BOOK REVIEWS

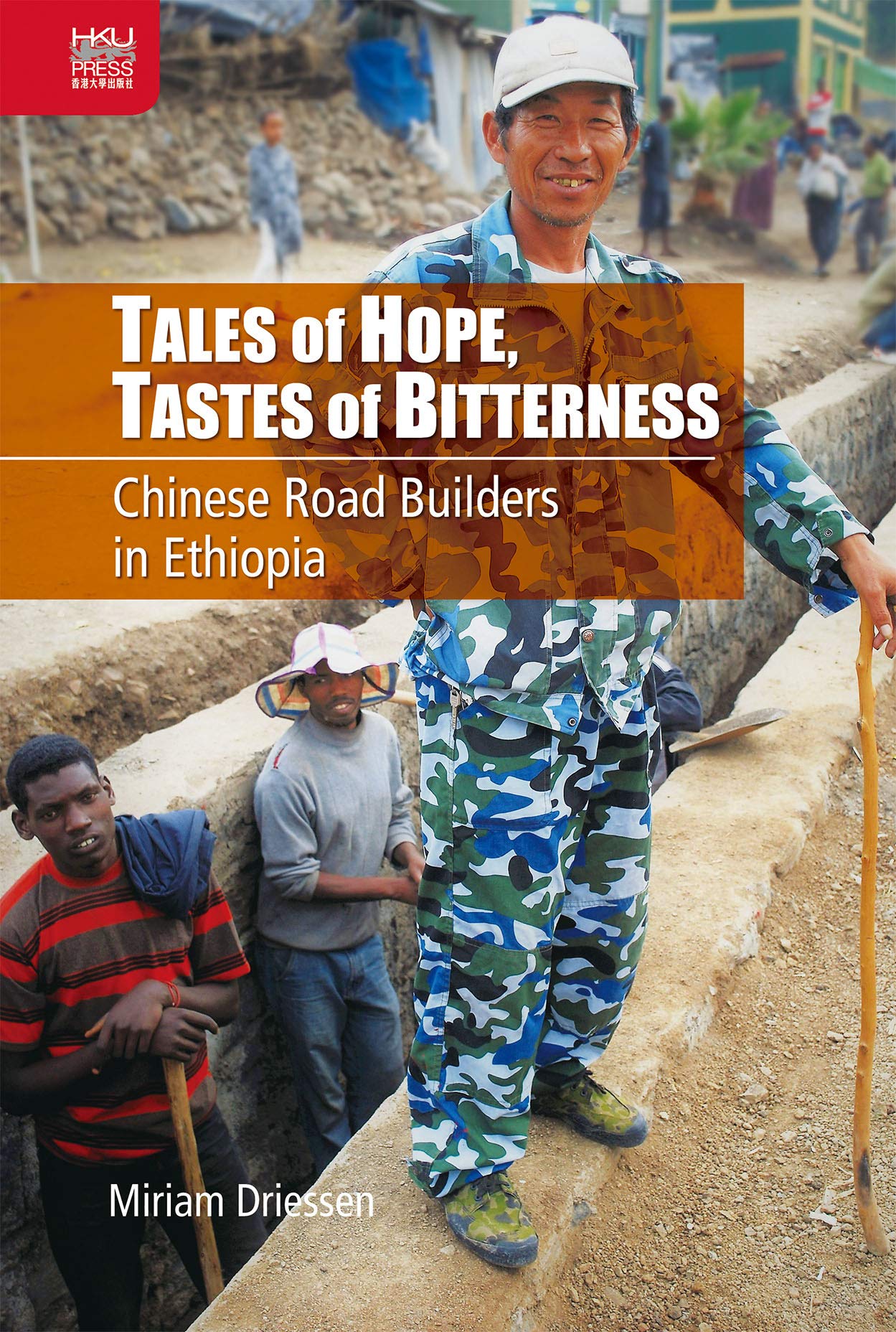

DRIESSEN, Miriam. 2019. Tales of Hope, Tastes of Bitterness: Chinese Road Builders in Ethiopia. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Miriam Driessen’s Tales of Hope, Tastes of Bitterness: Chinese Road Builders in Ethiopia offers a nuanced ethnography of the actors involved in a road construction project in Ethiopia. The project was funded by the Ethiopian government and the European Union and spearheaded by a Chinese contractor. The Chinese contractor relied on six Chinese companies and a handful of Ethiopian companies to carry out the road works. A total of 125 Chinese workers and 700-800 Ethiopian workers were engaged in the project at its peak in 2012. The vast number of people involved in the project plus the physical distance of 100-kilometers that had to be covered certainly make for an unusual site to conduct ethnographic fieldwork. Driessen successfully explored it by devising innovative research strategies. During ten months of field research in 2011 and 2012, Driessen moved along the road construction, interviewing and observing Chinese and Ethiopian workers as well as local villagers and representatives of local institutions. Driessen thereby provides a unique window into the everyday lives, interactions, and challenges of Chinese road builders and their Ethiopian counterparts.

In her book, Driessen analyses situations of contact in which Chinese and Ethiopian workers meet and contest with each other in highly asymmetric relations of power. After a brief introduction, Driessen presents the motivations and visions of Chinese migrants (Chapter 1). They leave China to escape their precarious situation with the hope of securing a better life in China in the future. While Chinese workers in Ethiopia share similar motivations and hopes, Driessen shows that they are internally divided (Chapter 2). Salaries and other benefits (daiyu 待遇) vary greatly among private, state-owned, or public-private Chinese companies. Within the companies, workers are further divided by age, work experience, class, and hierarchical position. Chinese workers used the “speaking bitterness” narrative (suku 訴苦) as a way to talk about their experience in Ethiopia (Chapter 7). In their stories, workers pitied themselves for all the things they had to put up with, while also celebrating their individual and collective toughness and perseverance in the face of difficulties. Taken together, these chapters provide a nuanced picture of Chinese migrants and highlight that they were often disappointed by their stay in Ethiopia.

Although company managers would like to preserve a distinct Chinese purity by discouraging sexual intimacy between Chinese men and Ethiopian women, the everyday reality on the construction site is quite different (Chapter 3). The many instances of sexual intimacy sparked fierce discussions among Chinese managers on the notions of race and racial difference. They also challenged the authority and racial disparities in employment conditions set up by the Chinese management. Chinese managers had an even harder time trying to fashion Ethiopian workers into industrious laborers (Chapter 4). Ethiopian workers could not be convinced of the need for self-development because they could reap few personal benefits. The erratic disciplinary methods of Chinese managers to make Ethiopian workers compliant and diligent often backfired (Chapter 5). Through small acts of everyday defiance and subtle transgressions of company rules, Ethiopian workers challenged the authority of their Chinese bosses. The managers’ authority was further undermined when Ethiopian workers and villagers sued Chinese companies in local courts (Chapter 6). With the help of local courts, Ethiopian workers improved their employment conditions. Chinese managers felt abandoned by the local authorities because they sided with Ethiopian workers. These chapters show that Ethiopian workers exerted considerable agency – often setting the rules of interaction.

In some parts of the book, a few extra details on specific informants and situations could have enhanced the explanatory power of Driessen’s already superb ethnographic material. For instance, at the opening of Chapter 6, I was curious to know why exactly Li Deye remained silent on the way back from court and what happened after he disappeared into his room (p. 132). I was likewise left wondering why an old man named Hamid Mengesha was chosen as the authority to speak on the political influence of Chinese road workers in Ethiopia (Chapter 8). Similarly, textual material was sometimes not contextualised. For example, Driessen takes a discussion on the Zhihu 知乎 website about two pictures – one of a Chinese man, the other of an African woman – to show Chinese netizens’ preoccupation with skin colour (Chapter 4). As a reader, I would have liked to know why she chose that particular discussion thread and how it is similar to or different from other online discussions.

Driessen draws on self-development literature to discuss differences in workers’ discipline and outlook on life. Certainly, self-development is a dominant theme in post-Mao China. Studies on factory workers (Pun 2005) and maids (Yan 2008) document that Chinese rural migrants believe that they have to transform themselves into docile workers in order to succeed. Driessen argues that Ethiopian workers refuse to become docile workers, much to the surprise of their Chinese managers and co-workers. However, incidents such as Chinese workers killing themselves to draw attention to their dire work conditions in factories in South China suggest that the outlook of Chinese and Ethiopian workers is more similar than Driessen’s discussion suggests. Chinese workers, like their Ethiopian counterparts, realise that self-development and being a docile worker serves first and foremost the interests of the state and the factories. Hence, they use drastic tactics to negotiate better pay and working conditions. I would argue that this even applies to the construction industry in China. While construction workers in the 1990s had little security for life and pay, they also managed to improve safety regulations and labour laws by frequent protests. This suggests that even in China, the submissive, docile worker is becoming an abstract ideal rather than a lived reality. Chinese managers in Ethiopia might try to uphold this ideal, but it is certainly not the status-quo in China any longer.

In her book, Driessen skilfully combines an analysis of her rich ethnographic material with a discussion on labour relations, migration, race, and globalisation. Her engaging style makes it easy to follow her argument. The book is not just an addition to existing studies on African-Chinese relations. Rather, it is an inspiring example of how China-Africa research could move out of a niche dominated by international relations and macro-economic theory in order to engage with wider debates in anthropology, global history, and Chinese studies. As such, it is a must-read for anthropologists and China-Africa scholars and a useful source for graduate and undergraduate courses.

Miriam Driessen’s Tales of Hope, Tastes of Bitterness: Chinese Road Builders in Ethiopia offers a nuanced ethnography of the actors involved in a road construction project in Ethiopia. The project was funded by the Ethiopian government and the European Union and spearheaded by a Chinese contractor. The Chinese contractor relied on six Chinese companies and a handful of Ethiopian companies to carry out the road works. A total of 125 Chinese workers and 700-800 Ethiopian workers were engaged in the project at its peak in 2012. The vast number of people involved in the project plus the physical distance of 100-kilometers that had to be covered certainly make for an unusual site to conduct ethnographic fieldwork. Driessen successfully explored it by devising innovative research strategies. During ten months of field research in 2011 and 2012, Driessen moved along the road construction, interviewing and observing Chinese and Ethiopian workers as well as local villagers and representatives of local institutions. Driessen thereby provides a unique window into the everyday lives, interactions, and challenges of Chinese road builders and their Ethiopian counterparts.

In her book, Driessen analyses situations of contact in which Chinese and Ethiopian workers meet and contest with each other in highly asymmetric relations of power. After a brief introduction, Driessen presents the motivations and visions of Chinese migrants (Chapter 1). They leave China to escape their precarious situation with the hope of securing a better life in China in the future. While Chinese workers in Ethiopia share similar motivations and hopes, Driessen shows that they are internally divided (Chapter 2). Salaries and other benefits (daiyu 待遇) vary greatly among private, state-owned, or public-private Chinese companies. Within the companies, workers are further divided by age, work experience, class, and hierarchical position. Chinese workers used the “speaking bitterness” narrative (suku 訴苦) as a way to talk about their experience in Ethiopia (Chapter 7). In their stories, workers pitied themselves for all the things they had to put up with, while also celebrating their individual and collective toughness and perseverance in the face of difficulties. Taken together, these chapters provide a nuanced picture of Chinese migrants and highlight that they were often disappointed by their stay in Ethiopia.

Although company managers would like to preserve a distinct Chinese purity by discouraging sexual intimacy between Chinese men and Ethiopian women, the everyday reality on the construction site is quite different (Chapter 3). The many instances of sexual intimacy sparked fierce discussions among Chinese managers on the notions of race and racial difference. They also challenged the authority and racial disparities in employment conditions set up by the Chinese management. Chinese managers had an even harder time trying to fashion Ethiopian workers into industrious laborers (Chapter 4). Ethiopian workers could not be convinced of the need for self-development because they could reap few personal benefits. The erratic disciplinary methods of Chinese managers to make Ethiopian workers compliant and diligent often backfired (Chapter 5). Through small acts of everyday defiance and subtle transgressions of company rules, Ethiopian workers challenged the authority of their Chinese bosses. The managers’ authority was further undermined when Ethiopian workers and villagers sued Chinese companies in local courts (Chapter 6). With the help of local courts, Ethiopian workers improved their employment conditions. Chinese managers felt abandoned by the local authorities because they sided with Ethiopian workers. These chapters show that Ethiopian workers exerted considerable agency – often setting the rules of interaction.

In some parts of the book, a few extra details on specific informants and situations could have enhanced the explanatory power of Driessen’s already superb ethnographic material. For instance, at the opening of Chapter 6, I was curious to know why exactly Li Deye remained silent on the way back from court and what happened after he disappeared into his room (p. 132). I was likewise left wondering why an old man named Hamid Mengesha was chosen as the authority to speak on the political influence of Chinese road workers in Ethiopia (Chapter 8). Similarly, textual material was sometimes not contextualised. For example, Driessen takes a discussion on the Zhihu 知乎 website about two pictures – one of a Chinese man, the other of an African woman – to show Chinese netizens’ preoccupation with skin colour (Chapter 4). As a reader, I would have liked to know why she chose that particular discussion thread and how it is similar to or different from other online discussions.

Driessen draws on self-development literature to discuss differences in workers’ discipline and outlook on life. Certainly, self-development is a dominant theme in post-Mao China. Studies on factory workers (Pun 2005) and maids (Yan 2008) document that Chinese rural migrants believe that they have to transform themselves into docile workers in order to succeed. Driessen argues that Ethiopian workers refuse to become docile workers, much to the surprise of their Chinese managers and co-workers. However, incidents such as Chinese workers killing themselves to draw attention to their dire work conditions in factories in South China suggest that the outlook of Chinese and Ethiopian workers is more similar than Driessen’s discussion suggests. Chinese workers, like their Ethiopian counterparts, realise that self-development and being a docile worker serves first and foremost the interests of the state and the factories. Hence, they use drastic tactics to negotiate better pay and working conditions. I would argue that this even applies to the construction industry in China. While construction workers in the 1990s had little security for life and pay, they also managed to improve safety regulations and labour laws by frequent protests. This suggests that even in China, the submissive, docile worker is becoming an abstract ideal rather than a lived reality. Chinese managers in Ethiopia might try to uphold this ideal, but it is certainly not the status-quo in China any longer.

In her book, Driessen skilfully combines an analysis of her rich ethnographic material with a discussion on labour relations, migration, race, and globalisation. Her engaging style makes it easy to follow her argument. The book is not just an addition to existing studies on African-Chinese relations. Rather, it is an inspiring example of how China-Africa research could move out of a niche dominated by international relations and macro-economic theory in order to engage with wider debates in anthropology, global history, and Chinese studies. As such, it is a must-read for anthropologists and China-Africa scholars and a useful source for graduate and undergraduate courses.