BOOK REVIEWS

Ruins, Ruination, and Fieldwork Photography

Introduction

This article is a reflection on urban ruins, fieldwork, and photography. In line with this special issue, its purpose is to explore how these intersect in the context of researching the contemporary Chinese city and to critically assess practices of documenting and narrating China’s urban transformations. To illustrate these connections in a preliminary way, I begin with a photograph taken in 2011 during a scorching July day in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, in the course of an extended fieldwork stint in that municipality, and consider a number of ways of viewing the photo that, taken together, illuminate some of the stakes of ruin imagery and the role of the visual in documenting field sites. In so doing, I seek to highlight what Mike Crang terms the “scopic regimes” (2003) of geography and related controversies over the truth value of images in general and of ruins specifically.

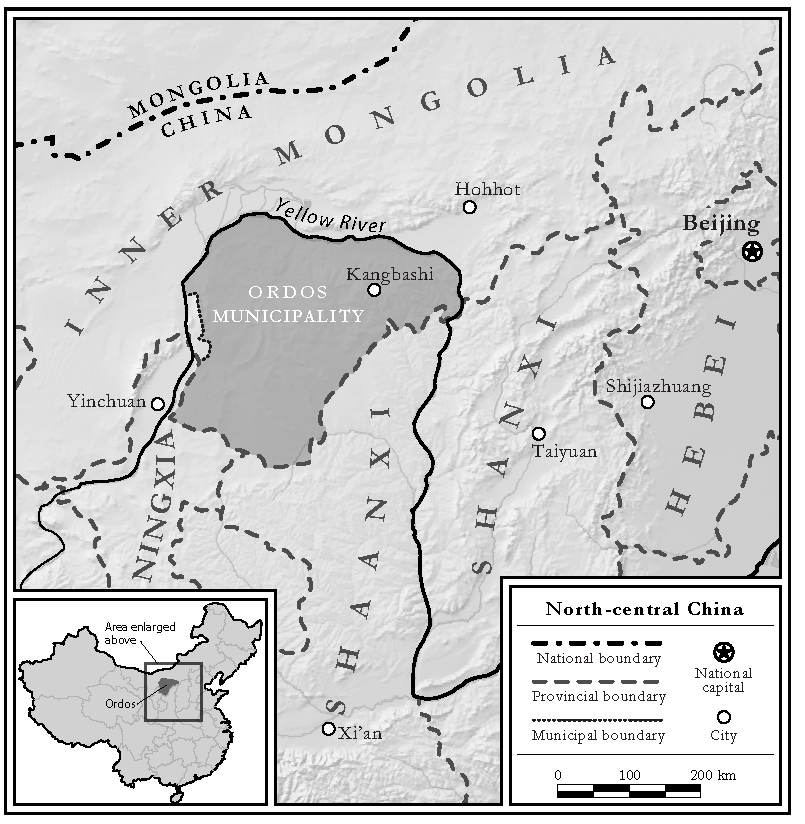

Map 1. Ordos

Figure 1. Ordos 100 villa, 2011. Credit: author.

Figure 1. Ordos 100 villa, 2011. Credit: author.

To start, without the affordance of any contextualising information, a viewer of Figure 1 sees a poured-concrete structure. In its bare concrete massing, the modernist angular building looks similar to a military bunker. It appears unfinished, and because there is neither machinery, scaffolding, nor workers, the building does not appear to currently be under construction. Little more can be drawn from the image than this simple description of its central subject. Fuller context might inform the viewer that the structure is one of 100 planned luxury villas in a residential development on the outskirts of the Kangabashi New District in Ordos. The villa project, titled Ordos 100 (E’erduosi 100 鄂爾多斯 100), was curated by the artist-activist Ai Weiwei and organised by a local developer hoping to sell the villas to the city’s class of coal and real estate barons made wealthy over the previous decade by a tremendous local energy resource boom (Ulfstjerne 2016a). When the photograph was taken, however, Ordos’ real estate market was shaken by an oversupply crisis, the developer had fled town, and the Ordos 100 project was left in a state of suspended animation. The few villas under construction at the time of the market crash in the winter of 2010-2011 were left exposed to the elements, which is the state in which they were found. A property manager, who kept watch over the site, offered to give a tour of the villas under construction. With this context in mind, the photographed structure comes into sharper focus as potentially symbolic of the collapse of Ordos’ real estate sector. But there is an even larger context to the image. During the year or so before this photograph was taken, Ordos had been lampooned in media around the world as ground zero of China’s “ghost city” (guicheng 鬼城) problem, whereby massive, speculation-driven new construction projects in multiple cities around the country spawned vast urban spaces with scant residents. The implication of the ghost city phenomenon, dramatised by the seeming unlikely emergence of a major new city in an isolated corner of a peripheral provincial territory, was that China’s overheated investment-driven economy in the 2000s was on the verge of collapse. News reports made this connection explicit.[1] Seen in this light, the photo fits alongside the raft of imagery and commentary focused on China’s ghost cities, which depict depopulated and abandoned new urban developments in ways reminiscent of what Kathy Korcheck has termed “speculative ruins” (2015) to describe built environments thrown up in a frenzy of financial speculation and then abandoned.

As the description above lays out, the photograph of the building is inherently ambiguous. Originally, it was taken as a form of documentation produced along with written fieldnotes and was stored with other assorted data during fieldwork. It was, in a sense, visual data intended for personal reference collected and kept in a private digital photo archive as part of a research aimed at exploring urbanisation and resource extraction in Ordos. However, staged in a certain way with an appropriate amount of contextualising information and an audience socialised in the aesthetics of ruins, the same villa might readily appear to a different set of viewers as an urban ruin, at which point it enters a global discourse of ruins popularised in recent decades through an abundance of textual and visual commentary (DeSilvey and Edensor 2013). An honest appraisal then leads me to ask of myself: am I not the intended audience for precisely this type of ruin imagery, and was producing a ruin image not my intention? While ruin photography is surely a global fashion, the viewership for such imagery is understood to be a narrow subset of cultural elites, no doubt inclusive of social science practitioners. Having followed closely the ascending popularity of the ghost city trope and its reliance upon photographs of depopulated urban expanses in ambiguous states of ruin, I was well aware at that moment that the villa photographed here resonated the discourse of ruins and was, at some level, aesthetically aligned with the ruin genre, echoing similar images from post-industrial Detroit, the Ruhr Valley, Japan’s Hashima Island, and other locales that have received considerable scholarly (Vergara 1999; Millington 2013; Lyons 2018) and artistic attention[2] in recent years. Though my agenda during research was not to generate images of urban ruins per se, photographs like this one, of which I produced and retained scores for my image archive, might readily be classified as such. What interests me in this essay is the entanglement that this ambiguity of classification instantiates. What counts as data, and how might urban change be represented? Though social scientists seem loath to address the aestheticisation of data, how might photographs of urban ruins work productively to illuminate processes of change that have transformed China? How might aesthetics actually help understand processes that are not easily represented in what commonly is understood as data proper?

Questions such as these emerge when considering that China’s transformations over the past several decades have been marked by construction on a monumental scale (Hsing 2010), and the flipside to construction has naturally been demolition and destruction. The ubiquity of destruction is necessarily the case, as China’s physical environment was built atop things that were already present, including everything from factories, residential neighbourhoods, and infrastructures, to whole villages. To build the new usually requires a process of destruction. Thus, debris of varied description and new construction have been inseparable components of China’s historic development drive during the reform period. Images of change in place are bound to feature evidence of destruction not just as a precursor to growth but its necessary complement and conjoined partner.

Spatial transformation and ruin in contemporary China

Since 2000, China saw a proliferation of massive urbanising projects that failed to quickly gain population and therefore stood largely empty for stretches of time. As such, these giant urban projects straddle a boundary between construction and ruin, for it remains unclear whether they will ever attain the density that such spaces are designed to achieve, or whether they are on the cusp of falling into decay and ruin. These projects began to be labelled as ghost cities in a wave of news reports and scholarly literature starting around 2010 (Shepard 2015; Woodworth and Wallace 2017). In much of the reporting on ghost cities, these sites are deemed to symbolise rash overbuilding and looming systemic crises in China’s urbanisation. In some scholarship, urbanisation where the form of the city is erected without its human substance is discussed as a kind of pathology (Sorace and Hurst 2016). When labelled with such nomenclature, ghost cities appear as failed speculative developments akin to those left in the wake of property booms around the world. The uncertain futures implied by the term ghost city being applied to new construction further exemplifies how construction and ruin coexist as simultaneous material realities in China’s everyday landscapes. This ambiguity also points to the conceptual slippage between construction and ruin in rapidly urbanising contexts. It is not always clear, in other words, nor can it ever be, whether speculative development will end up as a completed project or slide into ruin. Ruin is always a looming possibility, not just at the end of a structure’s life cycle, but throughout its existence, including during the construction phase. The uncertainty to which this alludes must be understood as an intrinsic feature of speculative development and is a feature that photography of ghost cities attempts to represent, as the example of the image at the outset of this article sought to show.

A remarkable feature of the attention paid to the specific phenomenon of China’s ghost cities has been its aestheticisation through photography. As I have argued elsewhere, the photographic medium has been crucial not just in documenting ghost cities, but in creating the phenomenon of ghost cities itself (Woodworth 2020). Imagery of ghost cities consistently pictures these spaces in states of semi-completion and voided of population, lending them a dramatically eerie impression of abandonment and ruin. This manner of figuring these new urban spaces as ruins helps draw attention to the ways financial speculation in the built environment generates unstable combinations of construction and destruction (Kitchin, O’Callaghan, and Gleeson 2014). What is significant in the case of China’s ghost cities is that they were rarely, in any visually obvious way, already failed when represented in images. The onset of decay and debris that conventionally defines ruins is not in evidence. Moreover, the broader narrative of China in the early 2000s was one of relentless growth, not crisis and decay. Instead, what is distinct about photographic representations of China’s ghost cities is that they are pictured as “instant ruins,” to echo Robert Smithson’s term (2011), where new development indexes ruination. Although ghost cities are depicted as new and pristine, the impression of the sites’ unsettledness and emptiness carries an implication of ruin. In this way, the photography becomes part of diverse critiques of developmental crises centred on, but not limited to, China’s booming real estate sector. Such imagery also reverberates a tradition in landscape photography associated with the landmark 1975 exhibition The New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape,[3] featuring work by Robert Adams, Louis Baltz, and Nicholas Nixon, among others. Though hardly univocal in approach, the core thrust of new topographical work has been to highlight the human imprint, often destructive, on the land and its human and non-human elements.[4] The destructive aspect in the topographical genre is usually not indexed by debris or evident decay, but rather by the banality of the landscape as a product of capitalist development. When portrayed as mundane city spaces, China’s ghost cities fairly echo this approach.

It is worth noting that ruins in everyday landscapes have been a dominant motif in contemporary Chinese art as well, which provides another link to a broader discourse of ruins centred on China’s urban transformations and to the topographical tradition. Instances of urban demolition, dislocation, redevelopment, real estate frenzies, and so on have appeared recurrently in recent artistic projects (Wu 2012; Wang 2015; Ortells-Nicolau 2017). As Xavier Ortells-Nicolau has argued, by “salvaging and recycling rubble, and reframing it, via photographic technologies, as an aesthetic object, artists re-evaluate the meaning of that by-product of development and aim to reintegrate it anew into society with a critical purpose” (2017: 265). The photography of ghost cities, therefore, arises in an already crowded representational field, where China’s epochal transformations have been figured through diverse renderings of places and communities in various stages of ruin.

The analysis that follows is motivated by the coincidence of the ghost city phenomenon and my own research into urban development in Ordos. The ghost city trope arose through the circulation of images depicting spaces I was at the time inhabiting in my participant observation field research into energy resource extraction and its entanglements with urban planning, design, and finance. Part of my research practice was to document my research sites photographically, and over the course of multiple visits during a six-year period, I amassed an archive of several hundred digital images of urban spaces in Ordos that look like the one presented in Figure 1. Construction, after all, was a defining feature of Ordos at the time, much as it is all across China. What struck me in the wake of fieldwork was the pictorial similarity between images taken as part of journalistic and artistic projects to reveal ghost cities in China, and my own image archive from Ordos.

I am keen, therefore, to place the photographic figuring of ghost cities as speculative ruins into conversation with recent critical ethnographic theorisations of ruin and rubble and, separately, to consider ghost city imagery in relation to my own fieldwork photographs. More specifically, I place side by side images produced within varied artistic projects portraying China’s ghost cities and my own fieldwork images. I use the juxtaposition of photos as an opportunity to reflect on the possibilities and limits of a critical discourse on ruins and ruination. This leads me to address a number of questions that pertain to the ghost city specifically and to ruins more generally: how are photographic images central to the making of ruins and ghost cities? How do the stakes of ruins as an ethnographic heuristic change when the encounter with the ruin is mediated by the photographic image? How do fieldwork images of spaces commonly pictured as ruins confirm or disrupt the idea of ruins? Can we speak of ruins outside of a conceptual commitment to see them as such, and what are the intellectual and political implications of that commitment? The argument here is that identifying and analysing ruins reflects an unavoidably selective and ideological critical stance with important implications for what ultimately is judged to be present. What is revealed by ruins is a function of a discourse on ruins, an aesthetic convention, and scholarly/personal dispositions. As this special issue shows, China is fertile ground for ruin analysis since vast landscapes of debris have been generated in the process of spectacular urban expansion.

Ruins, ruination, and ruin photos

It is widely accepted that ruins carry powerful symbolic resonance by virtue of their indexical relation to large, world-shaping historical forces. According to conventional ruin analysis, the crumbling masonry of ancient Greece and Rome or medieval cathedrals evoke the passage of time and the ephemerality of culture in the face of encroaching nature (Macaulay 1953; Simmel 1965). The dilapidated buildings of Detroit and rusting industrial districts around the world manifest the vagaries of economic cycles and their social consequences (Vergara 1999). Waste and demolition sites, with their anarchic piles of discarded products, conjure the peril and violence associated with environmental degradation, urbanisation, and climate change. Specific objects carrying such diverse symbolic meanings is premised on the conditioning of viewers to a visual rhetoric of ruins, a shared understanding that is uneven in its breadth and depth, and yet one that is undeniably global at this point and rests on a foundation composed of a vast repertoire of writing, art, popular fascination, and scholarship. Ruins thus maintain a strong popular appeal as ways to expose, bear witness to, and interpret tectonic shifts in social life. Consider, for instance, the presence of ruins and ruination in Canadian photographer and environmentalist Edward Burtynsky’s monumental photographic project titled China (2005),[5] exhibited around the world and forming the basis for Jennifer Baichwal’s documentary film about the project titled Manufactured Landscapes (2006).[6]

Collectively across 115 plates, Burtynsky’s China captures images of a country disfigured, dismantled, and destroyed by breakneck change. What we see in image after image are disparate landscapes in various states of ruin and degradation. Images of the Three Gorges Dam construction site are exemplary, and open to view the ordered chaos and gigantic scale of the project, making it appear as a surgical disembowelling of the Earth for the insertion of massive hydroelectric machinery. In a similar vein, images under the thematic heading “Urban Renewal” present panoramic vistas of Shanghai’s resplendent new infrastructure carving through the new high-rise cityscape in ways perhaps imagined but never realised by mid-twentieth-century titans of urban renewal in the West. A striking feature of Burtynsky’s China project is its manner of zigzagging between images of construction and destruction. Apocalyptic scenes of devastation are juxtaposed with depictions of relentless growth and renewal. Curiously, it is only in the scenes of wreckage that human figures enter the frame. The very picture of abjection, these humans are placed amid rubble in the middle ground, too far for individual features to register, yet too close to ignore as key subjects in the images. The placement side by side of rampant construction and destruction, and of people and communities swept up in a tidal wave of change is, of course, hardly coincidental; it advances China’s overarching theme of impersonal creative destruction, that catchphrase of capitalist industrialisation transforming China before our eyes and making the country itself a symbol and real-time spectacle of contemporary planetary ruination.

The emphasis on rubble and ruin in Burtynsky’s China reveals, I believe, two critical aspects that reflect ongoing debates about ruins specifically and about the ways of coming to terms epistemologically with the ambiguous ontological status of ruins; there is nothing inherent to a material that renders it a ruin. First, the reading of specific material qua ruin is inevitably partial and demands, in a critical sense, that it enters into a discourse of ruins; in other words, ruins must circulate in image form. Second, they must follow a certain loose visual grammar, which accounts for the mimicry of global ruin images today from sites around the world. The ideological work of ruins – their capacity to speak in a particular set of codes and for these codes to be mobilised to certain political-cultural ends – is performed in and through such engagements. It is significant, then, that Burtynsky’s narration of ruin fixates on a particular scale – that of China – to propose larger claims about change and crisis in the world as a whole. This association of China with global ruination fits, moreover, in a longstanding tradition of ruin images of China from colonial photography documenting the cataclysmic collapse of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) to the widespread embrace by Chinese artists throughout the twentieth century of ruins as figures through which to reflect upon the country’s calamitous upheavals pre-liberation in 1949 (Jones 2010; Wu 2012). Ruins, in this sense, do not exist externally from their mobilisation within different claim-making projects.

Such a conception of ruins privileges an aesthetic or phenomenological approach to ruins, which asserts that selected objects are vested with palpable auras made accessible to broader audiences through different sorts of expertise and photographic technologies: interpretive, pictorial, curatorial, cameras, publication platforms (online or otherwise).

In contrast to this, recent materialist scholarship has sought to unpack the social significance of ruin and debris embedded in everyday landscapes. The materialist notion of the ruin that has emerged out of these efforts encompasses a range of rubble, debris, and detritus that elite audiences have tended to disregard and thus directly challenges conventional narrativisations of official ruins and sanctioned heritage. It does so by centring quotidian discarded and decaying materials as analytically valuable objects that can help to excavate neglected or marginalised local histories against official narratives developed, in part, through sanctioned ruin objects and heritage spaces. At the heart of the materialist approach to ruin are ground-level, ethnographic encounters with the everyday landscape, including its myriad scattered detritus.

Ann Laura Stoler’s commentaries on materiality and ruination have arguably done the most to broaden the materialist idea of ruin and bring it into wider use. In her seminal article “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination” (2008) and her widely read “‘The Rot Remains’: From Ruins to Ruination,” the introduction of her book on imperial debris (2013), Stoler recasts the ruin in terms of a material artefact containing overlapping and contending histories and multiple temporalities. “To focus on ruins is to broach the protracted quality of decimation in people’s lives, to track the production of new exposures and enduring damage” (ibid.: 11). By thinking of ruins less in terms of debris left behind by history open to discovery by trained experts, and instead to think of imperial histories as processes of ongoing ruination that spread wreckage throughout everyday landscapes, material detritus of all sorts then can be seen to weave together different strands and moments of history that continually activate the past as a vital feature of current-day life. This view posits that the debris and ruins scattered around the world by the ebbs and flows of various imperial movements can provide a powerful heuristic. As such it can counter the class-inflected and Eurocentric nostalgic gazes that historically have structured both the popular practices of ruin gazing and the academic modes of ruin interpretation that ratified these selfsame practices and produced a globe-spanning institutionalised fetishisation of the ruin in official tourist-oriented heritage.

Stoler’s idea of ruination can be seen as a way to undermine the ideological historicisation of conventional ruin tropes and the traditional emphasis on ruins as merely aesthetic objects: “To think with imperial ruins,” she avers, “is to emphasise less the artefacts of empire as dead matter or remains of a defunct regime than to attend to their reappropriations and strategic and active positioning within the politics of the present” (2008: 196). Following Stoler, Gastón Gordillo (2014) notes how mundane remnants of decay and destruction can prove highly revealing in ways that are overshadowed by bourgeois conceptions of the official ruin. Rejecting the bourgeois notion of ruin in favour of rubble, he argues that attending to the unremarkable and uncelebrated detritus of our landscapes presents a methodological opening for unpacking social processes in place beyond sanitised official histories and its sanctioned ruins. “The destruction of space and its resulting rubble are constitutive of the materiality of space. (…) Rubble, in short, is the path toward further historicizing and politicizing our understanding of the materiality of space and its immanence: that is, of space as we know it in this world” (ibid.: 263). Rubble is conceived here as a form of anti-ruin.

Seeing ruins and ruination in China and its ghost cities

Both conceptions of ruins – as sanctioned official history and everyday detritus – have powerful resonance in China, where built and natural environments contain traces of long and contentious histories, as well as abundant debris generated by recent and ongoing construction. Scholars of urban development have placed significant focus on the politics of demolition and relocation over the past couple decades (Hsing 2009; Shao 2013; Wu 2015; Shin 2016). This period of rampant urbanisation and the rise of a powerful real estate sector stimulated all manner of conflicts and controversies around the destruction of homes and communities, a process Shao Qin referred to as “domicide” (2013). Research on urban demolition, however, has tended to be on the political economy of land development.

A more limited number of studies, upon which this special issue builds, focuses on ruin, disrepair, and rubble in contemporary China, using material remnants of physical transformations as a heuristic for understanding social change (Chu 2014; Ulfstjerne 2016a; Arboleda 2019). Michael Ulfstjerne, for example, has shown in several studies of Ordos, Inner Mongolia, how the suspension between construction and ruin embodied by the city’s numerous unfinished buildings – a sort of rubble in Gordillo’s parlance – opens space for controversy and contestation, especially when completion is only one possible desirable outcome for different people (2016a, 2016b, 2019). The contention is that if profits accrue to some people through speculation and performances of construction, as opposed to the actual delivery of finished properties, then the end results matter less than we tend to believe. It is possible, he argues, that “value might be generated from not finishing projects” (2016a: 390). This raises an important question about whether incompletion or ruin does, or does not, signal failure and its material manifestation as ruin. It further compels us to think about how representations of ruin often strive to convey a sense of failure and crisis, and how ruin discourse about contemporary development and deindustrialisation is often complicit in a moralising discourse of ruins that allows the observer to ascribe failure to certain places and people. Attending to the unanticipated social significances of rubble, then, brings to light the many unexpected possible meanings attributed to material objects that emerge through interactions with material debris in actually existing physical environments.

In the following passages, I want to lay out how imagery of ghost cities, with the Kangbashi New District in Ordos as a key exemplar but also with reference to other sites labelled as such, operates across different registers of ruin. The new town was at the centre of controversies over ghost cities in China, and depictions of its vast, manicured, but empty landscapes became iconic representations of the phenomenon starting with the first journalistic dispatches.[7] The Kangbashi New District was initiated in 2004 with the goal to become a new urban growth pole in Ordos Municipality and relieve growth pressure on the municipality’s existing major urban centre, Dongsheng.[8] Kangbashi, which assumed the name of a village collective that previously occupied the site, was originally conceived with a 2020 population target of 300,000 people and an area size of 32 km2 (Woodworth 2015). The enormous ambition behind the new town, hyped by local government and business leaders and buttressed by a massive coal-mining boom, helped to inflate a significant bubble in all types of real estate in the new town throughout the initial construction phase after its inauguration in 2006 until about 2010. By then, the new town had densely developed its core section, though few people had settled there. A dip in coal prices the same year, coupled with tightening credit at state-run banks, sent shockwaves through the local economy, severely impacting the real estate sector. It was in this context that Al Jazeera[9] and Time Magazine[10] took notice of Kangbashi and coined the term ghost city to describe its eerily empty state. Photographs of the new town sought to portray its condition of arrested development with dramatic imagery of depopulated cityscapes stretching to the horizon.

These photographic depictions of the new town fit within the pictorial genre of contemporary ruins outlined above. In the following, I present a selection of the most widely circulated images of Kangbashi and other ghost cities and juxtapose these with my own fieldwork images. In the wake of the first reports about Ordos as a ghost city, numerous international and domestic news outlets converged on the site to produce their own dispatches. Professional and amateur photographers similarly began to document the space. As a result, a Google image search reveals hundreds of photographs of Kangbashi under the heading of ghost city produced after 2010. The choice of photos below is therefore selective. Yet they represent, I believe, notable efforts to grapple with the space visually and are emblematic of concern on the part of the image-makers to parse and make claims about what was understood in context as a possible looming economic crisis in China originating in its real estate sector. The photos discussed below show the same new town, Kangbashi, sometimes the exact same sites and subjects, but all produced as parts of differing representational agendas: journalistic, artistic, evidentiary. Of concern here are the ways ruin aesthetics saturate the images and to what ends.

The ghost city in image

Critical studies of photography have long grappled with the slipperiness of the image and its collusions with power. Susan Sontag famously voiced a deep strain of scepticism toward the “violence” of the photographic image, which she attributed to the capacity of the image to conceal and mislead while claiming to reveal (1973). Some years ago, Gillian Rose (2003) brought these concerns to the fore in academic human geography by asking “How, exactly, is geography visual?” Her point was to highlight the frequently unacknowledged power of visual tools, including photographs, in published academic work and teaching. Too many academic practitioners, Rose argued, used photographic imagery in their work without seeming to grapple with the inherent opacity and selectivity of photos. Scholars may be adept at interpreting others’ photographs but appeared to treat their own images uncritically under the mistaken belief that photos used in academic contexts were straightforwardly faithful representations. Rose’s purpose was to encourage a more critical posture toward imagery used in disseminating academic findings. Following this, I ask here: what about photos taken during fieldwork? How are they, as Pétursdóttir and Olsen (2014) suggest, a form of material engagement, rather than merely representation? Their question was raised in the context of ruin photography and debates around so-called ruin porn. Do fieldwork photos of ambiguous ruin sites perform the same critical or ideological work as the formal ruin photograph genre? I illustrate these problems with the following examples.

Example 1: Scale, waste, and ruin

Among the first photos of China’s ghost cities to circulate was a 2010 gallery of images of the Kangbashi New District taken by Michael Christopher Brown for Time Magazine[11] (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Having commissioned the award-winning Magnum agency photojournalist for the project, the publication signalled a desire to produce striking imagery to accompany a report on financial and real estate bubbles in China. By the time the photos were taken in 2010, a vast landscape of new construction was completed. However, while nearly all the housing built to that point in Kangbashi had been purchased, the apartment and villa complexes remained almost entirely empty, as most buyers already possessed homes in nearby Dongsheng and the new town only had few basic amenities. There were, for example, no grocery stores and only a few eateries catering largely to construction workers. The spacious layout of the new town, moreover, assumed usage of a car to move about. As a consequence, during this phase of the new town’s development, the attractively designed vast public spaces and broad boulevards and sidewalks were empty voids at most times, making for striking contrasts with bustling Dongsheng and disorienting bodily experiences for visitors. The scale of the space was especially hostile to pedestrian usage.

Figures 2, 3, and 4. Kangbashi New District, 2010. Credit: Michael Christopher Brown.

Figures 2, 3, and 4. Kangbashi New District, 2010. Credit: Michael Christopher Brown.

These visible features coupled with the brilliant blue sky and expansive arid landscape typical of this section of the southern Gobi Desert made Kangbashi eminently photogenic. What is striking about Brown’s images is the way the physical features of the new town are made a central focus of the photos in order to emphasise the scale of construction and, by association, the enormous waste that it implies. In Brown’s images, the urban landscape extends to distant horizons, with cookie-cutter housing stretching built environments to great distances. Figured in this way and with the new town labelled a ghost city, the construction that is inherent to urban development is freighted not with an anticipation of habitation and growth but with a looming sense of catastrophe and ruination. In this way, the photos bring to light an ambiguity around the documentation of an extant or impending crisis in the local real estate sector.

In my own fieldwork in Kangbashi, which began in 2010 and continued through 2016, I focused on troubles in Ordos’ overheated local real estate sector. Informal financial networks that mobilised capital into local real estate began to unravel around 2010, bringing to a sudden halt most construction projects in Ordos and ending the municipality’s decade-long building boom. In tracking the pause in urban construction, I took scores of photos of projects in the new town and in Dongsheng that were halted. These images show new urban construction through a variety of framings (Figures 5 and 6). My documentary practice involved a substantial amount of walking through areas under construction and taking photos at ground level from vantage points that attempt to capture the entirety of projects.[12] As fieldwork photos, their aesthetic qualities were not paramount. All the same, the physical effort involved in trying to take photos of these sites raised for me at the time the question of the utility of photographic documentation and was a reminder of the perceived necessity to use photography as part of fieldwork data collection activities. What impulse pushed me to take photos of the sites? Would written descriptions in my field notes not suffice to retain strong impressions of the spaces? These questions arose in my own mind partly due to the physical exertion and effort needed to capture the sites in images and the sense that visual data effectively captured something of the essence of the site and moment. At a bare minimum, I would need images for future publication purposes, as demonstrated here.

Figures 5 and 6. Ordos, 2011. Credit: author.

Figures 5 and 6. Ordos, 2011. Credit: author.

Example 2: Emptiness and haunting

As the ghost city phenomenon became more widely reported after 2010, more ghost cities were located around China and images of the sites drew global attention. Along with the immense scale the images of ghost cities conveyed, a feature of the towns repeatedly shown in photos was their eerie emptiness, as though to confirm the ghostly character of these new urban developments. Kai Caemmerer’s photographic series, Unborn Cities,[13] exemplifies this manner of depicting the sites. In his photos, lighting and composition generate a palpable sense of doom in ghost cities. The depicted sites are empty, while buildings appear in the distance through layers of gauzy atmosphere.

Caemmerer’s images of Kangbashi and other ghost cities around China have been displayed in gallery settings and circulated widely online, making them fixtures of the visual phenomenon of ghost cities. Much like Brown’s images, they figure places like Kangbashi and other sites labelled ghost cities as mysteriously abandoned and otherworldly spaces (Figures 7 and 8). Figure 7. No. 21. Credit: Kai Caemmerer.

Figure 7. No. 21. Credit: Kai Caemmerer. Figure 8. No. 7. Credit: Kai Caemmerer.

Figure 8. No. 7. Credit: Kai Caemmerer.

My own images of Kangbashi and the Tianjin Binhai New Area, both new towns labelled ghost cities in news reports and featured in Caemmerer’s series, also show places that are empty, or mostly empty (Figures 9 and 10). There is an undeniable truth to the absence of population that legitimated much of the ghost city trope. Kangbashi, for example, was believed to have less than 10,000 full-time inhabitants in 2010, when sufficient housing had been built for nearly 200,000 people. A similar pattern whereby construction far outpaced new settlement in new towns produced multiple cases featuring similar landscapes of seeming abandonment and emptiness. The tendency among urban administrations to foster quick urban growth in order to reap political and economic benefits powered this surge in growth, fuelled as well by private capital seeking potentially huge profits in China’s burgeoning real estate sector. What I have elsewhere termed China’s “urban speed machine” (Chien and Woodworth 2018) describes a growth coalition for which speed is of the essence.

Figures 9 and 10. Kangbashi New District, 2011. Credit: author.

Figures 9 and 10. Kangbashi New District, 2011. Credit: author.

While urban development is necessarily a spatial and temporal process, the emphasis on rapid growth as a political and economic necessity in China drives urban build-out at a staggering pace. Such speed in urban construction, abetted by a general build-it-and-they-will-come ethos, produces discordant temporalities of settlement. Many places are constructed without drawing significant population for some time, despite properties being purchased as investments. The interim between project completion and settlement leaves urban landscapes that appear at variance with the typical bustle of Chinese cities. The ghost city trope was undergirded by a suspicion that these vast new urban projects would never become populated as planned and that they were, in a sense, already failed. With the benefit of longer hindsight, this has not always been the case however (Yin, Qian, and Zhu 2017). Yet, depictions of the sites rely on generating atmospherics of abandonment in order to ratify the claim of developmental failure.

As speed was a theme in my own research on Ordos and new towns across China, the empty environments captured in fieldwork photos were similar to those shown by Caemmerer, Brown, and other professional and amateur documentarians of ghost cities. In Kangbashi, it was indeed rare to see a pedestrian in the new town’s central square. It is worth noting, however, that my efforts to document new towns by walking were physically exhausting due to the enormous scale of the sites, which heavily militated against any pedestrian activity. Ground-level emptiness of the landscape, in other words, was not just an artefact of the absence of residents but rather a logical aversion expressed to me many times in interviews toward walking the large distances from one’s home to the nearest store, for example. Quite unlike city centres throughout China, where high density and walking are the norm, the built environments of new towns like Kangbashi are predicated on private vehicle usage. The extreme continental climate in Ordos further discourages walking outdoors for any length of time during much of the year. It was therefore unsurprising to see very few people outdoors in the built environment, and the expectation to see people there reflected a norm with little resonance in these places. Ultimately, acknowledging that walking was not how local residents experienced Kangbashi and surrendering to the futility of this data collection practice, I began to survey the spaces by car, thereby allowing myself to view the new environments through a windshield, as others did. Doing so, however, was both expensive and logistically challenging, reducing the perceived benefits of photographic documentation.

Example 3: Disuse and ruin

The third important feature of ghost city photography is its staging of disuse. This feature may seem almost too obvious to mention, but upon closer examination we can see how it is vital to the claim-making of the ghost city notion. Across images of ghost cities that have circulated in the media and online, the central subject of the images is invariably the urban landscape. The scale and emptiness of the sites reinforce the claim that the spaces signify wild overbuilding. Yet, the claim of overbuilding must be qualified. Controversy surrounding ghost cities in the media revolved around the spectre of financial crisis and property market collapse, with ghost cities allegedly serving as leading indicators of broader systemic problems. On the one hand, the massive construction seemed to augur crisis in the property market, as it was noted that the cities had few residents and that purchases of multiple homes in ghost cities were commonplace. The implication was that ghost cities were gigantic speculative bubbles.[14] Others countered that the sale of properties was, in itself, a sign that the property market was functioning as expected and that overbuilding was not a concern if there were always ready buyers of properties. This case has been made about Ordos specifically[15] and, with some qualification, about China’s property markets more generally (Fang et al. 2015). The contention that overbuilding was a subjective judgment refuted by robust sales was a position repeatedly stated to me by local officials and planners in Ordos. In interviews, these same people took umbrage at the term ghost city. The imagery of Kangbashi was especially irritating, they said, as it misrepresented the new town and, perhaps most importantly, was undermining confidence in the property sector.

Photographs of ghost cities do not resolve this controversy. However, they highlight the conflict between exchange value and use value by revealing spectacular instances of disuse. The vast landscapes of ghost cities depicted in imagery like that shown here by the Canada-based scholar-activist Tong Lam (Figures 11 and 12) shows sites that should otherwise contain people but do not.[16] Unlike images of crumbling factories prominent in the contemporary ruin genre, photos of ghost cities show spaces that have yet to be used and, one can presume, will never be used. Purposelessness revealed by the disuse of new space connotes waste and ruin and supplies the critical valence of ghost city imagery. In his image of the enormous central square in Kangbashi and the city hall in the distance (Figure 12), this site of interface between the state and citizenry is rendered as a vast, alienating expanse. The popular assumption that urban space should be inhabited and used is undermined in this imagery and makes for jarring and unsettling visual experiences. In place of city spaces used for the variety of human purposes one can associate with the city, the vast assemblages of new government buildings and apartment buildings in ghost cities seem to serve no function at all, save for being built: they generate capital gains for some and little else – citizens have little to no voice in the making of such a space.

Figures 11 and 12. Kangbashi New District, 2012. Credit: Tong Lam.

Figures 11 and 12. Kangbashi New District, 2012. Credit: Tong Lam.

Figure 13. Kangbashi New District, 2012. Credit: author.

Figure 13. Kangbashi New District, 2012. Credit: author.

Figures 14 and 15. Kangbashi New District, 2014. Credit: author.

Figures 14 and 15. Kangbashi New District, 2014. Credit: author.

What interests me here is the degree to which my fieldwork images of these same sites level the same politicised claims about urbanisation (Figures 13, 14, 15). In the process of conducting fieldwork and critical scholarship, my own focus on urban development revealed contradictions between the use value and exchange value of new homes in sites labelled ghost cities. Nevertheless, the collected images of urban spaces cannot reliably be said to mount claims of this nature. My fieldwork images were not generated as parts of a visual project; instead, they were complements to other data collection steps. What does it say, then, that images produced within these quite different critical agendas depicting the same spaces often do so in the same manner? How does one type of image voice a critical claim and the other merely serves as a neutral observational document?

Conclusion

A central contention of this article is that photographs work in several parallel registers revealed by their intersection with the discourse on ruin. In recent years, theorists have turned to notions of the ruin in order to develop useful heuristics for assessing and interpreting social processes in place (Millington 2013; Gordillo 2014). These new conceptions of ruins originate in a sceptical view of classical ruins and the class-based antiquarian dispositions that have attempted to narrate their meanings. In place of elite practices of ruin-gazing that focus on remnants of antiquity, contemporary ideas of ruin dwell on the mundane and uncelebrated detritus of contemporary life. Yet, not only are both practices shadowed by the impulse to engage in pleasurable melancholy, it must also be noted that ruins of all description, whether new or old, can only exist as a ruin thanks to a socialisation that acculturates viewers to the meanings associated with ruins through a symbolic visual idiom that turns on a creative reengagement with specific sorts of degraded materials.

The claim-making that sits at the heart of ruin-gazing is given an additional layer of mediation in photography. Much as ruins operate only to the extent to which they circulate as part of a culture of ruins, photos of ruins quite explicitly demand forms of active engagement that are themselves culturally delimited. In this sense, there is little distinction between ruins and their photographic representations. Ruins are always and necessarily elements that emerge out of a process of perception, one that is more or less explicitly geared toward claim-making. Whether one shows ruins through textual description or photos, the existence of ruin requires that they be mobilised and somehow shown.

In this article, I have tried to illuminate this point by suggesting that photos of the same places work differently, depending on the critical agenda within which they are mobilised. But I have also questioned how photographic practice during fieldwork differs from the popular genre of ruin photography and its diverse claim-making projects. To address the questions posed at the end of the previous section, the pretence of neutrality in photographic fieldwork documentation is untenable and reveals forms of collusion in the aestheticisation of the research subject that demands careful and forthright acknowledgement. The goal for fieldwork perhaps should not be to produce images that eschew a position on the topic it depicts; photographic subjects cannot be captured in image as objective data. Instead, the approach to fieldwork images might more honestly be in the vein suggested by Pétursdóttir and Olsen (2014) as a type of active engagement with the material world. In this regard, ruin photography and materialist ruin analysis as ethnographic practices are aligned as modes of critical claim-making through engagements with various material. The forces at work remaking China’s cities are invariably opaque and dispersed. Ruins, and ironically photographs thereof, can serve, as this article suggests, as a medium through which to reveal some of these processes by drawing together audiences, however narrow, and constructing the meanings of space actively in and through images and their exchange.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the following sources of financial support for research contributing to this article: Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange Faculty Research Grant and the Regional Studies Association Early Career Grant. The author would like to thank the editors of the special issue and anonymous reviewers whose comments helped improved drafts of this article. Thanks are also due to Michael Christopher Brown, Kai Caemmerer, and Tong Lam for use of their images. Any shortcomings of the final draft are attributable to the author alone.

Max D. Woodworth is Associate Professor of geography at Ohio State University. 1148 Derby Hall, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, 43210, United States (woodworth.42@osu.edu).

Manuscript received on 16 February 2021. Accepted on 10 June 2021.

Primary Sources

Exhibition

JENKINS, William (curator). 1975. “The New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape.” International Museum of Photography. Rochester, New York. October 1975 – February 1976.

Documentary film

BAICHWAL, Jennifer. 2006. Manufactured Landscapes. New York: Zeitgeist Films. 90 min.

Photo collection books

BURTYNSKY, Edward. 2005. China. Göttingen: Steidl.

LAM, Tong. 2013. Abandoned Futures: A Journey to the Posthuman World. London: Carpet Bombing Culture.

MARCHAND, Yves, and Romain MEFFRE. 2010. The Ruins of Detroit. Göttingen: Steidl.

Online image galleries

BROWN, Michael Christopher. 2010. “Ordos China: A Modern Ghost Town.” http://content.time.com/time/photogallery/0,29307,1975397,00.html (accessed on 23 October 2021).

CAEMMERER, Kai. “Unborn Cities.” https://kaimichael.com/unborn-cities (accessed on 23 October 2021).

LAM, Tong. http://visual.tonglam.com/ (accessed on 23 October 2021).

References

ARBOLEDA, Pablo. 2019. “Reimagining Unfinished Architectures: Ruin Perspectives between Art and Heritage.” Cultural Geographies 26(2): 227-44.

CHIEN, Shiuh-shen, and Max D. WOODWORTH. 2018. “China’s Urban Speed Machine: The Politics of Speed and Time in a Period of Rapid Urban Growth.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42(4): 723-37.

CHU, Julie Y. 2014. “When Infrastructures Attack: The Workings of Disrepair in China.” American Ethnologist 41(2): 351-67.

CRANG, Mike. 2003 “Qualitative Methods: Touchy, Feely, Look-see?” Progress in Human Geography 27(4): 494-504.

DESILVEY, Caitlin, and Tim EDENSOR. 2013. “Reckoning with Ruins.” Progress in Human Geography 37(4): 465-85.

FANG, Hanming, Quanlin GU, Xiong WEI, and Li-an ZHOU. 2015. “Demystifying the Chinese Housing Boom.” Working Paper 21112, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2015. https://www.nber.org/papers/w21112 (accessed on 23 October 2021).

GORDILLO, Gastón R. 2014. Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction. Durham: Duke University Press.

HSING, You-tien. 2009. “Urban Housing Mobilizations.” In You-tien HSING, and Ching Kwan LEE (eds.), Reclaiming Chinese Society: The New Social Activism. London: Routledge. 17-41.

——. 2010. The Great Urban Transformation: Politics of Land and Property in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

JONES, Andrew F. 2010. “Portable Monuments: Architectural Photography and the ‘Forms’ of Empire in Modern China.” Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 18(3): 599-631.

KITCHIN, Rob, Cian O’CALLAGHAN, and Justin GLEESON. 2014. “The New Ruins of Ireland? Unfinished Estates in the Post‐Celtic Tiger Era.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38(3): 1069-80.

KORCHECK, Kathy. 2015. “Speculative Ruins: Photographic Interrogations of the Spanish Economic Crisis.” Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies 19(1): 91-110.

LYONS, Siobhan (ed.). 2018. Ruin Porn and the Obsession with Decay. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

MACAULAY, Rose. 1953. The Pleasure of Ruins. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

MILLINGTON, Nate. 2013. “Post-industrial Imaginaries: Nature, Representation, and Ruin in Detroit, Michigan.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37(1): 279-96.

ORTELLS-NICOLAU, Xavier. 2017. “Raised into Ruins: Transforming Debris in Contemporary Photography from China.” Frontiers of Literary Studies in China 11(2): 263-97.

PÉTURSDÓTTIR, Þóra, and Bjørnar OLSEN. 2014. “Imaging Modern Decay: The Aesthetics of Ruin Photography.” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 1(1): 7-23.

ROSE, Gillian. 2003. “On the Need to Ask How, Exactly, is Geography ‘Visual’?” Antipode 35(2): 212-21.

SHAO, Qin. 2013. Shanghai Gone: Domicide and Defiance in a Chinese Megacity. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

SHEPARD, Wade. 2015. Ghost Cities of China: The Story of Cities without People in the World's Most Populated Country. London: Zed Books.

SHIN, Hyun Bang. 2016. “Economic Transition and Speculative Urbanisation in China: Gentrification versus Dispossession.” Urban Studies 53(3): 471-89.

SIMMEL, Georg. 1965. “The Ruin.” In Kurt WOLFF (ed.), Essays on Sociology, Philosophy and Aesthetics. New York: Harper & Row. 259-66.

SMITHSON, Robert. 2011. “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey.” In Brian DILLON (ed.), Ruins. Cambridge: MIT Press. 46-51.

SONTAG, Susan. 1973. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux.

SORACE, Christian, and William HURST. 2016. “China’s Phantom Urbanisation and the Pathology of Ghost Cities.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46(2): 304-22.

STOLER, Ann Laura. 2008. “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination.” Cultural Anthropology 23(2): 191-219.

—— (ed.). 2013. Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination. Durham: Duke University Press.

ULFSTJERNE, Michael A. 2016a. “Unfinishing Buildings.” In Mikkel BILLE, and Flohr SØRENSON (eds.), Elements of Architecture. London: Routledge. 405-23.

——. 2016b. “The Artyficial Paradise: Municipal Face-work in a Chinese Boomtown.” In Michael KEANE (ed.), Handbook of Cultural and Creative Industries in China. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. 80-96.

——. 2019. “Iron Bubbles: Exploring Optimism in China’s Modern Ghost Cities.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 9(3): 579-95.

VERGARA, Camilo José. 1999. American Ruins. New York: Monacelli Press.

WANG, Meiqin. 2015. Urbanization and Contemporary Chinese Art. London: Routledge.

WOODWORTH, Max D. 2015. “Ordos Municipality: A Market-era Resource Boomtown.” Cities 43: 115-32.

——. 2020. “Picturing Urban China in Ruin: ‘Ghost City’ Photography and Speculative Urbanization.” GeoHumanities 6(2): 233-51.

WOODWORTH, Max D., and Jeremy L. WALLACE. 2017. “Seeing Ghosts: Parsing China’s ‘Ghost City’ Controversy.” Urban Geography 38(8): 1270-81.

WU, Hung. 2012. A Story of Ruins: Presence and Absence in Chinese Art and Visual Culture. London: Reaktion Books.

WU, Fulong. 2015. Planning for Growth: Urban and Regional Planning in China. London: Routledge.

YIN, Duo, Junxi QIAN, and Hong ZHU. 2017. “Living in the ‘Ghost City’: Media Discourses and the Negotiation of Home in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, China.” Sustainability 9(11): 2029-43.

[1] See, for example, Bill Powell, “Inside China’s Run-away Building Boom,” TIME, 5 April 2010, http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,1975336,00.html (accessed on 25 October 2021).

[2] See Rebecca Solnit, “Detroit Arcadia: Exploring the Post-American Landscape,” Harper’s Magazine, July 2007, https://harpers.org/archive/2007/07/detroit-arcadia/ (accessed on 23 October 2021); John Patrick Leary, “Detroitism. What Does ‘Ruin Porn’ Tell Us about the Motor City?,” Guernica: A Magazine of Art and Politics, 15 January 2011, https://www.guernicamag.com/leary_1_15_11/ (accessed on 4 February 2021). Also see Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, The Ruins of Detroit, 2010, Göttingen: Steidl; Tong Lam, Abandoned Futures: A Journey to the Posthuman World, 2013, London: Carpet Bombing Culture. A list of all cited artworks is provided at the end of the article.

[3] William Jenkins (curator), “The New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape,” October 1975 – February 1976, International Museum of Photography, Rochester, New York.

[4] Lauren G. Higbee, “Reinventing the Genre: New Topographics and the Landscape.” Paper presented for a class on History of Photography at Columbia College, 12 December 2011, https://www.academia.edu/1947419/Reinventing_the_Genre_New_Topographics_and_the_Landscape (accessed on 23 October 2021).

[5] Edward Burtynsky, China, 2005, Göttingen: Steidl.

[6]Jennifer Baichwal, Manufactured Landscapes, 2006, New York: Zeitgeist Films.

[7] Melissa Chan, “China’s Empty City,” Al Jazeera, 10 November 2009, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/asia-pacific/2009/11/2009111061722672521.html (accessed on 4 February 2021); Bill Powell, “Inside China’s Run-away Building Boom,” op cit.

[8] There is, in fact, no town named Ordos, which is an ancient name for the region contained by the giant northern loop of the Yellow River and the Great Wall.

[9] Melissa Chan, “China’s Empty City,” op cit.

[10] Bill Powell, “Inside China’s Run-away Building Boom,” op cit.

[11] Michael Christopher Brown, “Ordos, China: A Modern Ghost Town,” TIME, 25 March 2010, http://content.time.com/time/photogallery/0,29307,1975397_2094492,00.html (accessed on 23 October 2021).

[12] A limitation of my photo-taking efforts was the fact that I did not possess a wide-angle lens to easily encompass whole projects, which tend to occupy massive tracts of land. Consequently, I needed to retreat some distance in order to capture sites in the frame, and as a result the images include quite massive panoramic scenes of halted construction. Using my 35mm point-and-shoot camera, a result is that the buildings in my photos appear quite distant and small and achieve nothing of the monumental quality of Brown’s images.

[13] Kai Caemmerer, “Unborn Cities,” https://kaimichael.com/unborn-cities (accessed on 23 October 2021).

[14] Bill Powell, “Inside China’s Run-away Building Boom,” op. cit.

[15] Patrick Chovanec, “Insight on Ordos,” An American Perspective From China, 13 May 2010, https://chovanec.wordpress.com/2010/05/13/insight-on-ordos/ (accessed on 25 October 2021).

[16] For more photos, see Tong Lam, http://visual.tonglam.com/ (accessed on 23 October 2021).