BOOK REVIEWS

The Making of Border Infrastructures: Evolution and Interaction with Cross-border Migration on the China–Myanmar Border

Tianlong You is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Sociology at Yunnan University, No. 2 Cuihu North Road, Wuhua District, Kunming, China (tyou0410@gmail.com).

Haijing Zhang is PhD student of the Department of Sociology at Shanghai University, No. 333 Nanchen Road, Baoshan District, Shanghai, China (zhjcarbon@shu.edu.cn).

Introduction

According to the eighth Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Survey (2021),[1] Yunnan, China’s southwestern province bordering Myanmar, Vietnam, and Laos, is now only second to Guangdong, the nation’s most economically prosperous province, as the primary destination for international migrants. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, Yunnan recorded 30 million cross-border entries, mainly by Myanmar and Vietnamese migrants. Despite this high volume of cross-border movement, China only recently developed a complex infrastructure, both institutional and physical, along its southwestern borders. For much of its history, China did not possess the economic capacity to invest in such infrastructure, leaving border areas underdeveloped and allowing local communities to maintain cross-border ethnic and familial connections with limited interference (Dean, Sarma, and Rippa 2024). However, since the early twenty-first century, Yunnan has seen the construction of substantial infrastructures, which have enabled the control of cross-border mobilities and materially transformed border society, particularly in response to growing security concerns such as the pandemic (Plümmer 2022; You and Romero 2022).

These developments result from three competing but coexisting institutional logics – security, market, and community – shaped by interactions and negotiations among various actors. At China’s southwestern borders, where well-established migrant networks overlap with national security concerns, minimal infrastructure in the early decades of the People’s Republic, constrained by limited state capacity, fostered a self-reinforcing laissez-faire environment. Ordinary residents participated in cross-border migration, trade, and criminal activities, often underregulated by the state. During the early reform era, economic development became the central focus, prompting the construction of border infrastructures aimed at facilitating cross-border trade and exchanges. This market-driven logic prioritised the flow of goods, services, and people over security concerns. The third phase saw the alignment of the interests of profit-driven individuals, development-oriented local governments, and an economic-reformist central government. Infrastructure such as transport networks, customs facilities, and free trade zones stimulated migration and trade, and further embedded economic logic at the local level. However, growing geopolitical tensions and national security concerns eventually shifted the central government’s focus towards a security-centric approach, supported by increased state capacity after years of economic growth. This shift led to tighter border control and disrupted established migration networks and economic flows. In response, border residents adopted more sophisticated and costly migration strategies, generating unintended and unexpected consequences. The interplay among these three institutional logics sets the stage for increasingly divergent outcomes as each logic reinforces itself while disrupting the others. Together, they shape the governance and long-term development of border areas in complex ways.

Bringing together theories of migration infrastructure, institutional logic, and cumulative causation, this article develops an analytical framework to understand the development of border infrastructures along China’s southwestern borders. Drawing on extensive fieldwork conducted in Ruili, a major port city between China and Myanmar, as well as focus group-style interviews with local stakeholders, this study examines the interplay of logics behind the evolution of border infrastructures and their multifaceted impacts on border society. This framework contributes to existing knowledge by bridging macro-level institutional dynamics with micro-level social processes, offering a more comprehensive understanding of how border infrastructures shape, and are shaped by, migration flows, governance strategies, and local agency. It provides a lens to analyse borderlands as dynamic spaces of negotiation, emphasising their critical role in mediating global, national, and local interactions.

Cumulative causal effects of institutional changes on cross-border migration

Cumulative causation, the dominant theory used in the studies on the US-Mexico border by Massey and his colleagues, is a self-reinforcing process making migration increasingly likely over time, both at the individual and institutional levels (Massey et al. 1993). Once migration from a particular area begins, it tends to create conditions that make further migration more probable. Existing literature emphasises the critical role of migration networks in this process, as they reduce the risks and costs associated with future migrants by providing essential information, financial assistance, and support systems (Beine, Docquier, and Özden 2011). These networks help cultivate a culture of migration, where moving abroad becomes a socially accepted and often expected way to improve one’s socioeconomic status in the sending regions. Over time, the cumulative effects of these networks and cultural shifts can lead to sustained migration flows, perpetuating and expanding the migration process, and often making it difficult to reverse or control (Massey, Durand, and Malone 2002).

In what are now referred to as border societies, historical cross-border migration or trade activities often predate the establishment of nation-state boundaries and have long fostered social and economic ties between communities on either side of the border (Faist 2000). These early interactions lay the foundation for migration networks, shared cultural practices, and economic interdependencies that encourage further movement and exchange (Brettell and Hollifield 2015). As these ties deepen, the border increasingly becomes a crucial site of interactions, where cross-border activities become integral to everyday life (Konrad 2015). Over time, the cumulative effects of these interactions significantly transform the social and economic landscape of border regions (Anderson and O’Dowd 1999). Increased cross-border movement often simulates local economies, attracts investment, and enhances state capacity for more effective border governance (Massey et al. 1998). However, this cumulative process may also give rise to challenges, including increased competition for resources, heightened social tensions, and the entrenchment of informal economies that operate outside the reach of state regulation.

In addition to influencing individual behaviours, self-reinforcing migration also triggers institutional responses, including recruitment agencies, financial services, and specific migration policies that may facilitate or inhibit further migration (Czaika and de Haas 2014). Moreover, these institutional changes have cumulative effects by setting off a chain of events that progressively reinforces and amplifies the impact of the initial institutional change over time (Hanson 2009; Gibson and Mckenzie 2014). When an institution such as a government, legal system, or business organisation implements a policy shift or structural adjustment, it sets off a chain of effects. These changes create new opportunities, challenges, or incentives that influence the behaviour of individuals and other institutions within the system. In turn, these behaviours can prompt additional institutional responses, such as the creation of new regulations, shifts in public opinion, or further policy adjustments. This cycle often perpetuates itself, building on the initial policy change (Hollifield and Wong 2014). This cumulative effect illustrates how institutional changes, even if modest at the beginning, often lead to significant and long-lasting transformations in social structures, economic patterns, and migration dynamics (Mahoney and Thelen 2010).

The border as migration infrastructures with cumulative effects

Borders are not static demarcations between nation-states, but the combination of physical infrastructure, policies, and socioeconomic dynamics that continuously evolve to regulate movement, trade, and interactions across geographic and political boundaries. Infrastructure encompasses the fundamental physical and organisational structures that support the functioning of a society, economy, or system. These structures include a wide array of facilities, systems, and services, such as transport networks, power grids, and water supply, all of which are essential for daily life and economic activity (Suga, Tawada, and Yanase 2023; Bi 2024). Despite also having the potential to exacerbate inequality, displacement, and conflict in some circumstances, infrastructure provides a foundation for economic growth, social stability, and technological progress (Flyvbjerg 2014; Weijnen and Correljé 2021). Beyond its material facets, infrastructure encompasses the regulatory and institutional frameworks that govern its operation and maintenance, ensuring that it meets the needs of the population and adapts to changing circumstances (Star 1999). As a dynamic and evolving system, infrastructure reflects the priorities and values of the states it supports, playing a crucial role in shaping how communities are organised, how they interact with each other and the broader institutional context, and influencing many aspects of these interactions, in this research, for instance, by affecting migrants’ accessibility of education and healthcare facilities, facilitating or hindering their social integration, enabling or constraining cross-border trade, and shaping migration patterns in the border regions.

Migration infrastructure refers to the complex systems and networks that facilitate, regulate, and control the movement of people. These infrastructures encompass a wide array of elements, including legal frameworks, recruitment agencies, visa and passport systems, and customs enforcements, all of which work together to manage migration flows (Xiang and Lindquist 2014). Migration infrastructure is not just about the physical and technological means by which people move; it also includes the social, economic, and political institutions that shape the conditions and possibilities of migration (Anderson 2019). This infrastructure is crucial in shaping the experiences of migrants, influencing everything from the routes they take to the opportunities and challenges they face upon arrival. Also, migration infrastructure is deeply embedded in global and local power dynamics, often reflecting and reinforcing existing inequalities (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Sørensen 2017). By determining who can migrate, how they can migrate, and what their legal statuses are, migration infrastructures have a profound impact on the social, economic, and political outcomes of migration (De Genova 2023).

Contemporary borders, which consist of physical facilities and fortifications, legal and administrative mechanisms, technological and security systems, economic and trade functions, and cultural-symbolic dimensions, serve as spaces of governance, interaction, and contestation shaped by globalisation and security concerns, and can thus be conceptualised as infrastructures that not only demarcate territorial boundaries but also regulate the movement of people, goods, and information. Borders, as infrastructure, are assemblages of physical, legal, and technological components that work together to manage mobility and enforce state sovereignty (Mezzadra and Neilson 2013). They include an array of material and symbolic elements, including checkpoints, surveillance systems, customs regulations, and legal frameworks, all of which function to control access and flow across boundaries (Jones and Johnson 2016). Borders are therefore active, dynamic systems that shape social, economic, and political interactions. As such, they are deeply intertwined with broader processes of globalisation, security, and migration, serving as sites where global flows are negotiated and contested (Larkin 2013). As borders privilege certain forms of mobility while restricting others, from the infrastructural perspective, they structure inequalities by offering differential access to resource opportunities.

Like all infrastructures, border infrastructures are shaped by a diverse range of entities operating within a framework of multilevel governance (Bache and Flinders 2015; Gerlak and Mukhtarov 2016). This development typically involves central and local governments, which coordinate to establish policies and manage resources (Lavenex and Kunz 2020). However, the roles of various non-state actors, such as ordinary citizens, market institutions, and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), are also crucial. These actors contribute to the evolution of border infrastructure by providing social services, advocating for specific needs, or influencing policy through various means. Their differentiated approaches to shaping border infrastructure, although beneficial to each of them individually, inevitably lead to inherent tensions. Different actors operate under distinct constraints and motivations, which can result in conflicts over priorities and methods. For instance, while the central government might focus on national security, local governments may prioritise regional economic benefits, and NGOs might advocate for humanitarian concerns. These differing perspectives and objectives can create friction, impacting the coherence of border infrastructure development.

As an institutional response to cross-border migration, border infrastructures initiate cumulative effects that progressively reinforce and amplify the impacts of initial changes over time (Durand and Massey 2019). When states implement stricter border controls or more effective infrastructure, such as increased surveillance, these actions will trigger a chain reaction (Sadowski 2020; Hoffman Pham and Komiyama 2024). Stricter controls may drive the development of more sophisticated smuggling networks, prompting further security measures and creating a feedback loop that intensifies border enforcement (Punzo and Scaglione 2024). On the other hand, market-driven infrastructure may prioritise efficiency, profitability, and the seamless flow of goods and services, often resulting in investments that enhance economic growth and competitiveness. Over time, these responses can entrench new norms and practices, alter local economies, influence public opinion, and reshape international relations. The cumulative nature of these effects means that initial policy decisions or infrastructure projects can significantly reshape the landscape of migration, leading to complex and often unintended long-term consequences.

Institutional logics behind border infrastructures and shifts in logic

Institutional logics are the frameworks of beliefs, practices, and rules that guide behaviour and decision-making within institutions (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury 2012). These logics are deeply embedded in societal structures, shaping how individuals and organisations act by providing norms and values that dictate what is considered appropriate or legitimate. Although individuals and organisations may have agency in navigating the confines of institutions, the logics of institution still hold great power. This is because institutions are woven into the social fabric, which allows them to demand adherence and reinforces their influence over time. This deep integration allows institutional logics to persist even amid changes.

However, institutional logics are not static (Bitektine and Song 2023). They evolve along with shifts in social values, norms, and power structures. This evolution is driven by major societal transformations, such as technological advances, cultural shifts, or economic crises, or by political upheavals, external pressures, or shifts in power among key actors that challenge existing logics and open the door for new ones to emerge. As these societal changes unfold, the logics that once dominated a particular field may be reinterpreted, adapted, or even replaced by alternative logics that align more closely with the changed context, leading to the emergence of entirely new institutional logics or the transformation of existing ones.

The concept of institutional logic is essential for understanding how various actors, such as individuals, governments, and private firms, interact and influence one another. It offers valuable insights into the processes through which institutions evolve over time, as shifts in dominant logics drive substantial changes in policies, practices, and social outcomes. The impacts of the shifts extend beyond individual organisations to influence broader societal norms and expectations. As new logics take hold, they can redefine what is considered acceptable or desirable within a field, leading to the alteration of professional standards, regulatory frameworks, public perceptions, and priorities of entire sectors.

Since each institution has cumulative effects that reinforce its own logic, shifts in logic will not eliminate previous ones but will instead create a situation in which different logics coexist within a society. This situation further leads to competition and tensions as multiple logics vie for dominance, and their competition creates complex dynamics between institutions where actors must constantly navigate conflicting expectations and norms. As these logics interact, they can either conflict or converge, sometimes giving rise to hybrid practices that blend components of each logic, or fostering new forms of collaboration that address the demands of multiple logics simultaneously (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury 2012).

Amidst the significant tensions driven by the competition between logics, actors within a field may find themselves pulled in different directions by conflicting priorities. These tensions often result in instability or resistance to change, as organisations and individuals struggle to reconcile the demands of competing logics. This competition is particularly evident in the context of the evolution of border infrastructures, both physical and institutional. Initially, border infrastructures may have been designed mainly to facilitate trade and economic exchanges, reflecting a market-driven logic. However, as security concerns intensified, a shift towards a security-centric logic emerged, leading to the development of more restrictive and surveillance-oriented border infrastructures. The clash between these logics can create a complex environment in which economic and security priorities are in constant conflict. This ongoing tension can result in hybrid border infrastructures that attempt to balance these competing demands but lead to inefficiencies or unintended consequences, such as increased costs or delays in cross-border migration and trade. Moreover, as these infrastructures evolve, resistance to change becomes more pronounced, especially when entrenched interests or institutional inertia come into play. Therefore, border infrastructures will be subject to a constant state of renegotiation, as different logics continue to compete for dominance.

Analytical framework for analysing border infrastructure development in China’s southwest border

In the following analysis, we develop an analytical framework to trace the evolution of China’s border infrastructure development in its southwest border region over time. Our framework consists of four distinct stages: the early years of the People’s Republic of China (1950–1978), the early reform era (1979–1989), the high-growth era (1990–2012), and the security-centric transitional era (2013–present). We examine the roles of three main actors in these periods: the central government, the Ruili local government, and cross-border migrants, a diverse group that includes intermarriage spouses, border residents, traders, and migrant workers.

As we will demonstrate, during the first era, border infrastructure was minimal, reflecting the central government’s limited military presence, the Ruili government’s focus on civic responsibilities such as education and epidemic control, and the unregulated nature of cross-border migration. This period lacked a dominant actor and represented a natural, unstructured stage. In the second stage, both central and local governments began to play some roles, but their efforts were largely symbolic and lacked tangible impacts. A division of labour emerged: the Ruili government prioritised economic development, while Beijing focused on sovereignty and security. However, profit-seeking migrants, empowered by early market forces, were the primary drivers, who self-regulated and established the foundation for market-driven infrastructure. The third era marked an alignment of interests among the central government, Ruili government, and migrants. With Beijing’s regulatory and physical infrastructure support, Ruili played a pivotal role in fostering market and trade initiatives. This enabled immigrant communities and businesses to thrive as cross-border migration intensified. The Ruili government, as the main driver, oversaw these developments, balancing economic growth with regulatory oversight. In the current and fourth era, rising external security threats have prompted a significant shift to security concerns, leading to a divergence in institutional priorities. While Beijing emphasises tightened border control, Ruili remains focused on trade and economic affairs, shaped by its historical reliance on economic growth and geopolitical obligations. Despite this tension, cross-border migrants still enter Ruili, supported by long-established social and trade networks, which sustain the city’s unique and dynamic border governance.

Figure 1. The analytical framework for analysing border infrastructure development in China’s southwest border

| Early PRC years 1950–1978 | Early reform era 1979–1989 | High-growth era 1990–2012 | Transitional era 2013–present | |||

| Central government | Military presence in key sites only | Symbolic security infrastructures | Regulatory and physical infrastructures | Security-centric infrastructures | Multilevel governance | |

| Ruili government | No meaningful infrastructure building | Ineffective market driven infrastructures | Market and community infrastructures | Market-driven infrastructures | ||

| Cross-border migration | Laissez-faire preexisting migration | Infrastructure-developing migration | Stimulated and self- reinforcing migration | Resilient and self-sustaining migration | ||

| Minimal security infrastructures | Self-regulated infrastructures | Aligned developmental infrastructures | Transition to security- centric infrastructures | |||

Credit: the authors.

Ruili: A strategic gateway for cross-border migration and trade between China and Myanmar

Ruili, a border city in China’s southwestern Yunnan Province, holds a unique and strategic position along the China–Myanmar border. Situated on the banks of the Ruili River, which demarcates the boundary between the two state territories, Ruili has long been a crossroads of cultures and commerce. The city is part of the Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture, while the two most populous ethnic groups in the city, the Dai and the Jingpo, are also the majority in Myanmar’s adjacent Kachin and Shan States, respectively. This shared heritage means that a large number of border residents speak the same languages, practice the same religions, and maintain common cultural traditions, with extensive familial and clan ties across the border. As a result, it has been customary for residents on both sides of the border to cross frequently for various reasons, such as visiting family, seeking romance, celebrating festivals, doing business, or even enjoying a meal together.

Ruili’s proximity to Muse, the largest trading city on the Myanmar side, has established it as a key hub for bilateral trade. Since the beginning of China’s reform era, Ruili has experienced exponential growth in cross-border commerce, transforming into a vibrant economic centre. While the city’s trade was initially driven by jade and rare wood, it has since become the largest port for importing a wide range of agricultural products and exporting industrial goods such as electronics and motorbikes. The industrialisation of Ruili has accelerated as labour-intensive manufacturing sectors have relocated to the city, attracted by the availability of affordable Myanmar migrant labour. Today, Ruili is home to thousands of Myanmar manufacturing workers and hosts a significant number of Myanmar migrants hired across various service sectors, including restaurants, massage parlours, nail salons, housekeeping, sanitation, and construction, as well as agriculture, where they may work as sugarcane cutters or tea leaf pickers. The city’s economy is deeply intertwined with that of Myanmar, facilitating a substantial portion of the cross-border trade that sustains livelihoods on both sides of the border.

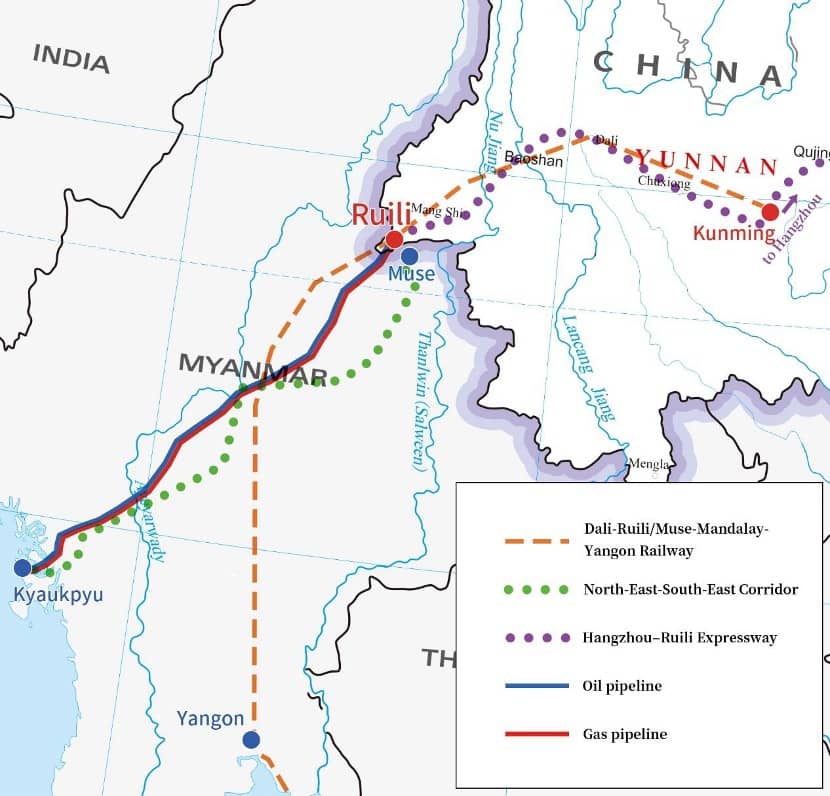

Figure 2. Map of Ruili in China’s infrastructural strategy

Credit: Birun Zou.

Data collection

Between November 2022 and February 2023, our research team, consisting of 6 professors and 20 college students from six universities, conducted fieldwork in Ruili to collect data on cross-border trade, migration, and social dynamics. Four members fluent in Burmese facilitated communication with local communities and stakeholders on both sides of the China–Myanmar border. The authors, both of whom are members of the team, later visited Ruili 11 times, with stays ranging from five days to one and a half months. Nine research members lived in Ruili for extended periods to engage with the socioeconomic and cultural landscape. Six of the members were embedded in six border villages, working as village committee assistants or social workers, who provided direct support while conducting research. Another one lived in a Myanmar immigrant community for several months for thorough observations and interactions with migrant populations. One member worked as an administrative intern at the national-level industrial park, gaining insights into cross-border labour migration management, while the last one was employed by a livestream e-commerce firm in the jadeite trade, offering a perspective on the digital economy’s role in cross-border commerce.

Figure 3. Consultative meeting on cross-border economic integration between our research team and the Ruili government

Credit: Tianlong You, August 2023.

Throughout the fieldwork, the authors conducted interviews with 121 individuals, including leaders from the Myanmar Jewellery Traders’ Association (Mianji zhubao shanghui 緬籍珠寶商會, the Association) and the Ruili Jewellery Association (Ruili shi baoyushi xiehui 瑞麗市寶玉石協會), who shared valuable insights into the jade and jewellery trade. We also interviewed officials from nearly 30 government authorities to identify regulatory and administrative challenges, and representatives from the Administration Committee of the National-level Border Industrial Park (Ruili shi guojia ji yanbian chanyeyuan guanweihui 瑞麗市國家級沿邊產業園管委會), who provided us with detailed information on infrastructure and economic development. This multi-faceted approach has generated rich data, which enhances our understanding of Ruili’s strategic role in China–Myanmar border interactions.

1949–1978: Minimal border infrastructure and preexisting cross-border migration

In the early decades of the People’s Republic, China’s southwest border faced security challenges stemming from neighbouring countries. These included the spillover effects of the Vietnam War, the China–India War of 1962, and the Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979, as well as civil wars and anti-Chinese movements in Myanmar. However, due to its limited state capacity, the central government was able to develop only minimal infrastructure, primarily for military purposes, while local governments in these areas, impoverished and lacking resources, were unable to develop any form of infrastructure independently. At the same time, compounding these challenges, all of China was embroiled in successive political movements that diverted attention away from economic development. As a result, with a security-centric institutional logic in place and minimal border infrastructure, cross-border migration, while historically present, remained stable. Besides sporadic movements triggered by extreme circumstances, there were no significant factors driving its expansion during this period.

When the People’s Republic of China was established, the new government lacked the resources to provide comprehensive military protection, especially as China saw itself as being contained by the United States and its allies. Additionally, northern Myanmar, which had been controlled by Myanmar’s ethnic armed forces, had become a refuge for remnants of Kuomintang military forces, which posed a threat to the border areas of Yunnan (Ngeow 2023). Given these challenges, the founding leaders of the new republic saw newly independent Myanmar as a potential ally in the international community, crucial for breaking the Western containment strategy. In the spirit of fostering this relationship, China decided to make significant concessions during border demarcation discussions, aiming to set a positive example for future border negotiations with other neighbouring countries (Bert 1975). Ultimately, China prioritised securing territories of greater military strategic importance and deployed its forces to defend key sites, while ceding the vast majority of the disputed areas to Myanmar. This security-centric logic to border infrastructure was further reinforced as China engaged in a series of conflicts with neighbouring states.

During this period, Ruili was socioeconomically underdeveloped. In 1951, Ruili had 5,180 households with a population of 28,751, of which only 1% were Han Chinese and who were mostly government officials, state-owned farm workers, and military personnel from elsewhere.[2] In 1950, Ruili had only one elementary school in the basin area, serving just 30 pupils with one tutor, and three church schools in the mountain areas. Before 1950, Ruili was notorious for widespread epidemics, with more than 40% of the population infected with malaria. According to municipal records,[3] Ruili was transitioning from “a primitive communal economy to a landlord economy in the basin areas, while the mountain areas remained in the final stages of a primitive society.”[4] Due to the hyper-ideological political movements of the 1950s, which prioritised class conflicts over economic growth, the local government’s focus was primarily on civic responsibilities such as compulsory education, public health, and ethnic solidarity. A local resident in his eighties from Ruili described to us the socioeconomic struggles the city faced in the past:

Unlike today, before the 1990s, Ruili was much poorer than Muse. When people from Myanmar came over, they brought goods we couldn’t produce ourselves. Ninety percent of the items in our marketplace were supplied by Myanmar traders. Back then, we were the ones who were looked down upon, and our girls were eager to marry Myanmar husbands. (Interview, 19 January 2023)

As the frontier of the ideologically-driven foreign policy of the PRC’s early years, Myanmar, whose relationships with China deteriorated in the 1960s, was viewed as a repressive capitalist regime to be overthrown by the communist forces of Burma, aided by China and staffed by youths from southwest China, including Ruili. Diverted from economic growth by various political and ideological tasks, Ruili lacked the resources to develop either physical or institutional border infrastructure. A Chinese local who moved to Myanmar with his family during this period explained their decision to leave:

The government was preoccupied with struggle sessions or mobilising youth to join international communist movements in Myanmar. Many of us who didn’t want to be involved simply moved to Myanmar, and the authorities couldn’t do anything about it. Most of my family members still live there, just miles away. (Interview, 4 February 2023)

Despite China’s stringent control over the status, residence, and everyday activities of foreigners, its southwest border had been a notable exception. For centuries, China shared border regions with its neighbours, until they turned into nation-states after World War II. Limited by state capacity, the newly found Chinese government had to leave the border with Myanmar largely open and unregulated. At the same time, since this region abutted areas controlled by Myanmar’s various ethnic armed forces, the central government of Myanmar could not effectively exercise migration control there either. As a result, people living in the border area shared deep and extensive familial, ethnic, and religious ties that could not be simply severed by the newly drawn but usually unguarded borders (Dean 2005; Sturgeon 2012). Despite holding different citizenship, border residents remained closely connected, with little awareness of border-crossing, as the presence and authorities of both states were largely invisible in this region. A senior who lives in a border village jointly owned by both countries told us:

We didn’t realise we had become citizens of different countries when they drew the borders. To us, we were still the same people, still countrymen and women. We were family, with some of us living on the Myanmar side and others in China. We visited each other frequently in the old times, often just by walking across farmland or crossing a river, and suddenly we found ourselves in another country’s territory. (Interview, 5 August 2023)

Consequently, cross-border migration in this area often occurred with little regulation. During times of peace, cross-border activities such as peddling, temporary agricultural work, and intermarriage continued unabated. The complex local and geopolitical situation further contributed to frequent cross-border movement, often driven by the need for refuge, a form of shock mobility. For example, in the 1950s and 1960s, many Ruili residents moved to Myanmar to escape political movements that were perceived as unfairly infringing on their rights. Many Jingpo villagers joined their co-ethnics in Myanmar’s nearby Kachin State for religious purposes, while other residents, including Han Chinese, sought food and security in Myanmar during the famine years. Meanwhile, the armed conflicts that erupted in Myanmar from the moment of its founding affected all of its border states adjacent to China and turned Ruili and other border cities into refuges for those fleeing the violence. Many displaced individuals found temporary shelter in the homes of family members and friends across the border in China, seeking safety from the turmoil in Myanmar.

1978–1989: Early attempts at building border infrastructure and self-regulated cross-border migration

In the early years of the reform era, China’s institutional logic shifted from hyper-ideological security concerns to a focus on economic development. In an effort to facilitate regulated economic growth, the central and local governments sought to both liberalise and control cross-border migration. However, due to China’s weak economic conditions in the early reform era, these governments were unable to establish the necessary border infrastructure to manage cross-border migration and the expanding trade that resulted from increased economic activity.[5] The infrastructures created by the central government during this time were largely symbolic, intended to assert Chinese sovereignty over the region and demonstrate that efforts were made. At the same time, the infrastructures developed by Ruili were also considered unsuccessful attempts as all of China was rebuilding its market economy. As a result, cross-border migration, which had been self-reinforcing and expanding during this period, became increasingly self-regulated and closely tied to the burgeoning cross-border trade, with the symbolic presence of border infrastructure playing a supportive but limited role.

Starting in the late 1970s, the central government shifted away from strict migration controls and embraced open-door policies to streamline the management of foreigners across most of the country. These policies were part of a broader strategy to open China to the world, attract foreign investment, and stimulate economic growth. However, in the border areas, particularly along the Myanmar–China border where migration control had historically been lax, the implementation of these policies took on a different shape. The focus became one of systematically channelling and formalising cross-border migration through key points such as Ruili in a manner that was more symbolic than substantive. A border checkpoint staffed by a small number of border patrol officers was established in Ruili for the first time in March 1978, as a tired official recalled. This move was intended to signal China’s sovereignty and its intention to manage the increasingly complex flows of people and goods across its borders. However, the patrol’s capacity was limited, particularly given the extensive and porous nature of the Myanmar–China border. The border patrol could only respond to calls for supervision in areas that were reportedly heavily trafficked, leaving vast stretches of the border largely unattended. This limited presence meant that the checkpoint and other border infrastructure were more about creating an appearance of control than actually altering the dynamics on the ground in practice (Zhang 2019).

The Ruili government sought to capitalise on the rapidly expanding cross-border trade by establishing its own infrastructure to support this burgeoning activity. They created several state-owned trade companies to export goods such as bicycles, soap, and other everyday items to Myanmar traders, who in turn brought garments and jadeite products into China. However, the substantial profits from cross-border trade quickly undermined the government’s efforts. Many seasoned traders said that many employees of these state-owned companies began bypassing customs inspections and channelling raw jadeite stones and products into the black market. As China’s economy increasingly liberalised, these state-owned trade firms were swiftly marginalised. To further facilitate the booming trade and gain a better understanding of the scale of commerce and migration, the Ruili government issued local border passes that allowed traders to work and reside in Ruili for short periods. Although these passes offered a practical means for managing and encouraging cross-border activity, they had no legal standing since immigration matters fell under central jurisdiction. Essentially, the Ruili government issued unauthorised documents that served as only symbolic gestures, offering a placebo effect to migrants who were unaware of their lack of legal validity. Although these efforts were largely symbolic and often ineffective, the Ruili government gradually became a local developmental state with a strong focus on economic growth and increasingly sophisticated governance.

During this period, in addition to the existing forms of cross-border migration such as refuge-seeking and marriage, border residents explored new types of migration during the early reform era. Religious exchange became increasingly common, with Theravada temples in China seeking young monks from Myanmar, while Myanmar children crossed the border to receive proper education in Ruili. More importantly, the shift towards economic development across China created numerous new opportunities for cross-border trade and economic activity. For example, since China lacked the capacity to produce clothes, many used jeans, jackets, and other types of garments from Western countries found their way into Ruili through Myanmar, meeting the growing demand of Chinese people for consumer goods. In addition, the consumption of jadeite products and rare wood furniture, items that were once perceived as symbols of feudalistic and capitalistic lifestyles and thus suppressed for decades, rapidly resumed through skyrocketing cross-border migration. This resurgence revitalised two billion-dollar sectors that soon became cornerstones of Ruili’s economy, further solidifying its role as a key hub for cross-border migration and trade. A very successful Chinese trader who lived through that period told us what happened:

In the past, Myanmar’s green mountains were rich with rare woods, like redwood. We would simply drive across the border with our tools, harvest the wood, and then return, avoiding customs by taking routes with no checkpoints. (Interview, 12 August 2024)

The contraband often included live animals such as cattle. A director of a border village confirmed this, saying:

Those people herded hundreds of cattle across the border through our village, and some were from our village, so we turned a blind eye as long as they contributed to the village. If they were caught, they would butcher the cattle and barbecue the beef on the other side of the border, then invite people to come, take the meat, and bring it home. (Interview, 25 January 2024)

The contraband marketplaces, which might have been expected to operate underground, instead thrived openly with well-known locations, established operating times, and a network of participants, including buyers, sellers, and moneychangers. The emergence of this robust market economy both facilitated the expansion of these illicit activities and led to a transformation in cross-border migration, which began to regulate itself around the opportunities presented by the booming trade. As the market flourished, the flow of people across the border became more organised and predictable, driven by the economic incentives and self-enforced norms established within these thriving marketplaces. An experienced jadeite trader shared his memory with us:

We used to meet at the Evergreen Tree Hotel every morning between 10 and 12 o’clock. The moneychanger, often a member of a Chinese ethnic minority with family ties in Myanmar, would arrange the meeting and bring both parties to a nearby hotel room to conduct the transactions. During these negotiations, buyers could shake hands with the sellers at an agreed-upon price. Once the deal was made, there were no returns or refunds allowed. (Interview, 18 April 2024)

1990–2012: Developmental border infrastructures and stimulated cross-border migration

Soon enough, these initially symbolic initiatives evolved into more formalised and sophisticated strategies as the government gained experience and state capacity, leading to a structured and regulated approach to cross-border interactions. During China’s era of rapid economic growth from 1990 to 2012, the central and local governments took distinct yet complementary roles in developing border infrastructure. The central government focused on creating regulatory frameworks to drive economic growth, building physical infrastructure to facilitate efficient transport and migration, and elevating the diplomatic relations with Myanmar for geopolitical purposes. On the other hand, the Ruili government focused on market supervision, investment promotion, and community governance. Liberated with greater authority, Ruili took charge of infrastructure building. This concerted effort resulted in the creation of robust and comprehensive border infrastructures for economic growth, with governments aligning their interests towards this objective. These infrastructures supported a considerable increase in profit-seeking cross-border migration, paralleling the explosive growth in cross-border trade.[6]

After Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour in 1992, China reaffirmed its commitment to reform and opening and designated Ruili a hub for cross-border trade and migration as a priority for favourable policies. Through successful policy experiments, Ruili’s administrative level was elevated, and it was designated a national-level cross-border economic collaboration zone (guojia ji kuajing jingji hezuo qu 國家級跨境經濟合作區), a key development and opening-up experimental zone (zhongdian kaifa kaifang shiyan qu 重點開發開放試驗區), and a centrepiece of strategic initiatives such as the Bridgehead Strategy (qiaotoubao zhanlüe 橋頭堡戰略).[7] These initiatives solidified Ruili’s strategic importance in China’s efforts to expand its influence in South and Southeast Asia. The central government introduced major policies to elevate Ruili’s role as a regional gateway, including lifting travel restrictions for Myanmar traders entering inland Yunnan, issuing them with Border Resident Cards, implementing whitelist customs policies for Jiegao Port, and granting greater flexibility in managing Myanmar nationals. These regulatory reforms supported significant upgrades to Ruili’s physical border infrastructure. National strategies such as the Great Western Development (xibu da kaifa 西部大開發), Bridgehead Strategy, and Belt and Road Initiative further accelerated Ruili’s growth as a vital trade hub linking China to South and Southeast Asia. Infrastructure projects included extending the Kunming-Ruili Highway to major Chinese coastal cities, and constructing highways, railways, and pipelines connecting Ruili to key Myanmar ports such as Kyaukpyu under a 99-year lease to China. By the early 2000s, Jiegao border gates, a cross-border walkway, a cargo yard, and an inspection building were constructed to formalise border control and improve efficiency.

Building on national efforts to enhance cross-border trade and transport infrastructure, Ruili took a significant step by building a marketplace, mainly for jadeite trade, and increasingly, a broader economic base. In 1992, Ruili established its first jewellery marketplace. By confining sellers and buyers to a designated area under supervision, Ruili’s authorities could monitor transactions more effectively. Previously, Myanmar peddlers could cross borders and sell low-quality or fake jadeite products to ill-informed tourists, which undermined the entire sector. The new marketplace not only curbed these activities but also attracted more participants by offering a secure, well-regulated environment for trade. A former market supervisor remembered the urgency with which the improvement of Ruili’s market environment was undertaken at that time:

We set up quality inspection stations at the entrance of every marketplace to ensure the integrity of each jadeite product and to boost customer confidence in both the industry and Ruili. In collaboration with the police, prosecutors, and the courts, we took strong action against dishonest traders from both Myanmar and China. Even today, the big traders are grateful for our efforts in establishing and enforcing market supervision regulations, saying that we helped save the industry. (Interview, 8 August 2024)

The marketplace – at core a commercial infrastructure – served the additional function of immigration control by managing previously underregulated international migration centred around this trade within a controlled space. The establishment of the marketplace also significantly influenced the residential patterns of Myanmar people in Ruili. Initially, they stayed in hotels for short-term jadeite transactions, but high costs led them to seek cheaper accommodations in the spare rooms of local homes or to build shelters in courtyards. As the marketplace became central to their trade, a community, Old Burmese Street (lao Mian jie 老緬街), emerged, which attracted more Myanmar migrants and became a social hub. This area, along with other immigrant communities, saw the development of commercial, religious, and social networks. By the early 2010s, Ruili had three main Myanmar communities centred around government-sponsored mosques and temples, which further solidified these social infrastructures.

Capitalising on affordable Myanmar labour, Ruili successfully attracted numerous manufacturing companies from China’s coastal provinces to establish new factories in the area (Yang 2014). In a few years, Ruili’s labour-intensive industries experienced rapid growth, drawing hundreds of thousands of migrant workers from across Myanmar. With greater flexibility in policy experimentation regarding foreigner management, Ruili continued to refine its regulatory infrastructure based on practical experience. In 2013, coinciding with the early phase of the Belt and Road Initiative, Ruili announced the construction of a pioneering foreigner service centre and developed a comprehensive database for micromanaging foreigners, covering areas such as border entry, work authorisation, epidemic control, housing, and education. This one-stop service centre streamlined the process for newcomers to obtain all necessary documents for employment and settlement in Ruili. The city explored new policy areas, including cross-border medical services, transborder internet access, and government-sanctioned financial services to replace the traditional shadow banking system used by both Chinese and Myanmar residents.

Encouraged by the Ruili government, Myanmar traders took the initiative to apply for approval to establish the Myanmar Jewellery Traders’ Association, a migrant-led commercial and social infrastructure. Most Myanmar traders have participated in the Association, which provides essential support for business and settlement in Ruili. Recognising the Association’s extensive social network, the local government relied on it for managing issues such as missing persons, document processing, and business fraud. In addition, the Association assisted in locating fugitives who fled to Myanmar, verifying the backgrounds of new Myanmar migrants, and other services that the Chinese authorities were not able to provide. The vice president of the Association, a Myanmar trader of Chinese descent, explained to us what they did:

We can help [the Ruili police] find the ones they want immediately if they cannot. Doing business, you know, may go good or bad, which is common, so we need to help resolve disputes between Chinese and Myanmar people, giving them guidance like what parents do for the whole family. (Interview, 25 January 2024)

In return, Ruili allowed the Association to establish three Burmese-language schools, which addressed the needs of Myanmar migrant children and facilitated the settlement of an increasing number of Myanmar migrants in the city.

With the establishment of the marketplace, cross-border migration and trade in Ruili expanded rapidly. By 2018, although the local registered population was only 250,000, the city hosted more than 100,000 traders from other parts of China and more than 50,000 foreigners from neighbouring countries who resided in Ruili for extended periods. In 2018 and 2019, the total number of foreign nationals inspected at the Ruili Port ranked first nationwide.[8] This influx transformed Ruili into a thriving hub of economic and cultural exchange. Before Covid-19, Ruili’s demographic composition reflected its unique role as a regional gateway: among a total population of 500,000, one-third were locals, one-third came from other parts of China, and one-third were foreign nationals.[9] This diversity fuelled economic growth and created a vibrant cultural landscape. Foreign traders brought different languages, religions, customs, and business practices, enriching Ruili’s social fabric. The city’s infrastructure adapted to support this dynamic environment, with thriving markets and businesses catering to cross-border activities. Ruili thus became a microcosm of China’s ambitions in regional integration and global economic engagement.

2013–present: The resilience of cross-border migration amid the transition to a security-centric logic and the tensions between different infrastructural logics

In this era of intensified geopolitical competition, unstable political conditions in neighbouring countries, and the Covid-19 pandemic, China has increasingly stressed national security and integrated it into infrastructure maintenance and development. As a consequence, the central government has gradually shifted the institutional logic of existing infrastructures from market-driven to security-centric and has established new border infrastructure focused solely on security. Meanwhile, the Ruili government remains mainly responsible for economic development and continues to build market-driven infrastructure. However, with the growth of Ruili’s role in developing security-centric infrastructures established by the central government, the cumulative effects of decades of market-driven policies create challenges for Ruili in reorienting priorities, leading to conflicts between institutional logics. Despite tighter management, however, Myanmar migrants still can find their ways into Ruili and other parts of China, which demonstrates their resilience in such challenging circumstances.

After China became the world’s second-largest economy in 2010, the United States initiated its “Pivot to Asia” strategy, later expanding to the Indo-Pacific, to counter China’s growing influence, especially through its Belt and Road Initiative. This has led to rising US-China tensions, including a prolonged trade war since 2018. Simultaneously, Southeast Asia has faced significant instability, with Myanmar’s 2021 military coup, Thailand’s political turmoil, and sporadic conflicts in Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia leading to regional insecurity. The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated China’s shift from market-driven to security-centric policies, especially in border areas such as Ruili, where heightened concerns over cross-border movement and imported cases led to extreme security measures. The National Immigration Administration, now a central civil authority, was granted expanded powers, including the establishment in Ruili of one of only six deportation centres. The construction of triple-layered walls, stretching a total of 600 kilometers in length, along Ruili’s 168-kilometer border, have severely restricted cross-border movement, significantly disrupting the informal trade crucial to local economies. Existing infrastructure, including the inspection station, can serve the purpose of migration restriction for security reasons, rather than migration facilitation. This broader shift towards stringent border control and national security in response to escalating geopolitical tensions and regional instability eventually threatens the economic survival of border communities dependent on cross-border exchanges.

Despite a heightened focus on security, Ruili remains a key player in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, especially as a gateway for the China–Myanmar Economic Corridor. Ruili is central to several multi-billion-dollar projects aimed at enhancing connectivity and economic integration between the two nations. To capitalise on its Myanmar labour, the city has actively sought economic growth by attracting light industries from major manufacturing hubs such as Quanzhou, Suzhou, and Ningbo in East China.[10] Moreover, Ruili has worked to modernise its jadeite industry, traditionally dominated by Myanmar traders, by partnering with Alibaba to transform it into an e-commerce powerhouse. Prior to the pandemic, Ruili, designated as one of only three free trade zones in Yunnan Province, introduced the “Pauk Phaw” card, indicating brotherhood in Burmese, which granted Myanmar migrants rights and privileges close to those of Chinese citizens (i.e., extended stays, legal work authorisation, and related permissions), although this policy was later suspended during the pandemic. Ruili’s market-driven logic nevertheless often clashes with the security-centric policies of the central government, leading to escalated central-local tensions, in particular in customs regulation and immigration control. The pandemic exacerbated these conflicts, with Ruili struggling to balance expanding security demands from above with its own goals of regional economic integration and trade promotion. As a result, the Ruili government’s market-driven infrastructure has become subordinate and complementary to the central government’s security-focused infrastructure.

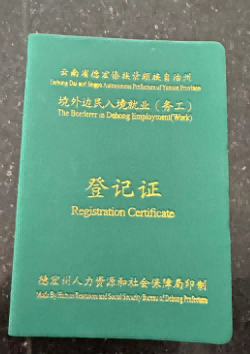

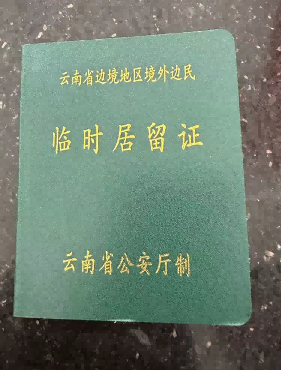

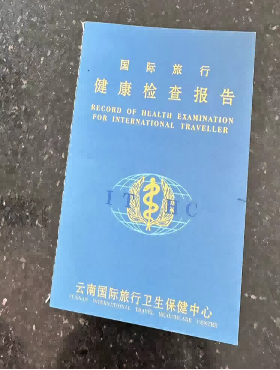

Figure 4. Various certificates issued to Myanmar migrants who work in China

Credit: Tianlong You.

Credit: Tianlong You.

Note: the photo on the left represents work authorisation, the one in the middle is a temporary residence documentation, and the one on the right displays a health check certificate.

Under dire circumstances, cross-border migration remains resilient in Ruili. First, Myanmar migrants who were not deported during the pandemic formed a more cohesive community in Ruili, governed by the Association following China’s grid management system. The Association assisted migrants with applying for various legal documentation for crossing the border between the two countries, or for temporary residency in China. In some cases, they have facilitated deportation in collaboration with the National Immigration Administration and have subsequently assisted the deportees with their documented return. Second, market-driven infrastructure, although under the watch of the National Immigration Administration, remains effective in recruiting Myanmar migrants for various local economic sectors, such as the manufacturing sector, the service sector, and the agriculture sector. Although recruitment has been affected by ever-changing circumstances as the result of China’s migration enforcement and Myanmar’s domestic unrest, and the number of Myanmar migrants is much lower than prior to the pandemic, market-driven infrastructure has been reviving Ruili’s economy. Third, the wall, the checkpoint, etc., forming the core of the security infrastructure are no longer maintained in a way that allows for their smooth functioning as China’s economy struggles with sharp decline since the end of the pandemic control, leading to less fiscal income. As China has been eager to reopen itself to the world after its nationwide lockdown for three years, it would be difficult to justify continuing investment in border walls that serve the opposite purpose. Thus, a number of Myanmar migrants have crossed the border walls into Ruili, and increasingly into other parts of China, through more weakly-guarded stretches. Fourth, after another civil war erupted in Myanmar in October 2023, Ruili suddenly faced a surge in the population of shelter-seeking Myanmar people, whom the local and central authorities were not allowed to turn away for humanitarian reasons.

Conclusion

Border infrastructures are not built in a day. They represent the culmination of decades of strategic planning, negotiation, and interaction between a diverse array of actors across multiple levels of governance. These infrastructures are shaped by both public and private sector initiatives, reflecting the priorities and influences of various stakeholders, including central and local governments, nongovernmental organisations, private enterprises, and ordinary citizens.

This article explores the evolution of border infrastructure in Ruili through the interplay of competing institutional logics – security, market, and community – and their ties to cross-border migration. It argues that border infrastructure development is shaped by shifting and coexisting logics driven by interactions among central and local governments, migrants, and other private actors. These logics reflect distinct priorities: security-centric logic emphasises state sovereignty and border control; market logic prioritises economic development and trade facilitation; and community logic sustains migration flows through resilient familial, ethnic, and social networks. While the state plays a significant role in shaping infrastructure, cross-border networks demonstrate their ability to adapt and persist, revealing the limitations of state efforts to fully regulate mobility. By engaging with existing literature on infrastructure studies and borderland governance, this article contextualises Ruili’s development within broader processes of state-building, geopolitics, and regional connectivity. It further highlights how China’s southwest border differs from its northwest border, which has been shaped by distinct historical and security pressures. More largely, this article contributes to studies of infrastructure by showing how competing institutional logics shape infrastructure development over time. It also deepens our understanding of China’s border by revealing how infrastructure and human dynamics reflect broader national and geopolitical priorities while remaining deeply influenced by local and cross-border interactions.

Acknowledgements

This study is partly funded by the “China Rural Social Survey,” a key project in the newest round of the construction of “Double First-class University” of Yunnan University.

Manuscript received on 4 September 2024. Accepted on 17 December 2024.

References

ANDERSON, Bridget. 2019. “New Directions in Migration Studies: Towards Methodological De-nationalism.” Comparative Migration Studies 7(36). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0140-8

ANDERSON, James, and Liam O’DOWD. 1999. “Borders, Border Regions and Territoriality: Contradictory Meanings, Changing Significance.” Regional Studies 33(7): 593-604.

BACHE, Ian, and Matthew FLINDERS (eds.). 2015. Multi-level Governance: Essential Readings. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

BI, Jiayin. 2024. “Can Rural Areas in China be Revitalized by Digitalization? A Dual Perspective on Digital Infrastructure and Digital Finance.” Finance Research Letters 67(A). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105753

BEINE, Michel, Frédéric DOCQUIER, and Çaglar ÖZDEN. 2011. “Diasporas.” Journal of Development Economics 95(1): 30-41.

BERT, Wayne. 1975. “Chinese Relations with Burma and Indonesia.” Asian Survey 15(6): 473-87.

BITEKTINE, Alex, and Fei SONG. 2023. “On the Role of Institutional Logics in Legitimacy Evaluations: The Effects of Pricing and CSR Signals on Organizational Legitimacy.” Journal of Management 49(3): 1070-105.

BRETTELL, Caroline B., and James F. HOLLIFIELD (eds.). 2015. Migration Theory: Talking Across Disciplines. London: Routledge.

CZAIKA, Mathias, and Hein de HAAS. 2014. “The Globalization of Migration: Has the World Become More Migratory?” International Migration Review 48(2): 283-323.

de GENOVA, Nicholas. 2017. The Borders of “Europe”: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering. Durham: Duke University Press.

DEAN, Karin. 2005. “Spaces and Territorialities on the Sino-Burmese Boundary: China, Burma and the Kachin.” Political Geography 24(7): 808-30.

DEAN, Karin, Jasnea SARMA, and Alessandro RIPPA. 2024. “Infrastructures and B/ordering: How Chinese Projects are Ordering China–Myanmar Border Spaces.” Territory, Politics, Governance 12(8): 1177-98.

DURAND, Jorge, and Douglas S. MASSEY. 2019. “Debacles at the Border: Five Decades of Fact-free Immigration Policy.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 684(1): 6-20.

FAIST, Thomas. 2000. The Volume and Dynamics of International Migration and Transnational Social Spaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

FLYVBJERG, Bent. 2014. “What You Should Know about Megaprojects and Why: An Overview.” Project Management Journal 45(2): 6-19.

GAMMELTOFT-HANSEN, Thomas, and Ninna Nyberg SØRENSEN (eds.). 2017. The Migration Industry and the Commercialization of International Migration. London: Routledge.

GERLAK, Andrea K., and Farhad MUKHTAROV. 2016. “Many Faces of Security: Discursive Framing in Cross-border Natural Resource Governance in the Mekong River Commission.” Globalizations 13(6): 719-40.

GIBSON, John, and David McKENZIE. 2014. “The Development Impact of a Best Practice Seasonal Worker Policy.” Review of Economics and Statistics 96(2): 229-43.

HANSON, Gordon H. 2009. “The Economic Consequences of the International Migration of Labor.” Annual Review of Economics 1: 179-208.

HOFFMANN PHAM, Katherine, and Junpei KOMIYAMA. 2024. “Strategic Choices of Migrants and Smugglers in the Central Mediterranean Sea.” PLOS ONE 19(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0300553

HOLLIFIELD, James F., and Tom K. WONG. 2014. “The Politics of International Migration: How Can We ‘Bring the State Back In’?” In Caroline B. BRETTELL, and James F. HOLLIFIELD (eds.), Migration Theory: Talking Across Disciplines. London: Routledge. 226-87.

JONES, Reece, and Corey JOHNSON. 2016. “Border Militarization and the Rearticulation of Sovereignty.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41(2): 187-200.

KONRAD, Victor. 2015. “Toward a Theory of Borders in Motion.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 30(1): 1-17.

LARKIN, Brian. 2013. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42(1): 327-43.

LAVENEX, Sandra, and Rahel KUNZ. 2020. “The Migration-development Nexus in EU External Relations.” Journal of European Integration 30(3): 439-57.

MAHONEY, James, and Kathleen THELEN. 2010. Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MASSEY, Douglas S., Joaquín ARANGO, Graeme HUGO, Ali KOUAOUCI, Adela PELLEGRINO, and J. Edward TAYLOR. 1993. “Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal.” Population and Development Review 19(3): 431-66.

——. 1998. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MASSEY, Douglas S., Jorge DURAND, and Nolan J. MALONE. 2002. Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Era of Economic Integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

MEZZADRA, Sandro, and Brett NEILSON. 2013. Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor. Durham: Duke University Press.

NGEOW, Chow Bing. 2023. “Dragon in the Golden Triangle: Military Operations of the People’s Liberation Army in Northern Burma, 1960-1961.” Cold War History 23(1): 61-82.

PLÜMMER, Franziska. 2022. “Contested Administrative Capacity in Border Management: China and the Greater Mekong Subregion.” China Information 36(3): 303-28.

PUNZO, Valentina, and Attilio SCAGLIONE. 2024. “Beyond Borders: Exploring the Impact of Italian Migration Control Policies on Mediterranean Smuggling Dynamics and Migrant Journeys.” Trends in Organized Crime. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-024-09533-5

SADOWSKI, Jathan. 2020. “The Internet of Landlords: Digital Platforms and New Mechanisms of Surveillance and Control.” Surveillance & Society 52(2): 562-80.

STAR, Susan Leigh. 1999. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioural Scientist 43(3): 377-91.

STURGEON, Janet. 2012. Border Landscapes: The Politics of Akha Land Use in China and Thailand. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

SUGA, Nobuhito, Makoto TAWADA, and Akihiko YANASE. 2023. “Public Infrastructure Strategically Supplied by Governments and Trade in a Ricardian Economy.” Foreign Trade Review 58(1): 68-99.

THORNTON, Patricia H., William OCASIO, and Michael LOUNSBURY. 2012. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure, and Process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

WEIJNEN, Margot P. C., and Aad CORRELJÉ. 2021. “Rethinking Infrastructure as the Fabric of a Changing Society.” In Margot P. C. WEIJNEN, Zofia LUKSZO, and Samira FARAHANI (eds.), Shaping an Inclusive Energy Transition. Cham: Springer. 15-54.

XIANG, Biao, and Johan LINDQUIST. 2014. “Migration Infrastructure.” International Migration Review 48(1): 122-48.

YANG, Chun. 2014. “Market Rebalancing of Global Production Networks in the Post-Washington Consensus Globalizing Era: Transformation of Export-oriented Development in China.” Review of International Political Economy 21(1): 130-56.

YOU, Tianlong, and Mary ROMERO. 2022. “China’s Borderlands in the Post-globalization Era.” China Information 36(3): 337-45.

ZHANG, Juan. 2019. “Permissive Politics and Entrepreneurial Transgression in a Chinese Border Town.” Sojourn 33(3): 576-601.

[1] National Bureau of Statistics of China, “Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census [1] (No. 8). Residents from Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan and Foreigners Registered for the Census,” 11 May 2021, https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202105/t20210510_1817193.html (accessed on 2 September 2024).

[2] Ruili City Local Chronicles Compilation Committee 瑞麗市地方誌編纂委員會, 1996, 瑞麗市誌 (Ruili shi zhi, Ruili city gazetteer), Chengdu: Sichuan cishu chubanshe.

[3] Ruili City Local Chronicles Compilation Committee of Yunnan Province 雲南省瑞麗市地方誌編纂委員會, 2012, 瑞麗市志 (1978-2005), (Ruili shi zhi, The history of Ruili City (1978-2005)), Kunming: Yunnan renmin chubanshe.

[4] China’s official stance, rooted in Marxist and Engelsian principles, emphasised modernising border regions through revolution and social transformation to achieve integration. This reflected the government’s commitment to addressing underdevelopment and promoting socioeconomic progress through targeted policies.

[5] Kunming Customs District 中華人民共和國昆明海關, “口岸開放熱潮湧” (Kou’an kaifang rechao yong, Port opening boom surges), 14 August 2019, http://nanjing.customs.gov.cn/kunming_customs/611304/611306/ 2589182/index.html (accessed on 19 December 2024).

Liu Xiangyuan 劉祥元 and Zhang Zeyun 張澤雲, “瑞麗試驗區駛入‘快車道’” (Ruili shiyan qu shiru “kuai chedao,” Ruili Pilot Zone enters the “fast lane”), People’s Daily Overseas Edition (人民日報海外版), 17 December 2013, http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrbhwb/html/2013-12/17/content_1362817.htm (accessed on 20 December 2024).

[6] Kunming Customs District 中華人民共和國昆明海關, “瑞麗: 因開放而更美麗” (Ruili: Yin kaifang er geng meili, Ruili: More beautiful because of openness), 22 March 2019, http://shanghai.customs.gov.cn/kunming_ customs/611304/611307/2378516/index.html (accessed on 19 December 2024).

[7] The Bridgehead Strategy refers to a Chinese government initiative aimed at leveraging border regions, such as Yunnan Province, as strategic hubs for economic integration, trade expansion, and connectivity with neighbouring countries in Southeast Asia and South Asia. The term highlights the role of these regions as gateways for advancing China’s geopolitical and economic interests. However, the strategy was subsequently merged into the Belt and Road Initiative.

[8] Li Ji 李季 and Zhai Jinjun 翟晉均, “瑞麗累計報告新冠感染者41例, 其中緬甸籍26例” (Ruili leiji baogao xinguan ganranzhe 41 li, qizhong Miandian ji 26 li, Ruili reports a total of 41 Covid-19 cases, including 26 Myanmar nationals), The Paper (澎湃), 10 July 2021, https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_13526790 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

[9] Zhang Fan 張帆, Tang Weihong 唐維紅, Liu Yuanhong 劉元鴻, Xu Feng 徐鋒, Zhu Hongwei 祝鴻偉, Sun Boyang 孫博洋, Cao Min 曹旻, Cui Jingwen 崔競文, Zhu Hongyan 朱紅艷, and Xu Qian 徐前, “雲南瑞麗: 孔雀開屏彩蝶飛” (Yunnan Ruili: Kongque kai pingcai die fei, Yunnan Ruili: Peacock opens its tail and butterflies fly), People’s Daily Online (人民網), 27 October 2016, http://finance.people.com.cn/n1/2016/1027/ c1004-28811253-4.html (accessed on 19 December 2024).

[10] Ruili Municipal People’s Government 瑞麗市人民政府, “瑞麗召開招商引資工作推進會議強調: 提高站位用情用心抓好全年招商引資工作” (Ruili zhaokai zhaoshang yinzi gongzuo tuijin huiyi qiangdiao: Tigao zhanwei yong qing yong xin zhuahao quannian zhaoshang yinzi gongzuo, Ruili holds a promotion meeting on investment attraction work: Emphasising raising awareness and putting heart into year-round efforts), 23 October 2024, https://www.rl.gov.cn/Web/ _F0_0_5YQ13KCD8738B1EDA4814D16B7.htm (accessed on 19 December 2024).