BOOK REVIEWS

In the Midst of Rubble, Bordering the Wasteland: Landscapes of Ruins and Childhood Experiences in China

Introduction – Following Chinese children far from urban centres: The trail of ruins

There exist many areas in China today characterised by their decaying buildings, at one and the same time the underside and corollary of the gigantic urban building site that is transforming the country (Audin 2017). This article sets out to explore these landscapes of ruins through the links that the children who experience them in their daily lives forge with them. We are mainly acquainted with the tribulations of Chinese only children, the “little emperors” (Chicharro 2010) about whom much has been written but who are essentially city children, since the law was very soon made more flexible for rural areas. The ruins, which are not all in the countryside, far from it, but which are almost all at a distance from the urban centres in one way or another, have led us to pay attention to other varieties of childhood in China.

In fact, the childhoods dealt with here have already attracted a great deal of attention from the Chinese social sciences, but in a generally negative way. These are the children of “migrant workers” (nongmingong zinü 農民工子女) and children “left behind” in the countryside (liushou ertong 留守兒童). The former, accompanying their parents who have come to seek work in the city, cannot attend the public schools financed by the local authorities (Froissart 2003), although the situation has evolved in small cities. In Chinese literature specialising in the subject, produced by psychologists and specialists in the sciences of education, these children are, in addition, supposedly victims of a poor upbringing by their families and suffer from severe psychological problems linked to low self-esteem (zibeigan 自卑感, a keyword in this type of literature) (Shen 2007). The psychological portrait painted of the second category of children does not fundamentally differ from the first: suffering from the absence of their parents, left with uneducated grandparents and attending backward rural schools, they are said to develop all manner of “deviant behaviour” (Duan et al. 2013). These problems, disseminated in the Chinese media and around which a great consensus exists, are familiar to most educated Chinese. Where a social sciences pluralist vision would seem to call for a variety of accounts and representations, the scientific approaches I have been able to study so far on these children seem on the contrary to be unequivocal. It is also prescriptive, leaving little room for a reflexive position where the researcher’s values and norms are the first to be questioned. Lastly, it is top-down – the same questions appearing each year in the funding orientations of Chinese research – and as a result, locked into the same issues. As we can see, it is not so much the categories of debate that are open to question here, like they do in the work of “deconstruction,” as the modes of determination used, that is, the logic by which certain characteristics are attributed to these categories. Psychological and educational problems are associated with specific populations (children of migrants and rural children), which are defined by political categories (“nongmingong zinü” and “liushou ertong”) and inscribed within a fixed geography (the country and peripheries of cities where the migrants have settled): everything is already in place, the debate seems to be closed in advance.

The aim of this article is not to study in detail this closure of the debate – which depends as much on the particularity of the children’s social position, scarcely able to utter a discordant word, as on the limits of pluralism in social sciences in China and on current globalised models of research funding – but rather to open it out by taking the experiences of these children as a starting point in a bottom-up approach. Stepping aside to observe what interests the children themselves, and follow them in their wanderings, instead of starting with the educational problems that we – the adults who worry about them – perceive, allows the emergence of the parts of their experience that cannot find a place in the current discourse. The ruins offer a privileged entry point for this project that is both modest – it cannot be more than a side entrance into these childhoods and cannot paint a complete picture – and ambitious, since it is the very modalities of the discourse on these children that are being questioned. What do these ruins mean for the children? What type of “affordances” (Gibson 2014), that is, what tangible possibilities do they offer? What do they allow, what constraints do they exercise, what quality of experience do they accompany? And conversely, what does the nearby presence of children, or lack of same, mean for these landscapes? It is a question of revealing the variable architectures of the links that humans forge with the places they inhabit or leave, and which create very different environments for the children.

This research is based on two ethnographic surveys, each of which highlights these differences in environment. The first was in Shanghai, in a dilapidated industrial neighbourhood between 2006 and 2008 before the complete renovation of the neighbourhood. It was inhabited solely by nongmingong, sometimes hired on the spot to demolish the old buildings where the families themselves lived. To gain access to the site and to be identifiable by the children and their parents, I was their English teacher in a poor-quality private school, where I also lived for a term. I gave private lessons in some families as well. The second survey was carried out amongst country children in a town (zhen 鎮) in the mountains of Guangdong Province, about two hours from Meizhou, the city (shi 市) on which this town depended. The town had just over 20,000 inhabitants, but most of the young people, here as elsewhere, had left to look for work in the city. The town’s primary school was attended by around 700 children from surrounding villages that had previously had their own schools. I was an English teacher there for four months, from September to December 2019. The gap of ten years between the two surveys can be explained by the difficulties inherent in accessing this type of area for fieldwork in China but does not detract from the demonstration. Whilst not timeless nor covered by the Chinese media’s topical events, it is part of fundamental demographic, educational, and social trends that slowly evolve and, in fact, have become increasingly pronounced over the last ten years. In both sites, the children of the primary school where I taught are the privileged protagonists of the survey.

This approach intends to be distinctive both in its theoretical tools and in its methodological particularities (first section). A dynamic of concentration will then be studied (second section) followed by a dynamic of dispersion (third section), in which the children’s relationships with the very different ruins that surround them are bound up. In conclusion, I will return briefly to the limits of the current modes of determination in the scientific discourse regarding these children and the conditions under which an opening up may be possible, issuing notably from the fields of geography and demography.

Theory and method: Determinations, structural dynamics, and ethnography of the children’s independent journeys

The issues raised in this article were inspired by Gilles Deleuze. It is a question not of understanding “the” environment of migrants or “the” rural environment but an environment that the children explore or pass through at a given moment, and some of the environments into which they find themselves plunged one after the other – with the indefinite article serving as a first prompt in moving towards another way of considering the question of determination (Deleuze 1993: 81). The expression of this question in social science terms involves both finding theoretical landmarks within these traditions that leave room for this plurality and using a methodology that can reproduce this exploration empirically. The scene that follows makes my position on these two points clear. It takes place during the Shanghai fieldwork, in the very dilapidated neighbourhood in the process of being demolished, and where only migrants live. The year is 2008, shortly after the particularly deadly earthquake of 12 May that shook Sichuan, of which images of devastation were played continuously on Chinese television. I had just given an English lesson to Ni Zheng, who was in the fifth year of primary school. It was already dark outside:

Stroll through the neighbourhood in the evening after the lesson – Ni Zheng insists on accompanying me back to the bus station, a quarter of an hour away. He spontaneously suggests we enter the area of wasteland, taking us a little out of our way. As we walk through the very heart of the demolition zone, he remarks: “Here is like Sichuan after the earthquake.” We go to the house of one of his friends, another pupil from the old school, but it is also the place where he used to live before – as we are climbing a little staircase to enter his neighbours’ room which is upstairs, he says, “My house was there,” pointing out a place right next to it that had been destroyed. Then he pushes open the door, hesitantly nonetheless, at the same time as he glances inside and announces his arrival. The mother is getting ready to wash her son and they are watching TV. The mother greets me very graciously, and when Ni Zheng tells her I give him lessons, she asks me if I live nearby. (…) I’m on my way, out of politeness Ni Zheng asks me if I can find my way. I leave, all three come out onto the doorstep to say goodbye before going back in to watch TV. (Field notes, Friday 6 June 2008)[1]

Three fundamental acts in the way children organise their “spatial practices” (de Certeau 1980) emerge from this scene, three acts that exist in varying degrees in other analogous scenes and that I will take account of here without, however, placing them on the same level or bestowing the same importance upon them. The first act is positioning oneself: it occurs when Ni Zheng places his own living environment in relation to that of Sichuan in a brief comparison. The second consists of directing oneself within the immediate environment: this occurs when the child chooses to change our route, based on his former landmarks (“my house was there”). The third consists in finally accommodating oneself to an environment, with the constraints that it implies and what it allows: accommodating my presence, for example, coping with the absence of his former house, taking advantage of the presence of another family that he knows, etc.

Yet, these three acts each throw down a bridge towards different forms of determination. When the child positions themselves within a fixed frame of reference, their act is superimposed upon that of an outside authority positioning them in that they are in such a region rather than another, in the city or in the countryside, in such an environment, such a type of family, etc. It represents an opening for reflection on determination in the classic sense of the term (an individual is determined by their position on a geographic or social map). When the child directs themselves within their immediate environment, on the other hand, when they give a direction, follow their own wishes, pursues their objectives, it is less a question of external determination than self-determination. Lastly, the act of accommodation reveals a third register that is neither that of external determination nor that of self-determination, but that of a form of reciprocal, multiple determination between the children and their environment. It is this that I would like to follow in more detail here. However, the three acts and the three registers of determination identified here are all essential. Therefore, the theoretical framework I suggest here takes into account, in its way, the question of external determination through a structural stance (i). The methodological approach, for its part, integrates the determination that children can demonstrate if one let themselves be guided by them (ii).

(i) How one can express, in theoretical terms, the differentiated experiences of the ruins by the children? The landscape of rubble and demolished houses around us was not the result, unlike Sichuan, of a natural disaster that had happened in the present. It was the result of a sharing of the urban space, in which certain individuals saw themselves relegated to housing in residual spaces unwanted by others. The position of some is thus linked to that of the others: this is a question of structural geography, the name of a theoretical current I am drawing on here (Desmarais 2001), which follows two axes. The first concerns the political control that shapes the trajectories of individuals: in simple terms, certain people can decide on the arrival point of their trajectory (referred to as “endoregulated”). These are the “selective nomads” who converge towards what might be called elective spaces, the urban hyper-centres where everyone wants to live. Others, “sedentary persons” and “residual nomads,” are forced to live in abandoned and denigrated spaces (“exoregulated” trajectories) such as rural areas or the type of urban peripheries we are concerned with here – with a spectrum of circumstances ranging from one extreme to the other. This political line, originally developed in historical geography research in France and Canada (Desmarais and Ritchot 2000), can be applied very easily to contemporary China, with its system of administrative registration (hukou 戶口) that differentiates individuals by classing them as “rural” or “urban,” and under which their social benefits are dependent upon their place of origin, a system that is no less important today.

The second axis regards the collective form of these trajectories, which are “polarising” (when many trajectories converge on regions or places) or “diffusing” (when, on the contrary, the trajectories of individuals lead them to draw apart from one another, creating a dynamic of living together completely different).

Table 1. Desmarais’ four settlement dynamics (2001)

| Trajectories... | ... endoregulated | ... exoregulated |

| ... polarising | Gathering | Concentration |

| ... diffusing | Escape | Dispersion |

The third column especially applies to the fieldworks here.

The two dynamics of concentration (exoregulation and polarising) and dispersion (exoregulation and diffusing) thus give the framework through which one can understand the different types of ruins the children encounter. This framework makes it possible to consider structural logic that is not in play here and now, without, however, being determinist and fixed.

(ii) This geography of childhood is here based on innovative material: the ethnographic account rather than the map, completed here by photographs. The children knew me as a teacher and a neighbour and were usually happy to see me, to chat, and sometimes to have me take part in their games. In my work of participatory observation, there were privileged moments such as the one I have described with Ni Zheng that emerged during independent outdoor journeys and would seem to be a real little research protocol in themselves. Sometimes I accompanied the children when they already had a destination in mind, while at other times I asked them to show me round the neighbourhood, but in every case, I endeavoured to allow myself to be guided by them. Even though my presence obviously influenced the events that followed, these scenes nonetheless reveal the interests, the repertoires of actions, and the landmarks of the children themselves. The subjects of focus, the concern to leave the initiative to the children, amount to taking account of what Anglophone childhood studies call the children’s agency, and which is one of the main contributions claimed by this movement (Bühler-Niederberger 2010). Although the insistence on attributing agency to the children sometimes takes on an ideological turn (Lancy 2012), this school of thought has nonetheless radically transformed the way in which the relationship of children to surveys is seen in the social sciences, including the methodology. In this case, following the children’s unrestricted outdoor wanderings is a particular example of this tendency, suited to fieldworks where children are often outdoors, with greater freedom and less homework or extracurricular activities than other children in China, and consequently a more obvious participation in public life (Breviglieri 2014).

Concentration and dilapidated habitat: Organising space under collective pressure

Concentration designates the areas of relegation where many migratory trajectories converge, most often linked to economic imbalances. They are the trajectories of “residual nomads” who settle where they can. These dynamics can be found, mutatis mutandis, everywhere in the world and in different forms: slums, migrant camps, rundown suburbs in France, or the downtowns in the United States. In China, the urbanisation goes along with the multiplication of offset areas, threshold areas, and enclosed spaces where subsist the remains of former villages, workshops, warehouses, or wasteland from previous eras. In Shanghai, these spaces are deemed the “intermediary zones between the city and the country” (chengxiang jiehebu 城鄉結合部). Enclaves where newly arrived migrants can lead a “life amidst rubble” (Richaud and Amin 2020), at least temporarily, are therefore becoming more numerous. With its buildings inherited from the workshops and warehouses of the industrial period that can be found in many of the modern landscapes of ruins (Mah 2012), its half-demolished houses, the frequent passage of lorries, the dust, the noise from the nearby ring road, and the building sites on all sides that represent the horizon line and punctuate the removals, the neighbourhood where I conducted my research provided a striking example of this type of environment.

Figure 1. A child shows some fruit, which he has just picked up in a neighbouring garden, to his mother, who is cooking at the doorstep on the second floor of a temporary house. Credit: author.

Figure 1. A child shows some fruit, which he has just picked up in a neighbouring garden, to his mother, who is cooking at the doorstep on the second floor of a temporary house. Credit: author.

The following scene is centred on Ni Zheng’s classmate Mao Feng, to whom I also gave English lessons:

As I am approaching his home to give him a lesson at around 5:20 p.m., I encounter Mao Feng who is going in the opposite direction without seeing me. He is holding two badminton rackets and nibbling a stick of sugar cane. I call out to him, he replies that he will be back in half an hour, I ask him if I can come with him. Interesting walk across the whole neighbourhood in an area that I hardly know, where another school for migrants had been demolished more than a year ago. What strikes me is, on the one hand, the greater number of children playing there, and on the other hand, the extent of the destruction, with particularly impressive landscapes. Yet, order seems nonetheless to exist in this chaos for Mao Feng, who stops twice in small shops to buy an ice cream and a shuttlecock. Finally, we arrive in front of a large door in rusty metal – he shouts out to call a classmate who lives upstairs, but who is clearly absent. After ten minutes, we set off in the opposite direction. During the entire trip, he encounters classmates who call out to him; he also encounters a neighbour who asks him what he is doing (in a strict voice, but which does not alarm Mao Feng for one second), and an aunt. Once home, the mother tells me I can give my lesson after eating and encourages me to “play” (wan 玩) a little with Mao Feng in the meantime. But he has already settled down in the backroom to watch a film. (Field notes, Friday 21 March 2008)

Where my stranger’s eyes only see chaos, order emerges via Mao Feng’s journey, demonstrated by the great sense of ease shown by the child throughout it. It is an order performed in several acts: the organisation of the familiar environment is reasserted by a set of actions that punctuate our progress, through little supports – rackets, purchases, sweets – and familiar landmarks – the shops, his aunt’s house, his friend’s. It is also a collective order, directly involving other players: the school friends who call out to him and exchange a few words along the way, reaffirming a form of mutual acquaintance and raising the possibility of games; the adults – the aunt, the neighbour, and the researcher-teacher – who, at the same time as they provide support, also exercise repeated micro-control, thereby supervising the child’s walk. This is the essential characteristic of the environment of concentration: daily activities are carried out under the pressure exercised by the presence of others. Even in the final moments of the scene, the moment of withdrawal when Mao Feng is watching a film, the others are never far away since he is in the backroom that serves as a cybercafé, equipped with several computers where people come and go, and in addition, his mother expects him to look after the guest in some way.

In this respect, the dilapidated buildings that characterise the neighbourhood represent both proximity to others through the porosity of boundaries, and repeated attacks on the strength and durability of separations, evident in the cracks, the damage, and collapse visible almost everywhere; and the constant erosion – the rubble and rubbish – that takes over the common space. The outdoor environment was thus marked by the dust, pollution from lorries, rubble, and various pieces of debris. This environment seems to correspond to the image of dirt long associated with migrants, despite the efforts of researchers to denounce this stigma (Davin 1996; Florence 2006), that the players, great and small, must accommodate (Zhou 2016; Wu and Zhang 2019). There is, however, a logic of fold (“pli,” Deleuze 1988) at work in which the interior is organised on and against the exterior, and which serves to protect oneself from this harmful environment. School, for example, is a pleat (“repli”), weakened by attempts to encroach on its space by all those who do not belong to the world of education (Salgues 2012b: 135-6), but which allows order to be imposed on the outside. The following scene that took place during “Childhood Day” (celebrated on 1 June in China) highlights this collective dimension through the management of cleanliness:

Celebratory atmosphere in the primary school: an extremely cheap ice-cream is given to all the children. I go and take a look at the fifth years: the tables have been organised to form a square, leaving a big space in the middle, where a large heap of rubbish, ice-cream wrappers, sunflower seed shells and so forth, is accumulating – at the end of the day the children will sweep the dirt floor, and everything will have been cleaned up. In the sixth-year classroom the tables are organised in the same way but without the rubbish: in the middle of the room, a group of pupils, girls, are putting on a show. (Field notes, Thursday 1 June 2006)

The clean and the dirty are the subject of an agreement in situ here – this is different from an external norm that might disqualify the individuals, as when the school is subject to health checks by the local authorities, who might conclude by citing these problems to justify closing the school. The agreement is not either just a simple habitus applied mechanically by individuals: there might be a rural habitus transmitted by the parents, but at least it has been reactivated in accordance with the agreement that has been arrived at – the way to manage things changes in the class next door. The perimeter of this agreement may vary and these folds and pleats be repeated at other levels: the street as a fold, for example, when space and traffic allow. Hair-washing, washing children in the street in basins, bears witness to an agreement on what can be shown as well as on the way to manage what the body produces as waste, such as dirty water, etc. Water, in fact, plays an essential role in the common concern for hygiene, both because access to it is common (an outside tap supplies several houses; there are also sellers of boiled water), and because it is the water used for washing or cooking meals that will then be thrown out to carry away the waste thrown on the ground. The limits of the common agreement are therefore the limits of the environment in which the child finds themselves at any given moment, the former vary along with the latter: the ring road, after which starts an urban neighbourhood that corresponds more closely to Shanghai’s cleanliness norms, or where the wastelands that mark the edges of the space where migrants are concentrated, represent the frontiers between different milieus governed by different agreements, but between which the children constantly navigate.[2]

Figure 2. Some women gather at a water point. In front of her house, a girl in primary school does her homework. Credit: author.

Figure 2. Some women gather at a water point. In front of her house, a girl in primary school does her homework. Credit: author.

The architecture of life in common in these living spaces marked by concentration is not solely vertical in a logic of folds and pleats. It is also horizontal, gradually transforming surrounding people into neighbours whose presence is truly felt in this closely packed environment. In these conditions, a household will organise the sharing of its space in a way that does not exclude the other from an intimacy that has been barely invested in these temporary lodgings, but on the contrary, always maintains an open door to them (literally). Against a background of constant comings and goings, the need to create a place for everyone in addition to a network that spreads out across the neighbourhood and beyond the family, place of origin or province, is a concrete implementation of the “right to the city” (Harvey 2008), of which Ling Minhua (2019: 199) recalls the importance when considering the integration of young nongmingong in Shanghai. Amongst the children, ethnography thus highlights many everyday acts of hospitality that demonstrate this concern. The two scenes described above with Ni Zheng and Mao Feng end with a moment of hospitality. On both occasions, the child deferred to an adult woman to welcome me. Therefore, in this case hospitality was shared between ages and genders. At the same time, there is a common repertoire that the children learn to master very early: every pupil, if they saw me in the street, suggested I come to sit down in their house, even in the absence of an adult – and would pour me some hot water and a little tea if they had any, and offered me some sunflower seeds. This is certainly an ordinary everyday gesture, even though in this case it is highlighted by the extraordinary presence of a foreigner – but it is a characteristic of the position of ethnographers doing a distant fieldwork, to raise, by their very presence, the question of the forms that hospitality takes in the places they are invited (Stavo-Debauge 2017: 12).

We can compare the political architecture that emerges from this picture to that of a different type of Chinese childhood, that of “gathering,” of which the ideal type is the only child under permanent pressure to succeed at school and living in the high tower blocks of a much-coveted neighbourhood – although the situation of most urban Chinese children lies in a hybrid arrangement somewhere between the two extremes. In the migrant neighbourhood, everyone was simply renting or even occupying at no charge, sometimes for a very short period, a dwelling that is often summarily converted from former dilapidated industrial premises. Conversely, space in neighbourhoods where property prices are soaring is thought of from the outset as private property. This difference cannot but be essential. The “right to the city” previously mentioned is indeed fundamentally incompatible with the right to private property. The former considers that space should primarily be organised and arranged for everyone; the second, on the other hand, has as its starting point the appropriation of a place by an individual. There is conspicuous order in gathering spaces, order that is paid for in hard cash (street cleaning by professionals, landscaping of the gardens in private homes) and where external norms take precedence over the agreement in situ. In these urban centres, the very organisation of the space increases the number of partitions (moreover, apartments in China have two superimposed front doors) and maps out divisions in the very configuration of the apartments, and even before they are occupied by a family. For the children concerned, this signifies a world mainly organised away from the public eye, with grandparents playing an important role in anchoring their activity within the family home. There is obviously no longer any question of everyday gestures of hospitality in this context. The “bedroom culture” (Glevarec 2009) described by childhood and youth anthropologists in European and American fieldworks is therefore occupying an increasingly large place today in “gathering China.” This goes hand in hand with a great interest – valuing and concern – for the inner life of the child, displaying a modern childhood concern for psychologists. It is this concern that we find in the literature on the children of nongmingong, where their “inferiority complexes” are analysed in detail.

In my fieldwork, however, even when the children had their own bedroom – which was sometimes the case in the families I followed, depending on where they moved – they did not invest in them, leaving them completely empty. Living amid the rubble of a neighbourhood that is in the process of demolition does not mean that they crave urban order and private spaces that tend to shape lives of children at this age in the newer allotments and more privileged strata. Instead, it means another architecture of life in common where the permanent presence of many other people is one of the main affordances – inseparably both resource and constraint. At the same time as it differs from the gathering dynamics of the city-centres, this dynamic of concentration also differs from that of dispersion, which gives rise to the exploration of very different milieus.

Dispersion and abandoned places: The unpredictable marches in childhood experiences

Dispersion reveals less occupied, commonly empty spaces where the ruins are characterised by abandonment rather than by temporary occupation. The Chinese countryside frequently presents this type of landscape. In the rural fieldwork in the mountains near Meizhou, there is plenty of space (as testified by the many new houses, paid for by those who have left, always very spacious and three-quarters empty, even when occupied). The pace of life is slow (together with the quality of the air, this is the first thing mentioned by the inhabitants when vaunting the qualities of their environment) and there are mountains everywhere, synonymous with a certain degree of isolation. In demographic terms, it is children and above all elderly people who are the most numerous, since adults of working age have mostly left for the city. Here, the abandoned buildings are often houses or schools. The former can serve as storage places – this is the case with the collective houses of the Hakka people who live there, the tulou (土樓) dwellings famous in nearby Fujian but which have not enjoyed the same success among tourists here. The latter remain the scene of various activities: playgrounds for children, places to hang out washing, or where elderly adults meet to chat and play cards, in a context where time, which is not monetised, or very little, is plentiful. These landscapes of ruins therefore seem profoundly “aged”: shaped by the question of age, as in other contexts a question might be described as profoundly gendered.

However, even the rural areas should be considered dynamically. To see in them merely a logic of dispersion is understandable when viewed from the cities, but the children’s experience cannot be interpreted unilaterally from this distant point of view. The following scene took place one Saturday morning when I went out into the centre of the town:

I come across Yuanyuan, a third-year pupil. She was going to her grandparents’ house, but they were sleeping. We stroll about together, talking all the while. She takes me to the edge of the town, to a friend’s house who is not there, then in a completely different direction, to look for another friend. These are very old houses, we could be in a village; moreover, at my request we make a detour at one point through a little village on the edge of town. Yuanyuan complains that her slippers (she is wearing slippers!) are not suitable, that they will get dirty, and in fact they are getting wet. At one point, between the earth houses, she loudly remarks whilst holding her nose that there is a bad smell: from a local point of view, she really is a little “city-dweller.” We meet nobody. We also go through a little square equipped with play apparatus for children. Its situation on the periphery is significant – apart from us there are two small children driven there by their father on his motorbike.

We have some tea at her friend’s house. The mother is there as well as her elder brother who is in his second year of middle school. The mother explains that their laojia [老家, village of origin where each family possesses some land by right] is in the mountains, but that they rent this house so that the children are near their school. The rent is 50 yuan a month [less than 7 euros]. I ask what they have planned for their son when he finishes middle school. She answers me somewhat indirectly, telling me that he will certainly not be able to attend the big county (xian 縣,) high school. “If he studies in middle school, it’s better that he goes on to high school,” she says, but “we’ll have to see if he wants to or not; if he doesn’t like studying, there’s no point.” (Field notes, Saturday 14 December 2019)

We are in a town (zhen) that belongs to the world of rural China from an administrative point of view. Yet, this fixed, administrative cartography does not correspond to the children’s everyday experience, still relative, of a lively, familiar centre and empty, potentially unsettling peripheries. For Yuanyuan, who lives in the town centre, her perceived configuration of the village where we make a detour (the mud, the smells, the absence of familiar landmarks) seems hostile, far from the more urban places where collective activities are concentrated – my casual remark about her “city-dweller” side in relation to the situation is completely justified. For her friend’s mother, on the other hand, a house on the edge of a rural town that other people no longer want (and rented for almost nothing, even in the eyes of the locals) represents a move towards a more urban centre. However, the education of her son, if he wants and can continue it in high school (which is not compulsory after middle school and requires passing an exam), would suddenly reposition them in a different cartography, sending them back to their rural position far from the county’s administrative centre (xiancheng 縣城). The final remark reported in the extract leads one to suppose that she would not willingly envisage this.

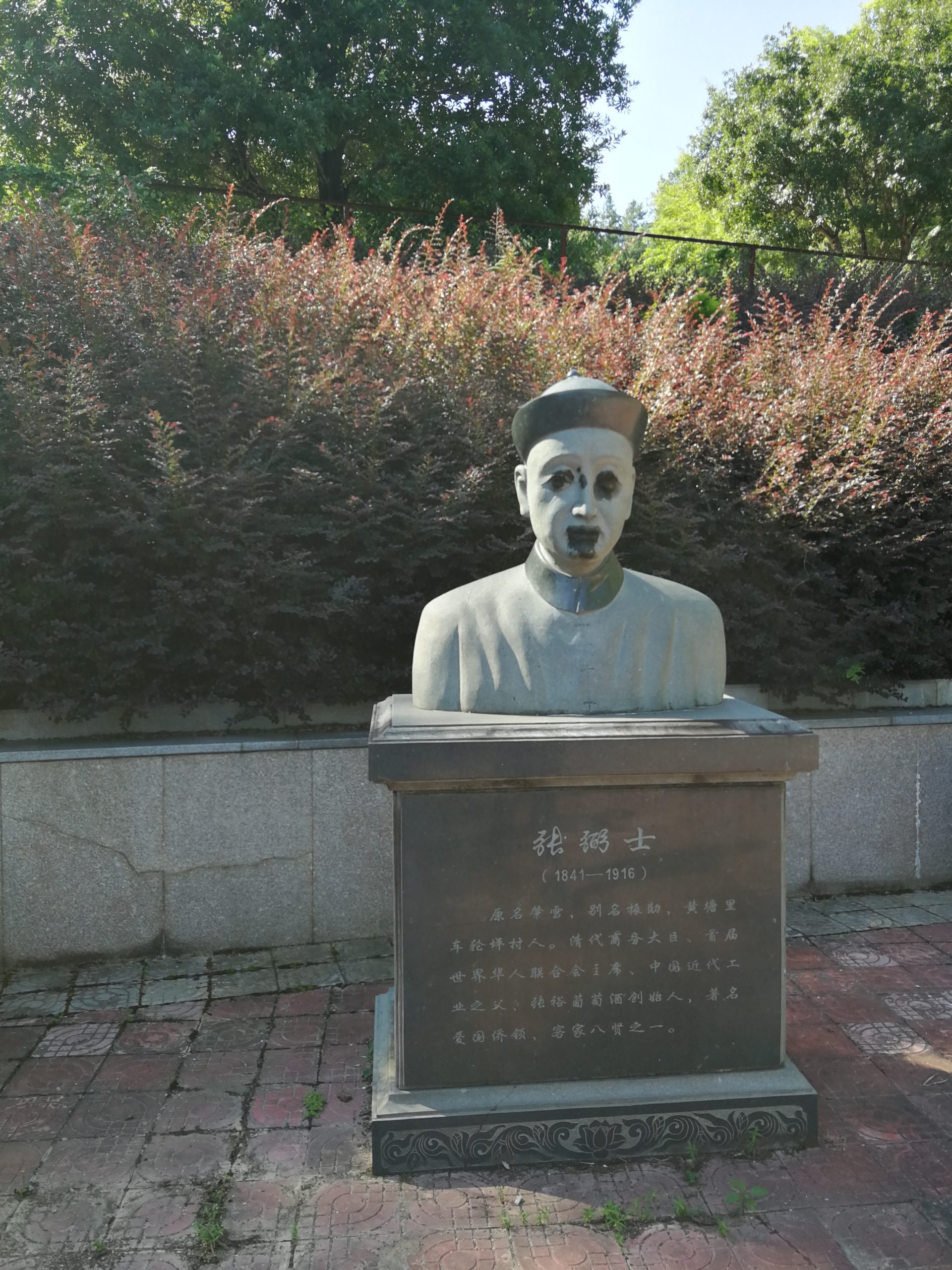

On the edge of public life and lively centres of childhood experience, wastelands thus emerge, the “marches” of common life – to use an old term that conveys the idea of these unfamiliar, largely uninhabited peripheral areas that are both disturbing and intriguing at the same time and limit the landscape of childhood. Abandoned buildings themselves are just one aspect of these spaces that are relatively difficult to define and as such, to circumscribe. However, there are signs, landmarks, “connectors or disconnectors of zones” that mark the “thresholds,” passages, and changes of milieu (Deleuze 1993: 82). Although the extract above mentions a small playing ground for children that is little invested because of its location, the children also take me twice to another, bigger park, which is isolated by the road and by its location on the other side of the river that borders the town, and where we cross paths with no one. My attention as a childhood ethnographer is immediately attracted by a derelict basketball pitch with rusted baskets – a vestige, observable in other areas, of a more active youth policy when the youth in question remained in the area. As for the children, they pay it no attention whatsoever; instead, it is the bust of a statue, in this constantly empty park, that interests them: a face carved into the stone but partly worn away, giving it a disturbing look that solicits their comments – “hao kongbu!” (好恐怖!, too scary!) (Figure 3). The semi-abandoned park and its basketball pitch are therefore part of a geography of vaguely worrying places for the children that I note in the course of our wanderings: during a stroll in a neighbouring village to the town, the eight-year-old child leading me indicates the limits of his field of exploration at a place where reputedly dangerous dogs are usually barking, even though we do not meet any on that particular day. One evening, I am walking back from the village towards the town with an eleven-year-old boy – he is there partly to accompany me and partly to run an errand, taking advantage of my presence to go out at night. However, he is keen to avoid the new, recently built road between the town and the same village, which is already in use but not yet equipped with lighting. “There may be snakes at night,” he explains. Rural areas today, experiencing the effects of Chinese growth, see the building of many roads, houses, and parks, but even in these new environments, the lack of any human presence gives these places their uncanny atmosphere, underlining the essential role of demography in the constitution of different milieus. Structural geography has suggested thinking in terms of the “oecumene”: an anthropised, inhabited everyday world where social and common activities take place as opposed to the “ereme” – classically the forest or the desert, a world where humans are less obviously at home (Berque 2010). If we transpose these categories, it could be said that the buildings abandoned to a certain extent, the wasteland, the serpents, and the semi-wild dogs that are features of their neighbourhood, indicate something like the limit between the oecumene and the ereme in this childhood experience.

Figure 3. The scary statue. Credit: author.

Figure 3. The scary statue. Credit: author.

The dynamic opposition between concentration and dispersion is not designed to reproduce the administrative opposition between urban and rural areas. Whilst it is true that within the rural world of the mountains, these “marches” of public life are particularly numerous, exacerbated by the departures and abandonment of a great number of houses, this type of environment is not unknown to the children, who, like those who live in Shanghai, have migrated to the cities. In these zones “between city and country,” urban life was concentrated in zones that were still habitable, but these were surrounded by many wastelands. The photos taken one afternoon with three sixth-year girls behind the house of one of them gives a glimpse of these wastelands all around. We wandered at random taking turns to take photos on which we can see the energy liberated by this environment – the water and mud, the wild vegetation, room to play, and lastly, the freedom, that these empty spaces confer (Figures 4 and 5). Even though we were not alone – other inhabitants of the neighbourhood were passing nearby and came to talk to us – the afternoon would have been very different if we had remained in the lanes around the houses themselves where everybody mixes. However, these wastelands are also places of vague disquiet – the girls told me they were not allowed to go there alone and spoke of rumours of organ theft.

Figure 4. Playing in the wasteland. Credit: author.

Figure 4. Playing in the wasteland. Credit: author.

Figure 5. In the wasteland surrounding the last houses, there is always someone near. For this photo, the two girls have “borrowed” a baby from a passing mother. Two children are watching us in the background. Credit: author.

Figure 5. In the wasteland surrounding the last houses, there is always someone near. For this photo, the two girls have “borrowed” a baby from a passing mother. Two children are watching us in the background. Credit: author.

The situation of these borders of public life and the general disinterest towards them opens up a space for subjectification different from that shaped by human concentration, but also limits their investment by children, and these abandoned places have never been a subject of lasting interest. Some children once took me to a closed park, on the outer edge of the neighbourhood beyond which wastelands stretched far out to a zone of buildings in the process of demolition. In this hostile environment next to a highway where vehicles and dust made the air unbreathable, the park offered a more hospitable landscape: certain zones were being demolished but others were still green, a waterway ran through it, and there were little stone pavilions where one could shelter. One only had to step over the gate to enter, and I went back alone several times in the hope of finding children playing there. The park itself was never empty: men and women were coming there to practice tai-chi, for example, as is very common in China. Nevertheless, it was not a landmark or a playground for children and adolescents (I noted just once, in my notes: “two children pass by but quickly leave”), and I soon abandoned this observation post. However, there was graffiti on the walls, rare indications of an adolescent or youth culture when young people were seldom present in the area: declarations of love, jokes, and complaints. It was clearly the abandoned nature of the park that allowed these inscriptions, forbidden elsewhere, to appear.

The special bond that can be forged between abandoned spaces and playful explorations during childhood has captured the imagination of specialists in both childhood (Cloke and Jones 2005) and ruins (DeSilvey and Edensor 2013). In my fieldworks, the abandoned spaces, linked to dispersion phenomena, provide isolated places, suitable for secrets, exploration, and activities that, if not secret, are at least sensitive in areas that are more densely occupied, and therefore are more subject to control. They also provide more intense experiences, linked mainly to fear and its strange attractions. As a result, they are not unknown to the children, who willingly share impressions and stories on these matters. Abandoned, ominous places (“the scary statue,” “the places where there are organ thieves”) occupy a privileged place, next to the nursery rhymes and a pool of shared jokes, in the oral culture typical of that age. However, rather than occupying these abandoned areas where they could find a space of freedom, everything encourages them to turn towards more populous places to which everyone gravitates and to involve in activities that are socially valued by their elders, thus confining these ruins to their stories designed to frighten and to the margins of their everyday explorations.

Conclusion – Towards an alternative demo-geography of China: The trail of children

The aim of this article was to organise material collected through the ethnography of the children’s wanderings by following the dynamics that emerge from a structural analysis of the trajectories of families, between concentration and dispersion. Where the Chinese refer in an undifferentiated manner to “backward” environments (luohou 落後; which the French would label with an equally all-encompassing term, “disadvantaged” – “défavorisé”), a vision reinforced by the presence of buildings in ruins almost everywhere, plural dynamics of differentiation emerge. In each fieldwork, there are moments of centring and decentring, synonymous for the children with a plurality of milieus and experiences, between familiar territory and peripheral and sometimes disturbing marches, as well as other more urban territories, more or less distant and structured to a greater extent by a dynamic of gathering. Above all, where the specialist literature in China reports scenes of moral bankruptcy with regard to education, or of humiliation, the children’s experience reported here appears in a very different moral and affective light: concern for others and oneself, curiosity, games, activity, and all this even though this experience takes place in an environment that the adults, often including their parents and grandparents, would not wish for them – which was the starting point for the approach –, drawing away from “elective” urban territories occupied by the “selective nomads” who can. One must even go one step further and say that the interest and richness of the experiences reported here – participating in outdoor public life or the moments of hospitality, in the midst of temporary dwellings in areas of concentration, or exploration mingled with anxiety and moments of freedom in abandoned places in zones of dispersion – are based on this poor, dilapidated, or abandoned environment, and its special affordances. Such scenes, which naturally do not exclude other moments of boredom or closure, nonetheless contrast with the image commonly given of these children and this type of environment. Highlighting them does raise a question, however: do we not risk minimising the scandal represented by these children living amongst these damaged buildings next to brand-new neighbourhoods, and by the demographic and social crisis experienced by the rural world of which the abandoned buildings are a tangible sign?

This is a key issue. The frequent act of being scandalised by the living conditions of impoverished children provides a basis for, and incitation to, a political demand for justice and change. However, the activation of moral affect that accompanies this is not without harmful consequences, since it often leads to painting a picture of these populations that is one of wretchedness. In doing so, to what extent are we rendering a service to “the vast majority of left-behind children” by stating, with the worthy aim of drawing attention to their problems of education, that they are “introverted, troubled, pessimistic, asocial, more or less apathetic, poor at interpersonal communication, self-centred and blinkered, authoritarian, unthinking, have little self-control and are egocentric” (Guo 2005)? Moreover, this line of thought produces a mediocre geography and demography of childhood that reduces the environment relevant to the child to its family (when they are “left-behind”) or administrative (when they do not have the urban hukou) situation. This brings us back to the question, raised in the introduction, of the limits of the very rigid modes of determination characteristic of a certain configuration of knowledge/power. Yet, differences in citizenship and the considerable, scarcely justifiable economic inequalities should in themselves provide a sufficient motive for demanding greater social justice, even when they are not necessarily accompanied by moral distress. Only then can the opening up of a discursive space draw attention to other facets of these Chinese childhoods and to other modes of existence for a whole set of entities to which the children are linked – the ruined buildings, as well as the populations, with their variable densities and architectures of the common, the wastelands with their affects and areas of freedom, etc. Following these children far from urban centres, relying on a structural geography and qualitative demography, would open up alternative perspectives on China, rather in the manner of travellers who choose to distance themselves from the crowded streets where, at the risk of limiting their vision, almost the entire attention of visitors is concentrated.

Acknowledgements

For their suggestions on earlier versions of this text, I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of China Perspectives, Katiana Le Mentec, and especially Judith Audin, who generously encouraged me to delve into topics I would not have gone into on my own.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants number 42171229 and 42071173).

Translated by Elizabeth Guill.

Camille Salgues is a post-doctoral researcher at the department of geographical sciences, South China Normal University, No. 55 Zhongshan Avenue West, Tianhe District, 510006 Guangzhou, China (camillesalgues@hotmail.com).

Manuscript received on 5 February 2021. Accepted on 30 June 2021.

References

AUDIN, Judith. 2017. “Dans l’antre des villes chinoises : lieux abandonnés et ruines contemporaines” (Beneath the Surface of Chinese Cities: Abandoned Places and Contemporary Ruins). Métropolitiques, 19 June 2017. https://metropolitiques.eu/Dans-l-antre-des-villes-chinoises-lieux-abandonnes-and-ruines-contemporaines.html (accessed on 11 June 2021).

BERQUE, Augustin. 2010. Écoumène: introduction à l’étude des milieux humains (Oecumene: Introduction to the Study of Human Environments). Paris: Éditions Belin.

BÜHLER-NIEDERBERGER, Doris. 2010. “Childhood Sociology in Ten Countries: Current Outcomes and Future Directions.” Current Sociology 58(2): 369-84.

BREVIGLIERI, Marc. 2014. “La vie publique de l’enfant” (The Child’s Public Life). Participations 9(2): 97-123.

CHICHARRO, Gladys. 2010. Le fardeau des petits empereurs : une génération d’enfants uniques en Chine (The Burden of the Little Emperors: A Generation of Only Children in China). Nanterre: Société d’ethnologie.

CLOKE, Paul, and Owain JONES. 2005. “‘Unclaimed Territory’: Childhood and Disordered Space(s).” Social & Cultural Geography 6(3): 311‑33.

DAVIN, Delia. 1996. “Affreux, sales et méchants : les migrants dans les médias chinois” (Delinquent, Ignorant, and Stupid: Migrants in the Chinese Press). Perspectives chinoises 38: 6‑11.

DE CERTEAU, Michel. 1980. L’invention du quotidien (The Practice of Everyday Life). Paris: 10/18.

DELEUZE, Gilles. 1988. Le Pli. Leibniz et le Baroque (The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque). Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

——. 1993. “Ce que les enfants disent” (What Children Say). In Gilles DELEUZE, Critique et clinique (Essays Critical and Clinical). Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit. 81‑8.

DESILVEY, Caitlin, and Tim EDENSOR. 2013. “Reckoning with Ruins.” Progress in Human Geography 37(4): 465‑85.

DESMARAIS, Gaëtan. 2001. “Pour une géographie humaine structurale” (Elements of Structural Geography). Annales de Géographie 110(617): 3‑21.

DESMARAIS, Gaëtan, and Gilles RITCHOT. 2000. La géographie structurale (Structural Geography). Paris: L’Harmattan.

DUAN, Chengrong 段成榮, LÜ Lidan 呂利丹, GUO Jing 郭靜, and WANG Zongping 王宗萍. 2013. “我國農村留守兒童生存和發展基本狀況” (Woguo nongcun liushou ertong shengcun he fazhan jiben zhuangkuang, Basic Conditions of Life and Development of the Chinese Rural Left-behind Children). Renkou xuekan (人口學刊) 35(199): 37-49.

FLORENCE, Éric. 2006. “Les débats autour des représentations des migrants ruraux” (The Debates Surrounding Representations of Rural Migrants). Perspectives chinoises 94: 13-26.

FROISSART, Chloé. 2003. “Les aléas du droit à l’éducation en Chine” (The Vagaries of the Right to Education in China). Perspectives chinoises 77: 48-56.

GIBSON, James Jerome. 2014. Approche écologique de la perception visuelle (An Ecological Approach to Visual Perception). Bellevaux: Éditions Dehors.

GLEVAREC, Hervé. 2009. La culture de la chambre : préadolescence et culture contemporaine dans l’espace familial (Bedroom Culture: Pre-adolescence and Contemporary Culture within the Family Space). Paris: la Documentation française.

GUO, Sanling 郭三玲. 2005. “農村留守兒童教育存在的問題, 成因及對策分析” (Nongcun liushou ertong jiaoyu cunzai de wenti, chengyin ji duice fenxi, Analysis of the Causes and Solutions to the Existing Problems in the Education of Rural Left-behind Children). Hubei jiaoyu xueyuan xuekan (湖北教育學院學刊) 22(6): 86-8.

HARVEY, David. 2008. “The Right to the City.” New Left Review 53: 23-40.

HOLLOWAY, Sarah L., and Gill VALENTINE (eds.). 2000. Children’s Geographies: Playing, Living, Learning. London: Routledge.

JAMES, Allison. 2009. “Agency.” In Jens QVORTRUP, William A. CORSARO, and Michael-Sebastian HONIG, The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 34-45.

LANCY, David. 2012. “Unmasking Children’s Agency.” AnthropoChildren, October 2012. https://popups.uliege.be/2034-8517/index.php?id=1253 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

LAUGIER, Sandra. 2008. “Règles, formes de vie et relativisme chez Wittgenstein” (Rules, Forms of Life, and Relativism in Wittgenstein). Noesis 14: 41-80.

LING, Minhua. 2019. The Inconvenient Generation: Migrant Youth Coming of Age on Shanghai’s Edge. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

MAH, Alice. 2012. Industrial Ruination, Community, and Place: Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

RICHAUD, Lisa, and Ash AMIN. 2020. “Life amidst Rubble: Migrant Mental Health and the Management of Subjectivity in Urban China.” Public Culture 32(1): 77‑106.

SALGUES, Camille. 2012a. “‘Ici c’est comme le Sichuan après le tremblement de terre.’ Paysage moral des enfants de migrants ruraux à Shanghai” (“Here it is like Sichuan after the Earthquake”: Mental Landscape of the Children of Rural Migrants in Shanghai). In Didier FASSIN, and Jean-Sébastien EIDELIMAN, Économies morales contemporaines (Contemporary Moral Economies). Paris: La Découverte. 73-93.

——. 2012b. “Ethnographie du fait scolaire chez les migrants ruraux à Shanghai. L’enfance, une dimension sociale irréductible” (An Ethnography of Schooling among Rural Migrants in Shanghai. Chilhood, an Unsolvable Social Dimension). Politix 99(3): 129-52.

SHEN, Zhifei 沈之菲. 2007. “更多的接納, 更多的融合: 外來民工子女在上海城市的融合問題研究” (Gengduo de jiena, gengduo de ronghe: wailai mingong zinü zai Shanghai chengshi de ronghe wenti yanjiu, More Acceptance, More Integration: Research on the Issue of the Integration of Migrant Workers’ Children in Shanghai). Shanghai jiaoyu keyan (上海教育科研) 2007(11): 25-8.

STAVO-DEBAUGE, Joan. 2017. Qu’est-ce que l’hospitalité ? Recevoir l’étranger à la communauté (What is Hospitality? Welcoming the Stranger into the Community). Montréal: Éditions Liber.

THÉVENOT, Laurent. 1997. “Un gouvernement par les normes. Pratiques et politiques des formats d’information” (The Power of Standards. Politics and Pragmatics of Information Standards). In Bernard CONEIN, and Laurent THÉVENOT, Cognition et information en société (Cognition and Information in Society). Paris: Éditions de l’EHESS. 205‑41.

WU, Ka-ming, and Jieying ZHANG. 2019. “Living with Waste: Becoming ‘Free’ As Waste Pickers in Chinese Cities.” China Perspectives 117: 67-74.

ZHOU, Mingchao. 2016. “Habiter la ville. Les stratégies identitaires des élèves scolarisés en zone urbaine face au stigmate d’‘enfants de nongmingong’” (Living in the City: The Identity Strategies of Schoolchildren in an Urban Setting Confronted by the Stigma of Being “Children of Nongmingong”). Perspectives chinoises 137: 75-83.

[1] I give more details of this passage elsewhere, where I analyse it from another perspective (Salgues 2012a).

[2] The agreement should not necessarily be thought of as a contract or a negotiation, which are just one very specific way in which human beings reach agreements amongst themselves, albeit a very important one in modern societies (Laugier 2008). Neither should it be thought of as necessarily horizontal. In the scene described here at school, the agreement on the forms that the dirty and the clean take mainly depends on the decision of the adults, the teachers. Speaking of an “agreement” does not assert a horizontality between players negotiating with each other but leads to reflect on ways to live in common that cannot be reduced to “a single model of social norms that cement groups of people” (Thévenot 1997).