BOOK REVIEWS

Multi-sited Consumption in the Greater Bay Area: The Interplay of National Policies, Consumer Behaviours, and Urban Amenity Transformation

Xiangyi Li is Associate Professor at the School of Sociology and Anthropology, Sun Yat-Sen University, No. 135 Xingang Xi Road, Haizhu District, Guangzhou, China (lixy26@mail.sysu.edu.cn).

Zeyu Gong is a master’s student in sociology from the Department of Sociology, Peking University, No. 5 Yiheyuan Road, Haidian District, Beijing, China (2401211880@stu.pku.edu.cn).

Introduction

Cross-border consumption is not new in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA). Previously, it was common for Mainland people to shop in Hong Kong and Macao, buying everything from luxury items to essentials such as baby formula, a trend that sparked controversy as Hong Kong residents raised concerns over shortages caused by Mainland shoppers (Bergstresser 2022). In recent years, cross-border consumption has evolved into a two-way exchange, with more Hongkongers “heading north” to Shenzhen and beyond for shopping, leisure, and services, attracting considerable attention.[1] As the Greater Bay Area – recently coined to foster deeper economic integration and cultural exchange between Hong Kong, Macao, and major cities in Guangdong – is positioned as an integrated consumer market, cross-border consumption has become a symbol of the GBA’s vision to blend markets, lifestyles, and services across borders in unprecedented ways.

The development of infrastructure and streamlined border controls by central and regional governments has catalysed the emergence of an integrated urban cluster within the GBA. This urban cluster, characterised by interconnected GBA cities, fosters a unique economic and social ecosystem where cross-border movement is not only easier but encouraged. Despite reduced disparities in access and cost of goods and services across these cities, notable differences remain, which shape complex consumer behaviours. Consumers now utilise the GBA’s interconnected infrastructure to engage in multi-sited consumption by accessing specialised goods, healthcare, leisure, and more, tailored to each city’s strengths. This demand-driven, multi-sited approach has, in turn, spurred cities to cultivate distinctive urban cluster amenities – specialised services and experiences – to meet evolving consumer needs. The GBA urban cluster amenities thus exemplify a layered interaction between policy-led regional integration and organic, varied consumer demands, which result in a dynamic, multi-centred urban landscape.

Drawing on data from in-depth interviews, archival records, online interaction and other sources, this study focuses on the multidimensional interactions between national policies, individual consumer behaviours, and their collective impacts on urban cluster amenities in the GBA. We attempt to offer a depiction of everyday lifeworlds shaped by consumption activities across different cities, as well as the internal borders with both physical presence and evolving symbolic meanings in the context of the GBA’s development. The article also emphasises consumer agency in navigating multiple hyper mobile cross-border spaces and highlights the difficulties consumers encounter. Finally, this study finds how multi-sited consumption reshapes the transformation of urban amenities in various GBA cities. The findings of this research provide a more holistic view of cross-border dynamics and the diverse strategies employed by various border crossers in the GBA.

Literature review

Urban cluster amenities: A holistic approach to regional development

Cities within close geographical proximity often develop robust economic, social, and infrastructural linkages (Scott 2001). Fuelled by economic globalisation, advancements in transportation and communication technologies, as well as strategic regional development planning, these cities frequently form city clusters functioning as single, interconnected urban entities. Through labour specialisation, diversified consumer demand, increased population mobility, and enhanced intercity connectivity (Bertinelli and Black 2004), urban clusters are able to provide a wide range of amenities to enhance quality of life, convenience, comfort, and enjoyment, including physical infrastructures such as parks, libraries, hospitals, and schools, as well as services and cultural offerings such as dining options and recreational activities. Each city in the cluster contributes distinct amenities that align with its own strength (Collins 2012; Fang and Yu 2017).

Previous literature on urban amenities has mainly focused on their development within individual cities. However, as urbanisation expands beyond individual cities and encompasses entire regions, the focus of development has shifted towards the systemic and complementary nature of amenities across these regions (Clark and Murphy 1996). The consumers of these amenities thus increasingly view and utilise them holistically, in order to maximise the benefits offered by the entire region rather than a single city. Consequently, urban clusters are considered the proper unit for budgeting, distributing, and acquiring amenities, as intercity transportation systems effectively link cities and enable seamless access to shared resources across the clusters as in the Greater Bay Area (Costa and Kahn 2000; Scott 2008; Yan et al. 2022).

This research develops the concept of “urban cluster amenities,” emphasising an integrated, regional approach to urban development and planning (Vorley 2008; Shi et al. 2022). This concept highlights how cities within a cluster can coordinate their planning and resource allocation efforts to optimise amenities across the region. By sharing resources and services, urban clusters can enhance their overall functionality, accessibility, and liveability. This approach also allows urban clusters to offer amenities that may not be feasible within individual cities alone. Ultimately, this concept aims at describing an urban environment that caters to a wider range of needs across the cluster, supporting both regional integration and economic vitality (Martin and Sunley 2015; Carlino and Saiz 2019; Su, Hua, and Liang 2019; Feng, Lee, and Peng 2023).

The role of amenities in shaping mobility in urban clusters

Urban amenities significantly influence the employment, consumption, and other aspects of everyday lifeworlds of residents by shaping their daily activities, social interactions, and quality of life within urban environments (Faist 2013). On the one hand, amenities such as healthcare, education, and transportation are crucial for the production of everyday life because they provide essential resources that enable individuals to participate in the labour markets, as well as to access unique or high-paying job opportunities not available in less developed areas (Wang 2014). For example, access to quality healthcare services guarantees that patients can maintain their productivity and improve their economic prospects, while also offering well-respected jobs, such as doctors and nurses, which contribute to the economic well-being of individuals and vitality of the city (Arntz, Brüll, and Lipowski 2023).

On the other hand, urban amenities also influence the consumer behaviours of urban dwellers by providing a wide array of services and facilities that improve their quality of life (Tan and Li 2024). Amenities such as shopping centres, restaurants, recreational facilities, and cultural institutions are essential for the consumption aspect of everyday life, offering numerous options for the leisure, entertainment, and daily needs of residents with diverse preferences and lifestyles (Carlino and Saiz 2019). Moreover, by attracting both local consumers and those from elsewhere, amenities such as retail districts and dining establishments create bustling economic hubs that stimulate local economies and create jobs.

Existing studies primarily investigate the impacts of urban amenities on locals and migrants, such as families purchasing residence in cities with high-quality education or artists relocating to cities with ample cultural resources (Clark et al. 2003; Florida 2019; Villaneuva, Kidokoro, and Seta 2020). In an urban cluster, improved infrastructure and transportation technologies transform traditional dynamics by facilitating greater mobility across an entire region. Enhanced connectivity through high-speed rail, efficient public transit networks, and streamlined border managements can not only reduce the costs associated with intercity travel but also create a broader, interconnected marketplace of amenities (Xiang and Lindquist 2014). In this vein, residents across the GBA enjoy easier access to specialised amenities and services in multiple cities, which support a pattern of multi-sited consumption. This shift enables consumers to selectively engage with various amenities across the region, and the resulting movement across city boundaries redefines traditional consumption behaviours and fosters a dynamic, shared urban ecosystem that benefits from the strengths of each city (Urry 2007; Graells-Garrido et al. 2021).

Cross-border consumption and economic integration

The phenomenon of cross-border shopping and its impact on urban economies is well-documented, particularly in border regions with higher levels of economic integration, such as Europe. In many European border cities, retail and service sectors face strong competition from the cities across the border, where differences in prices or product availability create more attractive options for consumers (Anderson and O’Dowd 1999). Existing literature primarily explores the complex and nuanced effects of open borders on local economies in areas such as those between Germany and France, or Belgium and the Netherlands, where consumers frequently cross into neighbouring cities to take advantage of lower taxes, favourable exchange rates, or exclusive products and services unavailable at home (Leal, López-Laborda, and Rodrigo 2010; Boehmer and Peña 2012). This cross-border shopping pattern contributes to a complex politico-economic landscape in which local markets have been disrupted by fluid, cross-border consumer spending (Szytniewski and Spierings 2014; Tan and Chung 2023).

However, in other border regions, cross-border activities, including consumption, are highly regulated. Nation-states establish legal frameworks that control and restrict mobility due to security concerns, economic protectionism, or political sensitivities. In those regions, state-imposed visa requirements, tariffs, and border checks limit the ease of cross-border movement, and create distinct separations between two economies, which often hinder cross-border shopping and economic integration, as consumers face logistical barriers and higher costs associated with cross-border consumption (Newman 2020; Burstein, Lein, and Vogel 2024). Consequently, in regulated border areas, local economies remain more insular, with cities focusing primarily on domestic markets rather than competing for foreign consumers. This limited mobility can impact urban development and the types of amenities in which cities invest. In regions where cross-border mobility is tightly controlled, cities often lack the economic flexibility seen in more integrated border regions that benefit from greater economic growth (Paasi et al. 2018).

The Greater Bay Area represents a unique region where former national borders have gradually transformed into much more accessible internal boundaries. Historically, the borders between Hong Kong, Macao, and Mainland China were strictly regulated in a context of colonial control and geopolitical separation. However, even during the colonial era, economic pragmatism led to the gradual encouragement of cross-border activities as Hong Kong’s trade and manufacturing sectors heavily relied on labour, resources, and markets in the Mainland. In recent years, China’s central government has accelerated these economic integrations through policy initiatives designed to streamline border controls, enhance infrastructure, and promote regional cooperation within the GBA. As a result, this area is increasingly envisioned as a cohesive urban cluster where once-rigid borders now support a dynamic, unified economy that blends three subregions’ strength into a single, globally competitive entity. The development of tailored amenities in cities within the GBA that cater to both local and cross-regional needs enables consumers to engage in cross-border shopping more frequently.

The motivating factors behind multi-sited consumption in the Greater Bay Area

The Greater Bay Area, facilitated by streamlined border management and infrastructure development, is evolving from a set of distinct urban areas into a cohesive urban cluster, with local amenities also transforming into shared urban cluster amenities accessible across multiple cities. Such developments in regional mobility expand traditional cross-border consumption into newly emerging multi-sited consumption, where residents and visitors can access specialised goods, services, and experiences across various cities in the GBA in a single journey. However, understanding the motivations behind multi-sited consumption remains essential. Questions persist regarding why customers prefer one location over another and why they choose to connect certain cities in their journeys while bypassing others.

Consumers usually pursue three key values in consumption: functional, social, and hedonic. Functional value addresses practical utility and efficiency, providing tangible benefits and meeting basic needs. Social value, by contrast, involves expressing taste, status, power, and prestige, allowing consumers to convey their social identity within a community. Hedonistic values deliver aesthetic and psychological satisfaction, offering emotional fulfillment (Bourdieu 1984; Campbell 1987; Baudrillard 1998). In relating to these values, this research identifies three motivations behind multi-sited consumption: cost-effectiveness, uniqueness, and scarcity.

Cost-effectiveness motivates consumers to seek high-quality amenities at lower cost, driven by disparities in taxes, labour costs, and pricing structures across cities. This allows consumers to maximise functional value by capitalising on regional price differences, a practice known as “geographical arbitrage” (Hayes 2014). In regions such as the GBA, efficient infrastructure and streamlined customs make this strategy viable, while institutional differences help sustain the necessary price differentials (Baldwin and Wyplosz 2015). The GBA’s specific blend of administrative and economic systems across Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao provides fertile ground for such cross-border consumption opportunities. Uniqueness involves the pursuit of distinct and irreplaceable amenities tied to specific locations. In a postmodern economy that prioritises individuality and personal experiences, unique amenities cater to hedonistic needs by offering emotional and aesthetic satisfaction (Beckert 2016; Reckwitz 2020). This shift aligns with a growing preference for personalised and place-specific consumption, where distinctive regional characteristics reinforce the economic and cultural vitality of urban clusters. As consumers seek unique experiences, they contribute to the dynamism and diversity of urban spaces, underscoring the importance of maintaining cities’ distinctive identities within an urban cluster (Pine and Gilmore 1999; Zukin 2010). Scarcity relates to accessing limited, high-value resources that symbolise significant social prestige. High-quality amenities such as advanced healthcare or educational facilities are unevenly distributed and constrained by availability (Nshimbi 2019; Yan et al. 2022). This scarcity enhances the social value of amenities, as individuals who access these resources can effectively showcase their economic capability and social standing, therefore reinforcing existing social hierarchies. For many, consuming scarce amenities in other places is a means of constructing and expressing social identity and status, elevating the perceived exclusivity and prestige of these resources (Wang and Lo 2007; Beckert 2016).

It is important to note that these values often overlap; a single amenity may provide multiple types of value and attract consumers for different reasons. For example, an amenity can be both affordable and scarce, which maximises functional value while also delivering social value by conferring status and exclusivity. This overlap illustrates the complex interplay of values in multi-sited consumption, where strategic selection of amenities allows consumers to meet their multiple needs and aspirations simultaneously.

The analytical framework for multi-sited consumption in the Greater Bay Area

This analytical framework integrates macro-, meso-, and micro-level dynamics to explain how cross-border consumption is shaped and evolves in this region. At the macro-level, governmental initiatives, including physical infrastructure development, streamlined border processes, and institutional collaboration, foster the buildup of urban cluster amenities and enhance cross-border mobility. These policies lay the groundwork for increased connectivity between cities, enabling more frequent multi-sited consumption. At the micro-level, individual consumers – motivated by the desire for cost-effective, unique, and scarce urban amenities – engage in frequent multi-sited consumption by strategically leveraging these differentiated amenities across the region. This interplay between policy-driven infrastructure improvements, urban specialisation, and individual consumer behaviour leads to meso-level redistribution and transformation of urban amenities. Some GBA cities adapt and specialise to meet demand by offering amenities that attract cross-border visitors, which may challenge the existing urban hierarchy in this region. These multidimensional interactions create a dynamic system where urban landscapes and consumption patterns mutually reinforce each other, reshaping the evolving integration of the GBA.

Figure 1. Analytic framework of multi-sited consumption in the Greater Bay Area

Credit: the authors.

The Greater Bay Area, which replaces the earlier designation of Pearl River Delta and stands in the continuity of the “one country, two systems” framework, is part of a deliberate rebranding effort by the Chinese central government to reflect this area’s evolving strategic importance and align it with Mainland China’s geopolitical ambition. The new term, which explicitly incorporates Hong Kong and Macao, two subregions enjoying higher degrees of self-governance and policy latitudes, reflects a broader vision to transform the region into a globally competitive metropolitan cluster. The GBA development, officially introduced in 2015[2] and subsequently escalated to a national-level development priority, was further substantiated into an outline plan in 2019[3] aimed at promoting China’s influence in the Asia-Pacific region.

The region historically shares a cultural heritage that predates its current administrative divisions. However, it was gradually fragmented by the imposition of three distinct administrations – British in Hong Kong, Portuguese in Macao, and Chinese in Guangdong. While these divisions were further entrenched by colonial policies and the establishment of physical borders, cross-border interactions persisted through regime changes (Berger and Lester 1997), contributing to maintain cultural and economic exchanges. Nonetheless, this context has also created socioeconomic, political, and cultural differences that participate in fuelling occasional tensions between Mainland Chinese and residents of the other two subregions. In particular, Hongkongers often perceive parallel trades, anchor babies, and unruly tourists as important issues, underscoring the complexities of multi-sited consumption in the Greater Bay Area.

Research methods and data analysis

Our study, conducted from July 2023 to March 2024, utilised both online and offline recruitment strategies. Using purposive and snowball sampling methods, we recruited 19 participants (Table 1) who either own multiple residences or frequently visit various cities in the GBA. We conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews to gain detailed insights into their consumer behaviours, preferences, and the challenges they face. While we recognise that the small sample size may limit the generalisability of our findings, and that a larger sample would provide a broader perspective on consumption dynamics across the region, we believe that our current sample is sufficiently robust to reveal nuanced patterns and offers valuable insights into multi-sited consumer behaviours in the GBA.

Table 1. Biographic information of interviewees[4]

| Name | Gender | Birth year | Occupation | Frequently visited cities |

| Xiaoke | Male | 1998 | Architectural engineer | Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Macao |

| Wenhao | Male | 2000 | Architectural engineer | Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Macao |

| Xinxin | Female | 1998 | Athletic coach | Zhuhai, Guangzhou, Macao, Shenzhen, Hong Kong |

| Leung Che | Male | 1988 | Car dealer | Zhuhai, Hong Kong, Macao |

| Xiaoling | Female | 1997 | Architectural engineer | Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Guangzhou |

| Bayi | Male | 1983 | Engineering project manager | Zhuhai, Hong Kong |

| Kee Li | Male | 1975 | Real estate agent | Macao, Zhuhai, Hong Kong |

| Lusu | Female | 1998 | Teacher | Zhuhai, Macao, Guangzhou |

| Kwan Ying | Female | 1994 | Freelancer | Zhuhai, Macao, Guangzhou |

| Woo Kar | Male | 1968 | Building materials supplier | Zhuhai, Macao, Guangzhou, Shenzhen |

| Lingjie | Female | 1976 | Immigration consultant | Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Guangzhou |

| Ziqing | Female | 1997 | Telecom account manager | Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Foshan |

| Manman | Female | 1993 | Insurance agent | Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Guangzhou |

| Baode | Male | 1993 | Semiconductor engineer | Hong Kong, Shenzhen |

| Taozi | Female | 1986 | Fund manager | Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Zhuhai |

| Wanhai | Male | 1994 | Insurance agent | Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Guangzhou |

| Weiwei | Female | 1997 | Real estate agent | Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Shenzhen |

| Xiaopen | Female | 2004 | Student | Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Guangzhou |

| Ate | Male | 2004 | Student | Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Macao |

Source: the authors.

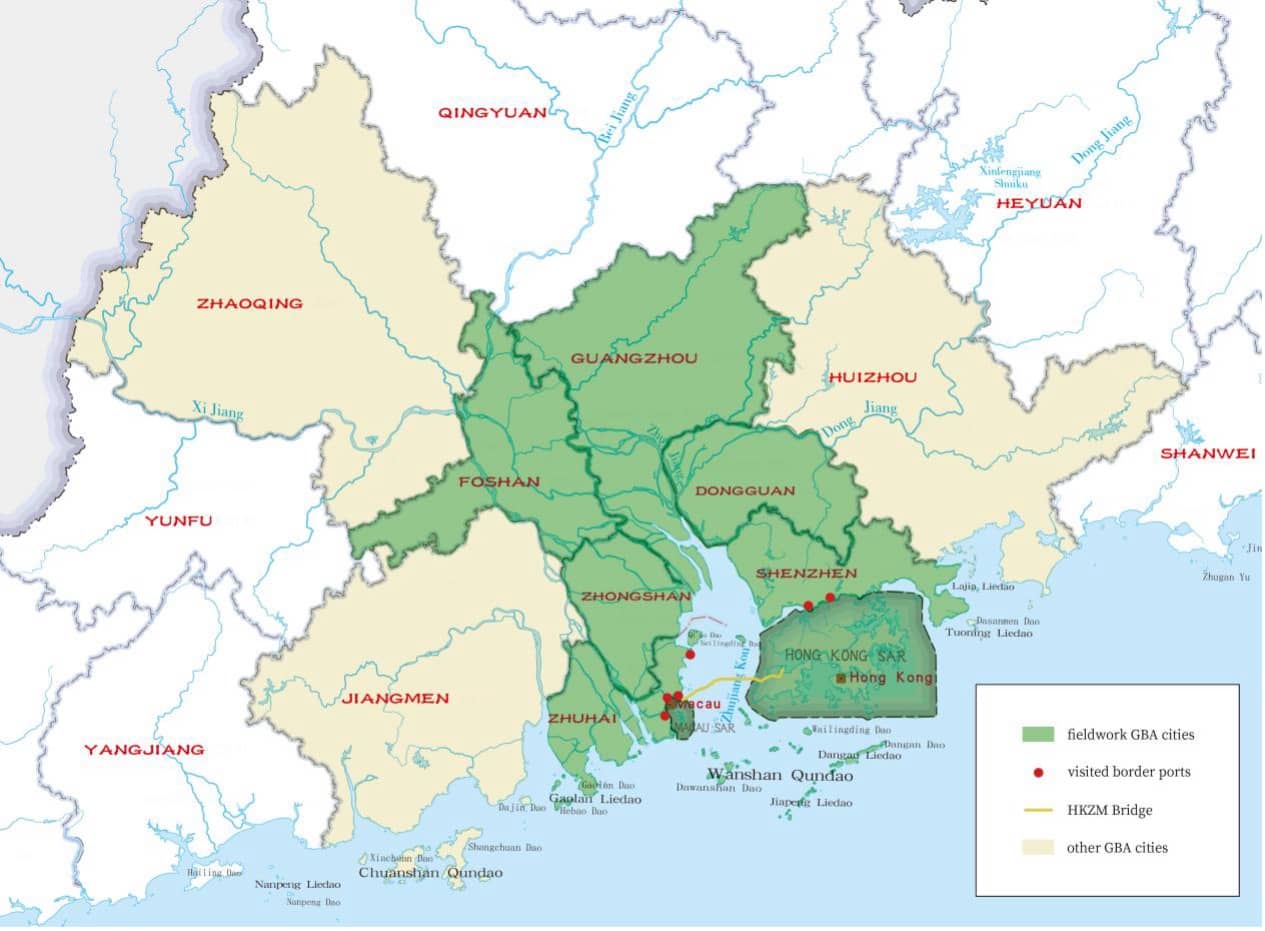

Furthermore, we performed on-site investigations at key sites such as the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge (hereafter, the “HKZM Bridge”), Gongbei Port (Zhuhai-Macao), Qingmao Port (Zhuhai-Macao), Hengqin Port (Zhuhai), Jiuzhou Port (Zhuhai), Futian Port (Shenzhen-Hong Kong), and Luohu Port (Shenzhen-Hong Kong). During these visits, we held discussion sessions with border inspectors working at the HKZM Bridge, Gongbei Port, Qingmao Port, Hengqin Port, and Jiuzhou Port on the Mainland side of the borders, as well as itinerant fishermen in Zhuhai, to gain first-hand insights into cross-border consumption practices. To enrich our findings, we engaged in participant observation by frequently travelling between Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Hong Kong, and Macao, as well as other GBA cities such as Foshan, Zhongshan, and Dongguan. These trips allowed us to undergo and observe border-crossing processes, population flows, and consumption activities at various commercial venues.

Finally, to complement our interview data, we collected a comprehensive range of archival documents, including reports on economic indicators, industrial policies, news articles, and other government newsletters. We also utilised 小紅書 (Xiaohongshu, literally “little red book,” also known as REDnote), a popular lifestyle app in China, to gather information on urban amenities that impact multi-sited consumption in the GBA, and valuable views on the subjective experiences and everyday practices of crossers. Together, these methods provided a holistic view of the factors influencing multi-sited consumption, the role of urban amenities in shaping such consumer behaviour, and consumer impacts on urban cluster amenities.

Figure 2. The fieldwork map of this study

Credit: created by the authors.

The interview and observation data were systematically analysed through a multi-step coding process. We first began with open coding to identify key themes within the interview transcripts and field observation notes. Building on these initial codes, we applied axial coding to group related themes into broader, interconnected categories. For example, we categorised “work and living conditions” and “primary reasons for cross-border activities” under the theme of “daily life,” while “expression of social identity” and “demand for unique products” were grouped into the “multi-sited consumption mechanisms” category. This process ultimately led to the development of four major thematic categories: daily life, multi-sited consumption mechanisms, significance of multi-sited consumption, and indicators of social change. To ensure the reliability and validity of our findings, we triangulated insights across multiple data sources, including observations, interviews, and archival documents. This methodological framework allowed us to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the factors driving multi-sited consumption and the ways individuals navigate and shape their daily lives across different urban contexts in the GBA.

Findings

This research examines the interplay between institutional renovations, urban amenities, and multi-sited consumer behaviour within the Greater Bay Area. At the macro-level, we analyse institutional supports that promote the development of urban cluster amenities. At the micro-level, we focus on the mechanisms that drive amenity-oriented, multi-sited consumption among individuals. At the meso-level, we examine how such consumption reshapes the redistribution and specialisation of urban amenities within the Greater Bay Area, which further influences the structural evolution of the GBA urban cluster.

The macro-level institutional building of GBA urban cluster amenities

Significant investments in physical infrastructure and policy initiatives at all government levels have played a transformative role in reshaping the GBA. These measures have both facilitated the redistribution of amenities and promoted specialisation at the meso-level, enabling each city to cultivate unique resources and services that contribute to an integrated urban cluster and a cohesive network of amenities across the cities. This coordinated development also influences individual consumption experiences by providing multi-sited consumption and making a wider range of specialised services and amenities more accessible and seamless.

The development of a systematic, multidimensional transportation network and streamlined customs procedures has been pivotal in fostering urban cluster amenities within the GBA. The transportation network integrates multiple transit modes – bridges, highways, railways, and maritime routes – catering to the diverse travel schedules and spatial preferences of residents and businesses. Key infrastructure connections, such as the Humen Bridge (opened in 1997), the HKZM Bridge (opened in 2018), and the Shenzhen-Zhongshan Corridor (opened in 2024), connect the four major development zones. Customs facilitation has also made notable progress. In the past, Hong Kong and Macao residents had to use vehicles with special “Yue Z” (粵Z, abbreviation for Guangdong Province) license plates to drive private cars into Guangdong Province, and obtaining these plates required meeting stringent investment and tax criteria. However, with the introduction of the “Northbound Travel for Macao Vehicles” policy in December 2022 and the “Northbound Travel for Hong Kong Vehicles” policy in July 2023, single-plate vehicles from Hong Kong and Macao became eligible to apply for entry permits into Guangdong. Starting 1 December 2024, Shenzhen residents, including permanent residents and those holding residence permits, can apply for multi-entry permits to Hong Kong. These permits allow unlimited visits within a year, with each stay capped at seven days. Similar policies for Macao will be available to Zhuhai residents from 1 January 2025. These policies have greatly enhanced cross-border mobility.[5] Moreover, the gradual implementation of the joint boundary clearance (hezuo chayan, yici fangxing 合作查驗, 一次放行) model at border crossings has streamlined clearance processes, particularly during peak hours. An official at the Hengqin Port between Macao and Zhuhai explained their efforts:

The designed clearance capacity is 220,000 people, with 10,000 to 16,000 vehicles. (…) The characteristic is “one clearance.”[6] (…) At Hengqin Port, Zhuhai and Macao authorities will inspect vehicles on the same lane and complete all procedures jointly. (…) Data collected by (…) one side is transmitted to the other. (…) We offer greater convenience to travellers. (Interview with Xuzhu, male, 13 July 2023)

Enhanced connectivity has enabled the specialisation and strategic redistribution of urban amenities across the region. Hong Kong and Macao are internationally recognised for offering highly globalised shopping experiences. In contrast, Guangzhou and Shenzhen serve as prominent consumption hubs in Mainland China, although the prevalence of global brands in these cities is deemed comparatively lower than in Hong Kong and Macao. Meanwhile, second-tier GBA cities such as Zhuhai, Foshan, and Dongguan are actively positioning themselves as regional consumption centres, contributing to a stratified and complementary network of urban amenities.[7] This hierarchical structuring of amenities lays a robust foundation for multi-sited consumption across the region. Various policy measures have further supported these practices. This is the case for payment systems for example.[8] Since July 2016, highlighted by the joint settlement of Guangdong-Hong Kong e-checks, integrated payment systems have enhanced cross-border consumption efficiency. Governments in Hong Kong, Macao, Shenzhen, and Zhuhai have introduced numerous initiatives to promote cross-border residence and consumption.

In addition to hierarchical specialisation of urban amenities across the region, each city, especially Mainland cities, develops unique amenities to meet diverse consumption needs, such as cost-effective housing, dining, and retail options. For instance, Zhuhai capitalises on its lower prices and seamless connectivity to Hong Kong and Macao via the HKZM Bridge to attract consumers from these regions to its automotive services, hotels, and dining establishments. Likewise, cities such as Guangzhou and Foshan leverage their cultural heritage, rooted in Cantonese and Lingnan traditions, and rebrand their cultural amenities for visitors. For example, from 19 to 28 July 2024, Guangzhou hosted the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Music and Food Festival. As urban amenities continue to evolve and consumer spending becomes a main driver of economic growth, both governments and businesses leverage diverse online and offline channels to highlight their competitive advantages, in order to position some amenities as specific and essential in this urban cluster. This increasing specialisation is reflected in perceptions shared by stakeholders.

The advancements in intra-regional transportation and customs have spurred a surge in amenity-driven, multi-sited consumption across the GBA. Zhuhai resident Xinxin describes how the ease of travel allows residents to enjoy a wide and accessible range of amenities across the region:

Since the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge opened, it is possible to make a day trip from Zhuhai to Hong Kong. In the GBA, you don’t need much planning; you can just go whenever you feel like and decide what to do once you’re there. (Interview with Xinxin, female, 17 December 2023)

Field observations during our research revealed how Shenzhen shopping malls and subway stations prominently display signage catering to Hong Kong visitors, including instructions in traditional Chinese characters for cross-border electronic wallets.[9] Although cross-border coordination remains challenging, these regional policies, combined with the diverse consumer needs of the GBA’s population, have highlighted the region’s function as a dynamic consumption hub.

The multi-sited consumption of micro-level individuals in the Greater Bay Area

The development of urban cluster amenities and the increasing specialisation of urban services have led to a rapid rise in multi-sited consumption in the GBA. After regular border crossings resumed in February 2023, Mainland cities have seen a significant influx of consumption originating from Hong Kong and Macao. Increasing cross-border consumption, especially northbound consumption by Hong Kong and Macao residents, has often made headlines. In 2023, Gongbei Port reported a cumulative total of over 100 million entries and exits, maintaining its status as the busiest land port in China for the eleventh consecutive year.[10] By October 2024, data from the HKZM Bridge customs indicated that average daily inbound and outbound traffic volume at the HKZM Bridge Port is about 16,200 vehicles, and the maximum single-day traffic volume has exceeded 22,800 vehicles.[11] Besides increased connectivity in the GBA, more micro-level factors drive cross-border mobility leading to multi-sited consumption. This study identifies three mechanisms behind this newly emerging consumer behaviour.

Multi-sited consumption of cost-effective amenities

Consumers who engage in cost-effective, multi-sited consumption primarily attempt to maximise the functional value of high-quality amenities by accessing them in locations where they are available at lower prices. This behaviour is influenced by significant cost-of-living disparities among the three subregions. For example, the price of an identical meal at the same chain restaurant can vary by two to three times between Hong Kong, Macao, and Shenzhen, as shown below in Table 2.

Table 2. Per capita spending at the same chain restaurant in different cities (RMB)

|

Hong Kong | Macao | Shen zhen | Zhu hai | Guang zhou | Zhong shan | Dong guan | Fo shan | ||||

| Sichuan cuisine | 135-204 | 182-198 | 68-91 | 69-85 | 68-84 | 60-77 | 59-79 | 59-75 | ||||

| Hot pot | 160-250 | 224-229 | 85-116 | 95-118 | 87-119 | 87-100 | 93-110 | 88-108 | ||||

| Snacks and fast food | 49-71 | 48 | 17-41 | 14-29 | 15-30 | 16-30 | 17-32 | 15-28 |

Source: the authors, with data retrived from Dazhong dianping 大眾點評, a trusted platform for restaurant reviews and ratings (accessed on 18 December 2024).

Such disparities create fertile ground for geographical arbitrage, where consumers capitalise on price differences across borders (Chan and Ngan 2018) when Hongkongers can visit Shenzhen in 14 minutes by high-speed rail. Consequently, our study finds that even high-income Hongkongers engage in cross-border trips for value-driven consumption, as budget pressures for essential items such as clothing, food, and housing increase significantly. Taozi, a Shanghai native who has worked in Hong Kong for over a decade, frequently travels to cities like Shenzhen and Zhuhai, and more distant ones such as Foshan, every one to two weeks for more affordable beauty services and children’s amusement parks. Prior to 2023, Taozi had never visited the cities in Guangdong Province for consumption purposes. She told us:

The key difference between Hong Kong and the Mainland is that Hong Kong requires higher minimum spending. For instance, children’s playgrounds in Hong Kong are smaller and more expensive, HKD 120 for just 50 minutes, compared to RMB 200 for an entire day in Shenzhen. Approximately 50% of expenses in Hong Kong cover rent. Similarly, beauty and nail services are far more cost-effective on the Mainland. The same services would cost twice as much in Hong Kong, accompanied by worse environments and hygiene standards. (Interview with Taozi, female, 11 March 2023)

Short video platforms such as Douyin 抖音 (the Mainland China and Hong Kong version of TikTok) and WeChat play a pivotal role in driving this trend by showcasing lifestyle experiences in Hongkong, Macao, and Mainland cities.

Another form of cross-border, multi-sited consumption can be conceptualised as cross-border residential bifurcation, where households strategically split their living arrangements to maximise economic and social benefits. In this arrangement, one spouse works in Hong Kong or Macao to earn higher income, while the other resides in a Mainland city with the children to benefit from more affordable housing, education, and daily living expenses. It is estimated that up to 100,000 cross-border families live in such a state of separation (Leung, Waters, and Ki 2021). This strategy reflects a deliberate optimisation of resources across borders, blending the economic opportunities of globalised urban hubs with the cost-effectiveness and family-oriented amenities of Mainland cities. Such arrangements underlie the complex interplay between economic pragmatism and lifestyle preferences in cross-border urban clusters.

Bayi, who graduated in Mainland China before working in Macao for ten years and subsequently spending six months in Hong Kong, serves as an exemplary case of this arrangement. He is currently employed as a senior project manager in Hong Kong, earning an annual salary of HKD 1 million, while his family resides in Zhuhai:

Living in Hong Kong, where spaces are so cramped and overcrowded, and food is so expensive, there’s hardly any sense of well-being. For me, trips between Hong Kong and Zhuhai are a form of relaxation: I earn money there and come back to my wife and son. (…) Considering the significance, it’s not a bother at all, right? (Interview with Bayi, male, 23 December 2023)

Multi-sited consumption of unique amenities

The GBA has developed a diverse array of unique amenities. Hong Kong offers international financial services and iconic street scenes from TV dramas. Macao is known for its gaming industry, Portuguese cuisine, and Portuguese-style architecture. Guangzhou and Foshan showcase elements of Lingnan and Cantonese cultures, cuisine, and architecture. Easy access to unique amenities reduces the time and effort required for multi-sited consumption, significantly enhancing the hedonic experience of consumers, as Xinxin, a fitness tutor who lives in Zhuhai explained in detail:

I have been making frequent trips to Hong Kong and Macao, typically once a month. My visits are mostly about enjoying the local cuisine and drinks, experiencing the vibrant and fresh atmosphere... Ultimately, these journeys are an opportunity for me to recharge and pay attention to myself. (Interview with Xinxin, female, 17 December 2023)

Distinctive amenities are often not products of government planning but rather the outcomes of decades or even centuries of heritage and historical development. The specialties of different areas make it difficult for any single city to encapsulate the full spectrum of unique amenities, compelling customers to travel to multiple places – or at least beyond their home cities – to fully experience them. In the past, the lack of promotion of amenities, transportation infrastructure, and streamlined border management posed significant challenges to this kind of multi-sited consumption. However, with advancements in transportation and the easing of cross-border restrictions, accessing these scattered cultural amenities has become more feasible. The consumption of unique amenities serves hedonic values. Lusu, a student who commutes daily between Zhuhai and Macao to save on living costs, takes a gruelling three-hour cross-border journey every day. To alleviate the stress of her routine, she seeks solace in the unique amenities of Guangzhou:

I go out and move around to make me feel better. (...) I visit Guangzhou every couple of weeks. I visit exhibitions, explore the old Lingnan buildings, and enjoy dessert soup (tangshui 糖水), which greatly relieves the psychological stress I experience. I think these trips are really important. (Interview with Lusu, female, 16 December 2023)

Multi-sited consumption of scarce amenities

The uneven distribution of scarce amenities naturally drives cross-border, multi-sited consumption, when individuals seek to optimise their access to high-quality goods and services that are limited in availability or constrained by geographical or regulatory factors in their home locations. In the Greater Bay Area, the rising demand for scarce amenities is primarily fuelled by an internationalised consumer environment in Hong Kong and Macao, creating a dynamic ecosystem where the GBA’s interconnected urban landscapes thrive on multi-sited consumption patterns.

A prime example of consuming scarce amenities is shopping at high-end luxury stores that offer highly exclusive items – products not only limited in quantity but often unavailable in other markets. The pursuit of luxury goods, such as designer clothing, rare watches, and exclusive jewellery, underlies the social value and prestige tied to owning such items, reinforcing owners’ social identity and social hierarchies. This type of consumption is particularly prominent in highly internationalised and developed urban centres such as Hong Kong and Macao, where these goods are readily accessible and often considered more trustworthy. One Macao resident who commutes daily to Zhuhai for work, visits clients in Hong Kong monthly, and earns an annual income exceeding RMB one million, remarked:

I consider myself part of the middle class and need to meet with clients. I usually wear shoes from luxury brands that cost around RMB 8,000. I am worried about purchasing fake products on the Mainland. I also have a penchant for watches, which I usually buy in Macao, or in Hong Kong if they’re unavailable in Macao. (Interview with Kee Li, male, 17 December 2023)

Moreover, such multi-sited consumption also extends to amenities with scarce functional advantages, offering specialised services and features that cater to specific needs across different locations. For example, as an international financial hub and the world’s largest offshore RMB business centre, Hong Kong offers scarce financial services unavailable in other GBA cities, including multi-currency banking, access to global financial markets, offshore RMB transactions, international insurance products, wealth management, and a free flow of capital, all supported by its low-tax regime and role as a global financial hub. Following the border reopening on 6 February 2023, demand for insurance from Mainland customers surged. In 2023, new business premiums from Mainland visitors reached approximately HKD 59 billion, representing a 27-fold increase compared to the previous year.[12] In addition to comprehensive international coverage and diverse investment options, insurance in Hong Kong also confers social prestige, showing financial sophistication and global awareness.

Reconfiguring meso-level urban amenities in the Greater Bay Area: The role of multi-sited consumption in recent transformation

The hierarchical structuring of amenities in the Greater Bay Area is not static but evolves through the dynamic interplay of national strategies, local policies, and grassroots multi-sited consumption patterns. While existing studies predominantly focus on the roles of national strategies and local policies, our research highlights how consumer behaviours actively reshape the GBA’s urban cluster amenities. In response to the broader economic downturn in Hong Kong, Macao, and Mainland China, the ebb and flow of three types of multi-sited consumption have driven the reconfiguration of GBA’s urban cluster amenities.

The decline and downgrade of urban amenities in Hong Kong and Macao

Hong Kong and Macao, long celebrated for their unique and scarce amenities, are facing growing pressure as locals increasingly travel north to Mainland cities such as Shenzhen and Zhuhai for more cost-effective alternatives. Hong Kong’s restaurant sector, for example, has been particularly hard hit, with many residents choosing to dine in Shenzhen or even farther north.[13] During the second quarter of 2023, Hong Kong residents spent approximately RMB 720 million dining in Shenzhen, which surpassed Hong Kong’s daily restaurant revenue during the same period. This shift toward cost-effective consumption has lowered the profitability and led to the closure of many restaurants in Hong Kong and Macao. An interviewee who moved from Jieyang City, Guangdong Province, to Macao 20 years ago have observed this change:

Several friends are running big restaurants in Macao, but their businesses are struggling. They’ve had to lay off chefs and servers and use robots to deliver dishes. (Interview with Woo Kar, male, 23 December 2023)

Moreover, scarce amenities of Hong Kong and Macao are no longer as scarce as they once were. For instance, Hong Kong’s financial services, particularly its insurance services, are becoming more accessible across the Greater Bay Area. In response to strong demand from Mainland clients, insurance service centres are set to open in Nansha (Guangzhou), Qianhai (Shenzhen), and Hengqin (Zhuhai), offering Hong Kong insurance services to Mainland consumers more directly. Consequently, the direct and indirect economic activities traditionally tied to cross-border activities may decline, posing challenges to Hong Kong’s economic ecosystem. Hong Kong, previously a preferred destination for Mainland consumers, has experienced a decline in Mainland visitors’ shopping spending from 2015 to 2023.

Figure 3. Mainland China visitors spending on shopping in million HKD (2015-2023)

Source: Tourism Expenditure Associated to Inbound Tourism (published quarterly), PartnerNet (香港旅業網), https://partnernet.hktb.com/en/research_statistics/research_publications/index.html?id=4110 (accessed on 17 December 2024).

These trends are also evident in the data about per capita spending by Guangdong visitors in Macao, a pattern observed consistently from 2015 to 2023 (see Figure 4). The statistical data reveals a dynamic trend in shopping expenditures since the inception of the GBA initiative. Initially, as border restrictions gradually eased, crossers spending expanded significantly. However, this growth began to contract in 2018. During the period from 2020 to 2022, per capita consumption of shopping reached its peak, specifically in compras shopping. This surge can likely be attributed to stringent border policies that selectively favoured cross-border consumers with stronger consumption intentions and higher purchasing power. To compensate for the reduced frequency of travel, cross-border customers significantly increased their spending per trip. Moreover, some consumers adopted stockpiling strategies, further driving up the short-term average consumption levels. Following the resumption of normal border crossings in February 2023, there was a brief resurgence in consumer spending, but this was followed by another decline in the consumption of scarce amenities.

Figure 4. Per capita consumption in Macanese Pataca (MOP) of Guangdong visitors in Macao (2015-2023)[14]

Source: Macao Tourism Data plus, Visitor Expenditure Survey (https://dataplus.macaotourism.gov.mo/Publication/Other?lang=E, accessed on 17 December 2024).

We further conducted a quarterly comparison of the per capita consumption data (Figure 5). The results indicate a decline in the appeal of scarce amenities, including cosmetics, perfumes, jewellery, and watches, as well as unique amenities such as local food products, among crossers from Guangdong Province. Since the resumption of normal border crossings in February 2023, there has been a noticeable decline in the appeal of Macao’s scarce and unique amenities.

Figure 5. Per capita consumption in MOP of Guangdong visitors in Macao (2023-2024)

Source: Macao Tourism Data plus, Visitor Expenditure Survey

Source: Macao Tourism Data plus, Visitor Expenditure Survey

(https://dataplus.macaotourism.gov.mo/Publication/Other?lang=E, accessed on 17 December 2024).

The consumption of scarce amenities in Hong Kong and Macao, especially in the luxury sectors, has significantly declined and even been downgraded. The economic downturn has led to fewer consumers making substantial purchases. As a Macao interviewee observed:

It’s clear that while there are still plenty of people browsing luxury items in Hong Kong and Macao, there are significantly fewer buyers. I have friends in the business of selling top-tier luxury watches. They used to sell at least one a month, but now they say they might not sell even a single watch worth over a million in an entire month. (Interview with Kee Li, male, 17 January 2024)

Also, certain macro-level strategies, such as anti-corruption campaigns and anti-money laundering efforts, significantly affect whether and to what extent Mainland consumers utilise the amenities offered in Hong Kong and Macao. For instance, since 2014, the Central Government of the People’s Republic of China has intensified its efforts against money laundering. Policies have been introduced to restrict the use of UnionPay cards in Macao’s casinos, aiming to reduce illegal capital flows through gambling activities. Concurrently, Macao Government has also enhanced its regulation of the gaming industry, increased surveillance of suspicious transactions, and aligned its practices with international standards to prevent the exploitation of its financial system for illicit funds. Moreover, since 2013, intensified anti-corruption campaigns on the Mainland have significantly curtailed high-roller activity in Macao’s casinos, challenging gaming industry. This trend was further exacerbated by the Macao Government’s efforts starting from 2019 to diversify its economy away from gambling, aiming for broader economic transformation. Therefore, Macao’s gaming industry as unique amenities has also experienced a significant decline. The gross gaming revenue stood at MOP 15,255 million in 2023, which remains significantly below the figures of MOP 24,371 million in 2019 and MOP 19,237 million in 2015[15].

The growth and redistribution of urban amenities in the Mainland GBA

Mainland cities such as Shenzhen and Zhuhai have acted swiftly in response to the influx of cost-effective consumption by people from Hong Kong and Macao. Shenzhen has targeted Hong Kong and Macao residents and assisted them with using the newly developed iShenzhen app. This app features a dedicated section for Hong Kong and Macao services, offering multilingual support and providing streamlined access to essential services such as social security, housing funds, and medical appointments. Also, central business districts have introduced transportation subsidies, integrated payment systems, and discount activities. Likewise, Zhuhai also shows a strong commitment to attracting cross-border consumption by Hong Kong and Macao residents. Kee Li noted the concerted efforts of Zhuhai businesses:

Every industry, especially dining, is trying to attract us. I see on Douyin and WeChat videos that they target us explicitly, with titles like “What kind of roast chicken do Macao people like?” rather than “Where do Zhuhai people go for roast chicken?” (Interview with Kee Li, male, 23 December 2023)

Although the current GBA hierarchical structure of urban amenities remains intact, with Hong Kong and Macao still regarded as premium destinations for unique and scarce amenities, the rapid growth of Mainland cities such as Shenzhen and Zhuhai is beginning to challenge this balance. Shenzhen’s rapidly expanding economy, coupled with the increasing availability of various types of amenities, has already attracted significant consumption from Hong Kong residents such as dining and entertainment consumption. Similarly, Zhuhai’s strategic development and proximity to Macao make it an appealing alternative for cost-sensitive consumers. For example, restaurants near Gongbei Port offer discounted group deals that attract budget-conscious diners, while the region has also witnessed an influx of high-end consumption, such as real estate purchases, into both Zhuhai and neighbouring Zhongshan. As these Mainland cities continue to grow and diversify their offerings, they may gradually absorb more cross-border consumption, potentially redefining the hierarchical structure of amenities in the GBA. This shift could lead to a more decentralised and competitive urban cluster landscape, where Shenzhen and Zhuhai play increasingly dominant roles in shaping regional consumption patterns.

This ongoing shift is influenced by the interplay of macro-level strategies, such as the push for regional integration, and micro-level individual consumption behaviours in response to economic pressures, as consumers tend to seek cost-effective and accessible options beyond Hong Kong and Macao. These micro-level behaviours, when aggregated, begin to drive meso-level transformation in the distribution and specialisation of urban amenities, as Mainland cities are adapting to meet the evolving demands of cross-border consumers. Leung Che, a car dealer, who is a Hong Kong native and directly involved in facilitating the movement of Hong Kong vehicles to the Mainland, noted the potential impact of micro-level actions on meso-level urban amenities:

Why do Hong Kong car owners want to come to the Mainland now? It’s because they want to get their cars repaired. The cost in Hong Kong is three to four times that of Zhuhai. (...) This will impact Hong Kong, causing a downgrade in consumption for vehicle owners. This will result in reduced earnings for those involved in related businesses in Hong Kong, leading to decreased business activity and ultimately impacting the overall GDP. (Interview with Leung Che, male, 22 December 2023)

This trend highlights the dynamic and fluid nature of urban hierarchies in the GBA, where macro-level policies and grassroots consumption patterns converge to reshape the regional landscape.

Conclusion

This paper explores the dynamic interplay between macro-level policies, micro-level consumer behaviour, and meso-level transformation in shaping the Greater Bay Area’s urban landscape by introducing the concept of multi-sited consumption and urban cluster amenities, and leveraging qualitative interviews alongside secondary data. It contributes to the existing literature in three aspects.

First, this research provides a comprehensive analysis and advances our understanding of cross-border consumption by bridging macro-, meso-, and micro-level perspectives. It finds that macro-level efforts, such as regional economic integration, improved infrastructure, and streamlined border controls, facilitate multi-sited consumption by increasing cross-border mobilities. These institutional buildings lead GBA residents to increasingly participate in the consumption of amenities that are cost-effective, unique, or scarce.

Second, the article expands on the existing theories of urban cluster amenities and demonstrate how individual’s multi-sited consumption can reflect and further drive transformations in the spatial and functional hierarchies of interconnected cities. Rather than focusing on macro-level policies, this study emphasises the critical role of micro-level consumption in reshaping regional integration and urban transformation from a bottom-up perspective.

Third, the findings offer new insights into the implications of unevenly distributed amenities in cross-border regions, contributing to the literature on regional development. They reveal that the multi-sited consumption practices are leading to the redistribution and specialisation of urban amenities across the GBA and contributing to a reconfiguration of its urban hierarchy and regional landscape.

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the 2023 Winter Forum on Sociology of Consumption and the “Sociology of Consumption” session of the Annual Meeting of Chinese Sociology in 2024. We express our sincere gratitude for the valuable feedback in these meetings. We are also grateful to the editors from China Perspectives and anonymous reviewers, and to You Tianlong from Yunnan University who has made this special feature possible.

Manuscript received on 30 July 2024. Accepted on 7 December 2024.

References

ANDERSON, James, and Liam O’DOWD. 1999. “Borders, Border Regions and Territoriality: Contradictory Meanings, Changing Significance.” Regional Studies 33(7): 593-604.

ARNTZ, Melanie, Eva BRÜLL, and Cäcilia LIPOWSKI. 2023. “Do Preferences for Urban Amenities Differ by Skill?” Journal of Economic Geography 23(3): 541-76.

BALDWIN, Richard, and Charles WYPLOSZ. 2015. The Economics of European Integration. London: McGraw-Hill Education.

BAUDRILLARD, Jean. 1998. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. London: Sage Publications.

BECKERT, Jens. 2016. Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations and Capitalist Dynamics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

BERGER, Suzanne, and Richard K. LESTER (eds). 1997. Made by Hong Kong. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

BERGSTRESSER, Sara M. 2022. “Baby Milk and Boundary Transgressions at the Hong Kong-Mainland China Interface.” Anthropology News. https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/baby-milk-and-boundary-transgressions-at-the-hong-kong-mainland-china-interface/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

BERTINELLI, Luisito, and Duncan BLACK. 2004. “Urbanization and Growth.” Journal of Urban Economics 56(1): 80-96.

BOEHMER, Charles R., and Sergio PENA. 2012. “The Determinants of Open and Closed Borders.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 27(3): 273-85.

BOURDIEU, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

BURSTEIN, Ariel, Sarah LEIN, and Jonathan VOGEL. 2024. “Cross-border Shopping: Evidence and Welfare Implications for Switzerland.” Journal of International Economics 152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2024.104015

CAMPBELL, Colin. 1987. The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

CARLINO, Gerald A., and Albert SAIZ. 2019. “Beautiful City: Leisure Amenities and Urban Growth.” Journal of Regional Science 59(3): 369-408.

CHAN, Anita K. W., and Lucille L. S. NGAN. 2018. “Investigating the Differential Mobility Experiences of Chinese Cross-border Students.” Mobilities 13(1): 142-56.

CLARK, David, and Christopher MURPHY. 1996. “Countywide Employment and Population Growth: An Analysis of the 1980s.” Journal of Regional Science 36(2): 235-56.

CLARK, Terry Nichols, Richard LLOYD, Kenneth K. WONG, and Pushpam JAIN. 2003. “Amenities Drive Urban Growth: A New Paradigm and Policy Linkage.” In Terry Nichols CLARK (ed.), The City as an Entertainment Machine. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 291-322.

COLLINS, Francis L. 2012. “Transnational Mobilities and Urban Spatialities: Notes from the Asia-Pacific.” Progress in Human Geography 36(3): 316-35.

COSTA, Dora L., and Matthew E. KAHN. 2000. “Power Couples: Changes in the Locational Choice of the College Educated, 1940-1990.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(4): 1287-315.

FAIST, Thomas. 2013. “The Mobility Turn: A New Paradigm for the Social Sciences?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36(11): 1637-46.

FANG, Chuanglin, and Danlin YU. 2017. “Urban Agglomeration: An Evolving Concept of an Emerging Phenomenon.” Landscape and Urban Planning 162: 126-36.

FENG Yi, Chien-Chiang LEE, and Diyun PENG. 2023. “Does Regional Integration Improve Economic Resilience? Evidence from Urban Agglomerations in China.” Sustainable Cities and Society 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.104273

FLORIDA, Richard. 2019. The Rise of the Creative Class: Revisited. New York: Basic Books.

GRAELLS-GARRIDO, Eduardo, Feliu SERRA-BURRIEL, Francisco ROWE, Fernando M. CUCCHIETTI, and Patricio REYES. 2021. “A City of Cities: Measuring How 15-minutes Urban Accessibility Shapes Human Mobility in Barcelona.” Plos ONE 16(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250080

HAYES, Matthew. 2014. “‘We Gained a Lot Over What We Would Have Had’: The Geographic Arbitrage of North American Lifestyle Migrants to Cuenca, Ecuador.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40(12): 1953-71.

LEAL, Andrés, Julio LÓPEZ-LABORDA, and Fernando RODRIGO. 2010. “Cross-border Shopping: A Survey.” International Advances in Economic Research 16(2): 135-48.

LEUNG, Maggi W. H., Johanna L. WATERS, and Yutin KI. 2021. “Schools as Spaces for In/exclusion of Young Mainland Chinese Students and Families in Hong Kong.” Comparative Migration Studies 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-021-00269-7

MARTIN, Ron, and Peter SUNLEY. 2015. “On the Notion of Regional Economic Resilience: Conceptualization and Explanation.” Journal of Economic Geography 15(1): 1-42.

NEWMAN, Michael. 2020. “Rethinking Borders.” In Wendy STEELE, Tooran ALIZADEH, Leila ESLAMI-ANDARGOLI, and Silvia SERRAO-NEUMANN (eds.), Planning Across Borders in a Climate of Change. London: Routledge. 15-30.

NSHIMBI, Christopher Changwe. 2019. “Life in the Fringes: Economic and Sociocultural Practices in the Zambia-Malawi-Mozambique Borderlands in Comparative Perspective.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 34(1): 47-70.

PAASI, Anssi, Eeva-Kaisa PROKKOLA, Jarkko SAARINEN, and Kaj ZIMMERBAUER (eds.). 2018. Borderless Worlds for Whom? Ethics, Moralities and Mobilities. London: Routledge.

PINE, B. Joseph, and James H. GILMORE. 1999. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

RECKWITZ, Andreas. 2020. Society of Singularities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

SCOTT, Allen J. 2001. Global City-regions: Trends, Theory, Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

——. 2008. Social Economy of the Metropolis: Cognitive-cultural Capitalism and the Global Resurgence of Cities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

SHI, Chenchen, Xiaoping ZHU, Haowei WU, and Zhihui LI. 2022. “Urbanization Impact on Regional Sustainable Development: Through the Lens of Urban-rural Resilience.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215407

SU, Yaqin, Yue HUA, and Xiaobo LIANG. 2019. “Toward Job or Amenity?: Evaluating the Locational Choice of Internal Migrants in China.” International Regional Science Review 42(5-6): 400-30.

SZYTNIEWSKI, Bianca, and Bas SPIERINGS. 2014. “Encounters with Otherness: Implications of (Un)familiarity for Daily Life in Borderlands.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 29(3): 339-51.

TAN, Chiew Hui, and Simone CHUNG. 2023. “Malaysia-Singapore Geopolitics Spatialised: The Causeway as a Palimpsest.” In Quazi Mahtab ZAMAN, and Greg G. HALL (eds.), Border Urbanism: Transdisciplinary Perspectives. Cham: Springer.

TAN, Jiajie, and Yinging LI. 2024. “Influence of the Perceptions of Amenities on Consumer Emotions in Urban Consumption Spaces.” PLoS ONE 19(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304203

URRY, John. 2007. Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

VILLANEUVA, Jose L. Wong, Tetsuo KIDOKORO, and Fumihiko SETA. 2020. “Cross-border Integration, Cooperation, and Governance: A Systems Approach for Evaluating ‘Good’ Governance in Cross-border Regions.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 37(5): 1047-70.

VORLEY, Tim. 2008. “The Geographic Cluster: A Historical Review.” Geography Compass 2(3): 790-813.

WANG, Lu, and Lucia LO. 2007. “Immigrant Grocery-shopping Behavior: Ethnic Identity versus Accessibility.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 39(3): 684-99.

WANG, Ning 王寧. 2014. “地方消費主義, 城市舒適物與產業結構優化: 從消費社會學視角看產業轉型升級” (Difang xiaofei zhuyi, chengshi shushiwu yu chanye jiegou youhua: Cong xiaofei shehuixue shijiao kan chanye zhuanxing shengji, Local consumerism, urban amenities and the optimisation of industrial structure: Industrial upgrading seen from the perspective of the sociology of consumption). Shehuixue yanjiu (社會學研究) 29(4): 24-48.

XIANG, Biao, and Johan LINDQUIST. 2014. “Migration Infrastructure.” International Migration Review 48(1): 122-48.

YAN, Xiang, Shan LU, Shenjing HE, and Jiekui ZHANG. 2022. “Cross-city Patient Mobility and Healthcare Equity and Efficiency: Evidence from Hefei, China.” Travel Behaviour and Society 28: 1-12.

ZUKIN, Sharon. 2010. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[1] Erin Hale, “In Pricey Hong Kong, Residents Flock to China for Cheaper Dining, Shopping,” Al Jazeera, 27 May 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2024/5/27/in-pricey-hong-kong-residents-flock-to-china-for-cheaper-dining-shopping (accessed on 5 December 2024).

[2] National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China 國家發展改革委, 外交部, 商務部, “推動共建絲綢之路經濟帶和21世紀海上絲綢之路的願景與行動” (Tuidong gongjian sichou zhi lu jingjidai he 21 shiji haishang sichou zhi lu de yuanjing yu xingdong, Vision and Action on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Twenty-first Century Maritime Silk Road), 28 March 2015, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/wjb_673085/zzjg_673183/gjjjs_674249/gjzzyhygk_674253/ydylfh_692140/zywj_692152/201503/t20150328_10410165.shtml (accessed on 17 December 2024).

[3] Central Committee of the Communist Party, State Council 中共中央, 國務院, “粵港澳大灣區發展規劃綱要” (Yuegang’ao dawanqu fazhan guihua gangyao, Outline Development Plan for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area), 18 February 2019, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202203/content_3635372.htm#1 (accessed on 17 December 2024).

[4] All names used in this article are pseudonyms.

[5] National Immigration Administration 中華人民共和國出入境管理局, “關於在廣東省深圳市, 珠海市和橫琴粵澳深度合作區實施赴香港,澳門旅遊‘一簽多行’‘一週一行’政策的公告”(Guanyu zai Guangdong sheng Shenzhen shi, Zhuhai shi he Hengqin Yue Ao shendu hezuoqu shishi fu Xianggang, Aomen lüyou “yi qian duo xing” “yi zhou yi xing” zhengce de gonggao, Announcement on Implementing the “Multiple-entry Permits” and “One Trip per Week” Policies for Travel to Hong Kong and Macao in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and the Guangdong-Macao In-Depth Cooperation Zone in Hengqin), 29 November 2024, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202411/content_6990072.htm (accessed on 30 November 2024).

[6] Traditionally, crossers between Zhuhai and Macao or between Hong Kong and Shenzhen had to pass through two checkpoints, queuing and undergoing verification twice. By integrating inspections from both Zhuhai and Macao authorities into a single process, this system allows travellers and goods to clear customs with a single inspection.

[7] People’s Government of Guangdong Province 廣東省人民政府, “廣東省人民政府辦公廳關於印發廣東省進一步提振和擴大消費若干措施的通知” (Guangdong sheng renmin zhengfu bangongting guanyu yinfa Guangdong sheng jin yibu tizhen he kuoda xiaofei ruogan cuoshi de tongzhi, Notice of the General Office of the People’s Government of Guangdong Province on Issuing Several Measures to Further Boost and Expand Consumption in Guangdong Province), 24 November 2023, https://www.gd.gov.cn/zwgk/wjk/qbwj/ybh/content/post_4289277.html (accessed on 25 April 2024).

[8] As the GBA operates under the “one region, two systems” principle and three currencies, streamlining cross-border payments has been a key focus for regional cooperation.

[9] The Hong Kong WeChat Pay e-wallet, in collaboration with China UnionPay, has launched a two-way cross-border mobile payment service. This service enables Hong Kong users to make QR code payments and app-based payments using their WeChat Pay (Hong Kong) wallet both in Hong Kong and on the Mainland. Additionally, mainland tourists visiting Hong Kong and Macao can also use cross-border electronic wallets for payments in a similar way.

[10] “拱北口岸又‘破億’連續11年成為全國客流最大陸路口岸” (Gongbei kou’an you “po yi” lianxu 11 nian chengwei quanguo keliu zuida lulu kou'an, Gongbei Port has surpassed 100 million passengers again, becoming the country’s largest land port for passenger traffic for 11 consecutive years), Hizh.cn (珠海網), 31 December 2023, https://pub-zhtb.hizh.cn/a/202312/31/AP65912748e4b0f9e3e8eb80e2.html (accessed on 14 October 2024).

[11] “透過數據看‘流動’活力: 港珠澳大橋累計驗放車輛超1270萬輛次” (Touguo shuju kan “liudong” huoli: Gangzhu’ao daqiao leiji yanfang cheliang chao 1270 wan liangci, Looking at the vitality of “mobility” through data: Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge has inspected and released more than 12.7 million vehicles) CCTV.com (央視網), 22 October 2023, https://news.cctv.com/2024/10/22/ARTIs7R9dl5geC4DQ9pXJDh4241022.shtml (accessed on 22 October 2024).

[12] “香港保監局: 2023年內地訪客新造業務保費約590億港元, 為需求釋放而非大規模走資” (Xianggang baojianju: 2023 nian neidi fangke xin zao yewu baofei yue 590 yi Gangyuan, wei xuqiu shifang er fei da guimo zouzi, Hong Kong insurance authority: In 2023, new business premiums from Mainland visitors reached approximately HKD 59 billion, driven by demand release rather than large-scale capital outflows), Investing.com (英為財情), 20 January 2024, https://cn.investing.com/news/stock-market-news/article-2308235 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

[13] Hung Faan Yu 孔繁栩, “2023年7192萬港人人次出境. 北上逾半億. 南下內地客人次僅及一半”(2023 nian 7192 wan Gangren renci chujing. Beishang yu ban yi. Nanxia neidi ke ren ci jin ji yi ban, In 2023, 71.92 million person-trips of Hong Kong residents traveled outbound. Over 50 million trips heading north to the Mainland, while the number of trips by visitors from the Mainland travelling south to Hong Kong was only about half of that), hk01.com (香港01), 31 December 2023, https://www.hk01.com/article/976477?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral (accessed on 14 October 2024)

[14] Given that data is available for only three quarters in 2020 and 2024, this table excludes data from these two years to maintain consistency and accuracy.

[15] Government of Macao Special Administrative Region Statistics and Census Service 澳門特別行政區政府統計暨普查局, “幸運博彩毛收入” (Xingyun bocai mao shouru, Gross revenue from games of chance), https://www.dsec.gov.mo/ts/#!/step2/KeyIndicator/zh-CN/247 (accessed on 25 October 2024).