BOOK REVIEWS

Protesting with Text and Image: Four Publications on the 2019 Pro-democracy Movement from Hong Kong Civil Society

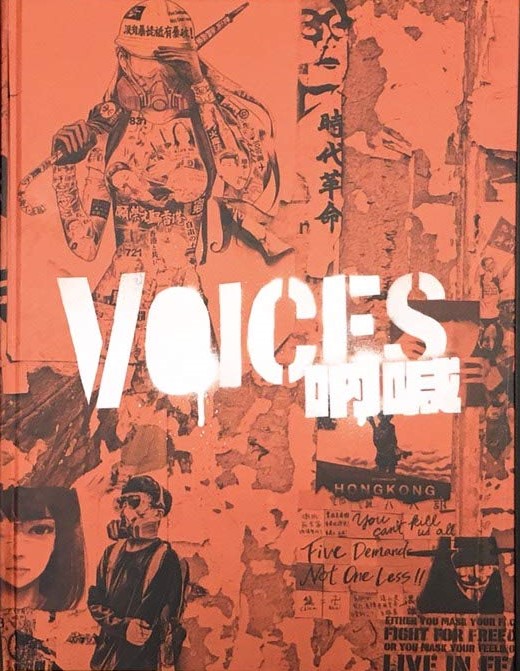

[caption id="attachment_100079483" align="alignnone" width="176"] ABADDON, Childe (ed.), 2020. Voices 吶喊. Hong Kong: Rock Lion.[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_100079485" align="alignnone" width="226"]

ABADDON, Childe (ed.), 2020. Voices 吶喊. Hong Kong: Rock Lion.[/caption]

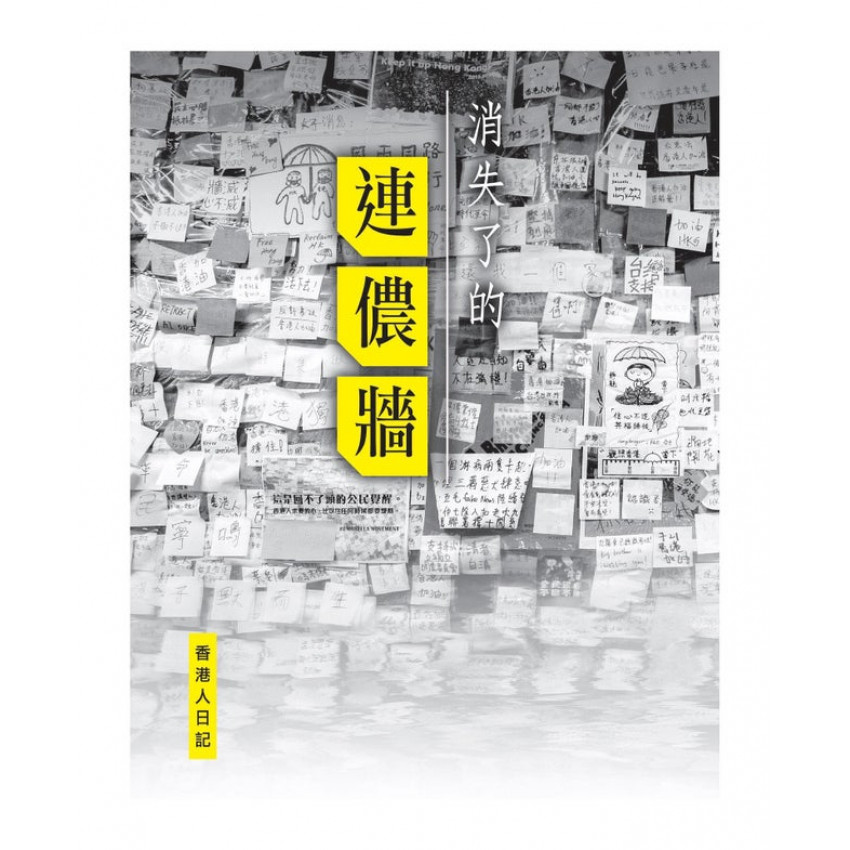

[caption id="attachment_100079485" align="alignnone" width="226"] GUARDIAN OF HONG KONG 愛護香港的人 (ed.), 2020. The Disappearing Hong Kong Lennon Walls - Diary of Hongkongers 消失了的連儂墻 – 香港人日記. Hong Kong: Isaiah 以賽亞出版社[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_100079481" align="alignnone" width="187"]

GUARDIAN OF HONG KONG 愛護香港的人 (ed.), 2020. The Disappearing Hong Kong Lennon Walls - Diary of Hongkongers 消失了的連儂墻 – 香港人日記. Hong Kong: Isaiah 以賽亞出版社[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_100079481" align="alignnone" width="187"] ICH BIN EIN HONG KONGER, Keith B. RICHBURG, and Kin-ming LIU (eds.), 2020. Defiance 誰衛我城. Hong Kong: Rock Lion.[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_100079487" align="alignnone" width="221"]

ICH BIN EIN HONG KONGER, Keith B. RICHBURG, and Kin-ming LIU (eds.), 2020. Defiance 誰衛我城. Hong Kong: Rock Lion.[/caption]

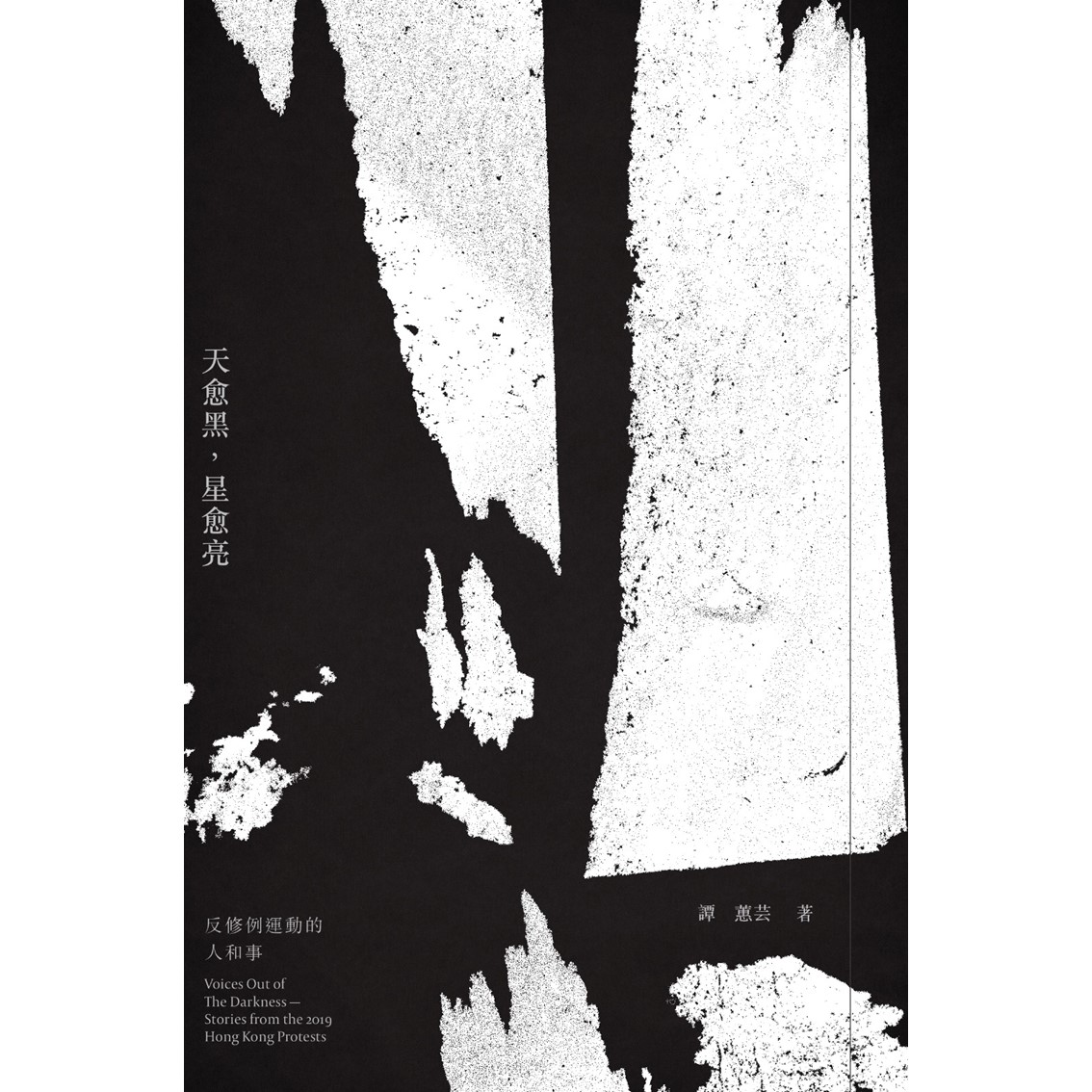

[caption id="attachment_100079487" align="alignnone" width="221"] TAM, Vivian Wai-wan 譚蕙芸. 2020. Voices Out of The Darkness - Stories from the 2019 Hong Kong Protests 天愈黑 星愈亮 – 反修例運動的人和事. Hong Kong: Breakthrough 突破[/caption]

TAM, Vivian Wai-wan 譚蕙芸. 2020. Voices Out of The Darkness - Stories from the 2019 Hong Kong Protests 天愈黑 星愈亮 – 反修例運動的人和事. Hong Kong: Breakthrough 突破[/caption]

Introduction

On 4 September 2019, the Hong Kong government officially announced the withdrawal of a highly contentious extradition law that had sent more than two million citizens swarming the streets in opposition. As Hong Kong participants in the 2019 Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill protests (Anti-ELAB protests for short) were having a brief moment of exhilaration, the repression had just begun. Unlike the 2014 Umbrella Movement, in which the previous government adopted the “attrition” approach (Yuen and Cheng 2017), the current government of Carrie Lam opted this time for direct suppression.

The Hong Kong authorities took highly repressive action against citizens’ freedoms of expression, of assembly, and of the press, while deliberately refusing to address the protests’ real cause. In their official publications and statements, they also disproportionately accentuated protesters’ response while playing down the police’s arbitrary violence and aggressive behaviour.[1] Peaceful protests such as the 12 June sit-in escalated into major clashes with the police firing more than 150 rounds of tear gas, a dozen bean bag rounds, and rubber bullets.[2] In view of this distortion of events, and parallel to their active participation in street actions, many citizens decided to record this important chapter of Hong Kong history in their own words and images. A flurry of zines (Tong 2020) and journalistic (Chan 2020; Lau 2020), literary, or artistic publications (Hon 2020; The Initium 2020) were promptly released during and after the start of the 2019 Anti-ELAB movement. In this essay, four non-academic books in English and Cantonese are reviewed to highlight a few common defining features of these publications, including the circumstances under which they were published, how the 2019 protests are narrated from the perspective of ordinary protesters and observers, and how protesters keep fighting for democracy with creative means in spite of government repression. Widely advertised in activist and academic networks, these four books were selected as representing a sample of the broad range and diversity of publications, points of view, and media used to record the movement (photography, graphic design, protest art, and nonfiction narrative).

In Voices Out of The Darkness - Stories from the 2019 Hong Kong Protests (Tam 2020), Vivian Tam Wai-wan 譚蕙芸 put together 80 feature stories on her venture as a special correspondent during the 2019 Anti- ELAB protests. Beside following the protests closely, Tam is also a lecturer of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, where one of the major police clashes broke out.[3] Published by independent publisher Breakthrough 突破, Voices Out of The Darkness is not only a day-to-day field report of an independent journalist in hard hat and safety goggles, but also a profound reflection on the historicity, humanity, and deontology of journalism. The Disappearing Hong Kong Lennon Walls - Diary of Hongkongers (Guardian of Hong Kong 2020) is edited by a devout Christian under the pseudonym “Guardian of Hong Kong” (Oiwu Hoeng Gong dik jan 愛護香港的人). Published by a lesser-known unit called Isaiah 以賽亞出版社, the work unfolds as a personal journal, with each section starting with an inspirational quote from the Bible, followed by the author’s direct sentiments towards the injustice witnessed each day under the rule of a nonrepresentative government. It is also presented as a bulletin board of messages from Hongkongers from all walks of life, weaving individual voices into a collection of grievances and democratic demands. Finally, the small independent publisher Rock Lion released two graphic hardbacks, Defiance (Ich Bin Ein Hong Konger, Richburg and Liu 2020) and Voices (Abaddon 2020). Defiance is a photographic documentary of Hong Kong protesters shedding tears and blood on the unrecognisable streets throughout the year of 2019, both artistic and authentic. Voices, on the other hand, is a collection of hundreds of pro-democracy graphic designs that were plastered on the city’s walls, bringing out the creativity and wittiness of Hong Kong protesters. Childe Abaddon, the editor of Voices, is himself a prolific protest artist in the Anti-ELAB protests, and unless unnamed, some of the 60 Defiance photographers are major contributors to international and local news outlets, while its editors are renowned journalists Keith Richburg and Liu Kin-ming 廖建明. The four publications are distributed online and in selected independent bookstores, reaching out to a broad Cantonese and English-speaking readership (Defiance and Voices are written in both languages). Although a few scholars have promptly worked on a chronology of the 2019 protests (Dapiran 2020; Wasserstrom 2020), these four titles should not be underestimated for their historical value and their contribution to understanding Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movements.

Recent challenges for Hong Kong publishers

Once renowned for its free environment and thriving publishing industry, Hong Kong has recently faced major challenges in this sector, in particular in 2015, when five staff members of Causeway Bay Books were kidnapped and tried in mainland China.[4] According to the Hong Kong Basic Law, “Hong Kong residents shall have freedom of speech, of the press and of publication; freedom of association, of assembly, of procession and of demonstration; and the right and freedom to form and join trade unions, and to strike.”[5] Nevertheless, these freedoms are no longer guaranteed since the implementation of the National Security Law (NSL) on 30 June 2020,[6] as it overrides the Basic Law and broadly aims at suppressing any possible threat to national security. Although the NSL includes reassurances that Hong Kong citizens’ freedoms of press and publication are still under the protection of the Basic Law, publishing pro-democracy content may now result in charges of subversion, sedition, terrorism, and colluding with foreign forces.[7]

Soon after the promulgation of the NSL, the Hong Kong government adopted draconian measures to silence dissidents and “promoters” of pro-democracy messages,[8] pressing on with the erasure of pro-democracy titles from public libraries[9] and the city’s largest annual book fair.[10] As a result, some publishers have started to self-censor,[11] and during the course of writing this review, the website for Defiance and Voices was no longer publicly accessible.

At the same time, the existence of independent bookstores and publishers is threatened by the monopoly of Chinese-funded companies. Sino United Publishing Group 聯合出版 (集團) 有限公司, the parent of three major Hong Kong publishing groups (Joint Publishing 三聯書店, Commercial Press 商務印書館, and Chung Hwa 中華書局), is in fact fully controlled by officials of the PRC Central Government Liaison Office, who also own Hong Kong’s biggest pro-Beijing newspapers, Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po. The three major publishing groups have dozens of franchises all over Hong Kong and own more than a half of all local bookstores. They produce and sell a vast selection of books, including textbooks, posing a grave danger to freedom of expression and free access to knowledge in Hong Kong.[12] Due to the unhealthy dominance of state-owned commercial publishing houses and the NSL, concerned publishers have gradually migrated their vending points to online platforms, and distribute only in selected independent physical bookshops – which was the case for the four reviewed books.

Documenting Hong Kong people’s history

Like other titles, these recent publications on Hong Kong protest movements denote an effort to document ordinary people’s history of political and social engagements. People’s history, or “history from below,” is a historical narrative genre focusing principally on the oppressed, the powerless, and the marginalised, in contrast to political history, which concentrates mainly on people in power (Chesneaux 1976; Thompson 1966; Zinn 1990; Bhattacharya 1986: 4-5). In a strict sense, Voices Out of The Darkness, The Disappearing Hong Kong Lennon Walls, Defiance, and Voices do not fall neatly into the category of people’s history. However, they chronicle events from a perspective of ordinary protesters and observers, providing a different side of history from academic works, the narratives from pro-government newspapers, and official reports. These documentations of how the 2019 protests were lived and perceived by ordinary protesters and observers constitute invaluable primary sources for history writing, whether in text or image, and could contribute substantially to future academic works.

As a long-time journalist who has received recognition from her readers and peers, Vivian Tam Wai-wan recounts her personal experience while reporting the Anti-ELAB protests in her latest book. Voices Out of The Darkness manifests her sophistication in human depiction. Her writing style is distinctly influenced by feature story writing, which focuses largely on the individual instead of the event. Whereas many feature stories require adequate studies on the person of interest, subjects penned in Tam’s latest book are oftentimes merely strangers and ordinary people. She lends an ear to the faintest voices in the loudest chants of pro-democracy slogans, attempting to draw readers’ attention to the grievances of the Anti-ELAB protesters: students, civil servants, taxi drivers, housewives, foreign domestic helpers, and so on. From an underage girl’s tears during her first arrest (p. 127-32) to an old popsicle vendor’s nonchalant response to tear gas (p. 435- 39), every voice tells a different story, and every story counts. The author reports in an exceptionally calm manner, even when stuck in the violent clash between riot police and university students at her alma mater on 11 November 2019 (p. 355-63). Voices Out of The Darkness proposes an extensive inspection on the social context of the population of Hong Kong in the recent political turmoil, allowing for a better understanding of Hong Kong protesters’ demands.

Defiance, or Who Protects Our City? (Seoi wai ngo sing 誰衛我城) in literal translation, is a work of photojournalism documenting major events in the 2019 protests in both Cantonese and English, corroborated with a wide range of photographs of street protests in thick tear gas. Some images capture the lack of professionalism of the Hong Kong Police Force (HKPF) in handling the Anti-ELAB protests, contradicting their claims of being restrained and always using appropriate force;[13] for instance, when an anti-riot police officer strikes his baton on a detained protester’s head (p. 80), when a police officer aims a canister of pepper spray directly at the face of peaceful civilians who were video-recording him (p. 82-3), or when another officer armed with a crowd-control rifle provokes protesters from a distance with hand gestures (p. 87). Another case in point that is well-illustrated in the book is the HKPF’s handling of the Yuen Long 21 July 2019 mob attack.[14] While the authorities claimed that the HKPF did not notice any irregular activities that might have led to the violent clash that night, photo evidence in the book shows police conversing with mobsters in white T-shirts holding bamboo rods prior to the incident (p. 141), corroborating allegations of police-mob collusion.[15]

[caption id="attachment_100079489" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] A police officer fires tear gas at protesters whilst other police officers point and use other types of weaponry. Credit: Alexander Mak. Defiance, p. 74-5.[/caption]

A police officer fires tear gas at protesters whilst other police officers point and use other types of weaponry. Credit: Alexander Mak. Defiance, p. 74-5.[/caption]

While The Disappearing Hong Kong Lennon Walls may appear to be less polished in comparison with the previous two titles, it presents the narratives and opinions of ordinary protesters and the civil society throughout 2019. In this publication with a strong focus on woleifei (和理非, peaceful, “rational,” and non-violent protesters), the editor celebrates a popular mode of collective political expression and creativity in Hong Kong since 2014. The first Hong Kong Lennon Wall emerged in the middle of the Umbrella Movement, taking form as a hybrid of the original John Lennon Wall in Prague, and the Democracy Wall (Minzhu Qiang 民主牆) of post-Cultural Revolution China (1978-1979). In early October 2014, protesters started putting up Post-it notes written with supportive messages on a wall around the Central Government Offices in Admiralty, on Hong Kong Island. This practice gradually became popular, attracting people outside of the occupied area to come and participate with their own notes. Spreading out several meters in length, the notes composed a colourful wall of wishes for authentic universal suffrage. In 2019, a second generation of Hong Kong Lennon Walls, in plural, took over every possible corner of the city: tunnels, footbridges, bus stops, and walls outside of shopping malls. They were not only covered by messages in colourful square paper like five years before, but also by all sorts of graphic posters on A4 size paper, sometimes as large as a billboard. The Hong Kong Lennon Walls soon became highly contentious spaces between protesters and counter-protesters,[16] and underwent regular removal by the authorities.[17]

In this publication, the author mourns the demolished Hong Kong Lennon Walls and invites pro-democracy protesters to their restoration by co-authoring the book. Contributors to Lennon Walls may come from the grassroots or from the civil society, all showing their support for the pro-democracy movement. Civil society has long been an active participant in Hong Kong’s social movements (Loh 2007; Wong and Chan 2017), and more than 70 pro-democracy labour unions were formed by January 2020 in the hope of influencing the upcoming Chief Executive election.[18] Religious groups were also visible on protests sites, especially at the beginning of the movement, when pacifist Christians joined by non-religious citizens stood in front of armed police singing “Sing Hallelujah to the Lord” for hours to defuse tension and protect protesters.[19] As a person of faith, the author receives enthusiastic responses from religious people in his book, as well as other members of civil society, such as labour union representatives and social workers.

Creativity in times of protest: From murals to messaging applications

As the Hong Kong government on 4 October 2019 invoked the colonial era’s Emergency Regulations Ordinance to prohibit protesters from wearing masks during unauthorised assembly,[20] in addition to the police ban on mass protest events,[21] Hong Kong protesters have been pressured to dissent in less visible yet more creative ways than street rallies, such as engaging in Lennon Wall decoration. Lennon Walls provide protesters with a platform to voice their discontent, and also to connect with likeminded Hongkongers. Both The Disappearing Hong Kong Lennon Walls and Voices have archived a significant collection of creative posters from pro-democracy protests. In Lennon Walls, you may find a Christmas tree made of Post-it messages (p. 25), government officials’ photos and their “crimes” printed on poker game cards (p. 209), and a series of drawings of jungmou (勇武, radical protesters) as anime characters (p. 159).

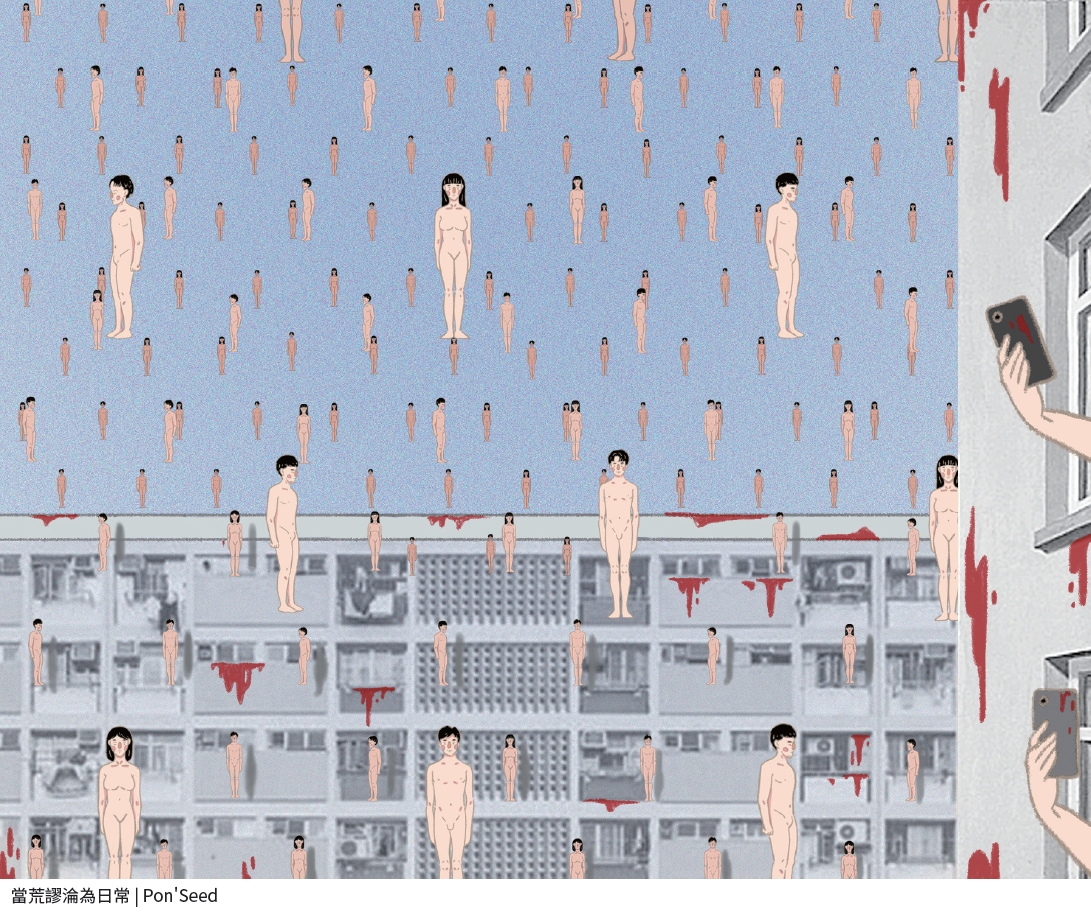

[caption id="attachment_100079491" align="aligncenter" width="1091"] 當荒謬淪為日常 (When Absurdity Becomes Everyday Life). Credit: Pon’ Seed. Voices, p. 181.[/caption]

當荒謬淪為日常 (When Absurdity Becomes Everyday Life). Credit: Pon’ Seed. Voices, p. 181.[/caption]

In Voices, Hong Kong protesters have not only created derivative works of globally renowned paintings, such as Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (p. 132-3) and Magritte’s Golconda (p. 181), but also artworks that reflect Hong Kong’s local culture, such as ghost money depicting government officials in costume and makeup (p. 154-55), protest slang illustrations with Cantonese, Jyutping, and English annotations (p. 220- 21), calligraphy (p. 232-3), and computer typefaces (p. 230-1; 234-5). In terms of content, these artworks can be sorted into five major categories: supportive messages, slogans, protest events calendars, concise summaries to debunk misinformation, and protest art. Hong Kong Lennon Walls have progressively morphed from an emotional support station into a terrain of resistance.

[caption id="attachment_100079493" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Hell Bank Notes. Credit: Ricky. Voices, p. 154-5.[/caption]

Hell Bank Notes. Credit: Ricky. Voices, p. 154-5.[/caption]

It is worth mentioning that protest art created by Hongkongers is not only popular in physical form, but also in the digital realm. Some protest artists turned government officials and celebrities into Internet memes, some of which can be seen in print in Lennon Walls (p. 85). LIHKG 連登討論區, a popular local online forum, became an important information and creative centre during the 2019 protests. The statue of Lady Liberty Hong Kong, one of the most iconic symbols of the movement, was designed by a group of anonymous members of LIHKG, using 3D printing technology to create a three-metre-tall white sculpture of a female protester wearing the typical outfit of protesters, such as yellow helmet, safety goggles, and gas mask. Some protesters made art with the forum’s signature animal stickers (p. 247; 255; 271) and displayed them on the various Lennon Walls. Others created protest-themed stickers with the forum’s mascots, which were disseminated across multiple social media platforms and appeared again on Lennon Walls.

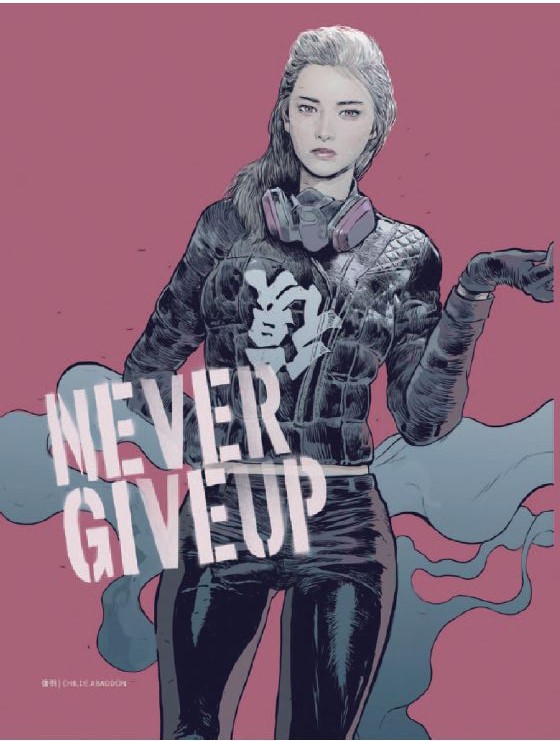

[caption id="attachment_100079495" align="aligncenter" width="403"] Don’t Give In. Credit: Jeffery Kit Quang. Voices, p. 81.[/caption]

Don’t Give In. Credit: Jeffery Kit Quang. Voices, p. 81.[/caption]

Negotiating free speech and safety: Anonymity, pseudonyms, and collective expression

Mask-wearing has become a common practice for Hong Kong protesters as a result of their insecurity over increasing surveillance in the digital age, which is sometimes juxtaposed with the CCP’s intrusive policing systems in Xinjiang.[22] Hong Kong protesters have generally adopted a uniform outfit (black clothing and face mask) when participating in rallies and assemblies, in order to avoid being identified. It is notable that three out of four publications in this review are under anonymous authorship. Beside the adoption of anonymity by book writers and publishers, this phenomenon is also evidenced by the concealment of some contributors’ identities and the use of nicknames across all four publications. This reflects the growing fear of Hong Kong citizens as a result of the authorities’ mass arrests and prosecutions, as well as the “doxing” culture on the Internet. In The Disappearing Hong Kong Lennon Walls, contributors can be classified into three types: public figures using real names (e.g. co-founder of Occupy Central Benny Tai Yiu-ting 戴耀廷 (p. 184-5), university lecturer Bruce Lui Ping-kuen 呂秉權 (p. 258-60)), writers signing with Cantonese or English nicknames (e.g. Richard (p. 47- 9), Ah Jan 阿恩 (p. 284)), and writers under pseudonym. As identifiability decreases, the tendency to reveal personal details and evidence of protest participation, including illegal acts, increases. For example, “Polar bear mom 北極熊媽媽,” who has two teenage children, details her role as member of a resource team in the 12 June 2019 protest (p. 88-9); “Kagura” reveals his/her agony over being a child from a police family (p. 144-5); “Bou Lo 保羅” expresses his guilt for failing to protect his fellow jungmou protesters (p. 232-3). All these anonymous accounts allow readers to take a closer look at the daily lives and thoughts of ordinary protesters during the Anti-ELAB protests. Without the protection of anonymity, these testimonies may not exist, as any protester could fall prey to the NSL once identified.

In Voices Out of The Darkness, Tam reports on several peaceful assemblies held by newly established pro-democracy labour unions, such as the Hong Kong Aviation Staff Alliance 航空同業陣線 (p. 91-2) and the Union of New Civil Servants 新公務員工會 (p. 112-5). Most interviewees are given nicknames for privacy reasons. Interviewed assembly participants speak out frankly on their fear of losing their jobs once identified, but what they fear the most is losing the ability to express their political views freely. In fact, their fear is not unfounded, given that employees from various industries were sacked for showing support to the pro-democracy movement in public, or even on their personal social media accounts.[23] The undercurrent of denunciation is quietly sweeping across various workplaces and the Internet, deepening the social fissure resulting from the antagonism between citizens holding different political views. Tam also brings in journalistic ethics in her prologue to explain the use of anonymity in news reporting, which could be a circumstantial practice and requires adequate experience in the field. She admits having received requests from interviewees to leave their real names out of her articles (p. 42). She refers to Tom Grundy’s[24] editorial decision to not blur a protester’s face during the LegCo occupation on the night of 1 July 2019, defying hundreds of requests from netizens (p. 46).

On the other hand, anonymity provides those who cannot openly attend street protests a sense of safety in creating protest art. Voices has collected not only artworks of popular local cartoonists such as Ah To 阿塗 (p. 195) and Cuson Lo (p. 173), but also drawings by anonymous contributors. Anonymity facilitates the free circulation of these works online, through messaging applications, or simply on Lennon Walls. The flourishing of anonymous protest art on Lennon Walls has encouraged protesters to create their own materials and quickly replenish them with newly-designed posters as soon as they were removed by government-appointed cleaners or vandalised by pro-Beijing gangs.

[caption id="attachment_100079529" align="aligncenter" width="515"] 復倒. Credit: Childe Abaddon. Voices, p. 113.[/caption]

復倒. Credit: Childe Abaddon. Voices, p. 113.[/caption]

Conclusion

The momentum of the current pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong was significantly hindered throughout 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and the implementation of the Hong Kong National Security Law have effectively paralysed all large-scale protests. It is unclear whether mass rallies and assemblies will resume once the pandemic is under control. Meanwhile, the Court of Final Appeal has recently ruled that the Hong Kong mask ban will be upheld constitutionally in unlawful assemblies,[25] which is a victory for the government and a serious blow to Hong Kong protesters who have been repeatedly denied permission to attend lawful demonstrations. In the face of incessant mass arrests and prosecutions in the name of national security, there is very little room for civil disobedience. Voices Out of The Darkness, The Disappearing Hong Kong Lennon Walls, Defiance, and Voices summarise the events of the 2019 protests in text and image, giving prominence to the diversity of participants and the creative protest methods they utilise in daily resistance, including publishing protest-themed books as a form of resistance. These publications also raise awareness about the difficulties of being a pro-democracy protester in Hong Kong and how these individuals come together, often in anonymity, forming collective actions that delineate a people’s history.

Terrie Ng is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Rennes 1. Université de Rennes 1, 2 rue du Thabor, CS 46510, 35065 Rennes CEDEX, France (terrie-tsz-yiu.ng@etudiant.univ-rennes1.fr).

References

BHATTACHARYA, Sabyasachi. 1983. “‘History from Below.’” Social Scientist 11(4): 3-20.

CHAN, Holmes, ed. 2020. Aftershock: Essays from Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Small Tune Press.

CHESNEAUX, Jean. 1976. “Histoire par en haut et histoire par en bas. Les masses populaires en histoire.” In Du passé, faisons table rase ?, Paris: La Découverte. 138-47.

DAPIRAN, Antony. 2020. City On Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong. London: Scribe.

HON, Lai-chu. 2020. Darkness Under The Sun 黑日. Hong Kong: Acropolis 衛城出版.

LAU, Ryan Chun-kong. 2020. Yuanlang heiye – wo de jiyi he zhongren de jiyi 元朗黑夜 _– 我的記憶和眾人的記憶 (The Dark Night of Yuen Long - My Memories and Everyone’s). Hong Kong: Lauyeah Production Limited.

LOH, Christine. 2007. “Alive and Well but Frustrated: Hong Kong’s Civil Society.” China Perspectives 2(99): 40-55.

THE INITIUM 端傳媒. 2020. Time and Tide - Photographs of the Anti- Extradition Bill Protests in Hong Kong 潮湧 - 香港反修例運動影像紀錄. Hong Kong: The Initium 端傳媒.

THOMPSON, E. P. 1966. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage Books.

TONG, Kin Long. 2020. “DIY Print Activism in Digital Age: Zines in Hong Kong’s Social Movements.” ZINES, 2020/1: 65-76.

WASSERSTROM, Jeffrey. 2020. Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink. New York, NY: Columbia Global Reports.

WONG, Yiu Chung, and Jason K.H. CHAN. 2017. “Civil Disobedience Movements in Hong Kong: A Civil Society Perspective.” Asian Education and Development Studies 6(4): 312-32.

YUEN, Samson, and Edmund W. CHENG. 2017. “Neither Repression Nor Concession? A Regime’s Attrition against Mass Protests.” Political Studies 65(3): 611-30.

ZINN, Howard. 1990. A People’s History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row.

[1] See for instance Poon Lai Fong, Bob Howlett, and Information Services Department, (eds.) Hong Kong Year Book 2019. (Hong Kong: Government of Hong Kong SAR, 2020). https://www.yearbook.gov.hk/2019/en/.

[2] SCMP Reporters, “As It Happened: Hong Kong Police and Extradition Protesters Renew Clashes as Tear Gas Flies,” South China Morning Post, 12 June 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/ hong-kong/politics/article/3014104/thousands-block-roads-downtown-hong-kong-defiant-protest. See also Amnesty International, “How Not To Police A Protest: Unlawful Use of Force by Hong Kong Police,” 21 June 2019, https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ASA1705762019ENGLISH.pdf.

[3] K.K. Rebecca Lai. “How Universities Became the New Battlegrounds in the Hong Kong Protests,” The New York Times, 19 November 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/18/world/asia/hong-kong-protest-universities.html.

[4] Alex W. Palmer, “The Case of Hong Kong’s Missing Booksellers.” The New York Times, 4 March 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/03/magazine/the-case-of-hong-kongs-missing-booksellers.html.

[5] Hong Kong: The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. 1 July 1997, Article 27. https://www.basiclaw.gov.hk/en/basiclawtext/chapter3.html.

[6] Javier C. Hernández, “Harsh Penalties, Vaguely Defined Crimes: Hong Kong’s Security Law Explained,” The New York Times, 13 July 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/30/world/asia/hong-kong-security-law-explain.html.

[7] Hong Kong: The Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. 30 June 2020. Article 4. https://www.gld.gov.hk/egazette/pdf/20202448e/egn2020244872.pdf.

[8] Iain Marlow and Natalie Lung, “Hong Kong Says Common Protest Slogan Calling for ‘Revolution’ Is Now Illegal Under National Security Law,” Time, 2 July 2020, https://time.com/5862683/hong-kong-revolution-protest-chant-security-law/.

[9] AFP, “Democracy Books Disappear from Hong Kong Libraries, Including Title by Activist Joshua Wong,” Hong Kong Free Press, 4 July 2020, https://hongkongfp.com/2020/07/04/democracy-books-disappear-from-hong-kong-libraries-including-title-by-activist-joshua-wong/.

[10] Katheleen Magramo, “Hong Kong Book Fair Exhibitors Urged to Exercise ‘Self-Discipline’, Avoid Selling ‘Unlawful’ Books as Security Law’s Passage Looms,” South China Morning Post, 23 June 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/3090312/hong-kong-book-fair-exhibitors-urged-exercise-self.

[11] Sarah Wu and Joyce Zhou, “Editing History: Hong Kong Publishers Self-Censor under New Security Law,” Reuters, 14 July 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hongkong-security-publishers-idUSKCN24F09P.

[12] See for instance Michael Forsythe and Crystal Tse, “Hong Kong Bookstores Display Beijing’s Clout,” The New York Times, 19 October 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/20/world/asia/hong-kong-bookstores-display-beijings-clout.html; and Blake Schmidt, “The Publishing Empire Helping China Silence Dissent in Hong Kong,” The Japan Times, 18 August 2020, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/08/18/asia-pacific/politics-diplomacy-asia-pacific/publishing-china-hong-kong-media/.

[13] See for instance the HKPF Commissioner’s justification for the use of live bullets: “盧偉聰稱警開槍射中五生 合理合法 ” (Lu Weicong cheng jing kaiqiang she zhongwusheng heli hefa). Ming Pao, 10 February 2019. https://news.mingpao.com/ins/%E6%B8%AF%E8%81%9E/article/20191002/s00001/1569947228319/.

[14] Kelly Ho. “Explainer: From ‘Violent Attack’ to ‘Gang Fight’: How the Official Account of the Yuen Long Mob Attack Changed over a Year.” Hong Kong Free Press, 21 July 2020. https://hongkongfp.com/2020/07/21/from-violent-attack-to-gang-fight-how-the-official-account-of-the-yuen-long-mob-attack-changed-over-a-year/.

[15] This event was briefly mentioned as “a group of people attack protesters and commuters at Yuen Long Station” in the Hong Kong Year Book. Poon, Howlett, and Information Service Department, “Calendar of Events 2019.” vii.

[16] Holmes Chan, “26-Year-Old Woman in Critical Condition after Knife Attack at Hong Kong ‘Lennon Wall,’” Hong Kong Free Press, 20 August 2019, https://hongkongfp.com/2019/08/20/26-year-old-hong-kong-woman-critical-condition-knife-attack-lennon-wall-tseung-kwan-o/.

[17] “食環署清理 連儂牆 950次, 油尖旺區次數最多,” (Shihuanshu qingli «Liannong qiang» 950 ci, you jian wang qu cishu zuiduo) Stand News, 4 June 2020, tinyurl.com/pmsqbp3r.

[18] Sarah Wu, “Hong Kong Workers Flock to Labor Unions as New Protest Tactic,” Reuters, 10 January 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hongkong-protests-unions-idUSKBN1Z9007.

[19] “Hong Kong Protests: How Hallelujah to the Lord Became an Unofficial Anthem,” BBC News, 22 June 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-48715224.

[20] Mary Hui, “A Brief History of Government Efforts to Stop People from Wearing Masks,” Quartz, 4 October 2019, https://qz.com/1721901/hong-kong-anti-mask-law-a-history-of-mask-bans-around-the-world/.

[21] Austin Ramzy, “Hong Kong Police Ban a March to Protest Mob Violence,” The New York Times, 25 September 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/25/world/asia/hong-kong-protest-yuen-long.html.

[22] Chris Buckley and Paul Mozur, “How China Uses High-Tech Surveillance to Subdue Minorities,” The New York Times, 22 May 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/world/asia/china-surveillance-xinjiang.html.

[23] Reuters Staff. “Cathay Pacific Says Has Fired Two Pilots over Hong Kong Protests.” Reuters, 14 August 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hongkong-protests-cathay-pacific/cathay-pacific-says-has-fired-two-pilots-over-hong-kong-protests-idUSKCN1V413C.

[24] Co-founder and editor-in-chief of Hong Kong Free Press, a non-profit, Hong Kong-based English-speaking newspaper.

[25] Reuters Staff, “Hong Kong Court Rules Mask Ban Constitutional for All Public Meetings,” Reuters, 21 December 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/hongkong-politics/hong-kong-court-rules-mask-ban-constitutional-for-all-public-meetings-idUSKBN28V0CC.