BOOK REVIEWS

Platform Labour and Contingent Agency in China

Introduction

The question of how digital technologies have changed the employment structure in China leads to no easy answer. Some scholars see digital workers as a new class in the making, with solidarity and empowered subjectivity (Smith and Pun 2018), while others connect Chinese workers’ experience to the global trend of precarity and argue for a careful assessment of workers’ empowerment against political and institutional changes (Lee 2016). This literature provides critical and valuable understandings about labour agency and worker empowerment actions in general. In the debate on Chinese worker’s empowerment or class formation, however, there is limited systemic documentation and examination of workers’ exercise of agency. Complementing the macro approach toward the collective movement or institutional changes, we adopt a micro lens in this article to address the question of agency by examining workers’ lived experiences, struggles, and survival tactics in the shadow of platform capitalism.

There has been a rapid expansion of the labour force in the Chinese digital economy during the last decade, and the trend is likely to continue. It is estimated that more than 200 million people will be working in China’s digital economy by 2020.[1] Platform-mediated food-delivery service provision has become one of the fastest growing sectors for various employment types (Sun 2019). Although there is no official employment data about the food-delivery sector, the number of riders at Meituan and Ele.me, the two market leaders in China, exceeded 6 million in May 2020.[2] The emerging platform-mediated logistical chain in the case of food-delivery service gives rise to intricate and networked relations among the platforms, intermediaries, restaurants, and workers, which to a large extent introduce new factors to shape workers’ subjectivities, identities, and the way in which they exercise and perform their agency.

In line with growing efforts to examine workers’ resistance and collective actions in the platform economy (Chen 2018; Cant 2019), we intend to explore food-delivery workers’ agentic performance. We not only document the localised and organised forms of workers’ resistance and activism, but also reflect on the reconfiguration of labour agency and workers’ subjectivity against the changing landscape of platform labour politics in China. We ask three questions: 1) How do food-delivery workers practice agency in their work? 2) How can their practice inform the current understandings of worker agency under platform capitalism? 3) What are the implications of this study for labour politics in contemporary China?

Addressing these questions, this article examines workers’ agency in the multi-layered labour regimes that are characterised by hypercapitalism (Graham 2000), algorithmic control of the labour process, and an eroding social foundation for solidarity and community-building among workers. We suggest a concept of “contingent agency” to capture Chinese gig workers’ expedient and dynamic mobilisation of individual and social resources and technologies to survive and thrive in the platform economy. The term contingent agency describes how food-delivery workers carve spaces for economic gains at the individual and small-scale collective levels while combating an increasingly unbalanced power that tilts toward the platform companies. As with all other social and cultural subjects, worker’s exercise of agency is self-evident (Ortner 2006), yet under-explored in, and outnumbered by, the mounting studies on the technological power of the platforms (e.g. Van Dijck et al. 2018). Far from a static possession, agency is almost always contingent on a number of structural and circumstantial factors. Nonetheless, by drawing attention to workers’ agency demonstrated through its tensions with a number of factors ranging from capitalistic logic and the algorithmic control of the labour process to the cultural tradition to establish mutually reciprocal social relations, we argue that the formation of contingent agency of platform workers in China is indicative of the new challenges and possibilities for the working subjects in platform capitalism.

Literature review

Situating agency in the digital workplace

Agency is an underpinning theme and analytical perspective in many philosophical and social theories (e.g. Giddens 1991). Scholars have examined different meanings and dimensions of agency, human agentic practices, and the relations between agency and social structures (Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Giddens 1991; Taylor 1985). According to Emirbayer and Mische (1998), agency is “a temporally embedded process of social engagement” (ibid.: 962), which is closely related to people’s construction of selfhood, will, freedom, creativity, and subjectivity.

In labour studies, agency serves as a prominent perspective to investigate workers’ self-consciousness and collective capability of organisation to negotiate with employers or advance their rights in the face of state power and global capitalism. Although agency remains a key concept in labour studies, little literature has directly used the term “agency.” Instead, it is often replaced with concepts such as “collectivism” (Lucio and Stewart 1997), “empowerment” (Vidal 2007), “resistance” (Bieler and Lee 2018), and “activism” (Zajak et al. 2017). As it is argued, agency is a significant mediator between social structure and social action (Emirbayer and Mische 1998). On the one hand, social structures such as class, habit, rules, systems, and other contextual elements may exert effects on people’s agentic consciousness. On the other hand, this agency shapes people’s social actions in different ways. Ortner (2006: 107) cautions against the deterministic tendency of the structuralists and suggests that subjectivity embodies the dialectic relationship between “the ensemble of modes of” perception, affect, and thought of a subject and “the cultural and social formations that shape, organize, and provoke those modes of affect [and] thought” of the acting subjects.

The booming digital economy and the widespread use of the Internet and mobile phones have inspired growing scholarly interest in how workers use digital technologies and how they respond to the digitally-mediated work environment. For example, Qiu (2016) depicts how the working class uses social media to create “worker-generated contents (WGCs)” in order to “inform, mobilize and counter-attack” in the labour struggles (ibid.: 627). Specifically related to the platform economy, Chen (2018) examines how taxi drivers in China fight against the ride-hailing platform through protests and algorithmic activism. Zhang documents how small business owners utilised social media to mobilise against the e-commerce platform Taobao’s “bloodsucking” (Zhang 2020: 128) exploitation. On the other hand, scholars also point to a further fragmentation and informalisation of the labour force in the digital economy, resulting in sustained erosion of workers’ structural power (Dyer-Witheford 2015; Lazar and Sanchez 2019). Fieseler, Bucher, and Hoffmann (2017: 27) argue that “work-based identity, cohesion and pride” is weakened significantly in crowdsourcing platforms such as Amazon Mechanical Turk, which undermines workers’ collective bargaining power.

It is tempting to explain the contradictory findings about workers’ resistance and activism in the digital economy as an “either/or” situation. Workers are either dominated or liberated by the technology. Instead of adopting the binary framework of “domination/resistance,” we draw inspiration from Ortner (2006: 110) and find that workers are what she calls “existentially complex” subjects who know and “make and seek meanings” of their situation, simultaneously acting on and being shaped by social and cultural forces.

Using workers’ subjectivity as the implicit nexus to comprehend the agentic practices of workers and their relations to the shaping factors in the platform economy, we aim to show how the specific economic, social, and technological dimensions of platform work intersect with workers’ agentic performance and their meaning-making practices. The ever-changing chameleon platform has generated variant forms of employment relations and management practices that substantially affect workers’ subjectivity (Vallas and Schor 2020) and propel workers to exercise their agency against the platform company’s flexible application of “a portfolio” of management techniques at its disposal (Moore and Joyce 2019). It therefore entails a dynamic model to comprehend workers’ agency, which we call contingent agency. It considers workers’ agency to be locally and contextually specific manifestations inseparable from the networked structure and their social and employment relations that characterise platform work in the Chinese food-delivery service sector. Contingent agency is a heuristic device we develop to show how platform workers make meanings of their labour and defend and negotiate their labour rights against the shifting ground that is conditioned and mediated by the precarious structure of the digital platforms, heterogeneous forms of employment, technological surveillance, and the customer-oriented ideology.

Platformisation of food-delivery service in China

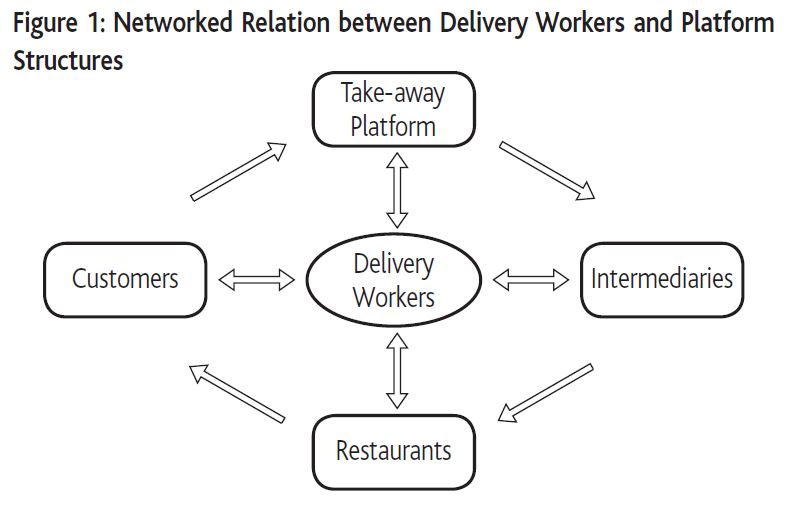

In less than ten years, food-delivery platforms have changed the eating habits of millions of Chinese and reconfigured the relation between consumption and service.[3] By June 2019, more than 400 million people ordered food through the Internet, generating more than 600 billion RMB in transactions in one year (approx. 84 billion USD).[4] The platform-mediated take-away service in China started in 2011, and after several rounds of mergers and acquisitions, the current market is dominated by a duopoly of Meituan and Ele.me – they control more than 90% of the market share. Collectively, the platforms set in motion a logistical supply chain thanks to the prevalence of smartphones. Nowadays the take-away economy has established a multi-layered supply chain involving different market players (Figure 1).

In this logistical supply chain, platform companies have played important roles in connecting delivery workers, intermediaries, restaurants, and customers. The food-delivery platform mediates the online-to-offline transactions that bridge customers to food merchants through the labour pool of delivery workers. On the one hand, the platform tries to attract large numbers of consumers by providing them with on-demand food-delivery service. On the other hand, it collaborates with restaurants, canteens, and food merchants to expand the latter’s customer base by charging the latter a rate of commission. The platform commissions may cost a partnering restaurant 15% to 35% of total revenue, depending on the business size, the daily volume of delivery orders, and the number of platforms the restaurant signs on.

In this logistical supply chain, platform companies have played important roles in connecting delivery workers, intermediaries, restaurants, and customers. The food-delivery platform mediates the online-to-offline transactions that bridge customers to food merchants through the labour pool of delivery workers. On the one hand, the platform tries to attract large numbers of consumers by providing them with on-demand food-delivery service. On the other hand, it collaborates with restaurants, canteens, and food merchants to expand the latter’s customer base by charging the latter a rate of commission. The platform commissions may cost a partnering restaurant 15% to 35% of total revenue, depending on the business size, the daily volume of delivery orders, and the number of platforms the restaurant signs on.

Driven by fierce market competition, the platform companies have launched several rounds of employment relations restructuring. Market leaders such as Ele.me, Meituan, Shansong, and Dianwoda have all outsourced their labour management work to third-party or intermediary temp staffing agencies (TSA) to cultivate their delivery labour pool. The boost of take-away platforms makes courier a popular job category for migrant workers. During the last decade, migrant workers have shifted from the construction and manufacturing industries to the platform-mediated service sectors such as transportation, parcel courier, and food-delivery.[5] As previously mentioned, the number of riders on the food-delivery platform has exceeded 6 million. The unregulated expansion of take-away platforms and their variant collaborations with intermediaries have generated different forms of delivery workers – namely, platform-hired workers, outsourced workers, crowdsourced workers, and restaurant-employed workers. Each type of rider differs in employment relation, management structure, and labour conditions.

Different forms of riders are mobilised by the platform companies to meet the ever-changing needs of the market. Platform-hired workers are couriers who are hired by the platform company and have signed a labour contract with the platform. Outsourced workers are couriers who are hired by third-party temp staffing agencies. They usually don’t have labour contracts but hold a labour agreement with the TSA. Crowdsourced workers are “independent workers” who usually work part time and don’t have labour contracts. As the market has been gradually dominated by Ele.me and Meituan, the number of platform-hired riders has decreased and the outsourced riders and crowdsourced riders have become the main labour force.

As the core of the supply chain for the food-delivery service, riders connect, mediate, and configure their relations between platforms, TSA, restaurants, and customers. They have built subtle and complex relations with various social structures and organisations and displayed diverse forms of agentic performances. The process of platformisation provides us with a way to consider workers’ agency to be an evolving and developing manifestation of workers’ subjectivity in their encounters with different players in the industry and the social structure.

Method

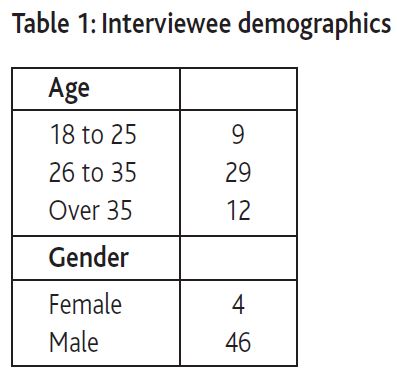

In order to investigate delivery workers’ agentic performances within the platform structures, this study employed ethnographic fieldwork and in-depth interviews as the main methods to collect data. Research participants are from Meituan, Ele.me, and Shansong, which were the dominant take-away platforms in China. From 2017 until late 2019, the research team frequented the stations (zhandian 站點) of the riders in the different districts of Beijing. After building rapport with them, the authors conducted participant observations and more than 40 semi-structured interviews during the three-year period. In April and May 2020, the authors conducted an additional 10 interviews online to examine how delivery workers do their job and perform workers’ agency during the COVID-19 pandemic. The 10 interviewees were recruited via the snowballing technique from the authors’ existing connections in the riders’ community. Table 1 shows the demographic breakdown of the courier interviewees.

The total of 50 interviews each lasted from 30 to 120 minutes. Interview questions revolve around their work history, work conditions, employment relations, and experience with the platform-mediated work environment. Delivery workers were also encouraged to share stories and opinions on how they manage their work and interact with the platform(s). In the latest round of interviews, we added new questions about the impact of the novel coronavirus on their work. The authors also joined a WeChat group of 500 riders to observe how they communicate, what content was posted, and how they create solidarity and subjectivity through daily communicative practices.

The total of 50 interviews each lasted from 30 to 120 minutes. Interview questions revolve around their work history, work conditions, employment relations, and experience with the platform-mediated work environment. Delivery workers were also encouraged to share stories and opinions on how they manage their work and interact with the platform(s). In the latest round of interviews, we added new questions about the impact of the novel coronavirus on their work. The authors also joined a WeChat group of 500 riders to observe how they communicate, what content was posted, and how they create solidarity and subjectivity through daily communicative practices.

All interviews were anonymised and transcribed, and then coded by the authors together with all observational notes. Informed by the grounded theory perspective (Corbin and Strauss 2014), we generated insights about worker’s agency from the qualitative data by constantly situating the riders through their lens and in their social context. Consequently, the analysis is driven and centred on worker’s narratives. In order not to impose existing theoretical frameworks on the riders, we converse with existing studies and theories when the workers’ experience echoes, complicates, or contradicts them.

Contingent agency in the food-delivery platforms

Platform-based affordance and constraints

As far as the platform-mediated labour process is concerned, Moore and Joyce (2019) warn against an uncritical fixation on the algorithms, which risks overlooking the “two-way” relationship in employment. Workers resist, as they contend, whenever they find where the “pressure points are and levels and effectiveness of resistance increase” (Moore and Joyce 2019: 8). The volatility of the platform-mediated market for the food-delivery service gives rise to multiple places of those “pressure points.” Among them are the interstices riders discover in the competitions between different platform companies. During the past decade, the market for platform-mediated food-delivery service in China has evolved into a duopoly with multiple small players. To compete against one another, different platform companies have launched several rounds of labour recruitment by raising financial incentives and providing various forms of part-time jobs, which present more ongoing job opportunities for riders. For savvy delivery workers, every round of competition between platforms means a chance to make a choice in their job, or even lifestyle.

It’s hard for people like me to find another full-time job. This job is an easy choice because I can decide when and where to go (…). I do this because I don’t want to be monitored [like those working] in the factories. When I have time, I log on and take some orders; if I don’t want to work today, I can stay in my bed all day. (Daxing District, Beijing, 13 July 2019)

Xu has been working as a part-time rider intermittently in Ele.me for three years. He believed that the platform economy provided him with more autonomy regarding schedules and locations. He was good at catching the ebbs and flows of the market demand. Usually he took peak-hour delivery requests during the day, or those in extreme weather or when there are transportation controls and other emergent conditions, as the piece rate tends to surge under those circumstances. He managed to join several WeChat groups of riders, where people share information about the locations and times of “big [well-paid] orders” (dadan 大單). The informational function of social media (Qiu 2016) helped extend Xu’s social networks, which in turn made it convenient for Xu to straddle two jobs.

Another case came from Wang, a 王牌騎士 (wangpai qishi, a top level rider known as “trump rider”) in the Shansong platform, which provides intra-city courier service. Starting from 2016, Wang has been working as a courier for four years.

[The job] works for me. It’s quite flexible. If I want to work, I log onto the system. If not, I close it and do my own things. But people are greedy... For example, at the very beginning, I was very happy with earning 100 RMB from the platform. But soon, I wanted to make more [money]. I wanted 200 RMB… Now, I can make 400 to 500 RMB [a day], and I am still not satisfied. (Chaoyang District, Beijing, 10 June 2018)

Unlike Xu, who took delivery jobs intermittently, Wang developed the job into a full-time one, although he joined Shansong as a part-time courier. When talking about his work in Shansong, Wang felt motivated, and believed his efforts had been rewarded by the platform. In his narratives, flexibility not only brings him extra income, but also the freedom to choose what he wants to do. Wang worked more than 10 hours every day at Shansong so he could maintain the “trump rider” level and have a higher piece rate.

As the expanding platform capitalism reconfigures the pattern of employment relations, it also affords certain opportunities and choices for workers, although such affordance appears to be fleeting and unpredictable. Unlike the early generation of workers who emphasise stability and security (e.g. Kuruvilla et al. 2011), the young generation of digital workers such as Xu places more value on flexibility and self-decision than a guaranteed nine-to-five job. Our study found that extra income and self-decision are among the most appealing reasons for migrant workers who do not have an “iron rice bowl” (tiefanwan, 鐵飯碗, guaranteed lifetime employment) to flock to the food-delivery platforms. Some workers also consider the delivery job to be a good transitional choice that offers them the income and time to think about what to do in the future. The lack of entrenched attachment to any platform position generates a pool of workers who have developed a different mental orientation toward their job. The prevailing ethos of the platform workers has shifted toward placing value in the “slashie” style (Alboher 2007), self-entrepreneur (Freeman 2015), and individual’s economic gains, which are shown in their agentic performance.

However, compared with sectors such as manufacturing and construction, platform-based employment is rife with volatility, uncertainty, and a lack of workplace-based social interaction among peers, as the job is undertaken through mobile apps without the physical presence of co-workers. Most of the time, workers have to adapt themselves into a work situation that lacks mutual collaboration and guidance. Workers have to play guerrilla warfare with the platform as they do not know when and where they may lose the job or need to find another one. In this sense, workers’ agency is contingent not only upon the assorted forms of precarious and transitory job opportunities on offer in platform capitalism at its current stage, but also upon workers’ certain degree of identification with the flexibility and risk embedded in platform work. Workers embracing the risks and uncertainties associated with platform work cannot be fully explained by the concepts of self-exploitation or false consciousness. This is where workers’ subjectivity comes into play, wherein agency is articulated through meanings and earnings made by workers as well as through the “affect” (Ortner 2016) workers generate from their own choice of being a platform labourer.

Workaround strategies to wrestle with capitalistic logic

Numerous studies suggest that workers are not only “knowing subjects” (Ortner 2016), but are also able to develop an array of tactics to game the platform system and resist the platform-facilitated labour management (see, e.g. Chen 2018; Moore and Joyce 2019). The “workaround strategies” (Lee et al. 2015) developed by riders in our study can best be described as improvised efforts to follow and seize on the high rate. In practice, these efforts include riders’ behaviour to frequently change to the platform that pays a higher piece rate, or to work on multiple platforms, or a combination of the two. To follow and seize on the high rate even primes some riders to devise individual or collaborative actions, such as installing cheating software, to manipulate the system.

Zhang was a courier in “Starbucks Delivers” of Ele.me, and during the last three years, he had changed his job five times among different delivery platforms. When asked why he had to change the platforms he worked for so frequently, Zhang stressed the relevance of income: “The grass is always greener… When the pay is getting low, everyone goes to the platforms that can earn them more money.” To organise riders into a hierarchy with a pay scale is common to Chinese food-delivery platforms, most of which also deploy varied degree of gamification (Sun 2019). Confronting this calculated labour management, workers chose to tilt towards money instead of stability.

Zhang’s rationality was echoed by his co-worker and fellow villager Cai. When at Baidu Deliveries, Cai was once a station manager whose job was to stay in the station office and monitor the real-time performance of each rider. Baidu Deliveries paid stable wages and bonuses to station managers and prohibited them from providing delivery service. But Cai discovered Baidu’s crowdsourcing platform (then a new app) offering “a very high piece rate,” which could rise to 5 or 6 RMB for noon peak time deliveries. So Cai and a station manager nearby organised several “riders in their respective stations” to deliver orders from the crowdsourcing platform. Unfortunately, they were caught by the company and penalised with public warnings and a fine of 500 RMB for Cai. In retrospect, Cai attributed the discovery of his policy violation to the use of his national ID to register on the crowdsourcing platform. “I could have used other people’s ID,” he concluded, “as other people did.”

But the penalty did not deter Cai from seizing on the high piece rate available on the market. After that, Cai quit his job and joined a group of more than 300 couriers to complete what was known as “the assigned orders” (zhipai dan 指派單). The assigned orders were “very lucrative” in Cai’s eyes, with an additional pay of 5 RMB for each order within 5 km and of 10 RMB each for orders between 5 and 10 km. Cai stayed until the group was disbanded when Baidu’s food-delivery business merged into the Ele.me platform.

From work, riders also accumulated certain knowledge about the algorithmic control of their labour process and developed tactical practices to manipulate the algorithms for their own interests. In 2017, when a bonus war took place between Ele.me and Meituan, food-delivery workers colluded with some canteens and restaurants to place artificial orders, for which riders waited nearby to ensure they would be allocated for the delivery. Riders then pretended to have completed the delivery by simply clicking the completion button on the app. Once the fake orders were finished, riders and the participant canteens and restaurants would share the cash bonus awarded by the platforms. Some workers went so far as to install bots to bypass certain platform-imposed restrictions (e.g. location or single platform) or to help them automatically get better paid jobs. All these questionable individual or collaborative manipulations of platform algorithms are known as shuadan (刷單, meaning “to refresh for better orders”), which is fraudulent and punishable by the platform.

These openings in the forms of economic gains profoundly shift workers’ attitude and motivations for job changes in two respects. First, information about piece rates and the differences of even a couple of Chinese yuan between platforms or types of riders is made more visible to workers than in other sectors, and it is designed as such by the platforms to directly incentivise workers at a more granular level. Consequently, although social ties remain important for riders (e.g., in Cai’s experience), riders demonstrate and exert a certain level of agency to mitigate against their precarious socio-economic status by taking advantage of the information and their knowledge about the workings of the algorithms. This points to the increasing significance of market information, as opposed to the “trial and error” method (Tian and Xu 2015), in platform workers’ decisions to change jobs. Secondly, studies show that migrant workers change their jobs to accumulate human and social capital (e.g., knowledge and skills) so that after several job changes, some workers are able to climb the occupational ladder or land a better paid job (Wang and Wu 2010; Tian and Xu 2015). It would be premature to determine the accumulation of human and social capital in riders’ job change patterns, but economic benefit seems to become the sole motivation for their job mobility, while the foundation for knowledge and skills accumulation is undermined in platform capitalism.

Although workers’ counter-algorithm actions are common and ongoing, it must be noted that they are not only risky, encountering frequent failures and platform crackdowns, but also contingent on the specific technological affordance of the platforms. Usually, no sooner do workers develop a tactic to game the system than the platform upgrades its app, fixing the bugs or intensifying surveillance on workers. Workers’ gained knowledge and skills are quickly made obsolete by the platforms, which weakens their transferability to the next job. Platforms’ technology hegemony, embodied in the continuous upgrades and enhanced algorithmic control through workers’ mobile phones, circumscribes worker’s agentic performance. To a certain degree, workers’ order-farming and algorithmic manipulation activities would inadvertently help the platform companies detect technological bugs, for one, and to generate data to strengthen the platform competitiveness on the market, which ultimately reproduces the capitalistic logic and the power structure (Fleming and Spicer 2003).

Social relations: Cultivating renqing

As the take-away platform is an immediate supply chain, its efficient operation requires each part to function well. However, timely delivery depends not only on the riders but also on restaurants. Riders often complain about the slowness and inefficiency of restaurants in food preparation, which may cause an overtime on their delivery. Since On Time Delivery (OTD) is a key performance indicator for the platform and the intermediaries to evaluate delivery teams, both the riders and the team leaders (or station managers) take on-time delivery seriously. For example, Ele.me requires every delivery worker to complete orders of less than three kilometres in 29 minutes. If the overtime rate of one team exceeds 5%, both the workers and team leader face a bonus cut from their income. Consequently, riders and managers develop certain tactics to maintain a good relationship with the restaurants, which straddles between business ties and the brotherly social relations that are best understood through the cultural lens of guanxi (關係 meaning social relations) and renqing (人情 meaning reciprocal social and moral obligations). In Fei’s (1992) conceptualisation, guanxi connotes both social networks and relations “from the soil” and the moral and ethical principle of mutual reciprocity (renqing) to discipline the interpersonal relationship. For the latter, guanxi and renqing can be instrumental and subject to conscious cultivation or even manipulation (Barbalet 2015).

Wu was a Shansong leader in Chaoyang District, Beijing, who was in charge of 20 groups of 200 delivery workers. Wu reached out to 60 restaurants in the covered business areas to foster the social relations with them. He visited the restaurants one by one, introducing himself to the restaurant managers and staff. Wu and his colleagues also frequented these places and drank with staff who were responsible for the take-away business. According to Wu, to “get a top place in the competition against other delivery teams” motivated him to engage in the socialising activities:

As long as the restaurant prepares the food fast enough, my bros [riders] can deliver them on time. Otherwise, it threatens the on-time delivery of the entire team and hinders bros in my team from getting [the rewards] they deserve… [When there is a conflict in cooking at the restaurants], I would call them. Usually they give me mianzi (literally mean “face” in Chinese) and finish our orders first. (Online interview in Beijing, 1 May 2020)

Wu figured that one restaurant may sign up on several take-away platforms, and its treatment of delivery orders from different platforms matters. During the peak time, Wu’s amicable relationship with the restaurants pays off as they may prioritise orders for his Shansong team and thus help decrease the chance of delayed deliveries. Wu’s team has been among the top three best performing Shansong delivery teams in Beijing for the last three years, which can be attributed to Wu’s deliberate cultivation of an amicable relationship with the restaurants.

Furthermore, workers in Wu’s team also mentioned the importance of maintaining good relations with individual staff in the restaurants. For example, Li said, “[it is] important to know the take-away kitchen assistant. S/he decides our sequence to collect the food. If s/he knows you, you would get the food before others (workers from other platforms).” Another worker, Song, kept brotherly relations with cooks in several restaurants. “When I cannot wait any longer, I go directly to the back kitchen to urge them.” He believed this offered him a head start to receive food during rush times.

Embedded in an interrelated supply chain, riders exercise individual agency in a networked yet individualised fashion for which personal “guanxi” and relations “from the soil” (Fei 1992) gain valence. The currency of Wu’s mianzi is acquired through socialising activities with restaurant owners and managers. Workers such as Li and Song become personally acquainted with their counterparts at the restaurant. In a similar manner, both actions help shorten the social distance between riders and the restaurants, attaching human feelings and moral obligations (renqing 人情) to the otherwise impersonalised business transaction from food preparation (by the restaurant) to collection (by the rider).

Social relations and community support prove to be significant indicators of workers’ agency (Chan 2013), whereas for delivery workers the platform work-based social relation network is structurally distributed, fragile, and easy to dissolve. Although food-delivery couriers can foster work relations by cultivating instrumental personal ties and collaborative opportunities, these relations and renqing are contingent, transient, and subject to change at any time. Throughout our fieldwork, we found that relatively long-term and stable social relations among workers, canteens, and group managers are hard to maintain due to workers’ high mobility and the constant structural changes of the platform assemblage. For example, Wu’s team has a high turnover rate. Wu spent a large amount of time recruiting couriers and frequenting restaurants whose managers also change from time to time. Even the brotherly relations change within the platform. Li complained that the platform changed too quickly as the kitchen assistant he knew before was transferred to another branch.

Unlike manufacturing workers, for whom the shared workplace and fixed work schedule are conducive to solidarity building, platform workers have been mobilised in a distributed and individualised environment where physical presence and offline gathering are removed from their labour process. Thanks to the penetration of the Internet and mobile apps, platform work becomes “easy-come easy-go” work that allows the labour force to flow and move at a speed never seen before. Workers’ frequent job-hopping and platforms’ transient operating policies undermine the structural social and cultural foundations for workers to establish reliable and long-term social connections. This systematically circumscribes the channels through which platform workers mobilise social capital and cultural bonding to practice their agency.

Counteractions

Although counteractions are one of the most viable manifestations of workers’ agency, they are under-studied among delivery workers. China Labour Bulletin (CLB) has identified food-delivery and parcel couriers among the most contentious workers in the Internet-related economy.[6] Our fieldwork documented how riders mobilise technological and social resources to empower themselves in the face of unbalanced power relations with their employers and the platform companies. Overall, riders tend to participate in protests or disputes caused by unfair treatment and pay-cut related issues.

Wang, mentioned above, was a trump rider. In general, Shansong couriers are grouped into three ranks that correspond to different ways of getting orders and different levels of priority when it comes to automatic job-allocation. Newcomers, with a typical service score of 60, rely on themselves to claim delivery orders (known as order-grabbing, or in Chinese qiangdan 搶單). When newcomers have fulfilled a satisfactory number of completed deliveries and reached a service score of 85 or more, they can apply to become a rider on the dispatch mode (known as order-dispatching, or in Chinese paidan 派單). The highest level of rider on the dispatch mode is called the trump rider, which can only be applied to riders who are already at the dispatch level and have maintained a high service score. Trump riders enjoy the top priority in job-allocation. Both trump and dispatching riders can switch to the mode of order-grabbing and enjoy a higher priority than lower-ranked riders at the order-grabbing level.

In October 2019, Shansong started to subcontract to third-party staffing agencies for recruiting and managing full-time couriers. The subcontracted agencies introduced new couriers to the business and placed them directly at the level of order-dispatching. Wang and other experienced riders found that the platform was treating them unfairly:

It is unfair because we have been working our way through order-grabbing, application for the dispatch mode and so on. We stayed and followed this rule for a couple of years, [especially] during the period of time when the platform company was not doing well. Now that the company is getting better, this is inappropriate. (Online interview in Beijing, 3 May 2020)

After sharing their grievance in several WeChat groups and online forums, Wang’s co-workers organised about 300 experienced riders to stage a protest against unfair treatment at the Shansong headquarters in Beijing’s Haidian District. The local police intervened. After the senior managers of Shansong met with rider representatives, the company decided to place all of the subcontracted full-time couriers at the level of new-comer. This means they would start from grabbing the orders and work their way up.

Shansong riders’ experience of the platform’s arbitrary decision to allow third-party staffing agencies to take over labour recruitment and management is hardly unique. As early as in August 2017, a group of Baidu Deliveries riders successfully organised to defend their labour rights. On 24 August 2017, Baidu announced the merger of its food-delivery platform with Ele.me. Accompanying the merger was an arbitrary bulk transfer of former Baidu-hired riders to third-party temp staffing agencies. This meant that those Baidu riders would become subcontracted Ele.me riders, which violated the labour rights of the former Baidu riders. Cai was a station manager when the transfer took place. He recollected a labour dispute initiated by Baidu riders in Beijing’s Chaoyang District.

After consulting a lawyer who took the case pro bono, five or six riders took the case to the labour dispute arbitration committee in Chaoyang District in September 2017… It took about half a year… But the riders successfully obtained compensation. (Online interview in Beijing, 1 May 2020)

When COVID-19 broke out in China before the Chinese New Year, most of the couriers in Beijing had left their jobs and returned to their hometowns. When the city was in a lockdown, food delivery orders surged with fewer workers on duty, which inevitably intensified the workload for the remaining riders in Beijing. However, these workers didn’t get overtime payments. In the last week of January, 2020, couriers of Meituan in Beijing worked more than 15 hours per day, and most of them were exhausted and overwhelmed. Riders at one zhandian in Haidian district organised a work stoppage, demanding that the intermediary and the platform compensate their overtime. Given the mounting pressure and the special circumstances of the pandemic, the platform company and intermediaries agreed to give each worker overtime pay during the New Year holiday. However, after the holiday, as the pandemic gradually came under control, despite a continued surge of orders and a labour shortage, the platform and intermediaries refused to pay workers overtime, and the confrontation between workers and the platform persisted.

With the expansion of TSA into the platform-mediated food-delivery service sector, the unfair treatment of subcontracted riders is rampant, while full-time platform-hired riders are in decline. Wage arrears and arbitrary pay cuts by either the platforms or the staffing agencies have become the main reason for food-delivery riders to take legal or collective action in the absence of official trade unions. A glimpse into the national picture of food-delivery riders’ collective actions from June 2019 to June 2020 revealed that 16 out of 17 protests and strikes were caused by either wage arrears or pay cuts. Although our fieldwork found that almost half of our informants either have participated in collective actions themselves or were aware of collective actions taken by others, workers’ collective actions lead to mixed results. The lack of systematic social support and the highly volatile and individualised work conditions contribute to workers’ contemporary agentic performance.

Conclusion

The article offers a rich and nuanced account of the contextual and at times contradictory means by which food-delivery workers exercise their individual and collective agency for self-empowerment. This account makes a meaningful and timely contribution to the fields of platform labour studies and worker agency studies by bringing the worker narrative to the fore. It finds that along with the unpredictable expansion of the platform economy, platform workers have gained some measure of control and self-decision regarding when, where, and how to participate in platform work. More importantly, our findings contradict the popular myth of impenetrable black-boxed management of workers (see Moore and Joyce 2019), as riders have displayed sufficient knowledge about how the platform works and what managerial techniques are deployed against them. Platform workers have also developed workaround strategies, mobilised personal relations and social resources, and participated in social activism and counteraction against platform capitalism.

However, the wide range of agentic performances of delivery workers entails a careful conceptualisation of workers’ agency in the context of the platform-mediated work environment. Platform-mediated work is characterised by a highly fluid and heterogeneous workforce, fierce market competitions, arbitrary algorithmic control, and unpredictable management practices (van Dijck et al. 2018; Sun 2019; Chen and Sun 2020). As food-delivery workers are mostly migrant workers, their informal employment status substantially undermines their collective bargaining power (Fan 2021), which cannot be offset by the wide array of agentic performances demonstrated in their lived working experiences. In particular, the high fluidity of food-delivery riders is in line with an extant trend of shortening job tenure among the young generation of Chinese migrant workers (Tsinghua Sociology Research Team 2013), which results in a minimum level of skill development and upward social mobility. The absence of institutional empowerment for migrant workers in general exacerbates the precarity of food-delivery workers in the platform economy.

Consequently, their agentic performances are largely circumstantial and reactive to the precarious and unpredictable platform assemblage. But this by no means suggests that workers are all but act to extend the capital’s logic. Nor is our intention to advocate a “false optimism” (Lee 2016: 328) that workers’ agentic performance would lead to either political or institutional empowerment, which is difficult to achieve without the political will of party leaders. On the contrary, we conceptualise the notion of “contingent agency” and flesh out multiple contingent factors so as to capture both the structurally vulnerable position of the food-delivery workers and the multifold, ongoing, and proactive tactics and strategies developed and manoeuvred by workers. Contingent agency lays bare the unstable situation where platform workers have to constantly calculate their current and prospective income, act on foreseeable opportunities to increase or maximise earnings, engage in expansion of personal and social ties, participate in negotiation of wages and labour rights, and if needed, mobilise themselves for collective actions.

Wood and Lehdonvirta (2019: 1) argue that there is a “structure antagonism” between workers and the platforms that “manifests as perceived conflicts over platform fees, pay rates, and lack of worker voice.” “Structured antagonism” is one of the distinctive contributing factors to workers’ participation in collective actions even when they regard themselves as self-employed. Our findings complicate and compliment this argument, as workers’ agentic performances are external mechanisms that are developed to tackle the unpredictability of platformisation rather than endogenous self-awareness. We contend that the notion of contingent agency offers a new perspective to the eternal problem of control and resistance in labour studies. Platform workers are more like temporarily agentic subjects whose empowerment and selfhood are contingent on the highly unstable platform structures of which they are arguably a crucial component and contributor (Vallas and Schor 2020). It is worth noting that although food-delivery riders in China are capable of organising for resistance and counteractions, their collective power is not yet comparable to that of factory workers in China and elsewhere to be mobilised for pro-labour legislative or regulatory reforms.

The current landscape of the delivery workers’ agency is likely to evolve and include new forms of agency responding to the ongoing restructuring of employment relations by the platforms, temp staffing agencies, and other forces. The framework of contingent agency will help to lay bare the manifestations and trends. While it remains to be seen whether the documented contingent agency will generate lasting impact on capital-labour relations, it will be interesting to see further studies comparing the rights consciousness of platform workers and factory workers. As the labour platforms expand globally, the concept of “contingent agency” is applicable beyond the specific national context of China, especially for countries where the informal economy dominates and labour regulations are lagging. Digital platforms will continue to be a critical topic in labour studies. Further research on the co-evolution between the ever-changing platform landscapes and platform workers’ agentic performances will be welcomed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors of the special issue – Chris K.C. Chan, Eric Florence, and Jack Linchuan Qiu – for their valuable comments and suggestions on the manuscript. Thanks to Ting Wang and Qianyu Zhang for their assistance in interview coordination in 2018, 2019, and 2020.

The authors made equal contributions to the article.

Ping Sun is Assistant Professor at the Institute of Journalism and Communication, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, No. 9 Panjiayuan Dongli, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China 100023 (sunp@cass.org.cn).

Julie Yujie Chen is Assistant Professor at the Institute of Communication, Culture, Information & Technology (ICCIT) (Mississauga) and the Faculty of Information at the University of Toronto, Canada, 3359 Mississauga Rd. Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6 Canada (julieyj.chen@utoronto.ca).

Manuscript received on 24 August 2020. Accepted on 16 December 2020.

References

ALBOHER, Marci. 2007. One Person Multiple Careers. New York: PT Mizan Publika.

BARBALET, Jack. 2015. “Guanxi, Tie Strength, and Network Attributes.” American Behavioral Scientist 59(8): 1038-50.

BIELER, Andreas, and Chun-yi LEE (eds.). 2018. Chinese Labour in the Global Economy: Capitalist Exploitation and Strategies of Resistance. Vol. 1. London and New York: Routledge.

CANT, Callum. 2019. Riding for Deliveroo: Resistance in the New Economy. Cambridge and Medford: Polity Press.

CHAN, Chris King-chi. 2013. “Community-based organizations for migrant workers’ rights: The Emergence of Labour NGOs in China.” Community Development Journal 48(1): 6-22.

CHEN, Julie Y., and Ping SUN. 2020. “Temporal Arbitrage, the Fragmented Rush, and Opportunistic Behaviors: The Labor Politics of Time in the Platform Economy.” New Media & Society 22(9): 1561-79.

CHEN, Julie Yujie. 2018. “Thrown under the Bus and Outrunning it! The Logic of Didi and Taxi Drivers’ Labour and Activism in the On-demand Economy.” New Media & Society 20(8): 2691-711.

CORBIN, Juliet M., and Anselm L. STRAUSS. 2014. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (4th edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

DYER-WITHEFORD, Nick. 2015. Cyber-proletariat: Global Labour in the Digital Vortex. Toronto: Between the Lines.

EMIRBAYER, Mustafa, and Ann MISCHE. 1998. “What is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103(4): 962-1023.

FAN, Lulu. 2021. “The Forming of E-platform-driven Flexible Specialisation: How E-commerce Platforms Have Changed China’s Garment Industry Supply Chains and Labour Relations.” China Perspectives 1(124): 29-37.

FEI, Xiaotong. 1992 [1947]. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

FIESELER Christian, Eliane BUCHER, and Christian Pieter HOFFMANN. 2017. “Unfairness by Design? The Perceived Fairness of Digital Labour on Crowdworking Platforms.” Journal of Business Ethics: 987-1005.

FREEMAN, Carla. 2015. Entrepreneurial Selves: Neoliberal Respectability and the Making of a Caribbean Middle Class. Durham: Duke University Press.

GIDDENS, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

GRAHAM, Philip. 2000. “Hypercapitalism.” New Media & Society 2(2): 131-56.

KURUVILLA, Sarosh, Ching Kwan LEE, and Mary. E. GALLAGHER (eds.). 2011. From Iron Rice Bowl to Informalization: Markets, Workers, and the State in a Changing China. Ithaca, New York and London: Cornell University Press.

LAZAR, Sian, and Andrew SANCHEZ. 2019. “Understanding Labour Politics in an Age of Precarity.” Dialectical Anthropology 43(1): 3-14.

LEE, Ching Kwan. 2016. “Precarization or Empowerment? Reflections on Recent Labor Unrest in China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 75(2): 317- 33.

LEE, Min Kyung, Daniel KUSBIT, Evan METSKY, and Laura DABBISH. 2015. “Working with Machines: The Impact of Algorithmic and Data-driven Management on Human Workers.” Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: 1603-12.

LUCIO, Miguel Martinez, and Stewart PAUL. 1997. “The Paradox of Contemporary Labour Process Theory: The Rediscovery of Labour and the Disappearance of Collectivism.” Capital & Class 21(2): 49-77.

MOORE Phoebe V., and Simon JOYCE. 2019. “Black Box or Hidden Abode? The Expansion and Exposure of Platform Work Managerialism.” Review of International Political Economy 27(4): 926-48.

ORTNER, Sherry B. 2006. Anthropology and Social Theory: Culture, Power, and the Acting Subject. Durham: Duke University Press.

QIU, Linchuan Jack. 2016. “Social Media on the Picket Line.” Media, culture & society 38(4): 619-33.

SMITH, Chris, and Ngai PUN. 2018. “Class and Precarity: An Unhappy Coupling in China’s Working-Class Formation.” Work, Employment and Society 32(3): 599-615.

SUN, Ping. 2019. “Your Order, Their Labor: An Exploration of Algorithms and Laboring on Food Delivery Platforms in China.” Chinese Journal of Communication 12(3): 308-23.

TAYLOR, Charles. 1985. What is Human Agency. New York: Cambridge University Press.

TIAN, Ming, and Lei XU. 2015. “Investigating the Job Mobility of Migrant Workers in China.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 24(3): 353-75.

Tsinghua Sociology Research Team. 2013. “‘短工化’: 農民工就業趨勢研究” (“Duangonghua”: nongmingong jiuyequshi yanjiu, “Short-termism”: A study on employment trends among migrant workers). Tsinghua Sociological Review 6: 1-45.

VALLAS, Steven, and Juliet B. SCHOR. 2020. “What Do Platforms Do? Understanding the Gig Economy.” Annual Review of Sociology 46(1): 273-94.

VAN DIJCK, José, Thomas POELL, and Martijn DE WAAL. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

WANG, Mark Y., and Jiaping WU. 2010. “Migrant Workers in the Urban Labour Market of Shenzhen, China.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 42(6): 1457-75.

WOOD, Alex, and Vili LEHDONVIRTA. 2019. “Platform Labour and Structured Antagonism: Understanding the Origins of Protest in the Gig Economy.” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3357804 (accessed on 11 June 2020).

ZAJAK, Sabrin, Egels Zandén NIKLAS, and Piper NICOLA. 2017. “Networks of Labour Activism: Collective Action Across Asia and Beyond. An Introduction to the Debate.” Development and Change 48(5): 899- 921.

ZHANG, Lin. 2020. “When Platform Capitalism Meets Petty Capitalism in China: Alibaba and an Integrated Approach to Platformization.” International Journal of Communication 14(1): 114-34.

[1] “Digital Economy Opens up Employments Space for 200 million People,” Xinhuanet, 12 March 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/tech/2019-03/12/c_1124222712.htm (accessed on 26 May 2020).

[2] “Factories trapped in hard recruitment, while the number of delivery riders is growing,” Tencent.com, 5 May 2020, https://new.qq.com/omn/20200505/20200505A0F1O900.html (accessed on 26 May 2020).

[3] In this article, food-delivery platform and take-away platform are used interchangeably.

[4] “Statistical Reports on the Internet Development in China,” China Internet Network Information Center, 2020, https://cnnic.com.cn/sjzs/SLAtj/ (accessed on 1 June 2020).

[5] “Gig economy is the reservoir of labour after COVID-19,” LinkedIn Netease, 2020, http://mp.163.com/article/FE5RDH630514D39S.html (accessed 3 June 2020).

[6] “The state of labour relations in China, 2019,” China Labour Bulletin, 13 January 2020, https://clb.org.hk/content/state-labour-relations-china-2019 (accessed on 8 February 2021).