BOOK REVIEWS

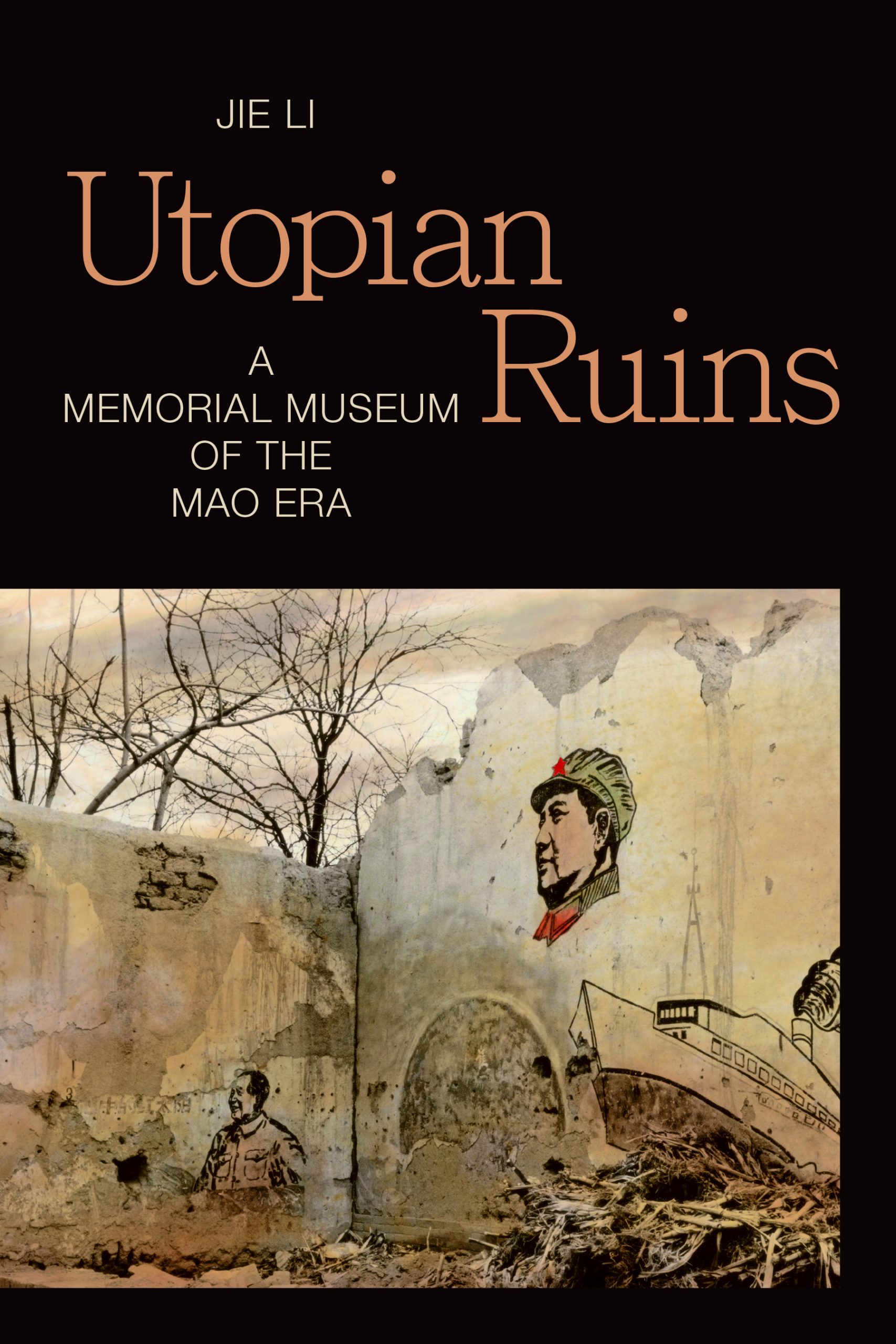

LI, Jie. 2020. Utopian Ruins: A Memorial Museum of the Mao Era. Durham: Duke University Press.

Li Jie’s new book is an intriguing study of a series of objects that can be understood as cultural texts in a broad sense, spanning literary writings, photographs, documentary films, and architectural constructions. Produced during the Mao era, they have recently been “re-mediated,” as Li writes, or reintroduced into China’s media sphere, whether through journalism, independent film production, or museum-making. The study presents itself as a “memorial museum,” a “curated collection” of exhibits assembled by the author around the theme of “utopian ruins.” Rather than excavating new primary sources, “this imagined memorial-museum-in-book-form curates from existing textual, photographic, and cinematic records about the subaltern” (p. 6). The common theme of these texts is determined by the author’s choice to include both utopia and ruins, the socialist ideals of Maoism as well as the violence and mass mortality it entailed.

Li Jie’s new book is an intriguing study of a series of objects that can be understood as cultural texts in a broad sense, spanning literary writings, photographs, documentary films, and architectural constructions. Produced during the Mao era, they have recently been “re-mediated,” as Li writes, or reintroduced into China’s media sphere, whether through journalism, independent film production, or museum-making. The study presents itself as a “memorial museum,” a “curated collection” of exhibits assembled by the author around the theme of “utopian ruins.” Rather than excavating new primary sources, “this imagined memorial-museum-in-book-form curates from existing textual, photographic, and cinematic records about the subaltern” (p. 6). The common theme of these texts is determined by the author’s choice to include both utopia and ruins, the socialist ideals of Maoism as well as the violence and mass mortality it entailed.

The first two chapters deal with textual documents produced by two famous writers, Lin Zhao 林昭and Nie Gannu 聶紺弩, who were persecuted and imprisoned during the Anti-rightist Movement and the Cultural Revolution, respectively. Focusing on Lin Zhao’s prison essays and notebooks, many of them written in blood, Li Jie argues that Lin drew on a tradition of premodern and revolutionary martyrology, in which blood stands for both the “promises and dangers of revolution” (p. 66). In the case of Nie Gannu, several of his poems found their way into his secret “dossier” (dang’an 檔案) together with “interpretations” penned by people reporting on him and, ironically, survived thanks to the dossier.

The second section of the book draws on photography and documentary films produced during the Mao era. Propaganda photography, theorised by the journal Mass Photography (1958-1960), is discussed as “eyewitness testimonies to revolutionary miracles that not only failed to witness and record but also contributed to man-made catastrophes” (p. 105). Nonetheless, photography deserves a place in the memorial museum: “Rather than dismissing propaganda photos or treating them as objective windows onto a historical past, we should recognize both the aspirations they express and their complicity in the catastrophe” (p. 147).

The moving images produced by Michelangelo Antonioni in his film Chung Kuo: Cina (1972) and Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan in their epic How Yukong Moved the Mountains (1976) evince similar ambiguities. Li Jie argues that the directors “went to China in search of an authentic world where social relations were not mediated by mass-produced images, only to find another kind of ‘society of spectacle’ where the Maoist visual regime penetrated the most remote villages” (p. 167). Despite their shortcomings, the films stand as documents to the age, Li Jie argues, that were avidly discovered by nostalgic Chinese audiences in the early 2000s.

The final section of the book deals with architectural and monumental productions or legacies of the Mao era. Here the book covers some well-known ground, with the depiction of factories in three films: Wang Bing’s 王兵 West of the Tracks (Tie xiqu 鐵西區), Jia Zhangke’s 贾樟柯 Twenty-four City (Ershisi cheng ji 二十四城記), and Zhang Meng’s張猛 Piano in a Factory (Gang de qin 鋼的琴). The factory serves as an ambiguous metaphor of the Mao era, which elicits both the nostalgia of some of the retired workers interviewed by Jia Zhangke, but also the enduring effects of industrial pollution and perennial disenfranchisement in Wang Bing’s film.

The last chapter examines existing museums and memorials of the Mao era, beginning with a careful discussion of Ba Jin’s 巴金 1986 essay calling for a museum of the Cultural Revolution, and surveying some of the sites that can make a claim to fulfilling such a mission. Ultimately, Jianchuan’s Museum Cluster, with its cluttered, uncommented, yet immediately accessible and even tangible mass-produced content, may allow “more pluralistic interpretations of the past than any historical master narrative” (p. 247). By contrast, former “trauma sites” like the prison camp at Jiabiangou, a refurbished May Seven cadre school in Hubei, or the Red Guard graveyard in Chongqing, and to a lesser degree the lone Cultural Revolution Museum in Shantou, remain largely inaccessible – on several levels – to the public.

Li Jie’s study provides a rich and thought-provoking account of the cultural texts she has chosen to focus on and highlights the many-layered ambiguities inherent in today’s remembrances of the Mao era. Some of these ambiguities perhaps deserve to be teased out more fully. This reviewer remains somewhat doubtful about both the object “utopian ruins” and the chosen form of a “curated exhibit.” Certainly, Maoist ideology can be described as informed by certain utopian philosophies (although these might be spelled out more precisely). However, the systematic attempt to strike a balance between utopian idealism and violent or destructive outcomes often seems contrived. Do we really need to connect literary inquisitions with a “utopian quest to purify the ranks of ‘the People’” (p. 69), or can we recognise that there are sincerely held but destructive and anti-humanistic views at the foundation of the Maoist project and socialism more generally? The word “dystopian,” incidentally, only appears once or twice in the book, and always to characterise a “reality” that is contrasted with a “utopian vision” (p. 63). Portraying socialism as mainly a ruined ideal seems at best an oversimplification.

Similar questions are raised by the method of selective “curating.” Although it is true that historical “objects” can be studied together with their “re-mediation” as memory in the present, the objects themselves are not quite the same in different parts of the book. The literary and visual texts produced during the Mao era and discussed in the first two parts are studied in their original contexts before they are “re-mediated”; by contrast, the factories and prison camps are studied only through their re-mediation and lack original context.

Finally, while the study mobilises an army of references from literary and cultural studies, cameo appearances by Agamben, Badiou, Barthes, Derrida, Žižek, and others add little substance, producing a scattered effect and deterring from the main argument rather than reinforcing it. By contrast, it is regrettable that the study does not engage more systematically with the renewed historical production on the Mao era that has appeared over the last decades, both in China and abroad. For example, Gao Hua’s study How the Red Sun Rose (2019) is conspicuously absent from the discussion on ideology, and although Li’s book aims to investigate “subaltern” memories, it is largely based on the productions of intellectuals or other elites, while studies of grassroots groups like Yang Kuisong’s Eight Outcasts: Social and Political Marginalization under Mao (2019) or Guo Yuhua’s 郭于華 Shoukuren de jiangshu (受苦人的講述, The Narrative of the Sufferers, 2013) are not mentioned. As a result, Utopian Ruins sometimes lacks historical depth. Without further discussion, the post-Mao era is termed “post-socialist” despite the ubiquity of references to socialism in today’s media discourse. The larger arc of connections between the Republican, Mao, and post-Mao eras is also oversimplified when the book calls to reinvent the “public cultural practices” of the Mao era (p. 275), ignoring that these practices were themselves often violent and destructive deformations of civic practices that existed earlier in China’s modern history. While curation and history remain legitimately distinct projects, more engagement with historians might bring additional clarity to the book’s object and method.

Sebastian Veg is a professor of intellectual history of modern and contemporary China at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales. Centre de recherches historiques, EHESS, 54 boulevard Raspail, 75006 Paris, France (veg@ehess.fr).

References

GAO, Hua. 2019. How the Red Sun Rose. The Origin and Development of Yan’an Rectification Movement. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

GUO, Yuhua 郭于華. 2013. 受苦人的講述 (Shoukuren de jiangshu, The Narrative of the Sufferers). Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

YANG, Kuisong. 2019. Eight Outcasts: Social and Political Marginalization under Mao. Berkeley: University of California Press.