor for espousing rule of law – legal mechanisms were designed from the outset to control the pace of democratisation, to limit the space of democracy, and ultimately to prevent Hong Kong from becoming a base for subverting the socialist system in the mainland.

July 1 2003 protest and Article 23 legislation: From non-interference to the assertion of the central authorities

Right after the 1997 handover, the HKSAR immediately confronted constitutional and legal issues regarding interpretation of the Basic Law (Chen 2007: 167). While the 1999 NPCSC interpretation signified the first formal legal interaction between the central government and HKSAR, the central government largely maintained a self-restrained attitude towards Hong Kong governance up until 2003. However, the 1999 NPCSC interpretation, although issued in a responsive way, set a precedent for the central government to use constitutional interpretation to address Hong Kong’s rule of law concerns. Basic Law interpretation has become the most common, if not the only, legal method Beijing uses to interact with Hong Kong on core issues relating to implementation of the Basic Law. The 1999 NPCSC interpretation provoked the first protest by legal professionals in Hong Kong, who criticised the interpretation as being done at the expense of judicial independence and at great social cost (Chan 2014: 177). Although the event itself did not fundamentally change Beijing’s governing strategies, it signalled to the legal communities in both Hong Kong and the mainland where potential pressure points and conflict might lie in the interaction of two different legal systems. After the 1999 NPCSC interpretation, the Standing Committee did not issue any interpretation until 2004. However, the march on 1 July 2003 against the national security bill marked a dramatic turning point for Beijing’s strategy in governing Hong Kong. Under Article 23 of the Basic Law, Hong Kong is duty-bound to enact local legislation to safeguard China’s national security. The Beijing authorities demanded initiation of the legislative process but left the process entirely to Hong Kong, as stipulated in the Basic Law. The proposed Article 23 legislation triggered widespread discontent, resulting in an unprecedented street protest by an estimated 500,000 people. Beijing, on the other hand, regarded the protest as a sign that “Hong Kong people’s hearts haven’t re-turned to the motherland,” and a strong sense of betrayal and fear that Hong Kong was slipping away led the Central Government to abandon its non-interventionist stance and adopt a policy of “doing what should be done while leaving the rest alone” (yousuowei, yousuobuwei 有所为,有所不为).[3] After the massive march, the Central Hong Kong and Macao Work Coordination Group of the Chinese Communist Party was set up, headed by the highest central leadership (Lo 2007: 179). A series of measures was initiated, aimed at boosting the Hong Kong economy and facilitating the integration of Hong Kong with the mainland. The central government, particularly the Liaison Office, increased its presence and capacity in Hong Kong, and as a result, its influence in the political arena started to grow (Cheung 2012: 324). Correspondingly, the Beijing authorities and pro-establishment legal scholars also tried to reshape Basic Law discourse to serve the new governing strategy. For instance, in 2004, the Beijing and Hong Kong authorities began to emphasise the notion of “executive-led government,” which is not ex-plicitly prescribed in the Basic Law. The stress on “executive-led government” is closely related to affirming the central government’s power over Hong Kong (Chen 2005: 10). Another Basic Law discourse constructed and re-emphasised by Beijing was the supervisory power of the NPCSC over the HKSAR,[4] which was later formally adopted in a 2014 White Paper.[5] During the ten-year period between 2003 and 2013, the NPCSC issued three more interpretations: the 2004 Interpretation on Hong Kong’s political reform, the 2005 Interpretation on the term of the Chief Executive (CE) of the HKSAR, and the 2011 Interpretation on the Congo Case (see Table 1). The 2005 and 2011 interpretations were both issued on the request of the HKSAR, and the 2004 interpretation was initiated by the NPCSC. Despite the limited number of such cases, interpretation of the Basic Law has become a battlefield for defining autonomy (Chan 2014: 177). The promulgation of the 2004 Interpretations reflected the failure of the 1 July 2003 march to pressure Beijing into offering a compromise on political reform, despite some perceived concessions that were made such as suspension of the Article 23 legislation and the resignation of the then Chief Executive. The 2004 NPCSC interpretation, reflecting a more assertive central government, not only denied the 2007/8 universal suffrage scheme but also set out specific and stricter procedures for Hong Kong’s political re-forms than what was originally proscribed in the Basic Law. The 2004 NPCSC Interpretation, along with the 2007 NPCSC decision,[6] controlled and curbed the pace of universal suffrage reform in Hong Kong. As Chan perceptively pointed out, the NPCSC conveyed a clear message that Beijing is in control of Hong Kong’s democratic development. “The central government is not content with just having a veto power to disallow any political change, but wants full control to decide whether any change is proposed in the first place (Chan 2014: 177).”

2014 Occupy Central Movement: Enhancing constitutional integration

Although Hong Kong has gone one step forward in democratisation thanks to the 2012 election reform resulting from compromises between Beijing and the pro-democratic parties in 2010, it is still far from the universal suffrage demanded by the pro-democracy bloc. In January 2013, Benny Tai publicly put forward the idea of “Occupying Central” to mobilise public sup-port for genuine universal suffrage.[7] (7) Since then, unprecedented wrestling has occurred between Beijing and pro-democratic forces as well as between the legal communities in Hong Kong and the mainland. The central authorities have persistently taken a hard-line stand since the initiation of the OCM. On 10 June 2014, China’s State Council for the first time issued a white paper on the Hong Kong issue, which officially proclaimed that the central government has “plenary power to govern Hong Kong.”[8] The concept was later adopted in Xi Jinping’s report to the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (NCCPC) in 2017.[9] Following the white paper, on 31 August 2014, the NPCSC issued a decision (commonly known as the 831 decision), which laid down a highly restrictive and conservative scheme for the 2017 election of the Chief Executive and de facto barred all opposition candidates from running for the position of CE.[10] The white paper and the 831 decision were fiercely criticised by many Hong Kong academics and activists for trampling on the Basic Law and the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration. This ultimately triggered the OCM and the rise of pro-independence activism following the failure of the OCM (Davis 2015a: 107-9). Before and throughout the OCM, the unlawful nature of civil dis-obedience was one of the focal points of attack by Beijing (Zhu 2017: 168), which portrayed itself as the firmest defender of Hong Kong’s rule of law. Like the 2003 march, the OCM also failed to pressure Beijing into making any concessions on democratic reform. In response, more radicalised pro-independence activism emerged in the post-OCM period, significantly changing Hong Kong’s political and legal dynamics. In addressing pro-democratic forces and pro-separatism localists, Beijing has adopted different attitudes (Kwong 2018) as well as legal tactics. Despite its strong condemnation of the OCM, in the post-OCM period Beijing has largely left OCM-related cases to the Hong Kong judiciary, and the central government has rarely directly interfered with OCM-related trials. Despite criticism of some cases from both the establishment and pro-democratic blocs, the independence and neutrality of the courts have been largely recognised by mainstream legal professionals in Hong Kong.[11] While a few scholarly articles and pro-Beijing media comments were critical of judgements in some high-profile cases and cast doubt on the political values of foreign judges, specifically in the “seven policemen” case,[12] such criticisms were quickly refuted by leading figures in Hong Kong’s legal community and were firmly rejected in practice when the terms of three foreign non-permanent CFA judges were extended in 2018.[13] By contrast, the central government has taken a much tougher stance to-ward pro-independence activists and has aggressively and controversially used the law as a potent arsenal to prevent pro-independence activists from entering formal political institutions and from gathering further political momentum (see Yuen and Chung 2018). Two elected pro-independence LegCo members were unseated for failing to properly swear allegiance to the HKSAR and to maintain the Basic Law at their LegCo inauguration. Subsequently, four other pan-democratic LegCo members were also disqualified for their disputed manner of oath-taking, emasculating the majority veto power that the pan-democratic bloc has always had in LegCo.[14] Despite being a highly charged political matter, the 2016 oath-taking contention was swiftly resolved by a combination of legal measures employed by the Hong Kong and central authorities and endorsed by the courts. The HKSAR administration successfully initiated a time – and money – consuming judicial review process to disqualify non-establishment political rivals on a highly selective basis. Delivering a fatal blow to pro-independence activism, the NPCSC issued its most controversial interpretation in the middle of a trial, specifying the requirements for valid oath-taking and for any candidates interested in running for public office. That interpretation not only had a direct impact on the oath-taking cases but also bars any other candidates who would challenge China’s sovereignty over Hong Kong. The legality and authority of the controversial NPCSC interpretation were fully embraced by the Hong Kong courts, and the interpretation was relied on as the legal basis for disqualifying LegCo members.[15] The 2016 NPCSC interpretation clearly shows the central government’s red line and its determi-nation to aggressively intervene in matters relating to sovereignty. When facing growing separatism in Hong Kong that challenges China’s territorial integrity, Hong Kong’s judicial independence and the rule of law are secondary concerns at best. Facing the central government’s zero tolerance policy for separatism, the Hong Kong government has utilised various legal technicalities, which had been rarely used in the past, to crack down on pro-independence activism. In 2016, many pro-independence localists running in the LegCo election were stopped at the starting line as returning officials disqualified them on the basis of their political positioning.[16] Pro-independence groups and po-litical parties were not only prevented from registering under the Societies Ordinance but were outlawed by the government.[17] Localist activists involved in the Mong Kok riot received unprecedentedly heavy sentences on conviction.[18] It is fair to say that legal mechanisms have been fully explored and utilised, controversially in many cases, to address Beijing’s biggest concern over the separatism issue. Such use, or abuse, of the law bears some similarity to the widespread use of legalism in many authoritarian regimes where governments have sought to use the law to “suppress dissent in al-most all forms while maintaining legal and political credibility” (Gurnham 2012). The law itself has been deployed as a political instrument to intimidate political undesirables. Another salient change in the post-OCM period was the emergence of constitutional discourse, which aims to serve the strategy of further integrating Hong Kong into China, economically, socially, and legally. The change in tone has been reflected in official documents. The 1990 decision issued by the NPC on the Basic Law proclaimed that the Basic Law “is constitutional, [the] systems, policies and laws to be instituted after the establishment of the HKSAR should be based on the Basic Law.”[19] From 2002 to 2014, reports made by the general secretary of the CCP to the NCCPC[20]and government reports to the NPC all used the phrase that the central government would “act in strict accordance with the Basic Law.”[21] It was in the 2015 government report that “the PRC Constitution” was added be-fore the Basic Law so that the statement reads: the central government would “act in strict accordance with the Constitution and Basic Law.” Since then, this phrase has been frequently used in official document.[22] Some officials and mainland scholars have further developed the constitutional discourse by elaborating on the effect of the PRC constitution in Hong Kong and how it should be applied.[23] The change in legal discourse reflects an increasing assertion of central authority over Hong Kong. If the concept of “executive-led government” allows the central authorities to rule through Hong Kong’s political institutions, the concepts of “plenary power to govern Hong Kong” and “the applicability of the PRC Constitution in Hong Kong” imply the possibility and necessity of direct rule by central authorities in Hong Kong, parallel to Hong Kong’ autonomous political system. Although the applicability of the PRC Constitution in Hong Kong is highly controversial, the constitutional integration discourse may be translated into concrete actions such as China’s National Security Law in 2015, which for the first time includes Hong Kong and Macau in national legislation. The constitutional discourse may also serve to legitimise measures aimed at further integrating Hong Kong into the mainland (e.g., the joint rail checkpoint and the Greater Bay programme), to enhance the authority of NPCSC Interpretations and decisions, and to assert potential influence on judges’ understanding and application of relevant mainland laws. The new legal discourse that emphasises the effect of the PRC Constitution not only echoes but also further entrenches the “legalisation without democratisation” strategy. The constitutional discourse requires residents of Hong Kong to respect, or at least not to interfere with, the socialist system and Party-state rule in the mainland. The recognition of the legality of one-party rule in China, including Hong Kong, may set up legal obstacles to pro-democratic campaigning and fundamental freedoms in Hong Kong, since one-party rule is the very opposite of Hong Kong’s democratic aspirations. The issue has loomed ever larger since the amendment of the PRC Constitution in 2018, which added the Party’s leadership into the body text of the Constitution. The constitutional integration discourse in Hong Kong may create a political atmosphere that would foster the rise of local authoritarian legalism, as its chilling effects have already been shown in Hong Kong in the heated debate over whether politicians who are critical of one-party rule should be banned from seeking political office.[24] It is also a question of whether pro-democratic forces can continue their anti-Party advocacy and activism, not to mention pro-independence activism that undermines the sovereignty principle. Since the initiation of constitutional dis-course, anti-authoritarianism activism and speeches that used to be common practice have become controversial and uncertain. The hegemonic use of “constitution” and “rule of law” rhetoric is also commonly seen in many authoritarian states where the government has used similar legal discourse to justify authoritarianism and make it difficult for the opposition to challenge the ruling authority as repressive legal measures have emerged within constitutional framework (Rajah 2014: 55-64; Corrales 2015: 40). In fact, the effect of the PRC Constitution was discussed at an early stage in the drafting of the Basic Law. How to accommodate “one country, two systems” into China’s socialist constitutional framework was a controversial issue without a clear answer (Epstein 1989: 49-50). Scholars’ opinions on that issue have changed depending on the evolving political dynamic (Cao 2018). As Cao Xudong (2018: 82) pointed out, in the first few years following the handover, most scholars generally equated implementation of the Basic Law with the implementation of the PRC Constitution in Hong Kong. Therefore, the entire Constitution is valid in Hong Kong only through the vehicle of the Basic Law, and it is not necessary to apply any specific pro-visions of the Constitution to Hong Kong. However, since the fomenting of the OCM and the rise of pro-independence activism, constitutional dis-course has changed dramatically. Many mainland scholars, in tune with the official agenda, have turned to stressing the effect of the PRC Constitution in Hong Kong and have even argued that constitutional provisions should apply to Hong Kong (Cao 2018: 82-3). In the three decades since the “one country, two systems” concept was put forward, the ideological and legal discourses have shifted from explaining and justifying “how a capitalist territory will be legislated into existence by and within a socialist country” (Epstein 1989: 49-50) to how a socialist constitution can be accommodated in a capitalist and common law territory.

Effect of Beijing’s legal strategies

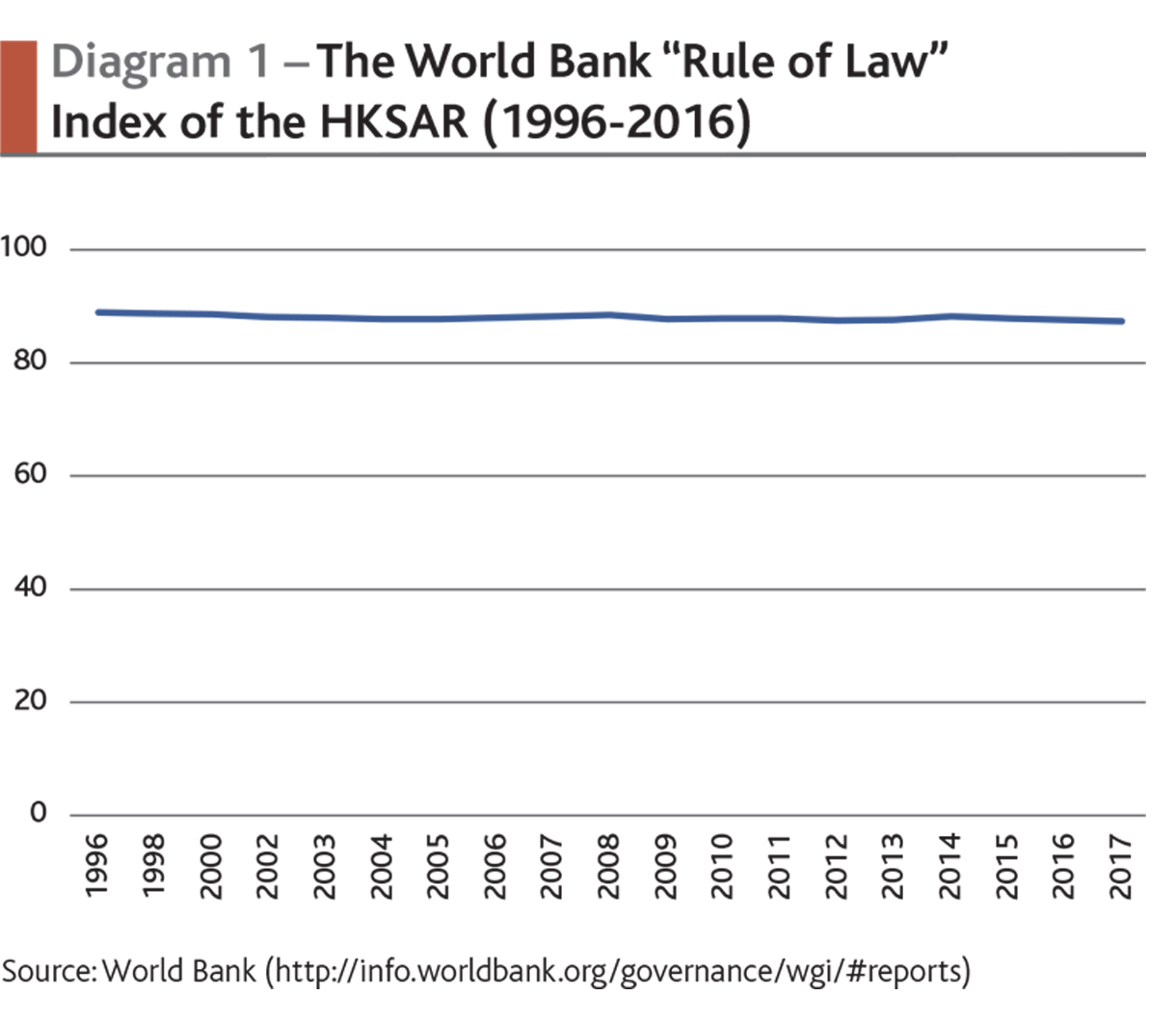

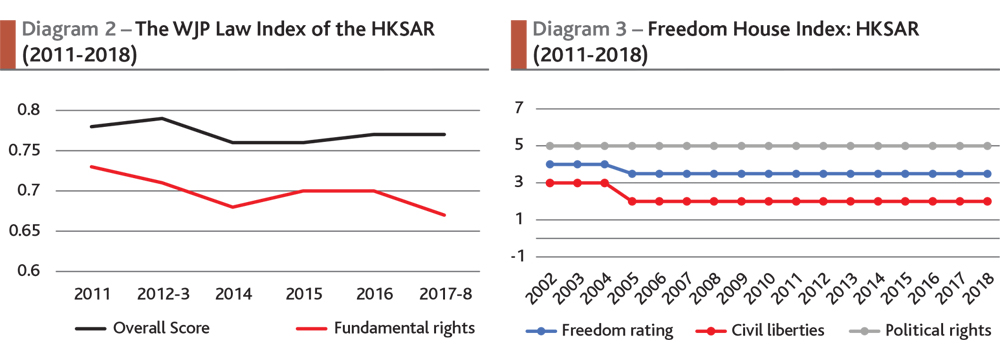

The question of whether and how the central government’s aggressive legalism has adversely affected Hong Kong’s rule of law permits no simple answer, given the lack of empirical studies. Despite a series of controversial events and conflicts with the central authorities, most prominent Hong Kong judges have strongly affirmed the good maintenance of rule of law in Hong Kong in the post-1997 period (Neuberger 2014; Mason 2011; Yu 2017: 60). But others in the legal community disagree, worrying about “storm clouds on the horizon” (Bokhary 2013: 590) or expressly pointing out the retrogression of Hong Kong’s rule of law, particularly in political and civil rights.[25] Useful data shed light on the state of affairs of rule of law in Hong Kong. According to the World Bank rule of law index, Hong Kong’s rule of law has maintained approximately the same high level since 1996 (see Diagram 1), which is echoed by three other prominent rule of law indicators provided by the Heritage Foundation,[26]Freedom House, and the World Justice Project.[27] Nevertheless, the sub-indicator of the World Justice Project (WJP) rule of law index shows that fundamental rights in Hong Kong have obviously deteriorated since 2011 (Diagram 2).

The combination of the four rule of law indexes is largely consistent with the general perception of rule of law development in Hong Kong: the rule of law remains strong in respect to protecting property rights and maintaining social order, as shown by the World Bank (Diagram 1) and Heritage indexes, which emphasise these two functions of the rule of law; fundamental rights have exhibited a deteriorating trend according to the WJP Index (Diagram 2); and democratic development remains stagnant, as shown by the Freedom House Index (Diagram 3), which stresses democratic development. The data to a certain extent prove the success of Beijing’s legal strategy, i.e., maintaining a high level of rule of law in the conservative pro-capitalist and pro-market dimensions, supplemented by a still high but selective guarantee of civil rights with little democratic input. The dynamics of Hong Kong’s rule of law bear the distinctive feature of authoritarian legalism: “the capacity of the state to provide an arena of private law without any expansion of the public sphere” (Jayasuriya 2001: 120). The law serves as a handmaiden for a flourishing market economy but not as the facilitator of liberal political pluralism.

The combination of the four rule of law indexes is largely consistent with the general perception of rule of law development in Hong Kong: the rule of law remains strong in respect to protecting property rights and maintaining social order, as shown by the World Bank (Diagram 1) and Heritage indexes, which emphasise these two functions of the rule of law; fundamental rights have exhibited a deteriorating trend according to the WJP Index (Diagram 2); and democratic development remains stagnant, as shown by the Freedom House Index (Diagram 3), which stresses democratic development. The data to a certain extent prove the success of Beijing’s legal strategy, i.e., maintaining a high level of rule of law in the conservative pro-capitalist and pro-market dimensions, supplemented by a still high but selective guarantee of civil rights with little democratic input. The dynamics of Hong Kong’s rule of law bear the distinctive feature of authoritarian legalism: “the capacity of the state to provide an arena of private law without any expansion of the public sphere” (Jayasuriya 2001: 120). The law serves as a handmaiden for a flourishing market economy but not as the facilitator of liberal political pluralism.

As Davis pointed out, the “legalisation without democratisation” strategy has deepened Hong Kong and international society’s distrust of the Chinese government’s commitment to carrying out the letter and spirit of the Basic Law and the Sino-British Joint Declaration. While the central government has adopted an aggressive approach to employing the law to curb the pace of democracy in Hong Kong, it is inevitably eroding Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy along with the core values that are identified with the common law rule of law tradition (Davis 2015b: 296). In addition, the “legalisation without democratisation” strategy could also generate the following side effects, which are probably beyond the central government’s expectations.

First, it continuously creates a legitimised gap for pro-democracy momentum. The Basic Law not only explicitly makes a promise of evolving toward, though progressively, a democracy with evident liberal democratic values but also prescribes specific procedures to fulfil this promise. However, in practice, in order to slow down the pace of democratisation in Hong Kong and to take the driver’s seat, the central authorities have interpreted the core elements of democratic reform, such as “institutional selection” (jigou xuanju 机构选举), the five steps required for passing a suffrage reform scheme, and the legal discourse calling for “localised democracy” as opposed to that of Western countries. Through a series of aggressive interpretations, the central authorities have taken power away from Hong Kong in defining the pace and meaning of democracy. Like the hybrid constitutions of other authoritarian regimes, the gap between the democratic undertakings pre-scribed in writing and the failure to fulfil them generates continuous demand and catalyses pro-democracy momentum for political movements such as the OCM.

Second, “legalisation without democratisation” has given rise to unforeseen disillusionment with the law and significant radicalisation of the democratic movement into pro-independence activism that aims to overthrow the existing constitutional arrangement. The “legalisation” strategy that excludes moral input delegitimises the role of law in a changing society. Since the central government and Hong Kong legal institutions have used legal mechanisms and discourses politically and opportunistically to criminalise social movement participants and crack down on opposition politicians, it seems increasingly difficult for pro-democracy forces (not to mention pro-independence activists) to pursue their causes within the current legal framework. Their confidence and enthusiasm for using the courts as a crucial battlefield for their causes in the early years after 1997 (Tam 2013: 124-5) seem to have waned after encountering increasing difficulty in trying to translate political pursuits into legal action. Criticism of the “conservative” nature of the law has naturally arisen in Hong Kong, with some aggressive legal professionals arguing that rule of law can no longer be meaningfully discussed without referring to politics,[28] which ironically echoes the Marxist view of law as well as Schmidt’s that has been widely cited by many mainland scholars to endorse Party-state rule. While some of the pro-democracy forces in Hong Kong doubt the law’s usefulness in promoting democratic change, some mainland scholars also point out the law’s conservative nature and its limited ability to respond to the changes Hong Kong society needs to make (Zheng 2017: 26). Although the two sides have different agendas and take distinct moral stances, both question the function of law in a society facing political challenges. Ironically, the rule of law underpinned Hong Kong’s past success and now it is the Beijing authorities who appear to be the firmest and fiercest defenders of the law (and order). Naturally, the legality embraced by the authoritarian government has further fuelled suspicion about the value of law and the judiciary in the pursuit of democracy.

It is interesting to note that both “legalisation without democratisation” and the recent “constitutional integration” effort, to a great extent, consciously or unconsciously, follow Britain’s footsteps during the colonial period. The successful transplant of the common law in Hong Kong contributed to Britain’s successful governing of Hong Kong without implementing democracy. There has been a growing realisation among mainland scholars of the remarkable achievement of the common law in Hong Kong’s good governance and its influence in shaping the rule of law cultural mentality (Zheng 2017). The Chinese government obviously has drawn on the British experience in designing the political system for post-1997 Hong Kong, as Chinese officials and law makers have publicly admired the successful model of British governance marked by robust economic-social development with an apolitical society, and they intended to maintain the colonial capitalist economic system by institutional design under the Basic Law (Kuan 1998: 1424). So far, the continuing “legalisation without democratisation” strategy has been relatively successful for Beijing, as manifested in the effective control of the pace of democratisation, the handling of the OCM, and the suffocation of pro-independence activism.

It should be noted that, despite the dazzling legal saga of the past thirty years, the core interests and bottom-line of the central government in implementing the Basic Law have remained unchanged since 1989, i.e., to maintain state sovereignty and national security (including safeguarding the Party-state regime), to curb full democratisation in Hong Kong, and to maintain the prosperity and stability of Hong Kong (Yang 2013: 71).[29] The conflicts between Beijing and Hong Kong and the issues that have invited Beijing’s intervention illustrate well what concerns the central government the most (see Table 1). Over the past 30 years, changes in the central government’s legal tactics appear to have been made in response to the changing situations in Hong Kong society, but upon closer examination, they all revolve around the aforementioned core interests of Beijing. These core interests determine when and how the central government intervenes in disputed issues.

In some circumstances when core interests were involved, extra-legal or illegal measures were even taken, significantly impairing Hong Kong’s rule of law. The most striking cases were the forced disappearance of five Causeway Bay booksellers and the Chinese billionaire Xiao Jianhua. Compared to legal measures allowed by the Basic Law, those extra-legal measures, which go against the “legalisation without (full) democratisation” principle, easily undermine the legitimacy of Beijing’s governance over Hong Kong and cast doubts on Beijing’s sincerity in complying with the Basic Law. Therefore, the Beijing authorities are still largely constrained from using such measures, despite their convenience and effectiveness.[30] Beijing has also used other soft lawful measures, mostly political and economic, that have yielded ripple effects on freedom of speech and freedom of association in Hong Kong, such as gradually squeezing out independent publications through the purchase of media and publishers in Hong Kong by Chinese buyers,[31] high-profile official criticism and media attacks to put pressure on progressive academics (Chan and Kerr 2016), and supporting various pro-Beijing civil organisations to counteract the opposition (Kwong 2018).

First, it continuously creates a legitimised gap for pro-democracy momentum. The Basic Law not only explicitly makes a promise of evolving toward, though progressively, a democracy with evident liberal democratic values but also prescribes specific procedures to fulfil this promise. However, in practice, in order to slow down the pace of democratisation in Hong Kong and to take the driver’s seat, the central authorities have interpreted the core elements of democratic reform, such as “institutional selection” (jigou xuanju 机构选举), the five steps required for passing a suffrage reform scheme, and the legal discourse calling for “localised democracy” as opposed to that of Western countries. Through a series of aggressive interpretations, the central authorities have taken power away from Hong Kong in defining the pace and meaning of democracy. Like the hybrid constitutions of other authoritarian regimes, the gap between the democratic undertakings pre-scribed in writing and the failure to fulfil them generates continuous demand and catalyses pro-democracy momentum for political movements such as the OCM.

Second, “legalisation without democratisation” has given rise to unforeseen disillusionment with the law and significant radicalisation of the democratic movement into pro-independence activism that aims to overthrow the existing constitutional arrangement. The “legalisation” strategy that excludes moral input delegitimises the role of law in a changing society. Since the central government and Hong Kong legal institutions have used legal mechanisms and discourses politically and opportunistically to criminalise social movement participants and crack down on opposition politicians, it seems increasingly difficult for pro-democracy forces (not to mention pro-independence activists) to pursue their causes within the current legal framework. Their confidence and enthusiasm for using the courts as a crucial battlefield for their causes in the early years after 1997 (Tam 2013: 124-5) seem to have waned after encountering increasing difficulty in trying to translate political pursuits into legal action. Criticism of the “conservative” nature of the law has naturally arisen in Hong Kong, with some aggressive legal professionals arguing that rule of law can no longer be meaningfully discussed without referring to politics,[28] which ironically echoes the Marxist view of law as well as Schmidt’s that has been widely cited by many mainland scholars to endorse Party-state rule. While some of the pro-democracy forces in Hong Kong doubt the law’s usefulness in promoting democratic change, some mainland scholars also point out the law’s conservative nature and its limited ability to respond to the changes Hong Kong society needs to make (Zheng 2017: 26). Although the two sides have different agendas and take distinct moral stances, both question the function of law in a society facing political challenges. Ironically, the rule of law underpinned Hong Kong’s past success and now it is the Beijing authorities who appear to be the firmest and fiercest defenders of the law (and order). Naturally, the legality embraced by the authoritarian government has further fuelled suspicion about the value of law and the judiciary in the pursuit of democracy.

It is interesting to note that both “legalisation without democratisation” and the recent “constitutional integration” effort, to a great extent, consciously or unconsciously, follow Britain’s footsteps during the colonial period. The successful transplant of the common law in Hong Kong contributed to Britain’s successful governing of Hong Kong without implementing democracy. There has been a growing realisation among mainland scholars of the remarkable achievement of the common law in Hong Kong’s good governance and its influence in shaping the rule of law cultural mentality (Zheng 2017). The Chinese government obviously has drawn on the British experience in designing the political system for post-1997 Hong Kong, as Chinese officials and law makers have publicly admired the successful model of British governance marked by robust economic-social development with an apolitical society, and they intended to maintain the colonial capitalist economic system by institutional design under the Basic Law (Kuan 1998: 1424). So far, the continuing “legalisation without democratisation” strategy has been relatively successful for Beijing, as manifested in the effective control of the pace of democratisation, the handling of the OCM, and the suffocation of pro-independence activism.

It should be noted that, despite the dazzling legal saga of the past thirty years, the core interests and bottom-line of the central government in implementing the Basic Law have remained unchanged since 1989, i.e., to maintain state sovereignty and national security (including safeguarding the Party-state regime), to curb full democratisation in Hong Kong, and to maintain the prosperity and stability of Hong Kong (Yang 2013: 71).[29] The conflicts between Beijing and Hong Kong and the issues that have invited Beijing’s intervention illustrate well what concerns the central government the most (see Table 1). Over the past 30 years, changes in the central government’s legal tactics appear to have been made in response to the changing situations in Hong Kong society, but upon closer examination, they all revolve around the aforementioned core interests of Beijing. These core interests determine when and how the central government intervenes in disputed issues.

In some circumstances when core interests were involved, extra-legal or illegal measures were even taken, significantly impairing Hong Kong’s rule of law. The most striking cases were the forced disappearance of five Causeway Bay booksellers and the Chinese billionaire Xiao Jianhua. Compared to legal measures allowed by the Basic Law, those extra-legal measures, which go against the “legalisation without (full) democratisation” principle, easily undermine the legitimacy of Beijing’s governance over Hong Kong and cast doubts on Beijing’s sincerity in complying with the Basic Law. Therefore, the Beijing authorities are still largely constrained from using such measures, despite their convenience and effectiveness.[30] Beijing has also used other soft lawful measures, mostly political and economic, that have yielded ripple effects on freedom of speech and freedom of association in Hong Kong, such as gradually squeezing out independent publications through the purchase of media and publishers in Hong Kong by Chinese buyers,[31] high-profile official criticism and media attacks to put pressure on progressive academics (Chan and Kerr 2016), and supporting various pro-Beijing civil organisations to counteract the opposition (Kwong 2018).

Influence over local legal communities: De-politicising or democratising the law?

Before the handover, Epstein (1989: 74) warned that mainland legal language, personnel, and the respective strengths of public policy and morality were potential, indirect influences that could imperceptibly change Hong Kong law. Another scholar forecasted that political rather than institutional factors may have a more significant influence on Hong Kong’s common law (Wesley-Smith 1989: 36). After 20 years, tangible factors such as language, personnel, and institutions are still limited in influencing Hong Kong’s legal system, while other imperceptible factors have become the major concern. The following section tries to explore whether and how the legal strategies of the central authorities have influenced the “common law mind” in Hong Kong, which is “a hardy locus of resistance to fundamental change” (Wesley-Smith 1989: 36). The two key questions addressed are whether the ethos of Hong Kong’s legal professionals has changed and whether the judiciary has become politicised under the shadow of China’s authoritarianism. The caste of lawyers and their modes of thought have been regarded as influential in Hong Kong as everywhere else in maintaining the common law system. When the legal profession in Hong Kong became exposed to wider ideas and new political tensions in the post-1997 period, the common law may have become more subject to non-traditional influences (Wesley-Smith 1989: 36). The impact of Beijing’s legal discourses, such as the emphasis on the effect of the PRC Constitution in Hong Kong, the rejection of Western-type democracy, and the supremacy of sovereignty, on the ethos of Hong Kong’s legal profession is difficult to gauge, for such change is prob-ably too subtle to perceive, given the lack of systematic study.[32] However, some trends may enlighten us on the matter. First, for pro-democratic legal professionals in Hong Kong, “legalisation without democratisation” has prompted the rise of cause lawyering. As Tam argued, the transfer of sovereignty and implementation of the Basic Law have encouraged lawyers to pursue political causes in their advocacy. The Basic Law, along with the Bill of Rights Ordinance, provides new legal openings for the first generation of lawyers to use courts as their battlefields, as both the administrative and legislative branches are designed to the advantage of the establishment (Tam 2013: 124). Thus, they work closely with other pro-democracy politicians and activists to translate almost all highly political issues into legal ones through judicial review. Second, as political reform has been curbed and room for promoting fundamental rights in the courts has narrowed in recent years, some progressive lawyers have turned to engaging in more radical activism outside formal legal institutions by participating in direct actions or political campaigns, as illustrated by four silent marches by lawyers, the establishment of the Basic Law Article 45 Concern Group and the Civic Party, the salient role of legal professionals in the OCM, and the emergence of politically oriented groups organised by legal professionals, e.g. the “Progressive Lawyers Group” and “Law Dream.” Third, the mindset of the overall legal professionals in Hong Kong is more complicated and divided under the influence of China. Although the Hong Kong Bar Association (HKBA) remains pro-liberal and outspoken while the Law Society of Hong Kong (LSHK) is still relatively moderate and conservative, as Lee (2017: 5) argued, it seems that “liberal legalism” remains a thread that binds barristers and solicitors together whenever fundamental rights and judicial authority are seen to be at risk. For instance, the HKBA and the LSHK appeared to be unified on some issues, such as the Article 23 legislation in 2003 (Lee 2017: 5) and their response to criticism of judicial independence in Hong Kong.[33] Pro-democratic candidates have continuously won the legal functional constituency seat in LegCo since 1985, even though the majority of the legal practitioners are solicitors (Lee 2017: 5). In 2014, LSHK President Ambrose Lam San-keung was removed for his open praise of the 2014 white paper and the CCP (Lee 2017: 5), and the human rights lawyer Philip Dykes was surprisingly elected Bar Association chairman in 2018.[34] Nevertheless, there is also concern that Beijing’s co-optation of legal professional elites may influence the “common law mind” of Hong Kong lawyers. Some facts seem to support this concern. In recent years, even the outspoken HKBA has been criticised for being much less outspoken since 2006, when Rimsky Yuen became HKBA chairman, and his successors have also kept a distance from political issues.[35] The 2000s saw the emergence of a number of active pro-establishment Hong Kong lawyers (e.g., Lawrence Ma and Wong Kwok Yan Christopher) and lawyers-cum-LegCo members (e.g., Priscilla Leung Mei-fun, Holden Chow Ho-ding, Junius Ho Kwan-yiu) who endorse and promote Beijing’s political and legal perspectives on many controversial issues. Despite the removal of the former LSHK President Ambrose Lam San-Keung in 2014, the 2018 council election of the LSHK showed the mobilising power of the establishment bloc, which made best use of the proxy vote mechanism to help pro-establishment candidates win seats.[36] The campaign reflected the pro-Beijing camp’s concern about “liberal voices getting louder in the traditionally conservative profession.”[37] In July 2018, Melissa Pang, the newly elected LSHK President and a pro-Beijing lawyer, openly commented that the PRC Constitution is the supreme law that should be applied in Hong Kong,[38] echoing a highly controversial speech made by the liaison office’s legal chief, Wang Zhenmin, three days before.[39] Moreover, reformist lawyers risk being marginalised within their ranks as their efforts to run for leadership of professional associations and their cause lawyering are often criticised as attempts to politicise the law, while relatively conservative legal professionals are portrayed by pro-Beijing media as the true defenders of rule of law for clinging to the neutrality of the law.[40] As to the Hong Kong judiciary, its politicisation and independence have become a major concern in recent years, mostly due to the growth of politically sensitive cases and Beijing’s increasing presence in many of those cases through either the formal legal mechanism or high-profile propaganda campaigns. Using the law to postpone politics inevitably brings highly con-tested political disputes to the courts, giving rise to the perception that Hong Kong’s judiciary and law have become politicised.[41] While prominent judges firmly assert the courts’ independence and neutrality, there are dis-agreements among scholars regarding this issue. Some argue that judicial independence is still well maintained and that the real problem is judicial authority (Chen and Lo 2017: 140-1). Another view is that politicisation of the judicial agenda does not necessarily mean politicisation of the courts (Zhu 2017b: 35). This article argues that the Hong Kong judiciary has demonstrated a highly de-politicalised rather than politicalised stance as it persistently emphasises the notion of rule of law with a focus on the rationale of “law and order.” Avoiding taking political morality into account in the adjudication of sensitive cases, the Hong Kong courts have continuously sent a message to the public, through top judges’ speeches or judgments of high-profile cases, that the “image of the rule of law was (…) complying with existing legal order and the well-functioning of Hong Kong society” (Ho 2017: 142), while other substantial values and agendas, such as promoting democracy and political reform, should not be debated or considered in the judicial arena.[42] In sharp contrast to the Taiwan courts’ acquittal decisions in the trials of Sunflower Movement participants, the Hong Kong courts have generally demonstrated a more restrictive attitude toward civil disobedience and a stronger emphasis on the existing legal order. While the Taiwanese court regarded the cause of the Sunflower Movement as a “public interest” and took it into account in making its decision, the Hong Kong courts, in most of the OCM and Mong Kok riot-related cases, explicitly ruled that the court’s decision should exclude any political factors, including the defendants’ political motivation.[43] In trying politically sensitive cases, being caught in the middle of the central government’s hostility toward democracy and local civil society’s demand for democracy, Hong Kong courts have tried to strike a delicate balance between, on the one hand, protecting fundamental rights (which has been increasingly intertwined with pro-democracy and localist activism), and on the other hand, upholding the central government’s authority without antagonising Beijing. Since the 1999 Lau Kong Yung case,[44] the Hong Kong courts have changed their previous opinion that the courts have the power to review NPCSC interpretations, but instead have held that the NPCSC enjoys freestanding power to interpret the Basic Law. The courts maintained a highly deferential attitude toward the NPCSC in subsequent cases, thus avoiding direct confrontation with the central authorities as they did in 1999.[45] In cases that touch upon the sovereignty issue and the central authorities’ sensitive spots, such as the 1998 desecration of the national flag case,[46] the 2016 oath-taking cases,[47] the 2011 Congo case,[48] and the 2018 joint rail checkpoint case,[49] the court’s rulings have firmly stressed and upheld the “one country” principle and existing constitutional order, hailed by some mainland scholars as the growth of national consciousness among Hong Kong judges (Hao 2013: 83-91). It is doubtful whether there has been a perceptible increase in so-called national consciousness, since even before the first NPCSC interpretation was issued in 1999, the court had already shown great respect for the “one country” principle under the new constitutional order immediately after the handover in cases such as the 1997 Ma Wai Kwan case and the 1998 desecration of the national flag case.[50] It is therefore hard to say that the transfer of sovereignty has shaped the position of Hong Kong courts. It is probably the inherent conservative dimension of the common law and the judiciary that determines the pro-establishment inclination of the courts in a semi-democracy under the shadow of authoritarianism. Despite its deferential attitude toward the NPCSC’s authority, the Hong Kong judiciary still plays a crucial role in protecting fundamental rights and checking the power of the HKSAR government in many politically sensitive cases where the sovereignty issue is not the focal point, e.g., the 2005 Fa Lungong case[51] and the “seven policemen case.” Compared with their deferential attitude toward the central authorities, the courts demonstrated a robust stance in exercising judicial review power over the HKSAR executive and legislative authorities, as shown in the oath-taking cases. The emphasis on the apolitical nature of the courts is a necessary technical apparatus for the Hong Kong courts to resist real or potential interference from Beijing and to strike a delicate balance between pressure from the central authorities and a strong grassroots demand for democracy. Nevertheless, the de-politicisation strategy has its downside. To a certain extent, the courts have unwittingly collaborated with the central government’s “legalisation without democratisation” strategy in many politically sensitive cases, particularly the 2016 oath-taking cases, the jailing of land protesters in 2017,[52] and the OCM – and Mong Kok riot-related cases. The harsh punishment imposed by the law and the emphasis on maintaining social stability have alienated pro-democratic activists and deterred like-minded citizens from joining social campaigns (Ho 2017: 142). Most defendants who were involved in civil disobedience and massive protests were very cooperative and demonstrated a deferential attitude toward the law in trials, in sharp contrast to many mainland human rights activists and lawyers who have been vocally critical of law and have directly confronted judicial authorities in the courts. Compared to an undeveloped legal system, an advanced rule-of-law system in an undemocratic context seems to be a more efficient instrument in containing social activism and political dissidence. The emphasis on the procedural dimension of classic liberalism can cater to tyrannical regimes. Liberalism and rule of law can be construed in a restrictive rather than progressive sense, as is the case in Hong Kong (Lee 2017: 6). A similar judicial conservativism could also be seen in colonial Hong Kong and other hybrid regimes such as Singapore. The judiciary alone, even if highly developed, can hardly resist the pressure of authoritarianism and shoulder the burden of promoting democracy in an undemocratic context. Hong Kong is simply no exception.

Conclusion: Rule of law under authoritarianism

“Legalisation without (full) democratisation” has been the core pillar of Beijing’s overall legal strategy for governing Hong Kong. Firmly entrenched since the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, it has remained the cornerstone of its governing strategy over the past decades. The official legal discourse has evolved from emphasising the notion of “executive-led government” to “plenary power to govern Hong Kong” and “the application of the PRC Constitution to Hong Kong.” In practice, Beijing has incrementally redefined some provisions and concepts related to the Basic Law to serve its governing purpose.[53] In the post-OCM period, the central government has further stressed the application of the PRC Constitution in Hong Kong in response to the rising secessionist clamour and to serve the integration strategy. Although its power to interfere with the operation of Hong Kong’s rule of law is still largely circumscribed by the Basic Law, the central government never hesitates to take a tough approach in crucial issues that touch on its core interests. On the surface, the “legalisation without democratisation” principle is quite efficient for the time being. The central authorities have efficiently stressed the rhetorical notion of the rule of law and have skilfully used limited but crucial legal channels, particularly NPCSC interpretations and decisions, to prevent dramatic political reform and to suffocate separatist activism in Hong Kong. However, the “legalisation without democratisation” and “integration” strategies largely conflict with the demands of a significant portion of Hong Kong’s civil society for full democracy, a high degree of autonomy, maintenance of a liberal rule of law tradition, and anti-mainlandisation. Such measures also create a gap that generates continuing momentum for pro-democracy campaigning, give rise to suspicions over the role of law in advancing democracy, and radicalise a portion of the pro-democracy campaign into pro-independence activism. The tension brought by “legalisation without democratisation” will continue in the future, and further enhancement of legality will not resolve the inherent tensions. It is difficult for Beijing to copy the model of British rule over colonial Hong Kong, as Kuan precisely foresaw in 1997: the “foundation for the past practice in governing through consultation, i.e., elite solidarity and lack of mass mobilisation, (…) no longer exists” after the handover (Kuan 1998: 1445). Influence by legalisation without democratisation brings a worrying trend of rising authoritarian legalism in Hong Kong, as local authorities have increasingly utilised legal means to crack down on separatism and have con-strained political space for other oppositional forces, catering to the central government’s agenda. Those legal measures have posed an evident and potential threat to fundamental rights and freedom. Facing pressures from both the central authorities and bottom-up demand for democracy, the Hong Kong judiciary has adopted a depoliticisation stance and has demonstrated an inclination to emphasise the existing legal order while excluding any political factors outside the courts. On the one hand, this is conducive to resisting erosion by the central power, and the court has done well so far in defending the liberal values of Hong Kong’s common law (Chan 2018: 373). On the other hand, it has narrowed the space for legal and political mobilisation that directly challenges the central authorities, to the disappointment of the social movement sector and some progressive legal professionals, who have begun to doubt the rule of law under the influence of rising authoritarian legality and thus have turned to more politilised activism outside the courts. In the contemporary world, there is perhaps no other legal complex similar to that of the HKSAR: a highly developed common law system that exists within an authoritarian civil law system with so-called socialist characteristics. The rule of law issue in Hong Kong is inevitably intertwined with that in China. Under the shadow of authoritarianism, political and rule of law advocates in Hong Kong have begun to share the same fate as their mainland counterparts, who have struggled between the thin and thick versions of the law. They have confronted the same typical “Chinese characteristics” of socialist rule of law, such as the “equation of law and power” (Pils 2017: 31) and “employing arguments that seem convenient in the moment” (ibid.: 6). The law may provide both opportunities and obstacles for the causes of both groups. Thus, to democratise the law, or to neutralise the law, that is the question.

Han Zhu is Assistant Research Officer at the Centre for Chinese Law, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong (zhuhanhk@hku.hk).

Manuscript received on 29 August 2018. Accepted on 18 January 2019.

[1] Also see Gary Cheung, “June 4, 1989 Events in China Still Have a Profound Effect on Hong Kong’s Political Scene,” South China Morning Post, 26 May 2014, http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1519713/june-4-1989-events-china-still-have-profound-effect-hong-kongs (accessed on 11 July 2018). [2] Ibid. [3] “全面管治權:從委婉到直接,是強硬是積極 ?” (Quanmian guanzhiquan: cong weiwan dao zhijie, shi qiangying shi jiji?, From implicit to blatant expression of the plenary power to govern: is it a sign of turning tough or positive?), 23 October 2017, https://www.hk01.com/社會新聞 /127752/十九大解讀-全面管治權-從委婉到直接-是強硬是積極 (accessed on 1 January 2019). [4] Zhang Xiaoming 張曉明, “豐富‘一國兩制’實踐” (Fengfu ‘yiguo liangzhi’ shijian, Enrich the practice of ‘one country, two systems’), Wen Wei Po, 22 November 2012, A17. [5] “The Practice of the ‘One Country, Two Systems‘ Policy in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region”, The State Council of the PRC, 10 June 2014, http://www.fmcoprc.gov.hk/eng/xwdt/gsxw/t1164057.htm (accessed on 11 July 2018). [6] “Decision of the NPCSC on Issues Relating to the Methods for Selecting the Chief Executive of the HKSAR and for Forming the Legislative Council of the HKSAR in the Year 2012 and on Issues Relating to Universal Suffrage”, 29 December 2007, http://www.npc.gov.cn/englishnpc/Law/2009-02/26/content_1473392.htm (accessed on 25 January 2019). [7] Benny Tai, “公民抗命的最大殺傷力武器” (Gongmin kangming de zuida shashangli wuqi, The most destructive weapon of civil disobedience), Hong Kong Economic Journal, 16 January 2013, http://oclp.hk/index.php?route=occupy/article_detail&article_id=23 (accessed on 25 January 2019). [8] “The Practice of the ‘One Country, Two Systems‘ Policy in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region”, The State Council of the PRC, 10 June 2014, http://www.fmcoprc.gov.hk/eng/xwdt/gsxw/t1164057.htm (accessed on 11 July 2018). [9] The full text of the report is available at http://news.ifeng.com/a/20171027/52825234_0.shtml (accessed on 11 July 2018). [10] “Decision of the NPCSC on Issues Relating to the Selection of the Chief Executive of the HKSAR by Universal Suffrage and on the Method for Forming the Legislative Council of the HKSAR in the Year 2016”, 31 August 2014, http://www.2017.gov.hk/filemanager/template/en/doc/ 20140831b.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2019). [11] See “Joint Statement of The Hong Kong Bar Association and The Law Society of Hong Kong in Response to Criticisms of Judicial Independence in Hong Kong,” 18 August 2017, https://www.hkba.org/events-publication/press-releases-coverage (accessed on 11 July 2018). [12] Eddie Lee, “Beijing Throws the Book at Hong Kong’s Foreign Judges,” SCMP, 9 March 2017, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-crime/article/2077521/experts-line-throw-book-hong-kongs-foreign-judges (accessed on 11 July 2018). [13] “Term of Non-permanent CFA Judges Extended,” Press release of the Government of the HKSAR, 21 February 2018, http://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201802/21/P2018022100260.htm?font-Size=1 (accessed on 12 July 2018). [14] Joyce Ng et al., “Legislative Council Disqualifications Shift the Balance of Power in Hong Kong,” SCMP, 14 July 2017, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2102733/legisla-tive-council-disqualifications-shift-balance-power (accessed on 12 July 2018). [15] CACV 224/2016, 15 November, 2016, paras 19, 40(1) and 52. [16] For the list of disqualified pro-independence candidates, see Kwong (2018). [17] Jeffie Lam and Tom Cheung, “Hong Kong separatist political party given 21-day ultimatum to contest unprecedented ban,” SCMP, 17 July 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/pol-itics/article/2155566/hong-kong-separatist-political-party-faces-landmark (accessed on 19 July 2018). [18] Jasmine Siu, “Mong Kok riot: Youngest of 10 defendants given heaviest sentence for ‘wanton use of violence that took advantage of tolerant police’,” SCMP, 1 June 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/hong-kong-law-and-crime/article/2148726/mong-kok-riot-youngest-10-de-fendants-given (accessed on 19 July 2018). [19] “Decision of the NPC on the Basic Law of the HKSAR of the PRC,” 4 April 1990, https://www.eleg-islation.gov.hk/hk/A104!en.assist.pdf?FROMCAPINDEX=Y (accessed on 12 July 2018). [20] Full text of all previous reports of the General Secretary of the CCP to the CCP National Congress are available at http://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/64162/64168/index.html (access on 12 July 2018). [21] Bruce Lui, “憲法自動適用香港?讓官方報告來踢爆” (Xianfa zidong shiyong xianggang? Rang guanfang baogao lai tibao, Constitution applies to Hong Kong automatically? Let official docu-ments say), Ming Pao, 18 July 2018, A27. [22] Ibid. [23] Ng Kang-chung and Sum Lok-kei, “Qiao Xiaoyang’s mission to ‘promote and popularise’ Chinese constitution in Hong Kong,” SCMP, 20 April 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/pol-itics/article/2142503/qiao-xiaoyangs-mission-promote-and-popularise-chinese (accessed on 12 July 2018); Sum Lok-kei, “Liaison office legal chief tells Hong Kong: Basic Law is not your consti-tution,” SCMP, 15 July 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2155297/liaison-office-legal-chief-tells-hong-kong-basic-law-not (accessed on 20 July 2018). [24] Tony Cheung, “People who chant ‘end one-party dictatorship’ slogan are breaking law and should be banned from seeking political office, says Wang Guangya,” SCMP, 25 April 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2143260/people-who-chant-end-one-party-dictatorship-slogan-are (accessed on 24 July 2018). [25] Kris Cheng, “45 Civil Groups Decry Hong Kong’s ‘Deteriorating Rule of Law and Human Rights En-vironment’ in UN Submission,” Hong Kong Free Press, 10 April 2018, https://www.hongkongfp.com/2018/04/10/45-civil-groups-decry-hong-kongs-deteriorating-rule-law-human rights-environment-un-submission/ (accessed on 12 July 2018). [26] Hong Kong’s economic freedom scores ranked No. 1 in the 2018 index, and Rule of Law is one of the four sub-indicators of the Index. See https://www.heritage.org/index/ranking. [27] For a detailed elaboration on the four rule of law indicators, see Versteeg and Ginsburg (2017). [28] “法夢達人黃啟暘 別讓法律被時代框死” (Fameng daren Huang Qiyang: Bie rang falü bei shidai kuangsi, Wong Kai-yeung: A key member of Law Dream: Don’t let the law be shaped by the times), Ming Pao, 10 December 2017, https://news.mingpao.com/pns/dailynews/web_tc/article/20171210/s00005/1512840873614 (accessed on 25 January 2019). [29] “The underlying goal of the principles and policies adopted by the central government concerning Hong Kong and Macau is to uphold China’s sovereignty, security and development interests and maintain long-term prosperity and stability of the two regions.” See the “Report of Hu Jintao to the 18th CPC National Congress,” 8 November 2012, http://www.china.org.cn/china/18th_cpc_congress/2012-11/16/content_27137540.htm (accessed on 12 July 2018). [30] After the five booksellers case, Hong Kong’s independent bookstores and publications have suf-fered. In particular, the publication of politically sensitive books has almost completely disap-peared. See Chen Qian-er 陳倩兒 et al., “銅鑼灣書店一年後,禁書讀者、作者與出版商之死” (Tongluowan shudian yinian hou, jinshu duzhe, zuozhe yu chubanshang zhisi, One year after the Causeway bookstore event, the death of readers, authors, and publishers of banned books), Initium Media, 30 December 2016, https://theinitium.com/article/20161230-hongkong-politicalbooksin-hongkong/ (accessed on 12 July 2018). [31] Ilaria Maria Sala, “Independent publishing in Hong Kong – a once-flourishing industry annihilated by fear,” HKFP, 17 February 2018, https://www.hongkongfp.com/2018/02/17/independent-pub-lishing-hong-kong-flourishing-industry-annihilated-fear (accessed on 25 July 2018); see also Lee (2018). [32] Only a handful of scholars, such as Waikeung Tam, Man Yee Karen Lee, Liu Sida, and Hsu Ching-fang, have done pioneering empirical studies on this matter. [33] E.g., see “Joint Statement of The Hong Kong Bar Association and The Law Society of Hong Kong in Response to Criticisms of Judicial Independence in Hong Kong,” 18 August 2017, https://www.hkba.org/events-publication/press-releases-coverage (accessed on 11 July 2018). [34] Ibid. [35] Wu Zhuo’an 吳倬安, “戴啟思當選公會主席 北京憂溝通之路停滯不前” (Daiqisi dangxuan gonghui zhuxi, beijing you goutong zhilu tingzhi buqian, Philip Dykes elected head of HKBA, Beijing worries about stagnation of relationship with the bar), HK01.com, https://www.hk01.com/社會新聞/151054/戴啟思當選公會主席-北京憂溝通之路停滯不前 (accessed on 14 July 2018). [36] Kimmy Chung, “Conservative lawyers’ good showing in Hong Kong Law Society election driven by proxy votes,” SCMP, 1 June 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/hong-kong-law-and-crime/article/2148872/conservative-lawyers-good-showing-hong-kong (accessed on 11 February 2019). [37] Ibid. [38] “Law Society Head says Constitution Supreme,” The Standard, 17 July 2018, http://www.thes-tandard.com.hk/breaking-news.php?id=110563&sid=4 (accessed on 26 July 2018). [39] Sum Lok-kei, “Liaison office legal chief tells Hong Kong: Basic Law is not your constitution,” SCMP, 15 July 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2155297/liaison-office-legal-chief-tells-hong-kong-basic-law-not (accessed on 26 July 2018). [40] Tu Haiming 屠海鳴, “香港律師會勿成為泛政治化環境的犧牲品” (Xianggang Lüshihui wu chengwei fan zhengzhihua huanjing de xishengpin, Hong Kong Law Society should not fall victim to the pan-politicalisation environment), Ta Kung Pao, 1 June 2018, A5. [41] Zheng Yongnian 郑永年, “‘占中’判決与香港前途” (“Zhanzhong” panjue yu xianggang qiantu, Occupy central-related judgments and Hong Kong’s future), IPP Review, 12 June 2017, http://www.sohu.com/a/126626174_550967 (accessed on 11 February 2019). [42] Jasmine Siu, “Mong Kok riot: Youngest of 10 defendants given heaviest sentence for ‘wanton use of violence that took advantage of tolerant police’,” SCMP, 1 June 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/hong-kong-law-and-crime/article/2148726/mong-kok-riot-youngest-10-de-fendants-given (accessed on 16 July 2018). [43] HKSAR v. Mo Jiatao and 8 Others [2018 HKDC 225], para. 12; Alvin Lum, “Ousted lawmakers Bag-gio Leung and Yau Wai-ching jailed for four weeks for storming Hong Kong Legislative Council meeting,” SCMP, 4 June 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2149103/ousted-lawmakers-baggio-leung-and-yau-wai-ching-jailed-four (accessed on 16 July 2018). [44] Lau Kong Yung v. Director of Immigration [1999] 3 HKLRD 778. [45] Ng Ka Ling v. Director of Immigration [1999] 1 HKLRD 315. [46] HKSAR v. Ng Kung-siu and Lee Kin Yun [1999] FACC 4/1999. [47] Chief Executive of HKSAR & Secretary for Justice v. Leung Chung-hang, Yau Wai-ching, and Pres-ident of the Legislative Council (HCAL 185/2016 & HCMP 2819/2016); Chief Executive of HKSAR & Secretary for Justice v. President of the Legislative Council, Nathan Law Kwun Chung, and others (HCAL 223-226/2016, HCMP3378/2016). [48] Democratic Republic of the Congo v. FG Hemisphere Associates LLC [2011] 4 HKC 151. [49] [2018] HKCFI 2657. [50] HKSAR v. Ng Kung Siu and Lee Kin Yun [1999] 2 HKCFAR 442. [51] Yueng May Wan v. HKSAR [2005] 2 HKLRK 212. [52] “Hong Kong jails lands protesters after they served their sentences,” RFA, 15 August 2017, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/hong-kong-jails-land-protesters-after-they-served-their-sentences-08152017102708.html (accessed on 27 July 2018). [53] E.g., the procedures for approving Hong Kong’s political reform (Appendix 1 and 2), and the scope and procedures of NPCSC interpretations (Article 158).

References