BOOK REVIEWS

Good Girls and the Good Earth: Shi Lu’s Peasant Women and Socialist Allegory in the Early PRC

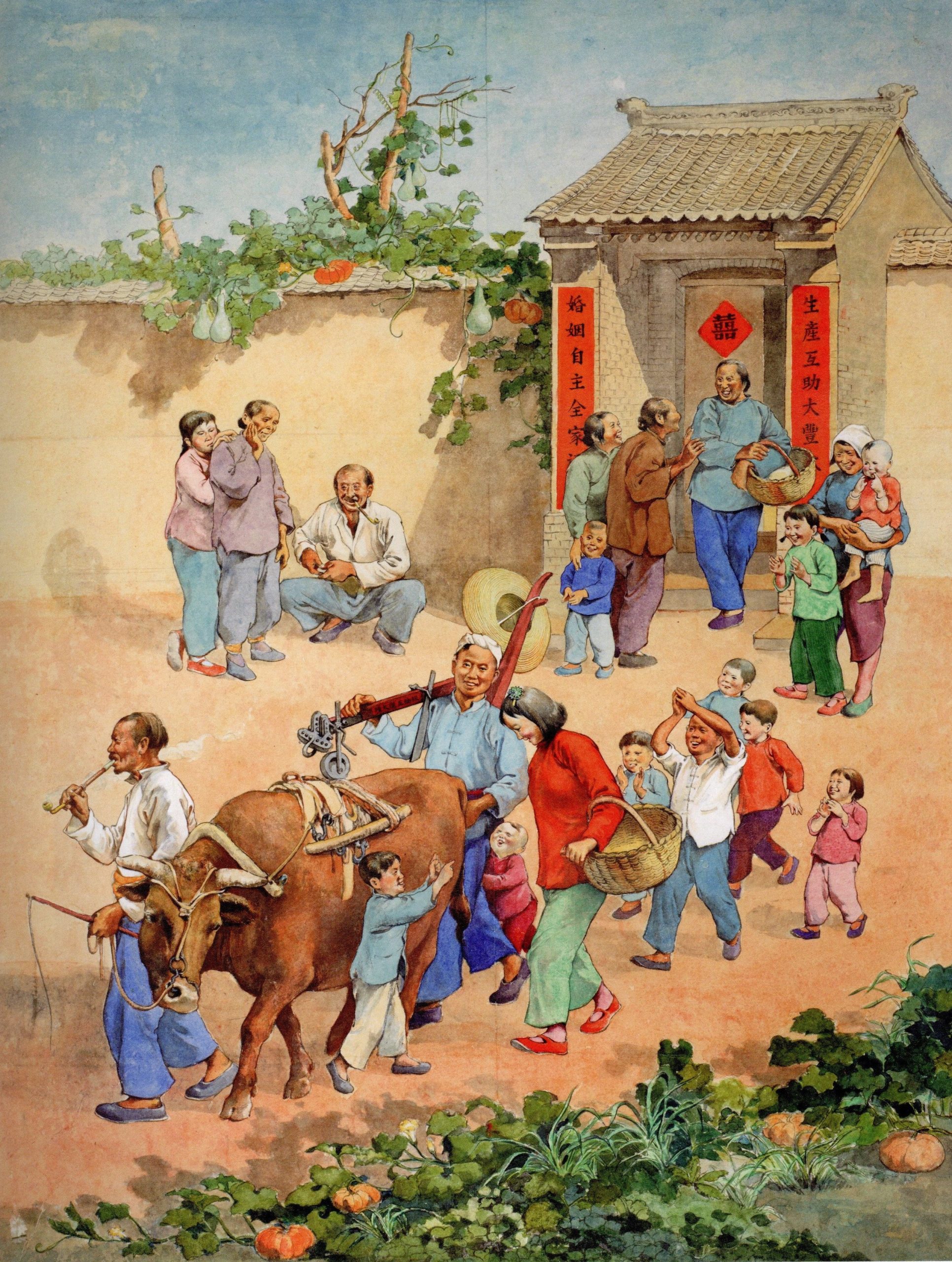

The 1952 painting Happy Marriage (Xingfu hunyin 幸福婚姻, Figure 1)[1] depicts a scene of unambiguous jubilance. Walking behind their healthy ox through a throng of clamouring children, a newlywed couple reveals their joy – and a bit of embarrassment – through their wide smiles. As they embark on a new life together, their relaxed body language suggests that they are bound not by tradition but by free choice, a distinction that would lead to a happy union and prosperous future. Thematically consistent with a fertile vegetable patch in the foreground, an auspicious couplet flanking the gate of the couple’s courtyard declares: “Working together makes a bumper harvest, marrying the partner of one’s choice leads to a happy family” (Shengchan huzhu da fengshou, hunyin zizhu quanjiafu 生產互助大豐收, 婚姻自主全家福). Reinforced by the couplet, this painting yokes traditional auspicious sentiment and Maoist messaging. The image was created by the Xi’an-based official artist Shi Lu 石魯 (1919-1982) in the style of a New Year’s picture (nianhua 年畫), a genre of folk art that gained modern footing when it was professionalised and popularised by political establishments of twentieth-century China.[2]

Figure 1. Shi Lu 石魯, Happy Marriage (Xingfu huyin 幸福婚姻). 1952. New Year’s picture (nianhua). 83 x 62 cm. Credit: the Shaanxi Artists Association.

Figure 1. Shi Lu 石魯, Happy Marriage (Xingfu huyin 幸福婚姻). 1952. New Year’s picture (nianhua). 83 x 62 cm. Credit: the Shaanxi Artists Association.

Works of art throughout the Maoist period that feature marriage as the subject connected national policy and art, highlighting the propagandistic potential of visual images. Published as a poster, Happy Marriage was one such work created to support the 1950 Marriage Law, a hallmark legislation that regulated matters related to marriage, sex, and gender relations in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).[3] While efforts to grant women greater equality had been made since the May Fourth movement (1919) and were supported by the Nationalists and Communists alike before 1949, the prioritisation of the Marriage Law for the PRC signified the urgency with which the Communists inserted state intervention into structures previously exclusive to the private sphere. By ostensibly governing marriage, the state effectively prioritised women’s function in procreation and social stabilisation over other roles (Evans 1995). The law further reinforced a political trope initially established in the May Fourth period, that women were victims in a socially repressive feudal China and had to be rescued by a new political system (Ko 1994: 2-5; Bailey 2012: 58-67). Indeed, the Marriage Law was regarded as an arm of the Party’s ongoing land reform as the organisation of family was intricately connected to China’s labour potential (Hershatter 2019: 221-6). While Shi Lu’s nianhua promoted marriage by choice as protected by the law, it also foregrounded the connection of marriage to economic productivity in the countryside.[4]

An image like Happy Marriage is best understood in the context of corresponding policy, but it also functions as a document of the evolving and at times conflicting course taken by official artists as they sought to reconcile the needs of the state with their personal volition. As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) selectively adopted a set of globally oriented political theories and praxis, the shifted emphasis from landscape to figural painting constituted a global turn for art of Maoist China, a process that had begun in the Late Imperial period and continued through the Republican period. With examples ranging from self-portraits to commercially produced calendar girls, the corporeal human body was injected with realism and readied for social engagement.[5] As images of women appeared in Chinese art with greater frequency and realism in the twentieth century, the visual precedent for this shift was found as much in the Western foundation on which the modern Chinese art curriculum was built as in premodern Chinese art.[6]

By 1949, images of figures, particularly women, were firmly established as sites of broader social significance as the communist state relied on art to influence the populace, especially when images could provide legibility to obtuse policies. The evolution of women’s roles during this period of state-sponsored “women’s liberation” can be traced through these widely circulated and well-studied visual examples, exemplified by, but not limited to, images of androgynous “iron women” and eroticised female heroes. Scholarship on such images and themes in propaganda art and model operas (Chen 1999; Evans 1999; Ip 2003; Di 2010; Pang 2014) has established a growing discourse on the gender dimensions of socialist culture. To a lesser extent, images of women in the post-Maoist era have also been examined for their restoration of traditional femininity (Evans 1993, 2000; Li 2019). These overlapping bodies of scholarship show that images of young women have been continuously enlisted as visual embodiments of China’s political transitions, existing as national symbols of modernisation rather than as agents of their own accord. How did artists respond to political directives through the employment of specific images, styles, and conventions? What does the ubiquity of female figures, particularly those bearing rural attributes, inform us about the position of this social group in the early PRC? Moreover, what does the Sinicisation of the universal portrayal of female beauty signify about the orientation of Chinese art within a global socialist framework?

To investigate these questions, this article focuses on the portrayal of rural women by Shi Lu, an artist-cadre noted for his artistic and administrative contributions to the formation of a northwestern regional apparatus within the centralised art system. It specifically examines how the development of a chaste, allegorical version of female beauty shed the sexuality of earlier images of women in Chinese visual history and satisfied the political needs of the communist state in the early Maoist period. Seen acutely in Shi Lu’s oeuvre, political expectations and global art traditions gave rise to the portrayal of young peasant women in Maoist China. I argue that transparently propagandistic images such as Happy Marriage, along with Shi’s more ambiguously rendered images of peasant girls, promoted economic development that hinged on the balance between China’s rural and urban populations. While meeting their revolutionary potential as members of the exalted peasantry, rural women also fulfilled their inescapable role in the long, universal history of art as objects of gaze, desire, and fantasy. The convergence of global influences and indigenous traditions gave form to the nebulous task assumed by cultural workers to support state policies.

Shi Lu’s peasant girls and Mao’s industrialisation efforts

This article focuses on works that were exhibited and circulated in selective venues such as exhibitions and art magazines but were not commonly reproduced as propaganda posters. As such, they have generally evaded the level of political scrutiny received by more visible images. Given the limited role of women as subjects in traditional Chinese art, specifically ink painting, the conspicuous appearance of contemporary young women – mostly peasants – in Maoist-era ink painting invites inspection regarding its purpose.[7]

Even though images of young peasant women in the PRC were common, those featuring women from ethnic minorities emerged as a distinct and highly visible sub-genre.[8] Celebrated as ethnographic studies of minority culture, these images supported the socialist state’s promotion of national cohesion while also engaging with the global trend of primitivism, in which European artists exoticised women from cultures outside of their own. For example, Li Huanmin 李喚民 (1930-) and Zhou Changgu 周昌谷 (1929-1986) are known for their images of Tibetan girls, while Huang Zhou 黃冑 (1925-1997) gained acclaim for his depictions of Uyghur women. Although these examples show the broad appeal of young women as artistic subject matter, they do not fully contextualise Shi Lu’s portrayal of primarily Han women.

An artist famous for his fiery charisma and theoretical formulations, Shi Lu’s portrayals of young peasant women offer us a close view of how an official artist’s political transformation from the son of a prominent Sichuan family to a Yan’an revolutionary provided the credentials for his rise within the art establishment. In 1949, he became the first vice chairman and de facto spokesperson of the Xi’an Branch of the Chinese Artists Association (Zhongguo meishujia xiehui Xi’an fenhui 中國美術家協會西安分會, CAA Xi’an), a professional association under the Communist Party’s propaganda department.[9] While maintaining his dual role as a member of the creative intelligentsia and state functionary, Shi Lu negotiated the juncture of historical and political narratives that defined the first decade and a half of the PRC.

Existing Western scholarship has focused on Shi Lu’s landscapes and persecution during the Cultural Revolution. Chinese publications, by contrast, typically portray him as an individualist who transformed ink painting for Maoist China.[10] The artist established himself on the national stage through the monumental ink painting Fighting in Northern Shaanxi (Zhuanzhan Shaanbei 轉戰陝北, 1959), a state commission created to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the PRC (Andrews 1995; Noth 2009; Hawks 2017). Although he is associated with this iconic portrayal of Mao that integrates the genres of portraiture and landscape, an examination of his complete body of work shows more interest in anonymous women, children, and the elderly – social categories that have only been infrequently and inconsistently depicted in Chinese art.[11] These previously marginalised groups gained visibility as their active enlistment into the socialist state acquired political significance.

In Shi Lu’s work from the 1950s, young women are sometimes the primary focus or are integrated into the larger landscape. Country Girl (Cun gu tu 村姑圖, Figure 2) portrays a seated peasant girl whose unassuming appearance enhances her natural beauty. She wears a simple red jacket with a green scarf, remaining unadorned except for a plain hairbow.[12] This delicate portrait study highlights the subject’s peasant identity: her ruddy cheeks and pink lips show not vanity but her youth and exposure to the elements of her rural environment. This undated work matches the artist’s realistic style in the early 1950s before he narrowed his specialisation to ink painting (guohua 國畫), although he kept working on a variety of mediums and genres, including nianhua, woodcuts (muke 木刻), and oil painting (youhua 油畫), all utilising more adherence to form-likeness than the inherent abstraction of ink painting.

Figure 2. Shi Lu 石魯, Country Girl (Cun gu tu 村姑圖). Undated. Ink and colour on paper. 49 x 37cm. Credit: Robert Ellsworth.

Figure 2. Shi Lu 石魯, Country Girl (Cun gu tu 村姑圖). Undated. Ink and colour on paper. 49 x 37cm. Credit: Robert Ellsworth.

This modest portrait is a transitional work in both style and subject matter. Even though the identity of the figure is unknown, she seems to be a specific individual based on the artist’s observation, not a generic type in the lineage of “beautiful women” (meiren 美人) painting. She can be considered a counterpoint to portraits of political figures in ink medium but she is not aggrandised in a way that makes the work comparable to them. The girl is seated in three-quarter profile, unaware of the viewer’s gaze, and thus follows the convention of Western portrait painting. Shi Lu would have found it appropriate within the artistic climate of the time to create this type of well-observed and literal depiction of peasants in the early 1950s.

Although outnumbered by images of elite women, female agricultural labourers appeared in Chinese art long before their politicised identification as “female peasants” in the Maoist period. The visual and semantic process of distinguishing peasants (nongmin 農民) from urban residents (jumin 居民) correlated with seismic social changes as urbanisation carved out cities as distinct zones of commerce – and thus inaugurated a process by which cities gained advantage over the countryside by the first half of the twentieth century (Lu 1999: 5-8). The process of urbanisation, while propelling forward selective regions of China in economic development, also drove a social wedge between urban and rural residents (Brown 2008: 19). From the beginning of this process of differentiation, one’s status as either a peasant or an urban resident carried significant socioeconomic impact. Even though peasants were championed as the new political elite, their quality of life did not correspond with their political status (Cohen 1993: 157). Thus, even as urban residents extolled the virtues of peasants, few desired to be one.

As Maoist China centred the social construct of the Chinese peasantry in its political formulations, the portrayal of peasants became a means of visualising socialist modernity. We see in paintings featuring peasants a new relationship between not only the artist and the viewer but also the subject, forming a triangulated dynamic that required the artist to complete the nebulous task of capturing the symbolic essence of peasants through direct observation. Artists participated in the delineation of urban and rural spheres through their work, maintaining the paradox that peasants were both celebrated and disadvantaged. Even though the period examined in this article overlapped with the Great Leap Forward and the Great Famine, the contemporaneous artworks did not reflect the dire conditions in the countryside. Instead, they captured untroubled facets of rural life and labour, as well as optimistic depictions of industrial progress in rural China.

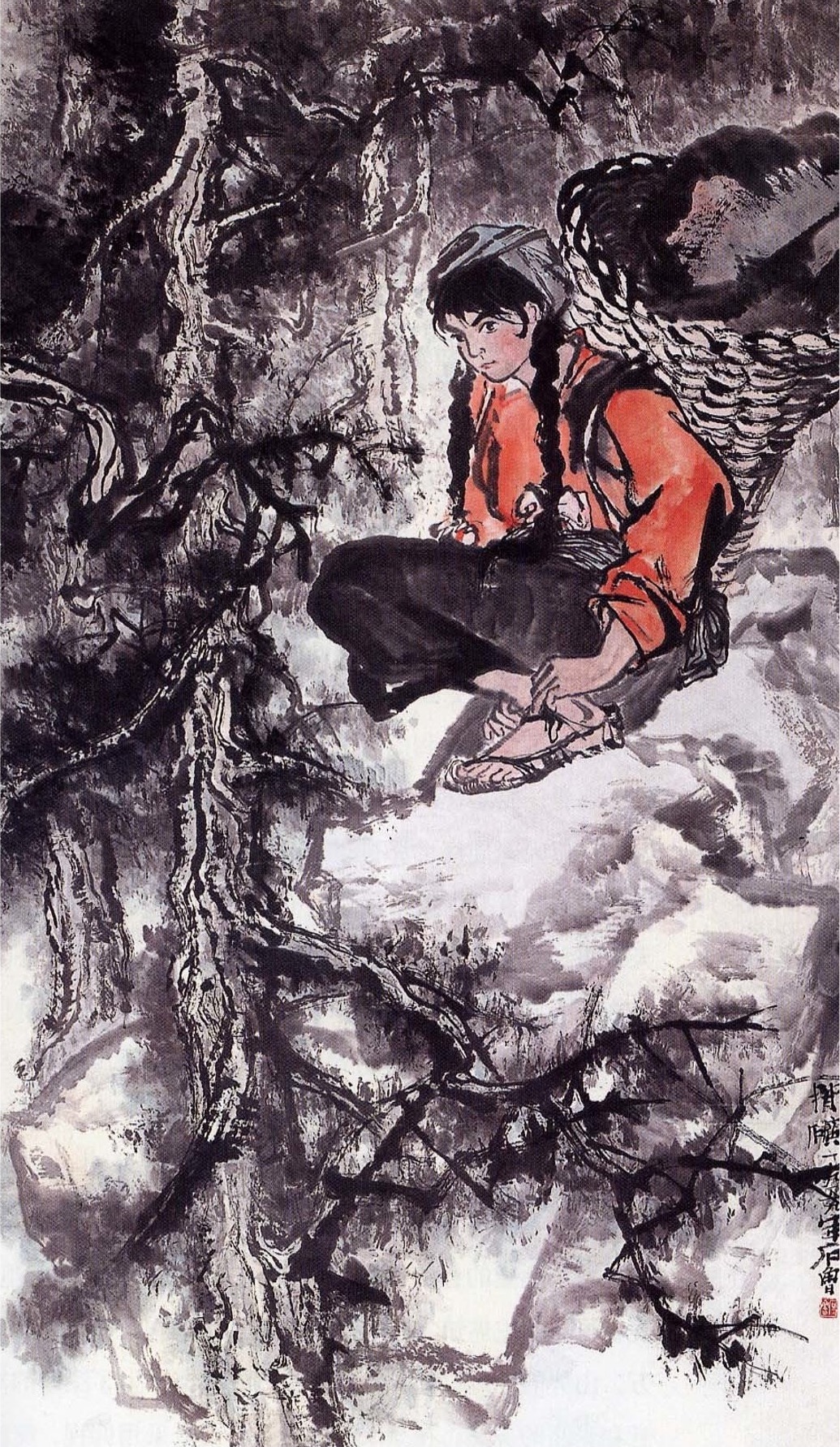

Shi Lu’s straightforward Country Girl, likely a practice study, seems to have paved the way for more experimental portrayals of peasant girls that are less realistic, more abstract, and generalised. In the 1959 work Carrying Coal (Bei kuang 背礦, Figure 3), Shi Lu portrays a young woman of similar status and appearance as Country Girl. In this painting, a young woman hauls a heaping basket of raw coal on her back. Her peasant status is conveyed through her baggy clothes and head wrap, in addition to the type of work she performs. Despite the young woman’s modest wardrobe, the artist has taken clear measures to portray her beauty, characterised by her flushed cheeks, rosy lips, large black eyes, and thick braids tied together with flouncy bows. The depiction of a strong female body and expressive bulging eyes – a convention possibly adopted from Chinese opera – points to a new configuration of figure painting that sidestepped visual conventions to inscribe more expressive meaning on the body.

Figure 3. Shi Lu 石魯, Carrying Coal (Bei kuang 背礦) (version 2). 1959. Ink and colour on paper. 171 x 94 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Figure 3. Shi Lu 石魯, Carrying Coal (Bei kuang 背礦) (version 2). 1959. Ink and colour on paper. 171 x 94 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Moreover, the level of realism seen in Country Girl is rare for a figural depiction in traditional ink painting; even though the figure’s generic features do not suggest a portrait, the artist likely based the painting on observational sketches. In contrast to its generic precedents in Chinese painting, the fully realised female body borrowed from Western conventions; however, despite its relative realism, the coal-carrying girl remains an image of idealised beauty that rearticulates the genre of meiren painting. A comparison of the two paintings reveals a clear stylistic shift from the early to the late 1950s as the trope of the young peasant woman gained standardisation in embodying a recognisable ideal.

The strangeness of the coal-carrying figure is further emphasised by the setting, a shallow space framed by aggressively rendered trees and rocks that enclose the figure in a threatening manner. The figure’s fixed gaze is at once determined and anxious; yet she is clearly embedded in this environment. The placement of an anonymous peasant girl in a gesturally painted ink landscape with pines trees, a symbolic motif typically reserved for the literati, shows Shi Lu’s deliberate break from convention to create a painting that is a bricolage of ink traditions, Western realism, and socialist subject matter.

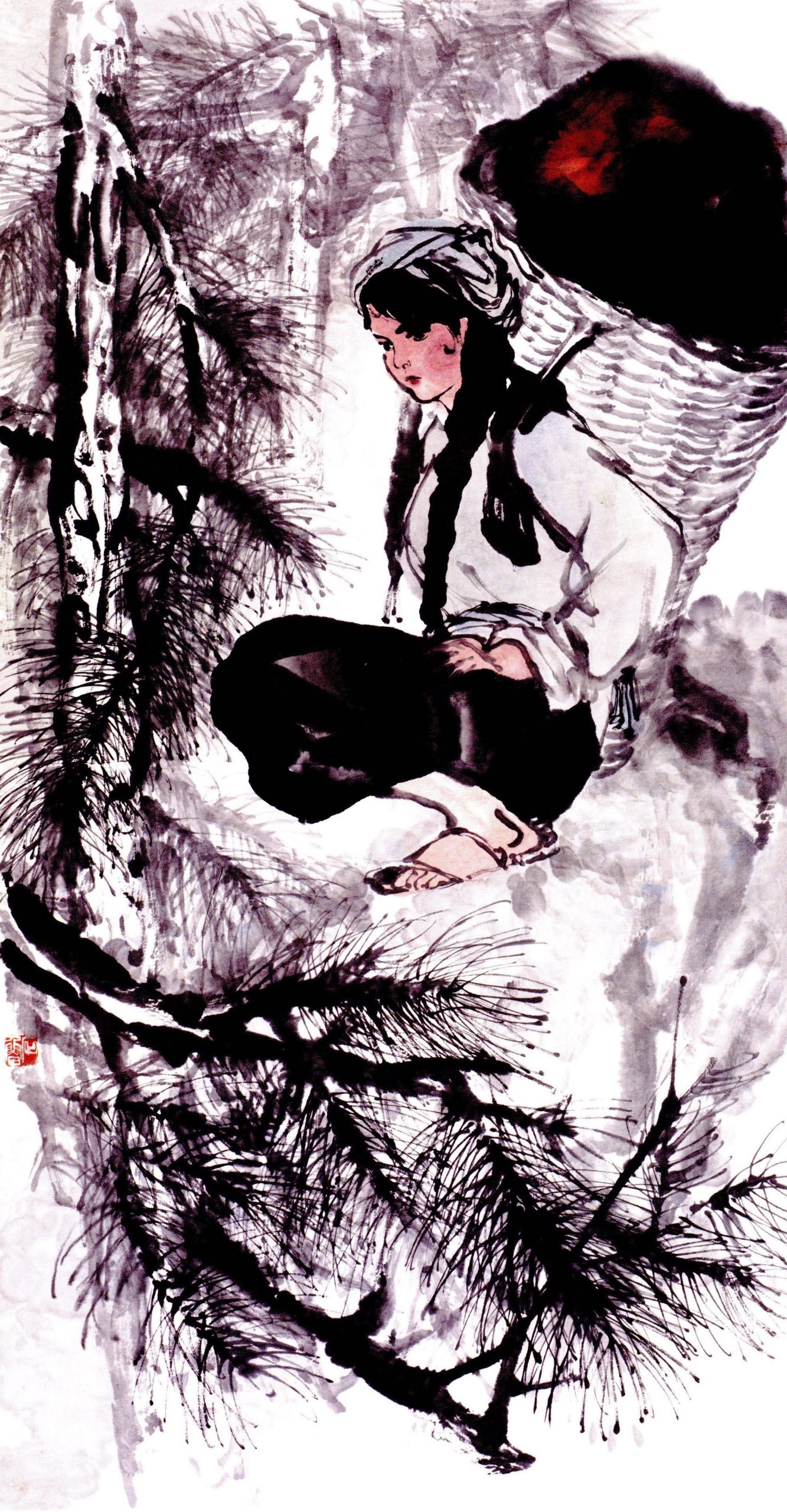

Figure 4. Shi Lu 石魯, Carrying Coal (Bei kuang 背礦) (version 1). 1958. Ink and colour on paper. 139 x 74 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Figure 4. Shi Lu 石魯, Carrying Coal (Bei kuang 背礦) (version 1). 1958. Ink and colour on paper. 139 x 74 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

An earlier version of Carrying Coal from 1958 (Figure 4) suggests the importance of this composition for Shi Lu, who replicated nearly all elements of the earlier work in the 1959 painting, except for extending the girl’s hands down to her feet to tie her sandal. With this small modification, the girl immediately acquires a purpose for her respite and offers the artwork a sense of narrative temporality. The artist also adopted a starker palette: changing the girl’s jacket from white to red and opting for darker ink instead of the softer, more washed tones in the earlier painting in the background, thereby creating a more ominous atmosphere. Differences between the versions reveal a surprising degree of modification taken with paintings supposedly based on real-life observation. The artist’s choice to repeat the coal-carrying girl points to her thematic significance as a subtle nod to the Mao’s industrialisation efforts. As an artist based in Shaanxi, a province whose mountainous regions participated in the coal mining efforts of the Great Leap Forward, Shi Lu seems to have created an image that supported the national industrial agenda.[13] The theme of coal mining was reiterated in visual form through mass-produced propaganda posters: Coal Feeds Industry (Mei shi gongye de shiliang 煤是工業的食糧, 1952) is an illustrated diagram on the various applications of coal – household energy, power generation, fuel – and boasts the target: “Our country will have 115 large-scale mines in five years.” Although visually dissimilar, the propaganda poster and Carrying Coal belong to the same visual programme for promoting coal mining; whereas the poster functioned didactically, Shi Lu’s painting inspired viewers through indirect evocation – a process that normalised women’s participation in industrial labour and restored their status as subjects of idealised beauty consistent with visual traditions in China and in other parts of the world.

Shi Lu’s observations on foreign women, labour, and figural art

The significance of the young peasant woman for Shi Lu finds little explicit explanation from the artist. A brief but important period of the artist’s career, however, offers insight. Although Shi Lu’s exposure to non-Chinese art was limited, his political convictions as a communist cadre forged in him a cosmopolitan worldview that saw China as a critical player in world history and current events, a process coined “socialist cosmopolitanism” by Nicolai Volland (2017). At the national level, the artist participated directly in the state’s efforts to establish China as a leader of the so-called “Third World” in the eventual formation of the Non-aligned Movement (Brazinsky 2017). Cultural workers such as Shi Lu were dispatched abroad as cultural attachés to liaise with China’s political allies. Before establishing himself thanks to Fighting in Northern Shaanxi, the rising young artist participated in two such trips, to Egypt and India, that solidified his commitment to the ink medium and continued exploration of figuration (Wang 2019).

The artist’s visits allocated time for travel and sketching in the host countries. Among the published images from these trips are paintings of Indian women dancing, venerating, and working, and no fewer than three paintings of Egyptian women carrying loads on their heads (Figure 5). In them, the female subjects are strong and statuesque, valorised for carrying children, jars, and crops on their heads. The distilled isolation of the artist’s experience abroad offers a consolidated view into his choice of the female subject, albeit mediated through an exoticising lens. The appeal of rural women engaged in labour crossed national boundaries for Shi Lu as he produced not only paintings of women in India and Egypt, but also wrote about his impressions in the essay “Indomitable Women – Impressions from Sketching in India” (Ding tian li di de nürenmen – Yindu xiesheng suigan zhi yi 頂天立地的女人們 – 印度寫生隨感之一) (Shi 2003a). The text offers a rare glimpse into the artist’s feelings about women’s social role, though expressed through the lens of a foreign culture. Shi Lu speaks at length about the tradition of head-carrying:

There are many women like them in the world; from birth their heads are adorned not with flowers but serve as roofs of houses. These women carry an immense burden on their heads every day! (Ibid.: 35)

Figure 5. Shi Lu 石魯, Village Maiden (Nongcun shaonü 農村少女). 1956. Ink and colour on paper. 50 x 37 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Figure 5. Shi Lu 石魯, Village Maiden (Nongcun shaonü 農村少女). 1956. Ink and colour on paper. 50 x 37 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

The essay reveals the artist’s simultaneous respect and sympathy for women whose lives were dominated by a specific form of manual labour. Presented as ethnographic observation, the essay extols the virtues of Indian women while exoticising their training in head-carrying. Shi Lu’s seemingly benign observations about a foreign culture coupled with his repeated motif of female labour aligned with Maoist formulations at the time. As anthologised in Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, the historical condition of women’s exploitation is intimately coupled with Mao’s call for advancing women’s sociopolitical standing to incentivise their participation in the labour force (Mao 1966: 294-8). Although it cannot be determined if the artist’s observations of India correlated with his feelings about the status of Chinese women, his sentiments reflect the Maoist rhetoric of the time. Without directly referencing China, Shi Lu’s visual and textual formulations from his trips abroad show how images of young women and labour became entwined subjects for the artist by the mid-1950s. By the late 1950s, the artist continued to paint young peasant women even as he bolstered his reputation through national-level commissions.

Figure 6. Shi Lu 石魯, Clever Girl Embroidering the Landscape (Qiao nü xiu hua shan 巧女繡花山). 1959. New Year’s picture (nianhua). 75 x 43 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Figure 6. Shi Lu 石魯, Clever Girl Embroidering the Landscape (Qiao nü xiu hua shan 巧女繡花山). 1959. New Year’s picture (nianhua). 75 x 43 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

In the same year as Fighting in Northern Shaanxi, Shi Lu continued to create images of peasant women. A nianhua from 1959, Clever Girl Embroidering the Landscape (Qiao nü xiu hua shan 巧女繡花山, Figure 6), portrays a girl strikingly similar to the coal-carrying girl. She also wears long braids with bows and a red jacket that envelopes her C-shaped body. Instead of performing agricultural or industrial labour, she is embroidering a depiction of the idyllic landscape outside her window. Her features are more delicate and feminine – the result of the fine-line style employed for this painting – but the undeniable similarities between her and the coal-carrying girl suggest another facet of women’s political and economic identity: their responsibility for domestic labour, a sphere exclusive to women. Mirror images of each other, the two portrayals offer a restoration of women’s traditional role in the domestic sphere to balance her new role as an industrial labourer outside the home.

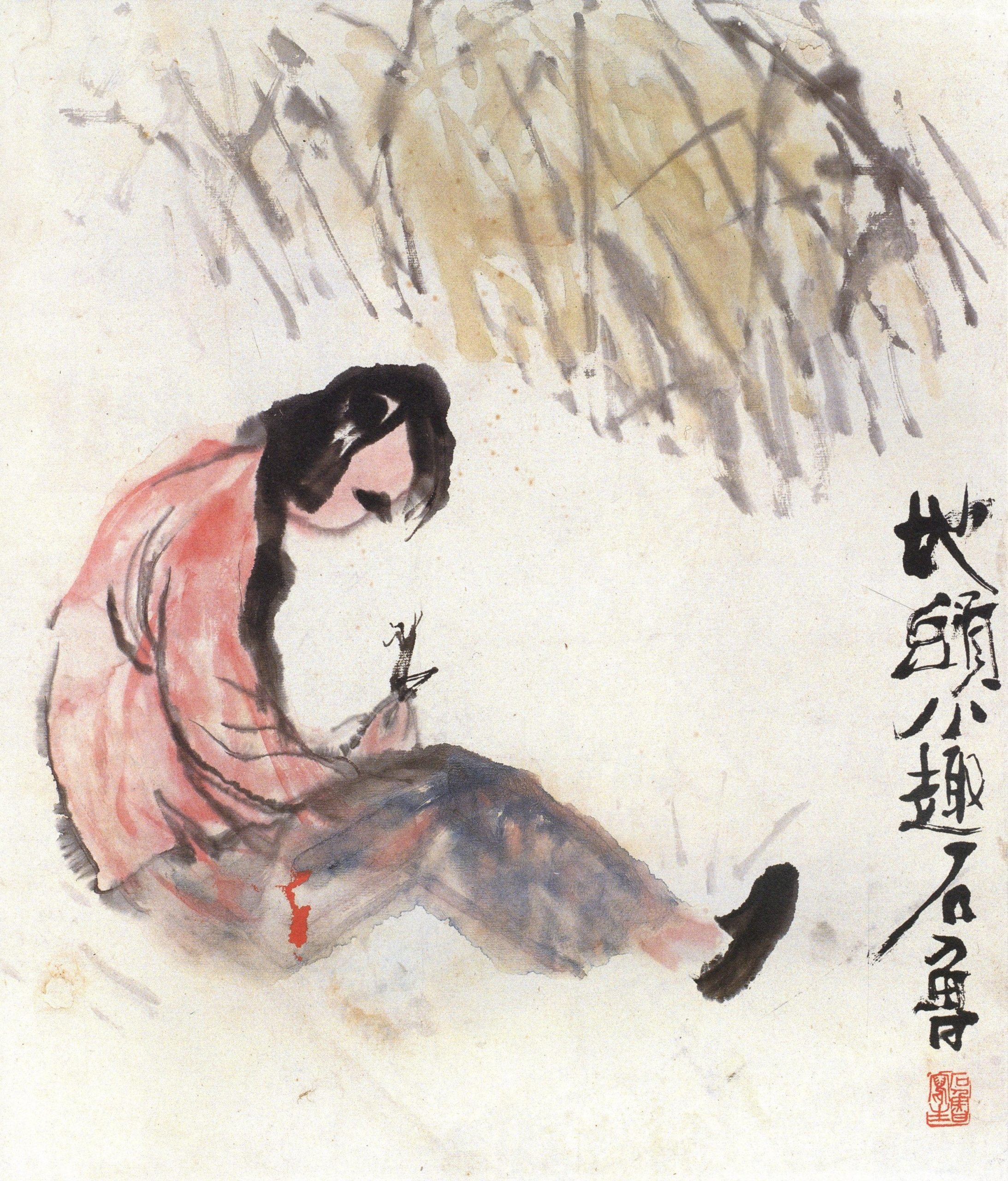

Shi Lu’s later images of young women come into greater thematic clarity and stylistic distinction while evolving toward formal abstraction. The complexity of Carrying Coal gives way to more abstract but accessible images that associate young peasant women with nature. In the 1963 Looking at the Grasshopper (Ditou xiao qu 地頭小趣, Figure 7), a village girl gazes attentively at a grasshopper in her hands. Like many other images, she sits on the ground, her body forming a curve in profile, framed by what appears to be wheat stalks in the background. In the painting Two Girls (Liangge guniang 兩個姑娘, Figure 8) from the same year, two young women braid each other’s hair. Besides the crouching figures and a straw hat, the only other compositional element is a bird. In both paintings, Shi Lu emphasises the unadorned earthiness of the peasant girls through their direct connection to the natural world.

Figure 7. Shi Lu 石魯, Looking at the Grasshopper (Ditou xiao qu 地頭小趣). 1963. Ink and colour on paper. 51 x 43 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Figure 7. Shi Lu 石魯, Looking at the Grasshopper (Ditou xiao qu 地頭小趣). 1963. Ink and colour on paper. 51 x 43 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Figure 8. Shi Lu 石魯, Two Girls (Liangge guniang 兩個姑娘). 1963. Ink on paper. 64 x 68 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Figure 8. Shi Lu 石魯, Two Girls (Liangge guniang 兩個姑娘). 1963. Ink on paper. 64 x 68 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

The establishment of young peasant girls as a common socialist visual type enabled viewers to recognise the female form as a gestalt in works such as Looking at Grasshopper and On the Way to Work (Shang gong 上工, Figure 9). Despite their abstract style rendered in dabs of wet ink monochrome, the forms in the lower section of the latter painting are legible as young women. Even without a clear view of the subject’s face or body, the viewer can immediately recognise peasant girls via long braids, as well as their boxy, often red, cotton jackets. The ready acceptance of these simple forms as representational suggests the normalisation of peasants in early PRC visual culture. In On the Way to Work, in particular, the relationship between the landscape and figures restores the ratio of traditional painting. The faceless, anonymous young women hold the same compositional importance as the contemplating scholar in premodern painting. Instead of a distinguished gentleman-scholar, the central figures are young women of modest means who have earned their value as artistic subjects in Maoist China through their industrious contribution to a socialist society.

Figure 9. Shi Lu 石魯, On the Way to Work (Shang gong 上工). 1961. Ink on paper. 16.5 x 11 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Figure 9. Shi Lu 石魯, On the Way to Work (Shang gong 上工). 1961. Ink on paper. 16.5 x 11 cm. Credit: Shi Dan.

Shi Lu continued to paint the familiar subject of peasant girls into the mid-1960s even as he undertook the creation of Eastern Crossing (Dong du 東渡, 1964), a major work that the artist considered a companion to Fighting in Northern Shaanxi (Hawks 2017: 173). In one such depiction, a girl is portrayed from the back, tilling with a hoe. Similar to On the Way to Work, this painting consists of few brushstrokes and relies on the viewers’ recognition of the subject’s red jacket and long braids to identify her as a peasant woman. The artist repeated the subject of the raking woman in other paintings, perhaps with a nod to Woman with Rake (1857) by the French realist painter Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), famous for his portrayals of French peasants. Without overstating the cross-cultural connection, Shi Lu seems to have drawn on foreign models for portraying peasants in forming a new genre for China.

The persistence by which Shi Lu painted peasant girls from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s shows the suitability of young peasant women as a dynamic subject for the visual culture of the PRC as a whole. It reveals the prolific nature of the artist’s practice, which saw continuous reinvention in style and medium through his personal experimentation with a variety of subjects. Still, it begs the question, while politically themed landscapes befitted Shi Lu’s status as an artist-cadre, why did the ideological position of young women, well established in Maoist discourse by the mid-1960s, remain a subject of interest for Shi Lu?

In a 1964 speech delivered at an exhibition organised by CAA Xi’an, Shi Lu (2003b) revealed his theories on the possibilities of figurative art. Exhibitions like this one were common for the CAA and showcased Xi’an artists’ works created during their recent visits to the countryside. As a senior member of the organisation, Shi Lu admonished his colleagues for creating sketches, though abundant, that lacked “explicitness” (mingque 明確) and “vividness” (shengdong 生動). He also made an unexpected reference to a seminal notion in traditional Chinese painting, “spirit resonance” (qiyun shengdong 氣韻生動), the most discussed and arguably important principle of Xie He’s Six Principles of Painting, penned in the sixth century.[14] Although these ideals can be variously interpreted, the emphasis on concept, rather than form or subject, departed from established principles of socialist realism, an imported Soviet style that would become the artistic standard during the Cultural Revolution. Shi Lu concluded the speech by distinguishing between several kinds of figural art to emphasise the breadth and richness of the figural painting genre. In keeping with Maoist expectations for cultural workers undergoing ideological training in the Chinese countryside, as these visits provided, Shi Lu called on his colleagues to reflect “deeply” and “broadly” on their experiences in the countryside in order to achieve vividness in their work. Like all texts produced in an official context during the Maoist period, the speech must be understood as Maoist orthodoxy delivered by an artist-cadre. At the same time, these textual formulations offer insight on how young peasant women remained a mainstay subject for Shi Lu as an open-ended theme into which he imported a range of formal and theoretical explorations.

The ubiquity of young peasant women in Shi Lu’s art aligns with Evans’s observation that, in propaganda images, women were most frequently portrayed as peasants while men were portrayed as workers and soldiers (1999: 72). In her study of rural Shaanxi women, Hershatter (2011) examines this peculiar intersection of gender and class. She argues that by inhabiting two spheres of socialist transformation – women and the peasantry – female peasants were still treated as “objects” of revolutionary change despite a degree of agency gained by essential labour in China’s economic development. Relatedly, Chen argues that the remaking of women and the peasantry as agents of sociopolitical change under Maoism are entwined: “Women in different guises and social positions haunted the very formation of peasant as a category” (2011: 73). Established in Maoist revolutionary theory as it was in visual art, the female peasant was an ideal subject for the CCP’s ideological enlightenment and embodied greater potential revolutionary transformation than any other social category.

Images of female peasants harnessed well-established global artistic traditions for portraying young women as the site of ideals. Although the state supported a limited range of artistic production in villages, the paintings that depict rural women in this discussion were produced by urban-based artists for urban audiences, thereby revealing an economically imbalanced urban-rural divide in which art acted as the liaison. These images fostered state-promoted empathy for peasants by the artists and by proxy, their intended urban viewers. At the same time, these images also fulfilled a type of paternalistic voyeurism that restored women as objects of desire and idealisation within the long global history of their representation, outside of state policy. Thus, even though the wide integration of peasants as artistic subject matter constituted a jarring shift in Chinese visual culture in the early PRC, the alignment of this new type of figural painting to existing visual traditions eased the transition.

Through Western idioms: Peasant women as socialist allegories of national progress

Beyond their basis in Chinese art history and Shi Lu’s personal theories, images of young peasant women emerged as an ideal symbol of socialist China for their ubiquity in global art traditions that influenced Chinese art throughout the twentieth century. Notable Republican artists such as Xu Beihong 徐悲鴻 (1895-1953), Lin Fengmian 林風眠 (1900-1991), Liu Haisu 劉海粟 (1896-1994), and Pan Yuliang 潘玉良 (1895-1977) embraced the female nude as a hallmark of modernity (Teo 2016; Wangwright 2020).[15] Xu’s Sound of the Flute (Xiao sheng 簫聲, 1926), for example, is noted for combining the realism of oil painting with the lyricism of ink painting. It is in this painting that we can find some precedent for the type of allegory that Shi Lu’s paintings of peasant girls would employ: a type of figural painting that focused more on the concept of the female form as an anchor for extrinsic meaning rather than on physical forms from which meaning was generated. At the same time, May Fourth activism inspired the politicisation of art. Disenfranchised figures, particularly suffering mothers, began appearing as a parallel category of female figures (Publow 2002). These early politicised portrayals of women set the stage for the full-fledged politicisation of the female figure in the communist period. The influence of socialist realism via Sino-Soviet exchange also made its mark on Chinese visual tradition (Andrews 2009: 53-69). The realistic depiction of the human figure, particularly female, signified not only Chinese modernity but also a commitment to the Socialist International.

In essence, a new type of figural tradition emerged in the PRC that tapped into broad Western art traditions of realism, romanticism, and allegory, which Chinese artists harnessed for political purposes. In Western traditions, allegorical art generally employs figures – usually women – to personify abstract concepts such as beauty, love, or nation. Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) and the Statue of Liberty are two famous examples of allegorical art, a genre rooted in the figural traditions of classical antiquity that gained prominence alongside the French academic style. The industrious peasant girl was a convergence of these currents in twentieth-century Chinese art. Prior to the mid-twentieth century, the use of the body as personification of conceptual ideals was a new and undeveloped practice in China, particularly in the ink medium. The female form represented virtues but only within the perimeters of Confucian ideals; she was a constituent of rather than a representation of China. Paintings such as Shi Lu’s Carrying Coal pivoted from tradition by adopting global artistic traditions to offer an eclectic blend of observed, ethnographic detail and projected idealisation of industrial labour onto figural form. Such depictions of young peasant women functioned as allegories of socialist modernity that embodied ideals of cultural purity, industriousness, and social change.

It would be an overstatement, however, to suggest that artistic portrayals of young peasant women were done in lockstep with the state’s political agenda. Describing the inspiration for painting a woman, the artist Jia Yong 笳詠 (1929-2004), Shi Lu’s colleague at CAA Xi’an, revealed the aspect of pleasure for male artists. Jia recounted seeing a young peasant woman hoeing the field when he and fellow Xi’an artists travelled along a mountain road in their jeep: the day was hot; to cool off, the girl had rolled up her shirt to the top of her chest, thinking she was alone. She was startled by the passing vehicle but did not have time to cover herself from the leering gaze of the male artists. This sight left an impression on Jia as he later painted the scene from memory. He compared his work to nude paintings in the Western tradition but distinguished it from them by justifying his employment of nudity in the context of celebrating labour and the subject’s “chaste purity” (1990: 243-8). The voyeuristic pleasure gained by the male artists in this story is obvious and would have been considered illicit if not for the artists’ lack of premeditation. The context of this episode was further condoned through the practice of “collecting folk customs” (caifeng 采風), an activity expected of cultural workers that required them to travel to rural areas to conduct ethnographic observation for inspiration.[16] In the words of Mulvey, the experience of the artist as the pleasure-seeking voyeur, although unplanned, marks his gaze as the “active/male” power in an imbalance that removes power from the “passive/female” subject and renders her the vessel of male desire (1999: 837-43). Stories like Jia’s, told through the perspective of an urban professional, are reminiscent of recollections of sexual exploits told by sent-down youths during the Cultural Revolution.[17] These coming-of-age stories functioned similarly as paintings by city-based artists in imagining the Chinese countryside as an escape from the confines of heterosexual, marital sexual norms found in urban spaces.

While politicised landscape painting extended a long tradition in Chinese art, the retention of the female form as the object of a presumed male gaze may seem to contradict the Maoist slogan that “women hold up half the sky.” Indeed, official promotion of gender equality did not necessarily translate into improved conditions for women (Andors 1983; Johnson 1983; Stacey 1983; Wolf 1985). In the realm of art, despite major shifts in how artists worked in the early PRC, their lifestyle during this period effectively prohibited change to gender norms, and women artists constituted a small percentage of state-employed artists in this period of supposed gender equality (Andrews 2020). Despite profound social changes, Chinese society remained conservative in terms of social codes of behaviour. The core group of artists in Xi’an were all men, as they were across China. One could argue the integration of women artists in communal settings would have presented logistical difficulties in a society that upheld gender norms.[18] Instead, Maoist art promoted the subject of women as a corrective to this imbalance and approved of peasant girls as one of the most common subcategories. Despite significant changes for women in post-1949 China, young women remained a preferred subject for artists even though their identities transformed from “beauties” to productive members of a socialist society.

Emphasised for their health and wholesome beauty unblemished by their working roles, young women fulfilled the dual purpose of embodying labour and symbolising the communist state’s advancement of women’s status. At the same time, the wholesomeness of these young healthy women suggested their reproductive viability even if such qualities were not explicitly portrayed. Socialist-appropriate for their embodiments of quotidian life, images of young women nevertheless evoked the sympathy of the paternalistic gaze. Unlike portrayals of androgynous “iron women,” these early-PRC images do not challenge gender norms. Shi Lu’s peasant girls are analogous to peasant heroines in model theatre, factious spaces that Di (2010) describes as a “feminist utopia” in which women are liberated from their domestic roles. While the painted space differs from the narrative space of theatre, the female subjects that occupied them are similar in retaining the conventional femininity associated with their peasant status.

Despite these new examples of figural allegory, the modern Chinese nation was still more commonly symbolised by landscape. This Land So Rich in Beauty (Jiangshan ruci duo jiao 江山如此多嬌, 1959) by Fu Baoshi 傅抱石 and Guan Shanyue 關山月 remains the preeminent example of a symbolic landscape with clear nationalistic content. Based on a verse of Mao’s poem “Snow,” the painting is a fictitious composite of different locations that aimed to encapsulate the vast geography of China.[19] Shi Lu, likewise, embraced this idiom, as, for instance, in his own large-scale symbolic landscape featuring Maoist ideology, the aforementioned Fighting in Northern Shaanxi. That this work was made in the same year as both Carrying Coal and Clever Girl Embroidering the Landscape speaks both to his own artistic talents and interests, and to the contemporaneous shifts in Chinese art outlined here. Shi Lu’s ability to paint both landscape and figures redefined previously established boundaries between the genres and shows how the figural form was no longer marginalised. While satisfying the political needs of the state, Shi Lu adopted non-indigenous artistic traditions for ink painting to contribute to a new Chinese figural tradition that expanded the global perimeters of allegorical art.

Conclusion: Gender and blind spots in Chinese art history

He Duoling’s 1981 The Spring Breeze is Awake (Chunfeng yi suxing 春風已甦醒)[20] is a product of the post-Maoist period in which visual and political traditions of the previous period are disrupted. In this celebrated painting, a young village girl sits in a field of coarse grass with a water buffalo and a puppy. The painting’s youthful subjects and the implied spring season evoke the sentiment of national renewal on an undetermined path. Similar to earlier depictions of peasant girls, this figure is chaste, nature-bound, and girlish; however, unlike them, her inactive and frail body appears even more vulnerable through the painting’s notable similarity to American painter Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World (1948), a portrait of a physically disabled girl (Ruan 2010: 30-3). The Spring Breeze is Awake is a dual revision of the socialist visual legacy: a retreat from the able-bodied yet feminine allegories of the high socialist era and the use of sentimental realism that departed from the exaggerated optimism of Chinese socialist realism; a “truer” reality without a progressive narrative, one that builds on earlier informal works such as those by Shi Lu.

The destabilisation of the anonymous peasant subject matter in the post-Mao period highlights its temporal limitations. As China detached itself from the political climate of the high socialist era and pivoted to a market-based economy, the symbolic virtues of the countryside lost their narrative potency. Peasant girls no longer evoked socialist ideals delivered through the visual vehicle of sexual desire and paternalistic longing. If anything, the harsh realities of rural life, encumbered by its economic difficulties, conjured pity if not a general dismissal of Maoist-era cultural productions that romanticised rural China and projected onto its inhabitants’ political ideals that supported social stability and economic growth. As this article has explored, however, the young female peasant was an ideal subject for visualisation and popularisation because it embodied a symbolic transformation from an oppressive society to one that seemed to place more agency in her hands (and body). Closer inspection reveals that these depictions upheld both indigenous and foreign visual traditions that objectified women as voyeuristic subjects and generalised them as anonymous ideals.

Visual portrayals of peasant women rarely transcended the objectification of their bodies even if their identities were modern, belying their vital roles in China’s socialist transformation. As anonymous embodiments of ideals, the female subjects are further stripped of any identity, even if they are represented as active, working women. Their muteness in contrast to their high visibility confirms even more that rural women, despite their double-possessed revolutionary potential, still existed as vessels for externally attributed ideals in a paternalistic society. Once interpreted, the non-linear, coded complexity of visualisations underscores the uneven legacy of Mao’s liberation of women.

As this article tends to show, gender remains a blind spot in the study of socialist Chinese art and visual culture. What little can be gathered about these images generally inform us more about the image-producers and the perimeters in which they worked than about the subjects themselves. The greater barrier in our vision, however, may be that images of women are so commonplace in the expansive global history of art that the appearance of young peasant women in modern Chinese art descends deeper into our blind spots and affirms our complicit understanding of the female subject. The goal of this article was to propose another orientation concerning alternative possibilities for analysing gender in modern Chinese art.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Getty/ACLS Postdoctoral Fellowship in the History of Art, and grants from the University of Colorado Denver Office of Research Services and the College of Arts & Media. I am grateful to Chang Liu, Coraline Jortay, and Jennifer Bond, organisers of the 2019 China Academic Network on Gender Conference. This article benefitted from conversations with Jennifer Altehenger, Doris Sung, Rebecca Karl, and Gail Hershatter, and written comments from Harriet Evans, Elizabeth Pugliano, and two anonymous reviewers.

Yang Wang is Assistant Professor of art history at the University of Colorado Denver. Her research examines the interplay between regionalism, indigeneity, and modernity in the art of socialist China. University of Colorado Denver, College of Arts & Media, 1201 5th Street, AR 177, Denver, CO 80204, United States (yang.wang@ucdenver.edu).

Manuscript received on 19 August 2020. Accepted on 28 September 2021.

Primary sources of displayed figures

China-Egypt Friendship Association 中國埃及友好協會. 1957. 趙望雲, 石魯埃及寫生畫選集 (Zhao Wangyun, Shi Lu Aiji xiesheng hua xuanji, Selected Sketches of Egypt by Chao Wang-yun and Shih Lu). Xi’an: Chang'an meishu chubanshe.

Guangdong Museum of Art 廣東美術館. 2007. 於無畫處筆生花 – 石魯的時代與藝術 (Yu wuhua chu bi shenghua – Shi Lu de shidai yu yishu, Nowhere to Draw Flowers – Shi Lu’s Time and His Art). Shijiazhuang: Hebei jiaoyu chubanshe.

MOWRY, Robert D. 2011. The Beauty of Art: Paintings and Calligraphy by Shi Lu: From the Private Collection of Robert Hatfield Ellsworth. New York: Christie’s.

SHI, Dan 石丹. 2003. 中國名畫家全集 – 石魯 (Zhongguo minghuajia quanji – Shi Lu, Complete Collection of Chinese Famous Painters – Shi Lu). Shijiazhuang: Hebei jiaoyu chubanshe.

References

ALTEHENGER, Jennifer. 2018. Legal Lessons: Popularizing Laws in the People's Republic of China, 1949-1989. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center.

ANDORS, Phyllis. 1983. The Unfinished Liberation of Chinese Women, 1949-1980. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

ANDREWS, Julia F. 1995. Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

——. 2009. “Art Under Mao: ‘Cai Guoqiang’s Maksimov Collection’ and China’s Twentieth Century.” In Josh YIU (ed.), Writing Modern Chinese Art: Historiographic Explorations. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum. 53-69.

——. 2020. “Women Artists in Twentieth-century China: A Prehistory of the Contemporary.” Positions Asia Critique 28(1): 19-64.

ANDREWS, Julia F., and Kuiyi SHEN (eds.). 1998. A Century in Crisis. Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-century China. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications.

BAILEY, Paul J. 2012. Women and Gender in Twentieth-century China. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

BENTLEY, Tamara. 2012. The Figurative Works of Chen Hongshou (1599-1652): Authentic Voices/Expanding Markets. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

BRAZINSKY, Gregg. 2017. Winning the Third World: Sino-American Rivalry during the Cold War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

BROWN, Jeremy. 2008. Crossing the Rural-urban Divide in Twentieth-century China. PhD Dissertation. San Diego: University of California.

CHEN, Tina Mai. 2003. “Propagating the Propaganda Film: The Meaning of Film in Chinese Communist Party Writings, 1949-1965.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 15(2): 154-93.

——. 2011. “Peasant and Woman in Maoist Revolutionary Theory, 1920s-1950s.” In Catherine LYNCH, Robert MARKS, and Paul PICKOWICZ (eds.). Reform, Revolution, and Radicalism in Modern China, Essays in Honor of Maurice Meisner. Lanham: Lexington Books. 473-91.

CHEN, Xiaomei. 1999. “Growing Up with Posters in the Maoist Era.” In Harriet EVANS, and Stephanie DONALD (eds.), Picturing Power in the People’s Republic of China: Posters of the Cultural Revolution. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. 101-22.

CHUNG, Anita (ed.). 2011. Chinese Art in an Age of Revolution: Fu Baoshi (1904-1965). New Haven: Yale University Press.

CLARKE, David. 2019. China-Art-Modernity: A Critical Introduction to Chinese Visual Expression from the Beginning of the Twentieth Century to the Present Day. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

COHEN, Myron L. 1993. “Cultural and Political Inventions in Modern China: The Case of the Chinese ‘Peasant.’” Daedalus 122(2): 151-70.

DI, Bai. 2010. “Feminism in the Revolutionary Model Ballets the White-haired Girl and the Red Detachment of Women.” In Richard KING (ed.), Art in Turmoil: The Chinese Cultural Revolution, 1966-76. Vancouver: UBC Press. 188-202.

DIKÖTTER, Frank. 2010. Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-1962. New York: Walker and Company.

EVANS, Harriet. 1993. “Images of Chinese Women in the 1990s.” Britain-China 53(3): 6-9.

——. 1995. “Defining Difference: The ‘Scientific’ Construction of Sexuality and Gender in the People’s Republic of China.” Signs 20(2): 357-94.

——. 1999. “‘Comrade Sisters’: Gendered Bodies and Space.” In Harriet EVANS, and Stephanie DONALD (eds.), Picturing Power in the People’s Republic of China: Posters of the Cultural Revolution. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. 63-78.

——. 2000. “Marketing Femininity: Images of the Modern Chinese Woman.” In Timothy B. WESTON, and Lionel M. JENSEN (eds.), China Beyond the Headlines. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. 217-44.

FLATH, James A. 2004. The Cult of Happiness: Nianhua, Art, and History in Rural North China. Vancouver: UBC Press.

GALIKOWSKI, Maria. 1996. Art and Politics in China, 1949-1986. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

GLADNEY, Dru C. 1994. “Representing Nationality in China: Refiguring Majority/Minority Identities.” The Journal of Asian Studies 53(1): 92-123.

HAWKS, Shelley Drake. 2017. The Art of Resistance: Painting by Candlelight in Mao's China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

HERSHATTER, Gail. 2011. The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China’s Collective Past. Berkeley: University of California Press.

——. 2019. Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

HU, Xiaoyan. 2021. The Aesthetics of Qiyun and Genius Spirit Consonance in Chinese Landscape Painting and Some Kantian Echoes. Lanham: Lexington Books.

IP, Hung-yok. 2003. “Fashioning Appearances: Feminine Beauty in Chinese Communist Revolutionary Culture.” Modern China 29(3): 329-61.

JIA, Yong 笳咏. 1990. 笳詠書畫集 (Jia Yong shu hua ji, Jia Yong’s Calligraphy and Painting Collection). Xi’an: Shaanxi renmin meishu chubanshe.

JOHNSON, Kay Ann. 1983. Women, the Family, and Peasant Revolution in China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

KO, Dorothy. 1994. Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-century China. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

LAING, Ellen Johnston. 1988. The Winking Owl. Berkeley: University of California Press.

——. 2004. Selling Happiness: Calendar Posters and Visual Culture in Early-twentieth-century Shanghai. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

LI, Yifan. 2019. “Representing Female Sales Associates in Post-Mao Propaganda Posters.” Paper presented at The Association for Asian Studies Conference; Denver, United States, 24-27 March 2019.

LU, Hanchao. 1999. Beyond the Neon Lights: Everyday Shanghai in the Early Twentieth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

LUFKIN, Felicity. 2016. Folk Art and Modern Culture in Republican China. Lanham: Lexington Books.

MAO, Zedong. 1966. Quotations from Mao Tse-Tung. Beijing: Foreign Language Press.

MULVEY, Laura. 1999. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In Leo BRAUDY, and Marshall COHEN (eds.), Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 833-44.

NG, Chun Bong, Cheuk Pak TONG, Wong YING, and Yvonne LO. 1996. Chinese Woman and Modernity: Calendar Posters of the 1910s-1930s. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing.

NOTH, Juliane. 2009. Landschaft und Revolution: Die Malerei von Shi Lu (Landscape and Revolution: Shi Lu’s Painting). Berlin: Reimer.

PANG, Laikwan. 2014. “The Visual Representations of the Barefoot Doctor: Between Medical Policy and Political Struggles.” Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 22(4): 809-36.

PUBLOW, Erin. 2002. Mothers and Sons: A Gender Study of the Modern Chinese Woodcut Movement. Master’s Thesis. Ohio: Ohio State University.

RUAN, Xudong. 2010. “‘Contemplative Painting’ in China and Andrew Wyeth.” In Wu HUNG, and Peggy WANG (eds.), Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents. New York: Museum of Modern Art. 30-3.

SHAPIRO, Judith. 2001. Mao's War against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SHI, Lu 石魯. 2003a. “頂天立地的女人們 – 印度寫生隨感之一” (Ding tian li di de nürenmen – Yindu xiesheng suigan zhi yi, Indomitable Women – Impressions from Sketching in India). In YE Jian 葉堅, and SHI Dan 石丹 (eds.), 石魯文集 (Shi Lu wen ji, Shi Lu’s Collection). Xi’an: Shaanxi renmin meishu chubanshe. 35-6.

——. 2003b. “關於人物畫問題” (Guanyu renwuhua wenti, On the Issue of Figural Painting). In YE Jian 葉堅, and SHI Dan 石丹 (eds.), 石魯文集 (Shi Lu wen ji, Shi Lu’s Collection). Xi’an: Shaanxi renmin meishu chubanshe. 187-9.

SHIH, Shu-mei. 2007. “Shanghai Women of 1939: Visuality and the Limits of Feminine Modernity.” In Jason KUO (ed.), Visual Culture in Shanghai, 1850s-1930s. Washington: New Academia. 190-210.

STACEY, Judith. 1983. Patriarchy and Socialist Revolution in China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

SULLIVAN, Michael. 1996. Art and Artists of Twentieth-century China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

TEO, Phyllis. 2016. Rewriting Modernism: Three Women Artists in Twentieth-century China: Pan Yuliang, Nie Ou and Yin Xiuzhen. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

VINOGRAD, Richard. 1992. Boundaries of the Self: Chinese Portraits, 1600-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

VOLLAND, Nicolai. 2017. Socialist Cosmopolitanism: The Chinese Literary Universe, 1945-1965. New York: Columbia University Press.

WANG, Yang. 2019. “Envisioning the Third World: Modern Art and Diplomacy in Maoist China.” ARTMargins 8(2): 31-54.

WANGWRIGHT, Amanda. 2020. The Golden Key: Modern Women Artists and Gender Negotiations in Republican China (1911-1949). Leiden: Brill.

WHITE, Julia (ed.). 2017. Repentant Monk: Illusion and Disillusion in the Art of Chen Hongshou. Berkeley: University of California Press.

WOLF, Margery. 1985. Revolution Postponed: Women in Contemporary China. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

WONG, Aida Yuen (ed.). 2012. Visualizing Beauty: Gender and Ideology in Modern East Asia. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

WRIGHT, Tim. 2010. The Political Economy of the Chinese Coal Industry: Black Gold and Blood-stained Coal. London: Routledge.

YE Jian 葉堅, and SHI Dan 石丹 (eds.). 2003. 石魯文集 (Shi Lu wen ji, Shi Lu’s Collection). Xi’an: Shaanxi renmin meishu chubanshe.

ZHENG, Jane. 2009. “The Shanghai Fine Arts College: Art Education and Modern Women Artists in the 1920s and 1930s.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 19(1): 192-235.

——. 2016. The Modernization of Chinese Art: The Shanghai Art College, 1913-1937. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

[1] Please refer to the primary sources at the end of the article for the full references of the figures displayed in this paper.

[2] See Flath (2004) for a discussion on the politicisation of nianhua.

[3] Altehenger (2018: 89-126) discusses the harnessing of propaganda art as an educational tool for the Marriage Law.

[4] Other images of the time similarly promoted marital freedom or offered legal guidance, see for example https://chineseposters.net (accessed on 29 October 2021).

[5] Late-Ming artist Chen Hongshou 陳洪綬 and late-Qing artist Ren Xiong 任熊 are credited with establishing the genre of self-portraiture in Chinese visual tradition. See Bentley (2012) and White (2017) for discussions on Chen Hongshou, and Vinograd (1992) for a broader discussion on Chinese self-portraits.

[6] The growing visibility of the female form in the Republican era as signifiers of urban-based modernity is discussed in Ng et al. (1996), Laing (2004), Shih (2007), Wong (2012), Wangwright (2020). See Zheng (2016) for a discussion on the Republican-era art education.

[7] Laing (1988), Andrews (1995), Galikowski (1996), and Sullivan (1996) remain authoritative studies on art produced by establishment artists of the PRC, but they do not discuss gender at length.

[8] Andrews discusses regional art that features minority women (1995: 250-76) and Gladney (1994) offers a general discussion of Han representations of minorities.

[9] As the vice chairman of the work unit (danwei 单位), he led its six ink painters to national recognition in the early 1960s through a series of prominent exhibitions. The group would eventually be known as the Chang’an School (Chang’an huapai 長安畫派), a name that honoured the artists’ geographical location and efforts in modernising the traditional practice of ink painting (guohua 國畫) by transforming it from a studio-based practice to a hybrid genre that combined the Chinese ink medium with Western conventions based on real-life observation.

[10] Noth (2009) focuses on the political dimension of Shi Lu’s landscapes while Hawks (2017) discusses the artist in the context of the political persecution he suffered during the Cultural Revolution. A monographical exhibition at the Museum of New Zealand has been the only solo exhibition on Shi Lu outside of China: Shi Lu: A Revolution in Painting, 22 March – 22 June 2014, Te Papa Museum, Wellington, New Zealand. Much of the American interest in Shi Lu was spearheaded by American collector Robert Ellsworth through his donations to major North American collections. An essay by Robert D. Mowry in a related catalogue provides historical context to an otherwise formalist treatment of Shi Lu’s work: Robert D. Mowry, The Beauty of Art: Paintings and Calligraphy by Shi Lu: From the Private Collection of Robert Hatfield Ellsworth, March 2011, New York: Christie's.

[11] Although Shi Lu was also a theorist who wrote and spoke extensively on conceptual matters such as the basis of creation, aesthetics, and national forms, his known texts do not reveal formulations regarding his peasant subjects.

[12] Coloured cotton tops with a crossover toggle closure identified wearers as peasants in Maoist China, according to Chen (2003: 172).

[13] Boosting China’s coal production was a top priority of the “Little Leap Forward” in 1956 and the Great Leap Forward (1958-1961). Various publications discuss the economic and environmental detriment of the latter, including Shapiro (2001), Dikötter (2010), and Wright (2010).

[14] An overview of various translations of qiyun shengdolaurang is provided in Hu (2021: 16-9).

[15] Andrews and Shen (1998) discuss the approaches of early twentieth-century Chinese artists while the context of China “looking West” is covered in Clarke (2019: 33-53).

[16] See Lufkin (2016) regarding the integration of “folk culture” into mainstream national culture.

[17] Among various examples, Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress is a semi-autobiographical novel about the sexual relationship between a peasant girl and two male sent-down youths: Dai Sijie, Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, 2002, New York: Anchor Books.

[18] Official artists in China were predominately male. In Xi’an, the all-male group of artists at the CAA relied on their wives for administrative and household support. The subject of women’s invisible labour and contributions to the urban work sphere deserves further research but is outside of the scope of this article. For a discussion on women artists in the context of art institutions in the Republican period, see Zheng (2009).

[19] The painting’s complex creation process and hybridised Chinese-Western style are discussed in Andrews (1995) and Chung (2011).

[20] Painting available on http://www.namoc.org/xwzx/zt/xj/zp/201403/t20140305_274298.htm (accessed on 16 December 2021).